BAKER ACT

BENCHGUIDE

November 2016

A Project of the Florida Court Education Council’s Publications Committee

Baker Act Benchguide September 2016

ii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The Publications Committee of the Florida Court Education Council acknowledges

and thanks Ms. Martha Lenderman, M.S.W., one of Florida’s recognized experts

on the Baker Act statute, and General Magistrate Sean Cadigan, Thirteenth Judicial

Circuit, for their diligent work on this Baker Act Benchguide. The materials in

Chapter Eight were created under the auspices of the Florida Department of Law

Enforcement.

This benchguide was partially extracted, with permission, from the “2014 Baker

Act User Reference Guide: The Florida Mental Health Act” written by Martha

Lenderman under a contract between USF Florida Mental Health Institute with the

Florida Department of Children and Families.

AUTHORS

Martha Lenderman, M.S.W., and General Magistrate Sean Cadigan, Thirteenth

Judicial Circuit

PURPOSE

The Baker Act Benchguide was developed to serve as an educational resource and

a user-friendly reference for Florida circuit judges who are dealing with

proceedings under the Baker Act. Although far-reaching, this benchook cannot

hope to be definitive; readers should always check cited legal authorities before

relying on them.

DISCLAIMER

Viewpoints reflected in this publication do not represent any official policy or

position of the Florida Supreme Court, the Office of the State Courts

Administrator, the Florida judicial conferences, the Florida Court Education

Council, or the Florida Court Education Council’s Publications Committee.

Baker Act Bench Guide November 2016

iii

FLORIDA COURT EDUCATION COUNCIL’S

PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE

The Honorable Angela Cowden, Tenth Circuit, Chair

The Honorable Cory Ciklin, Fourth District Court of Appeal

The Honorable Josephine Gagliardi, Lee County

The Honorable Ilona Holmes, Seventeenth Circuit

The Honorable Matt Lucas, Second District Court of Appeal

The Honorable Ashley B. Moody, Thirteenth Circuit

The Honorable Louis Schiff, Broward County

Ms. Gay Inskeep, Trial Court Administrator, Sixth Circuit

AUTHORS

Ms. Martha Lenderman, MSW

Pinellas County

Sean Cadigan, General Magistrate,

Thirteenth Circuit

PUBLICATIONS COMMITTEE STAFF

Ms. Madelon Horwich, Senior Attorney, Publications Unit,

Office of the State Courts Administrator

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

iv

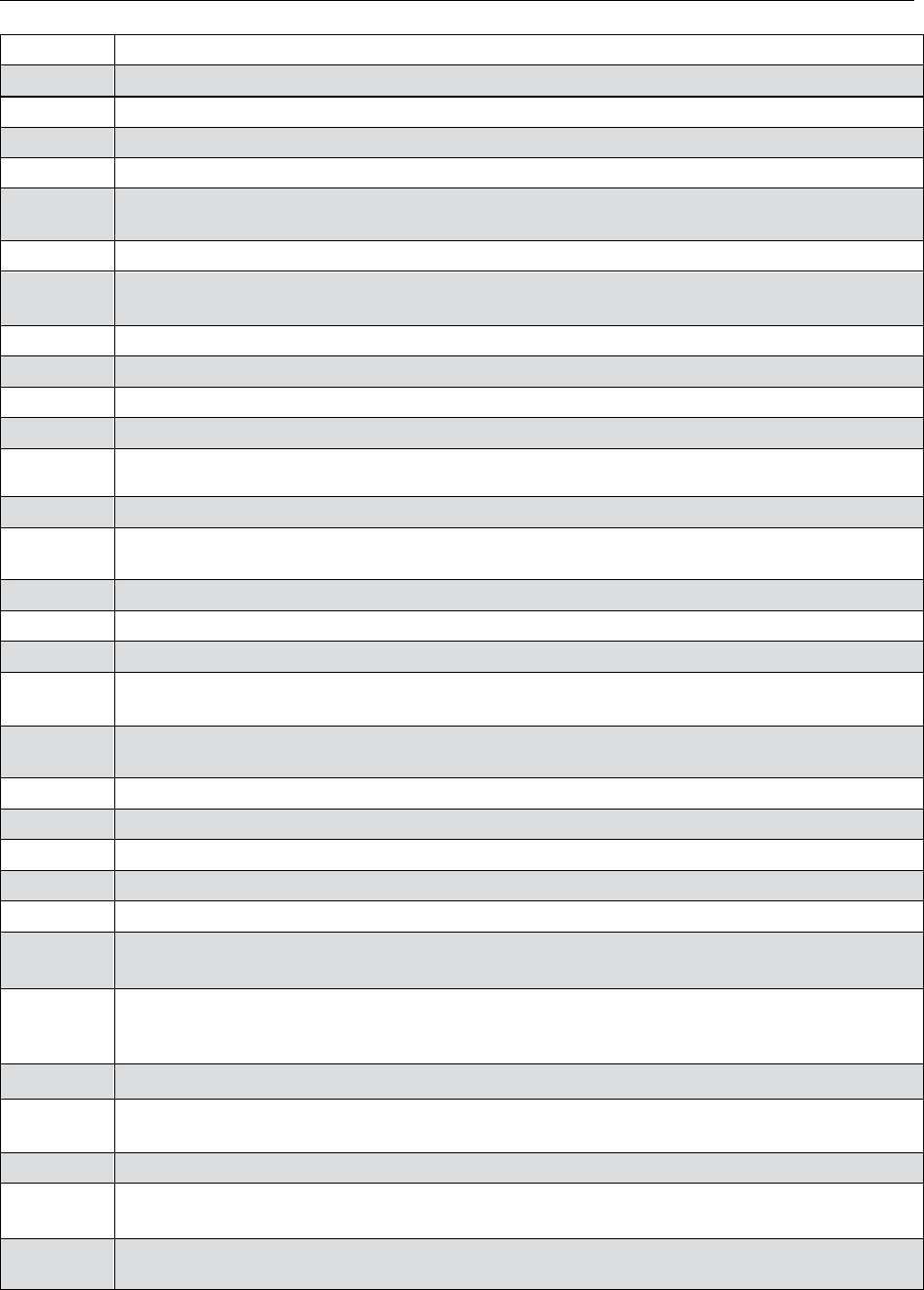

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Place your cursor over the item you would like to view and press

“Click” to go directly to that item.

Case law and most other legal citations are hyperlinked to the Westlaw database.

When you click on a link, you will be asked for your Westlaw sign-on information.

Once you are signed on, just minimize the screen. You should then be able to retrieve

all of the Westlaw hyperlinks you select. Due to technical difficulties, some legal

citations other than case law citations are linked to the primary sources.

Introduction: Development and Use of Baker Act Benchguide ................................. 1

Chapter One: History and Overview of Baker Act .................................................... 3

I. History ........................................................................................................... 3

II. Rights of Persons with Mental Illnesses ....................................................... 4

III. Voluntary Admissions ................................................................................... 6

A. In General .............................................................................................. 6

B. Selected Definitions .............................................................................. 6

C. Criteria for Voluntary Admissions ........................................................ 7

D. Voluntary Admission — Exclusions ..................................................... 7

E. Consent to Admission/Treatment .......................................................... 8

F. Transfer to Voluntary Status ................................................................. 8

G. Transfer to Involuntary Status ............................................................... 9

H. Discharge of Persons on Voluntary Status ............................................ 9

IV. Involuntary Examinations – § 394.463, Fla. Stat.; Fla. Admin. Code R.

65E-5.280 ....................................................................................................10

A. Criteria .................................................................................................10

B. Initiation of Involuntary Examination .................................................10

C. Definitions of Professionals ................................................................12

D. Selected Procedures for Involuntary Examinations ............................13

E. Initial Mandatory Examination ...........................................................14

F. Release from Involuntary Examination ..............................................14

G. Notice of Discharge or Release ...........................................................15

H. Reporting to DCF ................................................................................15

I. Transportation of Persons for Involuntary Examination .....................16

J. Persons with Criminal Charges ...........................................................18

K. Weapons Prohibited on Grounds of Hospital Providing Mental

Health Services ....................................................................................18

L. Paperwork Required by the Baker Act ................................................19

M. Involuntary Placement .........................................................................19

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

v

N. Continued Involuntary Services ..........................................................23

O. Discharge of Persons on Involuntary Status .......................................24

P. Transfers ..............................................................................................24

Q. Baker Act Oversight ............................................................................25

R. Immunity .............................................................................................25

S. Statute and Rule Matrix — Florida Mental Health Act

(Baker Act) ..........................................................................................27

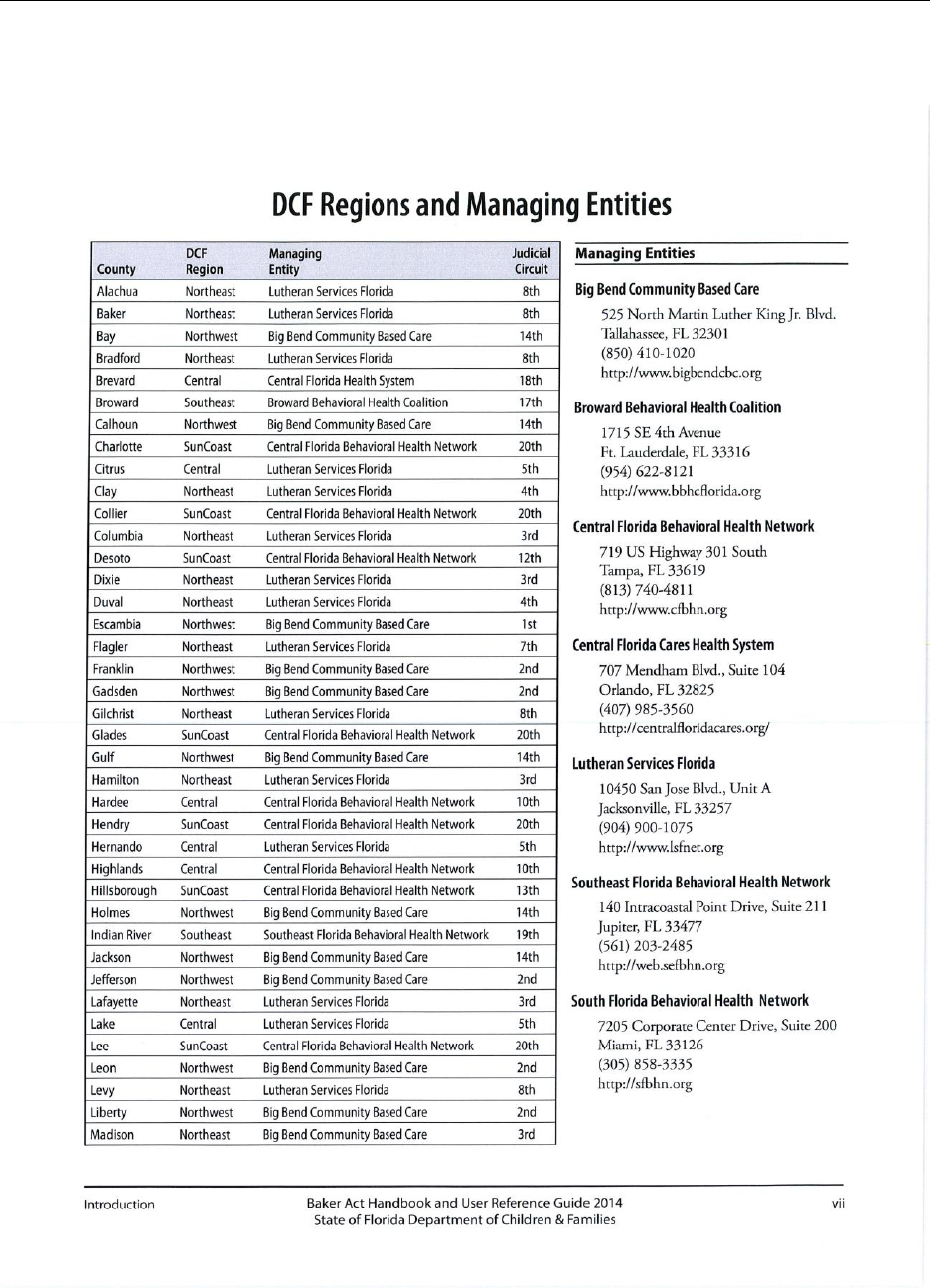

V. Maps of Administrative Entities Regions ...................................................30

A. Judicial Circuits and DCF Regions .....................................................30

B. DCF Regions and Managing Entities ..................................................31

C. Managing Entities................................................................................32

VI. Psychiatric Diagnoses and Treatment/Medication .....................................33

A. Diagnoses ............................................................................................33

B. Psychotherapeutic Medication ............................................................34

1. Generally ........................................................................................35

2. Antipsychotic Medications ............................................................36

3. Medications for Mood Disorders ...................................................38

4. Anti-Anxiety Medications ..............................................................41

C. Importance of Medication Compliance ...............................................41

D. Electroconvulsive Therapy (ECT) ......................................................42

VII. Adult Mental Health System of Services and Support ...............................43

VIII. Children’s Mental Health System of Services and Support .......................52

IX. Glossary of Common Definitions, Acronyms, and Abbreviations .............55

Chapter Two: Express and Informed Consent .........................................................63

I. Guardian Advocates and Other Substitute Decision Makers .....................63

II. Documentation of Competence to Provide Express and Informed

Consent ........................................................................................................64

III. Persons Determined Incompetent to Consent to Treatment .......................65

IV. Persons Adjudicated Incapacitated .............................................................66

V. Persons with Health Care Surrogates/Proxies ............................................67

VI. Summary of Consent Issues ........................................................................68

VII. Bench Card on Substitute Decision-Making ..............................................70

VIII. Frequently Asked Questions .......................................................................72

A. Competence to Consent .......................................................................72

B. Incompetence to Consent ....................................................................75

C. Disclosure ............................................................................................77

D. Consent to Treatment ..........................................................................78

E. Initiation of Psychiatric Treatment ......................................................80

F. Mental Health Advance Directives .....................................................81

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

vi

G. Electroconvulsive Therapy ..................................................................83

H. Consent to Medical Treatment ............................................................85

I. Guardian Advocates and Other Substitute Decision Makers ..............87

1. In General .......................................................................................87

2. Court-Appointed Guardians (Ch. 744, Fla. Stat.) ..........................88

3. Guardian Advocates .......................................................................92

4. Health Care Surrogates/Proxies ...................................................100

5. Powers of Attorney ......................................................................105

IX. Selected Model Baker Act Forms for Informed Consent and Use of

Substitute Decision Makers ......................................................................106

A. Petition for Adjudication of Incompetence to Consent to Treatment

and Appointment of a Guardian Advocate........................................107

B. Order Appointing Guardian Advocate ..............................................109

C. Petition Requesting Court Approval for Guardian Advocate to

Consent to Extraordinary Treatment .................................................110

D. Order Authorizing Guardian Advocate to Consent to Extraordinary

Treatment ...........................................................................................111

E. Authorization for Electroconvulsive Treatment................................112

F. Notification to Court of Person’s Competence to Consent to

Treatment and Discharge of Guardian Advocate ..............................113

G. Findings and Recommended Order Restoring Person’s

Competence to Consent to Treatment and Discharging the

Guardian Advocate ............................................................................114

Chapter Three: Admission and Treatment for Minors ..........................................115

I. Cautionary Note ........................................................................................115

II. Minority/Non-Age.....................................................................................115

A. Definition ...........................................................................................115

B. Removal of Disabilities of Non-Age .................................................116

C. Rights, Privileges, and Obligations of Persons 18 Years of Age

or Older ..............................................................................................117

D. Consent to Treatment ........................................................................117

III. Consent for Admission to a Mental Health Facility .................................119

A. Admission ..........................................................................................119

B. Hospitals ............................................................................................119

C. Children’s Crisis Stabilization Units .................................................120

IV. Consent to Psychiatric Treatment .............................................................121

A. Inpatient Treatment ...........................................................................121

B. Residential Treatment Centers ..........................................................121

C. Outpatient Crisis Intervention Services ............................................121

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

vii

V. Substance Abuse (Marchman Act) Admission and Treatment .................122

A. In General ..........................................................................................122

B. Criteria ...............................................................................................122

C. Initiation ............................................................................................123

D. Disposition .........................................................................................123

E. Parental Participation in Treatment ...................................................124

F. Release of Information ......................................................................124

G. Parental Participation/Payment .........................................................124

VI. Consent for General Medical Care and Treatment ...................................124

A. Power to Consent...............................................................................124

B. Emergency Care ................................................................................125

VII. Emergency Care of Youth in DCF or DJJ Custody ..................................126

VIII. Delinquent Youth ......................................................................................127

IX. Dependent Youth ......................................................................................128

A. Medical, Psychiatric, and Psychological Examination and

Treatment of Children in DCF Custody ............................................128

B. Psychotropic Medications for Children in DCF Custody .................130

C. Examination, Treatment, and Placement of Children in DCF

Custody ..............................................................................................134

X. Frequently Asked Questions .....................................................................135

A. Minority Defined ...............................................................................135

B. Informed Consent and Consent to Treatment ...................................136

C. Voluntary Admissions .......................................................................138

D. Involuntary Examinations .................................................................139

Chapter Four: Involuntary Examination ................................................................142

I. In General ..................................................................................................142

II. Criteria .......................................................................................................142

III. Initiation ....................................................................................................143

IV. Definitions of Mental Health Professionals ..............................................144

V. Initial Mandatory Involuntary Examination .............................................146

VI. Release ......................................................................................................146

VII. Notice of Discharge or Release .................................................................147

VIII. Involuntary Examination Flowchart .........................................................148

IX. Frequently Asked Questions .....................................................................150

A. Criteria and Eligibility .......................................................................150

B. Initiation in General...........................................................................156

C. Initiation by Courts ............................................................................158

D. Transport ...........................................................................................164

E. Examination and Release ..................................................................165

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

viii

X. Selected Baker Act Forms for Involuntary Examination..........................166

A. Petition and Affidavit Seeking Ex Parte Order Requiring

Involuntary Examination ...................................................................166

B. Ex Parte Order for Involuntary Examination ....................................171

Chapter Five: Involuntary Inpatient Placement .....................................................172

I. In General ..................................................................................................172

II. Criteria .......................................................................................................172

III. Initiation of Involuntary Inpatient Placement ...........................................173

IV. Petition for Involuntary Inpatient Placement ............................................173

V. Appointment of Counsel ...........................................................................173

VI. Continuance of Hearing ............................................................................174

VII. Independent Expert Examination ..............................................................174

VIII. Hearing on Involuntary Inpatient Placement ............................................174

IX. Admission to a State Treatment Facility ...................................................176

X. Release of Persons on Involuntary Status .................................................177

XI. Return of Persons ......................................................................................177

XII. Procedure for Continued Involuntary Inpatient Placement ......................178

XIII. Involuntary Inpatient Placement Flowchart ..............................................181

XIV. Continued Involuntary Inpatient Placement Flowchart ............................182

XV. Involuntary Inpatient Placement Hearing Colloquy .................................183

A. Introductory Remarks ........................................................................183

B. Preliminary Matters ...........................................................................185

C. Testimony and Evidence ...................................................................185

D. Closing Arguments ............................................................................188

E. Findings and Order of Court .............................................................188

1. Preliminary Contents ....................................................................188

2. When Baker Act Criteria Have Been Met ...................................189

3. When Baker Act Criteria Have Not Been Met ............................191

4. Sample Provisions for Short-Term Placement With

Reservation of Jurisdiction to Extend or Modify .........................191

XVI. Frequently Asked Questions .....................................................................192

A. Criteria and Eligibility .......................................................................192

B. Initiation and Filing of Involuntary Inpatient Placement ..................194

C. Public Defender and State Attorney ..................................................202

D. Independent Expert Examination ......................................................213

E. Continuances .....................................................................................214

F. Transfers for Medical Care ...............................................................216

G. Waiver of Hearings and Waiver of Patient Presence at Hearing ......216

H. Conversion between Voluntary and Involuntary Status ...................218

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

ix

I. Witnesses ...........................................................................................219

J. Hearings .............................................................................................222

K. Involuntary Placement Orders ...........................................................225

L. Continued Involuntary Inpatient Placement ......................................231

M. Baker Act Forms and Service of Process ..........................................232

N. Transfers of Persons under Involuntary Placement ..........................233

O. State Treatment Facilities and Transfer Evaluations ........................234

P. Convalescent Status ...........................................................................236

XVII. Selected Sample Baker Act Forms for Involuntary Inpatient

Placement ..................................................................................................238

A. Petition for Involuntary Inpatient Placement ....................................238

B. Notice of Petition for Involuntary Placement ...................................241

C. Application for Appointment of Independent Expert Examiner .......242

D. Notice to Court – Request for Continuance of Involuntary

Placement Hearing ............................................................................243

E. Order Requiring Involuntary Assessment and Stabilization for

Substance Abuse and for Baker Act Discharge of Person ................244

F. Order Requiring Evaluation For Involuntary Outpatient

Placement ..........................................................................................245

G. Notification to Court of Withdrawal of Petition for Hearing on

Involuntary Inpatient or Involuntary Outpatient Placement .............246

H. Order for Involuntary Inpatient Placement .......................................247

I. Petition Requesting Authorization for Continued Involuntary

Inpatient Placement ...........................................................................248

J. Notice of Petition for Continued Involuntary Inpatient

Placement ..........................................................................................250

K. Order for Continued Involuntary Inpatient Placement or for

Release ...............................................................................................251

Chapter Six: Involuntary Outpatient Services .......................................................252

I. Introduction ...............................................................................................252

II. Rights of Persons.......................................................................................252

III. Criteria .......................................................................................................252

IV. Petition ......................................................................................................254

V. Service Provider ........................................................................................255

VI. Treatment Plan ..........................................................................................256

VII. County of Filing ........................................................................................257

VIII. Notice of Petition ......................................................................................258

IX. Hearing ......................................................................................................259

X. Testimony ..................................................................................................260

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

x

XI. Court Order ...............................................................................................261

XII. Continued Involuntary Outpatient Services ..............................................261

A. Criteria ...............................................................................................261

B. Petition ...............................................................................................262

C. Notice of Petition for Continued Involuntary Outpatient

Services..............................................................................................262

D. Hearing on Continued Involuntary Outpatient Services ...................263

E. Order for Continued Involuntary Outpatient Services ......................264

XIII. Modification to Court Order for Involuntary Outpatient Services ...........264

XIV. Change of Service Provider ......................................................................265

XV. Noncompliance with Court Order .............................................................265

XVI. Discharge from Involuntary Outpatient Services .....................................267

XVII. Alternatives to Involuntary Outpatient Services Orders ...........................267

XVIII. Involuntary Outpatient Placement Flowchart

(DCF flowchart; 2016 legislative changes are not incorporated.) ............269

XIX. Continued Involuntary Outpatient Placement Flowchart .........................270

XX. Frequently Asked Questions .....................................................................271

XXI. Selected Model Baker Act Forms for Involuntary Outpatient

Services .....................................................................................................276

A. Petition for Involuntary Outpatient Placement .................................276

B. Designation of Service Provider for Involuntary Outpatient

Placement ..........................................................................................280

C. Proposed Individualized Treatment Plan for Involuntary Outpatient

Placement and Continued Involuntary Outpatient Placement ..........281

D. Order for Involuntary Outpatient Placement or Continued

Involuntary Outpatient Placement .....................................................284

E. Notice to Court of Modification to Treatment Plan for Involuntary

Outpatient Placement and/or Petition Requesting Approval of

Material Modifications to Plan ..........................................................286

F. Petition for Termination of Involuntary Outpatient Placement

Order ..................................................................................................287

G. Petition Requesting Authorization for Continued Outpatient

Placement ..........................................................................................288

H. Notice to Court of Waiver of Continued Involuntary Outpatient

Services Hearing and Request for an Order ......................................290

Chapter Seven: Rights of Persons with Mental Illnesses ......................................291

I. In General ..................................................................................................291

II. Frequently Asked Questions .....................................................................293

A. In General ..........................................................................................293

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

xi

B. Habeas Corpus ...................................................................................297

C. Clinical Records and Confidentiality ................................................299

D. Duty to Warn .....................................................................................307

E. Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) ...........................................308

F. Right to Dignity and Privacy .............................................................309

G. Communication Restrictions .............................................................310

H. Custody of Personal Possessions ......................................................312

I. Designated Representative ................................................................314

J. Right to Discharge .............................................................................315

K. Advance Directives ...........................................................................317

III. Forms .........................................................................................................320

A. Notice of Right to Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus or for

Redress of Grievances .......................................................................320

B. Petition for Writ of Habeas Corpus or for Redress of Grievances ...321

C. Advance Directive for Mental Health Care ......................................323

Chapter Eight: Firearm Prohibition for Certain Individuals With Mental

Illnesses .....................................................................................................330

I. Background ...............................................................................................330

II. Applicability of the Law ...........................................................................335

III. Responsibility of Various Entities to Implement Section 790.06,

Florida Statutes..........................................................................................336

A. Physicians Practicing at Baker Act Receiving or Treatment

Facilities ............................................................................................336

B. Baker Act Receiving Facility Administrators (or Designee) ............337

C. Clerks of Court ..................................................................................338

D. Judges or Magistrates ........................................................................339

E. Florida Department of Law Enforcement .........................................340

IV. Relief from a Firearm Disability ...............................................................341

V. Flowcharts .................................................................................................345

A. Admission by Voluntary Status.........................................................345

B. Admission by Involuntary Status ......................................................346

C. Firearm Prohibition Process ..............................................................347

D. Petition for Relief from Firearm Disability .......................................348

VI. Frequently Asked Questions .....................................................................349

A. Applicable State Statutes ...................................................................349

B. Mental Competency (MECOM) Database ........................................350

C. Substance Abuse ................................................................................353

D. Juveniles ............................................................................................354

E. Capacity/Competency .......................................................................355

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

xii

F. Relief from Disability ........................................................................355

G. Provisions of Chapter 2013-249, Laws of Florida ............................356

VII. Forms .........................................................................................................360

A. Firearm Prohibition Cover Sheet ......................................................361

B. Finding and Certification by an Examining Physician of Person’s

Imminent Dangerousness ..................................................................362

C. Patient’s Notice and Acknowledgment .............................................363

D. Application for Voluntary Admission of an Adult (Receiving

Facility)..............................................................................................364

E. Notification to Court of Withdrawal of Petition for Hearing on

Involuntary Inpatient or Involuntary Outpatient Placement .............365

F. Order of Court to Present Record of Finding to FDLE or

Requiring Further Documentation on Voluntary Transfer ...............366

G. Petition and Order for Relief from Firearm Disabilities Imposed

by Court .............................................................................................368

APPENDIX I: Recommendations from 1999 Report of the Supreme Court

Commission on Fairness, Subcommittee on Case Administration ...........371

APPENDIX II: Compendium of Appellate Cases, Attorney General Opinions, and

Other Legal References .............................................................................381

I. Evidence Supporting Criteria for Involuntary Inpatient Placement .........382

A. In General ..........................................................................................382

B. Outpatient Commitment ....................................................................388

C. Waiver of Patient’s Presence at Placement Hearing .........................392

D. Notice to and Participation of State Attorney at Involuntary

Placement Hearings ...........................................................................394

E. Duty of State Attorney and Role of Counsel for Receiving Facility

in Involuntary Placement Hearings ...................................................394

F. Deadline for Filing Petitions and Notices .........................................395

G. Appeal Not Moot ...............................................................................396

H. Jurisdiction of Courts ........................................................................397

I. Testimony ..........................................................................................397

II. Clinical Records and Confidentiality ........................................................398

III. Public Records ..........................................................................................403

IV. Payment of Involuntary Placement Bills ..................................................404

V. Transportation of Baker Act Patients ........................................................405

VI. Law Enforcement ......................................................................................408

A. Warrantless Entry — Exigent Circumstances ...................................408

B. Detention and Custody ......................................................................412

C. Use of Force ......................................................................................416

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

xiii

D. Weapons ............................................................................................417

VII. Responsibilities of and Lawsuits Against Doctors and Receiving

Facilities ....................................................................................................418

A. In General ..........................................................................................418

B. Duty to Warn .....................................................................................426

C. Malpractice vs. Ordinary Negligence ...............................................428

VIII. Guardianship and Protective Services ......................................................429

IX. Baker Act and Minors ...............................................................................431

X. Baker Act and Criminal Defendants .........................................................437

XI. Marchman Act ...........................................................................................442

APPENDIX III: List of FAQ Categories on DCF Website ...................................445

APPENDIX IV: List of All Mandatory and Recommended Baker Act Forms ....452

Introduction: Development and Use of Baker Act Benchguide

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

1

Introduction: Development and Use of Baker Act Benchguide

This benchguide is intended to help the courts appropriately carry out their

responsibilities related to the Baker Act, including:

To enter orders on ex parte petitions for involuntary examinations under the

Baker Act.

To conduct hearings on initial and continued involuntary inpatient placement

and involuntary outpatient services filed by administrators of Baker Act

receiving and treatment facilities.

To respond to petitions for writs of habeas corpus filed on behalf of

individuals held in Baker Act receiving or treatment facilities.

To respond to filings by Baker Act receiving facility administrators to limit

individuals’ access to firearm purchase or possession of a concealed weapon

permit.

This benchguide is intended to be used for informational purposes only. The

information presented herein is not legally binding and does not have any legal

authority. Only chapter 394, Florida Statutes, and chapter 65E-5, Florida

Administrative Code, as well as other federal and state laws, have legal authority.

The creation of administrative rules to implement and clarify the statute is

governed by chapter 120, Florida Statutes. The state law prohibits the repetition of

statute in administrative rules. Therefore, judges, magistrates, assistant state

attorneys, assistant public defenders, and clerks dealing with the Baker Act must

be familiar with and routinely reference both the statutes and the corresponding

rules to ensure correct implementation of the Baker Act law.

Please note that the forms and flowcharts included in this benchbook were

promulgated by DCF before the 2016 statutory amendments and do not incorporate

those changes.

To the extent possible, the word “individual” or “person” is used (rather than

“patient”) throughout this benchguide, except for direct quotes from the statutes

and for the purpose of clarity. Person-first language works to reduce stigma and

increases professional sensitivity to the dignity of persons served. Each chapter in

this benchbook contains useful material on select complex subjects derived from

Introduction: Development and Use of Baker Act Benchguide

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

2

the Baker Act law, administrative rules, forms, practices, and other statutes and

case law. A glossary of definitions, acronyms, and common terms is at the end of

Chapter One.

This benchguide was partially extracted from the “2014 Baker Act User Reference

Guide: The Florida Mental Health Act” written by Martha Lenderman under a

contract between USF Florida Mental Health Institute with the Florida Department

of Children and Families. The colloquy was prepared by General Magistrate Sean

Cadigan of the Thirteenth Judicial Circuit, who also reviewed the document for

usefulness to the judiciary.

The benchguide was otherwise prepared by Martha Lenderman. The material in

this benchguide was not prepared by attorneys, and reliance on its content should

not be considered as legal advice.

A separate benchguide for the Marchman Act governing substance abuse

impairment is in progress and will be available through the Office of the State

Courts Administrator.

Chapter One History and Overview of Baker Act

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

3

Chapter One: History and Overview of Baker Act

I. History

Statutes governing the treatment of mental illness in Florida date back to 1874.

Amendments to the law were passed many times over the years, but in 1971 the

Legislature enacted the Florida Mental Health Act. This Act brought about a

dramatic and comprehensive revision of Florida’s 97-year-old laws. It substantially

strengthened the due process and civil rights of persons in mental health facilities.

The Act, usually referred to as the “Baker Act,” was named after Maxine Baker,

the former State representative from Miami who sponsored the Act while serving

as chairperson of the House Committee on Mental Health. Referring to the

treatment of persons with mental illness before the passage of her bill,

Representative Baker stated: “In the name of mental health, we deprive them of

their most precious possession — liberty.”

Since the Baker Act became effective in 1972, a number of legislative amendments

have been enacted to protect persons’ civil and due process rights. The most recent

major revision was when Involuntary Outpatient Placement was added by the

Legislature effective January 2005. In 2016, three bills were passed that revised

mental health law in Florida. SB 12 was passed to improve access to court and

make the process more seamless for persons in crisis with substance abuse and

mental health issues. HB 439 authorizes the creation of mental health courts,

expands eligibility for veteran programs and courts, and HB 769 made changes,

such as reducing the period of time persons with certain nonviolent offenses may

be held in forensic facilities.

It is important that the Baker Act be used only in situations where the person has a

mental illness and meets all remaining criteria for voluntary or involuntary

admission. The Baker Act is the Florida Mental Health Act. It does not substitute

for any other law that may permit the provision of medical or substance abuse care

to persons who lack the capacity to request such care. For many persons, the use of

other statutes may be more appropriate. Alternatives to the Baker Act may include:

Developmental Disabilities, ch. 393, Fla. Stat.

Marchman Act (Substance Abuse Impairment), ch. 397, Fla. Stat.

Emergency Examination and Treatment of Incapacitated Persons, § 401.445,

Fla. Stat.

Federal Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA)

Chapter One History and Overview of Baker Act

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

4

hospital “Anti-Dumping” law, 42 U.S.C. § 1395dd.

Hospital Access to Emergency Services and Care, § 395.1041, Fla. Stat.

Adult Abuse, Neglect, and Exploitation, § 415.1051, Fla. Stat.

Health Care Advance Directives, ch. 765, Fla. Stat.

Guardianship, ch. 744, Fla. Stat.

Expedited Judicial Intervention Concerning Medical Treatment Procedures,

Fla. Prob. R. 5.900

II. Rights of Persons with Mental Illnesses

See § 394.459, Fla. Stat.; Fla. Admin. Code R. 65E-5.140. The Baker Act ensures

many rights to persons who have mental illnesses. Some of these rights are as

follows:

Individual Dignity: Ensures all constitutional rights and requires that

persons be treated in a humane way while being transported or treated for

mental illness.

Treatment: Prohibits the delay or denial of treatment due to a person’s

inability to pay, requires prompt physical examination after arrival, requires

treatment planning to involve the person, and requires that the least

restrictive appropriate available treatment be used based on the individual

needs of each person.

Express and Informed Consent: Encourages people to voluntarily apply

for mental health services when they are competent to do so, to choose their

own treatment, and to decide when they want to stop treatment. The law

requires that consent be voluntarily given in writing by a competent person

after sufficient explanation to enable the person to make well-reasoned,

willful, and knowing decisions without any coercion.

Quality of Treatment: Requires medical, vocational, social, educational,

and rehabilitative services suited to each person’s needs to be administered

skillfully, safely, and humanely. Use of restraint, seclusion, isolation,

emergency treatment orders, physical management techniques, and elevated

levels of supervision are regulated. Grievance procedures and complaint

resolution is required.

Communication, Abuse Reporting, and Visits: Guarantees persons in

mental health facilities the right to communicate freely and privately with

persons outside the facilities by phone, mail, or visitation. If communication

Chapter One History and Overview of Baker Act

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

5

is restricted, written notice must be provided. No restriction of calls to the

Abuse Registry or to the person’s attorney is permitted under any

circumstances.

Care and Custody of Personal Effects: Ensures that persons may keep

their own clothing and personal effects, unless they are removed for safety

or medical reasons. If they are removed, a witnessed inventory is required.

Voting in Public Elections: Guarantees individuals the right to register and

to vote in any elections for which they are qualified voters.

Habeas Corpus: Guarantees the right to ask the court to review the cause

and legality of the person’s detention or unjust denial of a legal right or

privilege or an authorized procedure.

Treatment and Discharge Planning: Guarantees the opportunity to

participate in treatment and discharge planning and to seek treatment from

the professional or agency of the person’s choice upon discharge.

Sexual Misconduct Prohibited: Provides that any staff who engages in

sexual activity with a person served by a receiving/treatment facility is guilty

of a felony. Failure to report such misconduct is a misdemeanor.

Right to a Representative: Ensures the right to a representative selected by

persons (or by facility when person can’t/won’t select their own) when

admitted on an involuntary basis or transferred from voluntary to

involuntary status. The representative must be promptly notified of the

person’s admission and all proceedings and restrictions of rights, receives

copy of the inventory of the person’s personal effects, has immediate access

to the person, and is authorized to file a petition for a writ of habeas corpus

on behalf of the person. The representative can’t make any treatment

decisions, can’t access or release the person’s clinical record without the

person’s consent, and can’t request the transfer of the person to another

facility.

Confidentiality: Ensures that all information about a person in a mental

health facility is maintained as confidential and released only with the

consent of the person or a legally authorized representative. However,

certain information may be released without consent to the person’s

attorney, in response to a court order (after a good cause hearing), after a

threat of harm to others, or in other very limited circumstances. Persons in

Chapter One History and Overview of Baker Act

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

6

mental health facilities have the right to access their clinical records.

Violation of Rights: Provides that anyone who violates or abuses any rights

or privileges of persons provided in the Baker Act is liable for damages as

determined by law.

III. Voluntary Admissions

A. In General

See § 394.4625, Fla. Stat.; Fla. Admin. Code R. 65E-5.270.

The Baker Act encourages the voluntary admission of persons for psychiatric care,

but only when they are able to understand the decision and its consequences and

are able to fully exercise their rights for themselves. When this is not possible due

to the severity of the person’s condition, the law requires that the person be

extended the due process rights assured for those under involuntary status.

B. Selected Definitions

See § 394.455, Fla. Stat.

Several definitions are important to understanding the criteria for voluntary

admissions and consent to treatment:

“‘Mental illness’ means an impairment of the mental or emotional processes

that exercise conscious control of one’s actions or of the ability to perceive

or understand reality, which impairment substantially interferes with a

person’s ability to meet the ordinary demands of living. For the purposes of

this part, the term does not include developmental disabilities as defined in

chapter 393, intoxication, or conditions manifested only by antisocial

behavior or substance abuse.” § 394.455(28), Fla. Stat.

“‘Express and informed consent’ means consent voluntarily given in writing,

by a competent person, after sufficient explanation and disclosure of the

subject matter involved to enable the person to make a knowing and willful

decision without any element of force, fraud, deceit, duress, or other form of

constraint or coercion.” § 394.455(15), Fla. Stat.

“‘Incompetent to consent to treatment’ means a state in which a person’s

judgment is so affected by a mental illness or a substance abuse impairment

that he or she lacks the capacity to make a well-reasoned, willful, and

Chapter One History and Overview of Baker Act

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

7

knowing decision concerning his or her medical, mental health, or substance

abuse treatment.” § 394.455(21), Fla. Stat.

C. Criteria for Voluntary Admissions

See § 394.459(3)(a).

Section 394.4625(1)(a), Florida Statutes, provides:

A facility may receive for observation, diagnosis, or treatment any

person 18 years of age or older making application by express and

informed consent for admission or any person age 17 or under for

whom such application is made by his or her legal guardian. If found

to show evidence of mental illness, to be competent to provide express

and informed consent, and to be suitable for treatment, such person 18

years of age or older may be admitted to the facility. A person age 17

or under can be admitted only after a hearing to verify the

voluntariness of the consent.

Each person entering a facility, regardless of age, must be asked to give

express and informed consent for admission and treatment. Express and

informed consent for admission and treatment of a person under 18 years of

age is required from the minor’s guardian. See Chapter Three of this

benchguide concerning who is a “guardian” of a minor.

D. Voluntary Admission — Exclusions

See § 394.4625(1), Fla. Stat.

A minor can be admitted on a voluntary basis only if willing and upon

application by his/her legal guardian and after a judicial hearing to verify the

voluntariness of the consent.

A facility may not admit a person on a voluntary basis who has been

adjudicated by a court as incapacitated.

The health care surrogate or proxy of a person on voluntary status may not

consent to mental health treatment for the person. Therefore, such a person

would be discharged from the facility or involuntary procedures initiated.

Certain individuals residing in or served by long-term facilities licensed

under chapters 400 and 429, Florida Statutes, may not be removed from their

Chapter One History and Overview of Baker Act

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

8

residence for voluntary examination unless previously screened by an

independent authorized professional and found to be able to provide express

and informed consent to treatment.

A person on voluntary status who is unwilling or unable to provide express

and informed consent to mental health treatment must either be discharged

or be transferred to involuntary status.

E. Consent to Admission/Treatment

Before consent to admission or treatment can be given, the following information

must be given to the person or his/her legally authorized substitute decision maker:

Reason for admission

Proposed treatment, including proposed psychotropic medications

Purpose of treatment

Alternative treatments

Specific dosage range for medications

Frequency and method of administration

Common risks, benefits, and common short-term and long-term side effects

Any contraindications that may exist

Clinically significant interactive effects with other medications

Similar information on alternative medication that may have less severe or

serious side effects

Potential effects of stopping treatment

Approximate length of care

How treatment will be monitored

Disclosure that any consent for treatment may be revoked orally or in

writing before or during the treatment period by any person legally

authorized to make health care decisions on behalf of the individual.

Within 24 hours after a voluntary admission of an adult, the admitting physician

must document in the person’s clinical record that the person is able to give

express and informed consent for admission and treatment. If the adult is not able

to give express and informed consent, the facility must either discharge the adult or

transfer the person to involuntary status.

F. Transfer to Voluntary Status

See § 394.4625(4), Fla. Stat.

Chapter One History and Overview of Baker Act

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

9

A person on involuntary status who applies to be transferred to voluntary status

must be transferred unless the person has been charged with a crime or has been

involuntarily placed for treatment by a court and continues to meet the criteria for

involuntary placement. Before the transfer to voluntary status is processed, the

mandatory initial involuntary examination must be performed by a physician,

clinical psychologist, or psychiatric nurse, and a certification of the person’s

competence to consent must be completed by a physician. In addition, the

competent person must have formally applied for voluntary admission.

G. Transfer to Involuntary Status

See § 394.4625(5), Fla. Stat.

At any time a person on voluntary status is determined not to have the capacity to

make well-reasoned, willful, and knowing decisions about mental health or

medical care, he/she must be transferred to involuntary status. When a person on

voluntary status, or an authorized individual acting on the person’s behalf, makes a

request for his/her discharge, the request for discharge, unless freely and

voluntarily rescinded, must be communicated to a physician, clinical psychologist,

or psychiatrist as quickly as possible, but not later than 12 hours after the request is

made. If the person meets the criteria for involuntary placement, the administrator

of the facility must file a petition for involuntary placement with the court within

two court working days after the request for discharge is made. If the petition is not

filed within two court working days, the person must be discharged.

H. Discharge of Persons on Voluntary Status

See § 394.4625(2), Fla. Stat.

A facility must discharge a person on voluntary status under the following

circumstances:

The person has sufficiently improved so that retention in the facility is no

longer clinically appropriate. A person may also be discharged to the care of

a community facility.

The person requests discharge. A person on voluntary status, or a relative,

friend, or attorney of the person, may request discharge either orally or in

writing at any time following admission to the facility. The person must be

discharged within 24 hours of the request, unless the request is rescinded or

the person is transferred to involuntary status. The 24-hour time period may

be extended by a treatment facility (which generally is a state hospital) when

Chapter One History and Overview of Baker Act

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

10

necessary for adequate discharge planning, but must not exceed three days,

exclusive of weekends and holidays.

A person on voluntary status who has been admitted to a facility refuses to

consent to or revokes consent to treatment. Such person must be discharged

within 24 hours after the refusal or revocation unless transferred to

involuntary status or unless the refusal or revocation is freely and voluntarily

rescinded by the person.

IV. Involuntary Examinations – § 394.463, Fla. Stat.; Fla. Admin. Code R.

65E-5.280

A. Criteria

A person may be taken to a receiving facility for involuntary examination if there

is reason to believe that he or she has a mental illness (as defined in the Baker Act)

and because of the mental illness

the person either

o has refused voluntary examination after conscientious explanation and

disclosure of the purpose of the examination, OR

o is unable to determine whether examination is necessary, AND

without care or treatment, the person is likely to either

o suffer from neglect or refuse to care for himself or herself, which “poses

a real and present threat of substantial harm to his or her well-being; and

it is not apparent that such harm may be avoided through the help of

willing family members or friends or the provision of other services,” OR

o cause serious bodily harm to himself or herself or others in the near

future, as evidenced by recent behavior.

§ 394.463(1), Fla. Stat.

B. Initiation of Involuntary Examination

See § 394.463(2), Fla. Stat.

An involuntary examination may be initiated by any one of the three following

means:

Chapter One History and Overview of Baker Act

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

11

A circuit or county court may enter an ex parte order stating that a person

appears to meet the criteria for involuntary examination, specifying the

findings on which that conclusion is based. The ex parte order for

involuntary examination must be based on sworn testimony, written or

oral. No fee can be charged for the filing of a petition for an order for

involuntary examination.

A law enforcement officer, or other designated agent of the court, must take

the person into custody and deliver him or her to an appropriate, or the

nearest, facility within the designating receiving system under section

394.462, Florida Statutes, for involuntary examination. A law enforcement

officer acting in accordance with an ex parte order may serve and execute

such order on any day of the week, at any time of the day or night. A law

enforcement officer acting in accordance with an ex parte order may use

such reasonable physical force as is necessary to gain entry to the premises

and any dwellings, buildings, or other structures located on the premises,

and to take custody of the person who is the subject of the ex parte order.

The officer must execute a written report entitled “Transportation to

Receiving Facility,” detailing the circumstances under which the person was

taken into custody, and the report must be made a part of the person’s

clinical record. Fla. Admin. Code R. 65E-5.260(2).

The ex parte order is valid only until executed or, if not executed, for the

period specified in the order itself. If no time limit is specified in the order,

the order is valid for seven days after the date that the order was signed.

Once a person is picked up on the order and taken to a receiving facility for

involuntary examination and released, the same order cannot be used again

during the time period. The order of the court must be made a part of the

person’s clinical record.

A law enforcement officer must take a person who appears to meet the

criteria for involuntary examination into custody and deliver the person or

have him or her delivered to an appropriate, or the nearest, facility within the

designating receiving system under section 394.462 for examination. The

officer must execute a written report (form CF-MH 3052a) detailing the

circumstances (doesn’t require observations) under which the person was

taken into custody, and the report must be made a part of the person’s

clinical record.

A physician, clinical psychologist, clinical social worker, mental health

Chapter One History and Overview of Baker Act

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

12

counselor, marriage and family therapist, or psychiatric nurse (each as

defined in the Baker Act) may execute a certificate (form CF-MH 3052b)

stating that he or she has examined the person within the preceding 48 hours

and finds that the person appears to meet the criteria for involuntary

examination and stating the observations of the authorized professional

upon which that conclusion is based. A law enforcement officer must take

the person named in the certificate into custody and deliver him or her to an

appropriate, or the nearest, facility within the designating receiving system

under section 394.462 for involuntary examination. The law enforcement

officer must execute a written report detailing the circumstances under

which the person was taken into custody. The report and certificate must be

made a part of the person’s clinical record. (While not authorized by statute,

Florida’s Attorney General wrote on May 28, 2008, that physician assistants

could under specific circumstances initiate Baker Act involuntary

examinations. Op. Att’y Gen. Fla. 08-31 (2008).)

C. Definitions of Professionals

See § 394.455, Fla. Stat.

“‘Physician’ means a medical practitioner licensed under chapter 458 or

chapter 459 who has experience in the diagnosis and treatment of mental

illness or a physician employed by a facility operated by the United States

Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States Department of

Defense.” § 394.455(32), Fla. Stat.

“Physician assistant” means a person licensed under chapter 458 or chapter

459 who has experience in the diagnosis and treatment of metal disorders.”

§ 394.455(33), Fla. Stat.

“‘Psychiatrist’ means a medical practitioner licensed under chapter 458 or

chapter 459 for at least 3 years, inclusive of psychiatric residency.” §

394.455(36), Fla. Stat.

“‘Clinical psychologist’ means a psychologist as defined in s. 490.003(7),

with 3 years of postdoctoral experience in the practice of clinical

psychology, inclusive of the experience required for licensure, or a

psychologist employed by a facility operated by the United States

Department of Veterans Affairs that qualifies as a receiving or treatment

facility under this part.” § 394.455(5), Fla. Stat.

Chapter One History and Overview of Baker Act

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

13

“‘Clinical social worker’ means a person licensed as a clinical social worker

under s. 491.005 or s.491.006.” § 394.455(7), Fla. Stat.

“‘Mental health counselor’ means a person licensed as a mental health

counselor under s. 491.005 or s.491.006.” § 394.455(26), Fla. Stat.

“‘Marriage and family therapist’ means a person licensed as a marriage and

family therapist under s. 491.005 or s.491.006.” § 394.455(25), Fla. Stat.

“‘Psychiatric nurse’ means an advanced registered nurse certified under s.

464.012 who has a master’s or doctoral degree in psychiatric nursing, holds

a national advanced practice certification as a psychiatric mental health

advanced practice nurse, and has 2 years of post-master’s clinical experience

under the supervision of a physician.” § 394.455(35), Fla. Stat.

“’Qualified professional’ means a physician or a physician assistant licensed

under chapter 458 or chapter 459; a psychiatrist licensed under chapter 458

or chapter 459; a psychologist as defined in s. 490.003(7); or a psychiatric

nurse as defined in s. 394.455. § 394.455(38), Fla. Stat.

D. Selected Procedures for Involuntary Examinations

See § 394.463(2), Fla. Stat.

Any receiving facility accepting a person based on a court’s ex parte order, a law

enforcement officer’s report, or a mental health professional’s certificate must send

a copy of the document with the required cover sheet to the Florida Department of

Children and Families (DCF) (via the Baker Act Reporting Center) on the next

working day.

A person can’t be removed from any long-term care program or residential

placement licensed under chapter 400 (nursing homes) or chapter 429, Florida

Statutes (assisted living facilities), and transported to a receiving facility for

involuntary examination unless an ex parte order, a law enforcement officer’s

report, or a mental health professional’s certificate is first prepared. If the condition

of the person is such that preparation of a law enforcement officer’s report is not

practicable before removal, the report must be completed as soon as possible after

removal, but in any case before the person is transported to a receiving facility. A

receiving facility admitting a person for involuntary examination who is not

accompanied by the required ex parte order, mental health professional certificate,

or law enforcement officer’s report must notify DCF of the admission by certified

Chapter One History and Overview of Baker Act

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

14

mail or by email, if available, by the next working day. § 394.463(2)(b), Fla. Stat.

E. Initial Mandatory Examination

See § 394.463(2)(f), Fla. Stat.; Fla. Admin. Code R. 65E-5.2801.

A person must receive an initial mandatory examination by a physician or clinical

psychologist at a facility without unnecessary delay to determine whether the

criteria for involuntary services are met. Emergency treatment may be provided.

This initial mandatory involuntary examination must include:

a thorough review of any observations of the person’s recent behavior;

a review of the document initiating the involuntary examination and the

transportation form;

a brief psychiatric history; and

a timely face-to-face examination of the person to determine if he or she

meets the criteria for release.

The person can’t be released by a receiving facility “without the documented

approval of a psychiatrist or a clinical psychologist or, if the receiving facility is

owned or operated by a hospital or health system, the release may also be approved

by a psychiatric nurse performing within the framework of an established protocol

with a psychiatrist or an attending emergency department physician with

experience in the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness and after completion of

an involuntary examination pursuant to this subsection. A psychiatric nurse may

not approve the release of a patient if the involuntary examination was initiated by

a psychiatrist unless the release is approved by the initiating psychiatrist.”

§ 394.463(2)(f), Fla. Stat. The person must be given prompt opportunity to notify

others of his or her whereabouts.

F. Release from Involuntary Examination

See § 394.463(2)(g), Fla. Stat.

Within the 72-hour examination period, one of the following three actions must be

taken based on the individual needs of the person:

The person must be released unless he or she is charged with a crime, in

which case the person must be returned to the custody of a law enforcement

officer.

The person, unless charged with a crime, must be asked to give express and

Chapter One History and Overview of Baker Act

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

15

informed consent to placement on voluntary status, and, if such consent is

given, the person must be voluntarily admitted. Such transfer from

involuntary to voluntary status must be conditioned on the certification by a

physician that the person has the capacity to make well-reasoned, willful,

and knowing decisions about medical, mental health, or substance abuse

treatment.

A petition for involuntary placement must be completed within 72 hours

and filed with the circuit court for involuntary inpatient placement, or with

the circuit or criminal county court for involuntary outpatient services,

within the 72 hours. If the 72 hours ends on a weekend or holiday, the filing

must be no later than the next working day thereafter.

G. Notice of Discharge or Release

See §§ 394.463(3), 394.469(2), Fla. Stat.

Notice of discharge or transfer of a person must be given as provided in section

394.4599, Florida Statutes. Notice of the release must be given to the individual

and his or her guardian, guardian advocate, health care surrogate or proxy,

attorney, and representative, to any person who executed a certificate admitting the

individual to the receiving facility, and to any court that ordered the individual’s

evaluation.

H. Reporting to DCF

See section 394.463(2)(a), Fla. Stat.

Any receiving facility accepting a person for involuntary examination must send

to DCF via the BA Reporting Center a cover sheet (form CF-MH 3118) and a copy

of the completed initiating form:

ex parte petition/order;

report of law enforcement officer; or

certificate of a professional.

All court orders for involuntary placement must also be sent to the BA Reporting

Center within one day, including:

involuntary inpatient placement order;

involuntary outpatient servicesorder; and

continued involuntary outpatient services order

Chapter One History and Overview of Baker Act

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

16

Receiving facilities must report directly to DCF by certified mail or email, within

one working day, any long-term care facility licensed under chapter 400 or chapter

429, Florida Statutes, that does not fully comply with Baker Act provisions

governing voluntary admissions, involuntary examinations, or transportation.

I. Transportation of Persons for Involuntary Examination

See § 394.462, Fla. Stat.; Fla. Admin. Code R. 65E-5.260.

Law enforcement has no responsibility to transport persons for voluntary

admission. Nor is law enforcement responsible for transferring persons from a

hospital ER where they may have been medically examined or treated to a Baker

Act receiving facility. In the latter case, the person’s transfer is the responsibility of

the sending hospital, pursuant to the federal EMTALA law, 42 U.S.C. § 1395dd.

Regardless of whether the involuntary examination is initiated by the courts, law

enforcement, or an authorized mental health professional, law enforcement is

responsible for transporting the person to the nearest receiving facility, or the

appropriate facility within the designated receiving system, for the

examination.

A law enforcement agency may decline to transport a person to a receiving facility

only when any of the following have occurred:

The county has contracted for transportation at the sole cost to the county,

and the law enforcement officer and medical transport service agree that the

continued presence of law enforcement personnel is not expected to be

necessary for the safety of the person to be transported or others. This statute

requires the law enforcement officer to report to the scene, assess the risk

circumstances, and, if appropriate, “consign” the person to the care of the

transport company.

When a jurisdiction has entered into a county-funded contract with a

transport service for transportation of persons to receiving facilities, such

service must be given preference for transportation of persons from nursing

homes, assisted living facilities, adult day care centers, or adult family care

homes, unless the behavior of the person being transported is such that

transportation by a law enforcement officer is necessary.

A law enforcement officer takes custody of a person under the Baker Act

and assistance is needed for the safety of the officer or the person in custody,

in which case the officer may request assistance from emergency medical

Chapter One History and Overview of Baker Act

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Baker Act Benchguide November 2016

17

personnel.

If the law enforcement officer believes that a person has an emergency

medical condition, the person may be first transported to a hospital for

emergency medical treatment, regardless of whether the hospital is a

designated receiving facility. An emergency medical condition is defined in

chapter 395, Florida Statutes, as a “medical condition manifesting itself by

acute symptoms of sufficient severity, which may include severe pain, such

that absence of immediate medical attention could reasonably be expected to

result in” serious jeopardy to patient health (including pregnant women and

their fetus), serious impairment to bodily functions, or serious dysfunction of

any bodily organ or part. § 395.002(8), Fla. Stat.

Once the person is delivered by law enforcement to a hospital for emergency

medical examination or treatment and the person is placed in the hospital’s

care, the officer’s responsibility for the person is over, assuming no criminal