1

Peter S. Menell

Koret Professor of Law

Director, Berkeley Center for Law and Technology

University of California, Berkeley School of Law

686 Simon Hall, MC 7200

Berkeley, CA 94720

(510) 642-5489

23 May 2014

U.S. Copyright Office

Library of Congress

Re: Comments of Professor Peter S. Menell – Music Licensing Study

Docket No. 2014–03

In response to the March 17, 2014 Federal Register Notice (78 Fed. Reg. 14739) soliciting

comments on the Copyright Office’s “Music Licensing Study,” I submit these comments solely

on my own behalf as an intellectual property law scholar.

Prefatory Remarks

Before turning to the specific enumerated questions posed in the Federal Register Notice,

it will be useful to put the music licensing study in a broader perspective. As I explored in the

42

nd

Annual Brace Lecture – “This American Copyright Life: Reflections on Re-equilibrating

Copyright Law for the Internet Age” Journal of the Copyright Society of the U.S.A. (forthcoming

2014) (hereinafter cited as “This American Copyright Life”) (page proofs attached) – the Internet

has profoundly altered the functioning of the copyright system over the past 15 years. Many of

the substantial changes have occurred since the enactment of the Digital Millennium Copyright

Act of 1998. While the Internet’s capacity has substantially reduced the age-old costs of

distributing works of authorship, the promiscuity of Internet distribution has produced

unprecedented enforcement challenges.

These changes have had particularly significant impacts on the music marketplace. While

Internet functionality opened up new distribution modes (such as iTunes, Pandora, and Spotify), it

also fueled rampant unauthorized distribution of copyrighted musical works and sound

recordings.

As “This American Copyright Life” explains (pages 237-48), copyright law is but one

component of society’s larger content governance ecosystem. Technology, markets, and social

norms also play important roles. Whereas technological and legal protections effectively

channeled consumers into markets for copyrighted works throughout much of copyright law’s

history, file-sharing technologies have afforded Internet users easy access to all manner of

copyrighted works without the need to go through market institutions. Technology companies

and copyright industries have sought to “compete” with such unauthorized access through new

online services – such as iTunes, Vevo, Pandora, and Spotify – but with only limited success. The

level of unauthorized distribution of copyrighted works remains high.

Improving the functioning of music licensing markets is critical to the efficacy of the

copyright system. While digital rights management technologies have achieved some success in

2

particular content marketplaces – such as Massively Multiplayer Online Role-Playing Game

(MMORPG) platforms – the music marketplace has proven far more resistant to technological

solutions. See Peter S. Menell, Envisioning Copyright Law’s Digital Future, 46 N.Y.L. School L.

Rev. 63, 121 n.168,165, 178-79 (2002-2003) (discussing the failure of the Secure Digital Music

Initiative (SDMI)). The carrot of robust, fairly priced music services will prove far more effective

than the stick of costly, aggressive civil enforcement campaigns against end users in bringing

many music fans back into authorized online music services. See “This American Copyright

Life” (pages 218-35, 325-37).

These considerations lead me to call attention to three areas of inquiry: (I) establishing

robust registries for licensing music; (II) promoting fair and balanced music streaming services;

and (III) channeling mash-up creativity into authorized markets.

I. Copyright Notice as the Foundation for Music Licensing (Topic 24)

The availability of transparent, accessible, and easily searchable registries of copyrightable

works would provide a foundation for robust music licensing. See generally Peter S. Menell &

Michael J. Meurer, Notice Failure and Notice Externalities, 5 J. Legal Analysis 1 (2013). Due to

the lack of registration requirements and reliable databases for tracking music ownership, music

services incur duplicative and high costs in efforts to build digital music markets. They also face

unnecessary liability for inadvertently distributing works without requisite authorization.

Copyright law and the Copyright Office can and should play a central role in supporting robust

copyright licensing through registration and related services. See “This American Copyright

Life” at 310-12. Databases should be standardized and easily accessible to the public.

II. A Fair and Balanced Licensing Platform for Music Streaming Services (Topics 18-21)

Digital and Internet technology have brought about the capacity to afford widespread

access to the proverbial “celestial jukebox” – universal access to all sound recordings through

convenient technologies. Consumers are increasingly migrating from downloading music toward

streaming services, such as Spotify, Pandora, and Beats. It seems likely that this transition will

continue. Once consumers become accustomed to these services, their music listening habits

adapt as they develop playlists and integrate music listening with social networking. These

services achieve many of the aspirations of music fans.

Yet the adoption of these services and their ability to promote musical creativity are

hampered by distortions in the music marketplace. Most music fans will not join a streaming

service unless it offers a relatively broad catalog, including sound recordings controlled by the

major record labels. As I explain in “This American Copyright Life” (pages 258-63, 327-32), the

major record labels have leveraged their control of the “legacy” catalog to disadvantage not only

their own artists but also independent artists. This equilibrium undermines artist and consumer

support for an authorized celestial jukebox, the best antidote to music piracy. More generally, it

deprives future creators of the promise of earning an appropriate return on their creative efforts.

Addressing this fundamental distortion is critical to building a fair and balanced marketplace for

creative musical artists in the Internet Age.

3

III. Promoting Mash-Ups (Topic 17)

Like rhythm and blues, rock ‘n roll, rap, and hip hop, mash-ups of previously recorded

music have emerged as the latest musical genre. Yet this genre operates largely beyond any

authorized marketplace. The costs of negotiating the many licenses that would be needed to clear

such works is prohibitive for many mash-ups. See generally Kembrew McLeod & Peter DiCola,

Creative License: The Law and Culture of Digital Sampling (2011). Furthermore, just as

consumers have the option of obtaining copyrighted works outside of legitimate channels in the

Internet Age, they also have the ability to produce and distribute mash-ups. Consequently, much

of the mash-up culture flourishes through unauthorized channels.

While some have suggested that mash-ups do not require permission because they qualify

for fair use treatment, such a legal interpretation would deprive the creators of the works being

sampled any share of the social value that they create beyond possible modest promotional value.

I suggest in “This American Copyright Life” (pages 318-24) that there could be substantial value

in developing a compulsory license for mash-ups. By so doing, Congress would encourage

younger generations to participate in authorized marketplaces for musical works. The creators of

such mash-ups could more easily derive income from their creative efforts while providing added

value to creators of works that are sampled. While such a regime would be more complicated

than the present cover license and would authorize greater adaptation, failure to open up such a

channel for this new and increasingly popular genre means that creators of the sampled works will

see little if any income for such uses. Developing a robust and flexible regime for mash-ups

would, like the cover license, promote new forms of cumulative creativity while providing more

appropriate encouragement and compensation to those whose works are sampled.

Respectfully submitted,

Peter S. Menell

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 1 1-MAY-14 10:19

This American Copyright Life 201

THIS AMERICAN COPYRIGHT LIFE:

REFLECTIONS ON RE-EQUILIBRATING COPYRIGHT

FOR THE INTERNET AGE

by P

ETER

S. M

ENELL

*

ABSTRACT

This article calls attention to the dismal state of copyright’s public

approval rating. Drawing on the format and style of Ira Glass’s “This

American Life” radio broadcast, the presentation unfolds in three parts:

Act I – How did we get here?; Act II – Why should society care about

copyright’s public approval rating?; and Act III – How do we improve

copyright’s public approval rating (and efficacy)?

*Koret Professor of Law, University of California at Berkeley School of Law and

co-founder and Director, Berkeley Center for Law & Technology. I owe special

thanks to David Anderman, Mark Avsec, Robby Beyers, Jamie Boyle, Hon. Ste-

phen G. Breyer, Andrew Bridges, Elliot Cahn, David Carson, Jay Cooper, Jeff

Cunard, Victoria Espinel, David Given, Jane Ginsburg, Paul Goldstein, Jim Grif-

fin, Dylan Hadfield-Menell, Noah Hadfield-Menell, Scotty Iseri, Dennis Karjala,

Rob Kasunic, Chris Kendrick, Mark Lemley, Larry Lessig, Jessica Litman, Rob

Merges, Eli Miller, Neal Netanel, Hon. Jon O. Newman, Wood Newton, David

Nimmer, Maria Pallante, Shira Perlmutter, Marybeth Peters, Gene Roddenberry,

Pam Samuelson, Ellen Seidler, Lon Sobel, Chris Sprigman, Madhavi Sunder, Gary

Stiffelman, Pete Townshend, Molly Van Houweling, Fred von Lohmann, Joel

Waldfogel, Jeremy Williams, Jonathan Zittrain, and the participants on the Cyber-

prof and Pho listserves for inspiration, perspective, provocation, and insight; and

Claire Sylvia for her steadfast love, encouragement, and support. None of these

people bear responsibility for what follows — and I suspect many will disagree

with some or all of what I have to say. My hope is that the dot product of the

reactions achieves the golden mean.

Following my presentation of the Brace Lecture, I had the opportunity to re-

prise the lecture at Cardozo Law School, George Washington Law School (and the

D.C. Chapter of the Copyright Society), Hebrew University, Indiana University,

the Northern California Chapter of the Copyright Society, Sony Pictures, Tel Aviv

University, U.S. Copyright Office, University of California at Berkeley, University

of California at Davis, University of California (Hastings), University of Penn-

sylvania, and the USC Intellectual Property Conference Speakers’ Dinner. I thank

Shyam Balganesh, Stefan Bechtold, Bob Brauneis, Ben Depoorter, Kristelia Gar-

cia, Naomi Jane Gray, Justin Hughes, Linda Joy Kattwinkel, Joesph Liu, Mike

Mattioli, David Morrison, Maria Pallante, Madhavi Sunder, Aimee Wolfson, Felix

Wu, Christopher Yoo, and the numerous law students and copyright professionals

who shared their reactions.

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 2 1-MAY-14 10:19

202 Journal, Copyright Society of the U.S.A.

CONTENTS

ACT I: HOW DID WE GET HERE? ........................... 207

R

A. Copyright Enforcement in the Analog Age............ 210

R

B. The Gathering Digital Copyright Storm ............... 214

R

C. The Perfect Copyright Storm ......................... 216

R

D. The Digital Copyright Enforcement Saga.............. 218

R

ACT II: WHY SHOULD SOCIETY CARE ABOUT

COPYRIGHT’S PUBLIC APPROVAL RATING? ....... 236

R

A. Content Governance: From the Analog Age to the

Internet Age ......................................... 237

R

B. Reflections on Popular Music and Independent Film in

the Internet Age ..................................... 239

R

1. Popular Music: Creators Caught in a Dual Vise . . . 239

R

2. Popular Films: Anytime, Anywhere, and Free ..... 254

R

C. The Copyright/Internet Paradox ...................... 257

R

1. Digital Music Platform Pathology ................. 258

R

2. Digital Film Platform Pathology................... 263

R

ACT III: HOW DO WE IMPROVE COPYRIGHT’S PUBLIC

APPROVAL RATING (AND EFFICACY)? ............. 264

R

A. Legislative Agenda ................................... 268

R

1. Dual Enforcement Regime........................ 268

R

a) Non-Commercial/Small-Scale Infringers ....... 269

R

(1) Re-calibrating Statutory Damages ......... 272

R

(2) Expanded Subpoena Power for Detecting

File-Sharers ............................... 273

R

(3) Confirming the Making Available Right . . . 274

R

(4) Encouraging Responsibility for Web Access

Points .................................... 277

R

(5) A Small Claims Processing Institution for

File-Sharing Infringements ................ 277

R

b) Commercial/Large Scale Infringers ............ 278

R

(1) Re-calibrating Statutory Damages ......... 279

R

(2) Instituting Balanced Public Enforcement . . 283

R

(a) A Balanced Public Enforcement

Process ................................. 295

R

(b) Working Collaboratively Across the

Content and Technology Sectors ........ 297

R

(c) Balanced International Efforts to

Promote Copyright Protection .......... 301

R

c) Whistleblower Bounties ....................... 303

R

2. Promoting Cumulative Creativity.................. 305

R

a) Academic Research ........................... 306

R

b) Digital Archiving and Search.................. 308

R

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 3 1-MAY-14 10:19

This American Copyright Life 203

c) Orphan Works ................................ 310

R

d) Operationalizing Fair Use ..................... 312

R

e) Experimental and Self-Expressive Use ........ 314

R

f) Photography of Public Art .................... 316

R

g) Remix Compulsory License ................... 318

R

h) Enhanced Penalties for Abuse of the Notice

and Takedown System ........................ 324

R

B. Market-Based Solutions .............................. 325

R

1. The Grand Kumbaya Experiment ................. 327

R

2. Graduated Embrace .............................. 332

R

CONCLUSIONS ................................................ 337

R

I am deeply honored to deliver the Brace Lecture, which has long

served as a platform for celebrating, understanding, and addressing the

challenges of the copyright system.

1

I dare say that at no time in the Brace

Lecture’s forty-two year history, or for that matter, copyright law’s 300

year history, has the copyright system been more severely criticized as

being out of touch and out of date.

We are now thirteen years since Napster’s revolutionary appearance

— what seems like an eternity in the rapidly evolving Internet Age. My

law students have come of age in the post-Napster era. Netizens who were

in high school when peer-to-peer functionality went viral are now beyond

the age at which no one should be trusted.

2

We have since seen the rise of

innumerable file-sharing and cyberlocker services. The emergence of the

Internet as a principal platform for distributing works of authorship has

1

Prior Brace lecturers include many of the most influential copyright jurists,

practitioners, and academics. I have had the honor to learn from and, in

two cases, collaborate with prior Brace lecturers — David Nimmer, Paul

Goldstein, Mark Lemley, and Jane Ginsburg. I also want to recognize

special debts to the Honorable Stephen G. Breyer and the Honorable Jon

O. Newman. I had the opportunity to write my first article on copyright law

— Tailoring Legal Protection for Computer Software, 39

S

TAN

. L. R

EV

.

1329 (1987) — in a seminar led by then-Judge, now Justice, Breyer. His

economic and policy orientation resonated with my graduate studies in law

and economics and has provided a valuable foundation throughout my

career. Following law school, I had the privilege to clerk for Judge Newman

on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. His deep interest in

copyright jurisprudence and legislative history very much influenced my

own understanding, appreciation, and interest in this extraordinary and

dynamic field.

2

The 1960s phrase “Don’t Trust Anyone Over 30” was first uttered by Jack

Weinberg, a UC Berkeley student involved with the Free Speech

Movement, in an interview with the San Francisco Chronicle in 1964. See

Don’t Trust Anyone Over 30, Unless It’s Jack Weinberg,

B

ERKELEY

D

AILY

P

LANET

(Apr. 6, 2000), http://www.berkeleydailyplanet.com/issue/2000-04-

06/article/759.

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 4 1-MAY-14 10:19

204 Journal, Copyright Society of the U.S.A.

focused public opinion on copyright law like at no other time in

copyright’s long history. As last year’s cataclysmic battle over the Stop

Online Piracy Act (SOPA) revealed, the glare of public opinion can be

harsh.

3

For those reasons, I would like to begin this year’s Brace Lecture by

calling attention to a topic that has not attracted much attention at such

staid gatherings: copyright’s public approval rating. For reasons that I will

explain, the public’s perception of the copyright system has become

increasingly central to its efficacy and vitality. I believe that copyright’s

role in promoting progress in the creative arts, freedom, and democratic

values depends critically upon restoring public support for its purposes

and rules.

Rather than approach this lecture as merely an opportunity to present

an academic paper, I have chosen a more personal and confessional

approach. I hope that this will be more entertaining than a traditional

lecture. But more importantly, I hope that my journey will better

communicate the difficult challenges confronting the copyright system and

reveal key insights for sustaining and improving it.

The confessional aspect of my story revolves around my struggle with

what I will call technology-content schizophrenia

4

— a disorder that has

not yet been recognized by the American Psychiatric Association.

5

From

my earliest memories, I was drawn to both technological innovation and

artistic creativity. As an adolescent, rock ‘n roll music inspired “My

Generation,”

6

providing an outlet and voice for our frustrations and desire

to rebel against the injustice that surrounded us. Bob Dylan’s anthems

brought the values of the civil rights and anti-war movements into popular

3

See

A

RAM

S

INNREICH

, T

HE

P

IRACY

C

RUSADE

: H

OW THE

M

USIC

I

NDUSTRY

’

S

W

AR ON

S

HARING

D

ESTROYS

M

ARKETS AND

E

RODES

C

IVIL

L

IBERTIES

(2013).

4

The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language defines

“schizophrenia” as “[a] situation or condition that results from the

coexistence of disparate or antagonistic qualities, identities, or activities.”

Definition of Schizophrenia,

A

MERICAN

H

ERITAGE

D

ICTIONARY

, http://

education.yahoo.com/reference/dictionary/entry/schizophrenia (last visited

Nov. 4, 2013).

5

See

A

M

. P

SYCHIATRIC

A

SS

’

N

, D

IAGNOSTIC AND

S

TATISTICAL

M

ANUAL OF

M

ENTAL

D

ISORDERS

(5th ed. 2013).

6

See My Generation,

W

IKIPEDIA

, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/My_Generation

(last visited Nov. 4, 2013). Pete Townshend’s anthems would feature

prominently in my formative years. He told Rolling Stone magazine that

“‘My Generation’ was very much about trying to find a place in society.”

See id.

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 5 1-MAY-14 10:19

This American Copyright Life 205

culture. How better to understand the Nixon years than through Pete

Townshend’s “Won’t Get Fooled Again?”

7

At the same time, rock ‘n roll fueled my interest in the technology for

reproducing and performing music. Movies, television shows, and books

transported me from a drab, homogeneous suburban New Jersey

neighborhood to all parts of the globe, historical moments, diverse

cultures, and futuristic and distant planets. Calculators and primitive

computers were the most tantalizing toys. Creative arts and technology

coexisted without conflict during my formative years. I enjoyed tinkering

with technology and art, from building stereo amplifiers to making mix

tapes, as much as I loved the music that blasted from my homemade stereo

speakers and customized car stereo. Both music and technology shaped

my values and interests.

As a graduate student, my frustration with the exorbitant cost of

IBM’s Personal Computer led me to the economics of network

technologies and intellectual property and antitrust law. I came to see that

expansive copyright protection for computer software could undermine

both rapid innovation and network externalities.

8

These experiences led

me, more than two decades ago, to lay the groundwork for a research,

teaching, and public policy center focused on law and technology at the

University of California at Berkeley. We envisioned the Berkeley Center

for Law & Technology (BCLT) as a place to support both technological

innovation and expressive creativity.

9

Shortly after BCLT’s formation, students approached me about

expanding the curriculum to include entertainment law. BCLT had

recently hosted one of the first conferences on “Digital Content” and it

was increasingly clear that the future of the Internet would be as much

about the content that flowed through this extraordinary network as the

network itself. Although my intellectual property research up until that

time had focused on software protection, I embraced the students’

7

“Won’t Get Fooled Again” appeared as the final track on The Who’s 1971

album Who’s Next. It captured the frustration, hypocrisy, and cynicism of

the power structures defining our era — “We were liberated from the fall

that’s all, But the world looks just the same”; “meet the new boss, same as

the old boss” — punctuated by the greatest scream in rock ‘n roll history (in

my humble opinion).

8

See Peter S. Menell, Tailoring Legal Protection for Computer Software, 39

S

TAN

. L. R

EV

. 1329 (1987).

9

BCLT’s mission statement has been “to foster the beneficial and ethical

understanding of intellectual property (IP) law and related fields as they

affect public policy, business, science and technology.” About Berkeley

Center for Law & Technology,

B

ERKELEY

C

ENTER FOR

L

AW

&

T

ECHNOLOGY

,

http://www.law.berkeley.edu/5065.htm (last visited Nov. 4,

2013).

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 6 1-MAY-14 10:19

206 Journal, Copyright Society of the U.S.A.

suggestion and began teaching a course exploring the role of intellectual

property in the entertainment industries.

Things were chugging along well. The dot-com explosion enabled

BCLT to build a strong foundation with connections to both Silicon Valley

and Hollywood. Yet growing rancor over the Commerce Department’s

White Paper

10

and the WIPO Copyright Treaties

11

created controversy,

although it was largely confined to industry experts and policy wonks.

Even the passage of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act

12

did not

register significantly in the public consciousness.

This calm would change suddenly mid-1999. The release of Napster’s

file-sharing software would bring the two pillars of my life into conflict.

By the first session of my Introduction to Intellectual Property class in

January 2000, nearly all of my students had been swept up by the Napster

tsunami. When I posed the question of how this technology might affect

the flow of creative works, my students were incapable of seeing past the

euphoria of gaining access to nearly any sound recording at zero cost

through Napster’s charismatic technology.

13

And I would have to admit

that sixteen-year-old me would have found this technology comparably

irresistible.

Digital technology would bring about more than merely easy (and

free) access to popular music, movies, and television shows. Digital

advances enabled the population at large to easily and seamlessly remix or

mash-up copyrighted works, appealing to a universal human desire to

engage, connect to, and personalize creative works. Sixteen-year-old me

would have adored these tools, just as the current version of me has

embraced digital technology for teaching, entertainment, and self-

expression.

This lecture shares my struggle to make sense of these apparently

conflicting ideals — juxtaposing the importance of intellectual property

protection for promoting creative arts with the inherent human desire to

gain access to and engage creative works. It uses remix tools and

10

See

B

RUCE

A. L

EHMAN

, U.S. P

ATENT AND

T

RADEMARK

O

FFICE

,

I

NTELLECTUAL

P

ROPERTY AND THE

N

ATIONAL

I

NFORMATION

I

NFRASTRUCTURE

: T

HE

R

EPORT OF THE

W

ORKING

G

ROUP ON

I

NTELLECTUAL

P

ROPERTY

R

IGHTS

(1995) [hereinafter IPNII White Paper],

available at http:// www.uspto.gov/web/offices/com/doc/ipnii/ipnii.pdf.

11

See WIPO Copyright Treaty, Dec. 20, 1996,

S. T

REATY

D

OC

. N

O

.

105-17, 36

I.L.M. 65 (1997); WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty, Dec. 20,

1996,

S. T

REATY

D

OC

. N

O

. 105-17, 36 I.L.M. 76 (1997).

12

Pub L. No. 105-304, 112 Stat. 2860.

13

See Lior Jacob Strahilevitz, Charismatic Code, Social Norms, and the

Emergence of Cooperation on the File-Swapping Networks, 89

V

A

. L. R

EV

.

505 (2003).

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 7 1-MAY-14 10:19

This American Copyright Life 207

transformative appropriation to illuminate the copyright system’s difficult

adaptation to the Internet Age.

Drawing on the format and the style of Ira Glass’s “funny, dramatic,

surprising, and true” This American Life radio broadcast,

14

I have

fashioned “This American Copyright Life” into a three part story: Act I —

How did we get here?; Act II — Why should society care about

copyright’s public approval rating?; and Act III — How do we improve

copyright’s public approval rating (and efficacy)?

ACT I: HOW DID WE GET HERE?

It is useful to ask why copyright’s public approval rating has not, until

the past decade and a half, attracted much attention. The answer lies

largely in the evolution of technologies for distributing creative works. I

offer a perspective which, judging from the age profile of the audience,

might spark some nostalgia. Many of us first experienced the copyright

system during an era in which the options for accessing copyrighted works

were limited. Films were released to motion picture theaters and eventu-

ally broadcast on television. Television shows were available at designated

times through television broadcasts. Recorded music was available at re-

cord stores or broadcast on radio. Books could be found in bookstores or

libraries.

In that bygone era, consumers had relatively little awareness of, or

interaction with, the copyright system. We did not think much about the

copyright system because we largely lacked the technological capacity to

do much with copyrighted works beyond experience them. We anxiously

awaited new films, albums, novels, magazines, comic books, and television

shows. To the extent that we considered the “copyright system” as such,

our views largely paralleled our enjoyment of the works that content in-

dustries produced. If we liked the content, the system was working.

In my own case, the products of the content industries were deeply

engaging and inspiring. I still vividly remember seeing my first episode of

the original Star Trek series while at a sleepover with my much older (a

few years) cousins. Gene Roddenberry’s extraordinary voyages of the

Starship Enterprise — “to boldly go where no man has gone before” —

had a profound influence on my social values and interest in technology.

Rebellious rock ’n roll music spoke to “My Generation”

15

— fueling our

innate adolescent desire to question authority and think independently. I

14

See

T

HIS

A

MERICAN

L

IFE

,

http://www.thisamericanlife.org (last visited Nov. 4,

2013).

15

“My Generation” is the title of The Who’s classic 1965 anthem. See My Gener-

ation,

W

IKIPEDIA

, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/My_Generation (last visited

Nov. 4, 2013). It was named the eleventh greatest song by Rolling Stone

magazine. Although I was too young to have been in the original audience

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 8 1-MAY-14 10:19

208 Journal, Copyright Society of the U.S.A.

don’t know how I would have survived the anxieties, indulgences, and con-

tradictions of “teenage wasteland” without Pete Townshend’s rock bal-

lads

16

or Bob Dylan’s forthright poetry. If the copyright system promoted

this art, then I was a fan. But frankly, I had little reason to think much

about the connection between copyright and the inspiring music, film,

literature, and art that captivated and shaped me.

This is not to say that I did not seek to use technology as a means to

gain greater access to and enjoyment of copyrighted works. Popular music

and Hollywood’s visions of a just technological/digital future fueled my

precocious techie tendencies. I sought out the latest in recording technol-

ogy, experimented with primitive computers, and repaired and recon-

structed bicycles (and later a very used, abused, and largely rusted out

Fiat). Along with a friend, I built stereo amplifiers and high fidelity speak-

ers and designed and installed home and car stereo systems. I subscribed

to Stereo Review and many a record club (only to quit as soon as I sur-

passed the minimum requirements needed to secure the heavily dis-

counted albums). I spent a lot of time in record, stereo, hardware, and

electronics shops with my close friend and partner in mischief Chris Ken-

drick. We experimented with the primitive recording technologies of the

time, producing quite a few mix tapes.

It was not entirely surprising, therefore, when Robby Beyers, a high

school classmate who was an avid photographer, approached me about

“mixing” the soundtrack for a multi-screen slide show that he was plan-

ning for our high school graduation. Copyright infringement never

crossed my mind as Chris and I spliced together popular, copyright-pro-

tected musical compositions and sound recordings. We recorded this early

“mash-up” — featuring a clip from the soundtrack of the then-popular

television series Mash — on one track. Robby used a primitive computer

to place dissolve commands for the six carousel projectors on the other

track. The resulting show was a great success, bringing tears to the eyes of

parents, graduating seniors, and teachers alike. I don’t recall anyone sug-

gesting that we had violated copyright law — and in any case, the statute

for this song, it became a favorite as my appreciation for The Who’s music

grew.

16

“Teenage wasteland” is the most resonant refrain from The Who’s classic

“Baba O’Riley.” See Baba O’Riley,

W

IKIPEDIA

, http://en.wikipedia.org/

wiki/Baba_O%27Riley (last visited Nov. 5, 2013). It was released on The

Who’s Who’s Next, one of the two most memorable albums of my youth.

The Who’s rock opera Quadrophenia, released in 1973, offered a deeper,

more personal, sociological, and psychological perspective for my genera-

tion. The use of the “quadrophonic” metaphor and story-telling device

(four distinct and contradictory voices) resonated with confused teens strug-

gling to find their identity in a world defined by conventional molds.

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 9 1-MAY-14 10:19

This American Copyright Life 209

of limitations has long since passed.

17

The overwhelming sentiments were

admiration for youthful ingenuity and the wonders of “modern” technol-

ogy — a “computerized” slide show. And perhaps that extraordinary

show — owing principally to Robby’s vision and talent — helped some of

our classmates better appreciate those of us who avoided the high school

spotlight.

18

Thus, if one were to have gauged my opinion as well as public opinion

of “My Generation” regarding the copyright system at that time, it would

no doubt have been neutral to overwhelmingly positive, as depicted in Fig-

ure 1. “My Generation” did not see copyright as an oppressive regime.

We thrived in ignorant bliss well below copyright’s enforcement radar and

were inspired by content industry products.

The situation could not be more different for adolescents, teenagers,

college students, and netizens today. Many perceive copyright to be an

overbearing constraint on creativity, freedom, and access to creative

works.

19

Although they might recognize copyright’s role in producing

works that they enjoy, they consider copyright laws to be punitive, chilling,

backward, and poorly attuned to the needs of their generation. I don’t, at

this juncture of the lecture, want to evaluate their perceptions and emo-

tions but rather to examine the reasons for this shift in perceptions. As

the foregoing personal history suggests, I relate to my students and my

teenage/twenty something sons in their passion for copyrighted works and

their desire to use technology to enhance their enjoyment of creativity and

to express themselves. I am moved by some of Hollywood’s releases, anx-

17

See 17 U.S.C. § 507 (2012).

18

Robby would go on to earn his B.S. in Chemical Engineering and M.S. and

Ph.D. in Materials Science at Stanford, where he became the photographer

for Stanford’s irreverent marching band. We would reconnect for two years

while I pursued a Ph.D. in economics at Stanford. Robby subsequently au-

thored more than forty technical papers, including invited review articles

for Solid State Physics and the Annual Review of Materials Science and led a

group at IBM’s Almaden Research Center, becoming a co-inventor on sev-

eral patents, including the basic patent on single-wall carbon nanotubes.

Although I had him pegged for a Nobel Prize, his career took a surprising

turn in the mid-1990s when he enrolled at Santa Clara University’s night

law school. Robby completed his J.D. in 2000 and M.B.A. in 2001. He is

now a partner in a leading Silicon Valley IP law practice, where he develops

patent portfolios for a number of computing and Internet-related

companies.

19

See

J

AMES

B

OYLE

, T

HE

P

UBLIC

D

OMAIN

: E

NCLOSING THE

C

OMMONS OF THE

M

IND

(2008);

L

AWRENCE

L

ESSIG

, F

REE

C

ULTURE

: H

OW

B

IG

M

EDIA

U

SES

T

ECHNOLOGY AND THE

L

AW T O

L

OCK

D

OWN

C

ULTURE AND

C

ONTROL

C

REATIVITY

(2004);

S

IVA

V

AIDHYANATHAN

, C

OPYRIGHTS AND

C

OPYWRONGS

, T

HE

R

ISE OF

I

NTELLECTUAL

P

ROPERTY AND

H

OW IT

T

HREATENS

C

REATIVITY

(2001);

L

AWRENCE

L

ESSIG

, C

ODE AND

O

THER

L

AW S O F

C

YBERSPACE

(2000).

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 10 1-MAY-14 10:19

210 Journal, Copyright Society of the U.S.A.

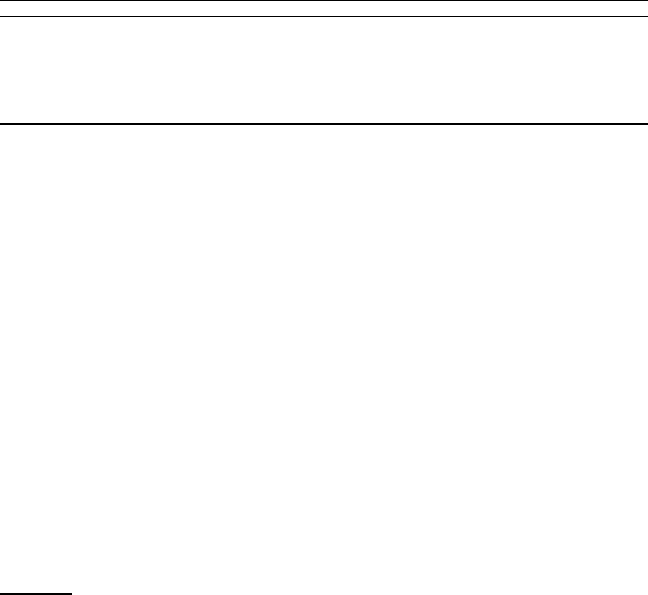

Figure 1

Copyright Public Approval Rating

100

80

60

40

20

1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010

Source: completely made up; but possibly accurate

iously await broadcasts of The Big Bang Theory and Modern Family, cher-

ish great novels, and hope for new Foo Fighters releases.

This Act sets the stage for understanding why the post-Napster gener-

ation’s perceptions of the copyright system are far more important to the

functioning of the copyright system than were the perceptions of “My

Generation.” The story begins with the development of the copyright en-

forcement regime during the Analog Age — a period in which copyright

enforcement played a relatively modest role in the overall functioning of

the copyright system. We will then trace how the rules and institutions

that developed in the Analog Age backfired in the Internet Age.

A. Copyright Enforcement in the Analog Age

For much of the last century, the technology of reproducing works of

authorship as well as business practices made enforcement manageable. It

was costly to reproduce books and relatively easy to detect large-scale

piracy. Booksellers had ongoing relationships with publishers. Hence

they would have a lot of explaining to do if their competitors were selling

large amounts of best sellers and they had no sales. Purchasing supplies

from unauthorized sources exposed the renegade bookseller, thereby

jeopardizing their critical business relationships. Without the ability to hit

substantial volume, book piracy was a marginal business at best in devel-

oped economies with copyright laws.

Motion picture studios had an even tighter grip over their distribution

chain. They did not sell their product. Rather they leased film reels to

theaters and were paid based on box office revenues. The major problem

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 11 1-MAY-14 10:19

This American Copyright Life 211

that the industry experienced was “bicycling”

20

— unscrupulous theater

owners who would “bicycle” films around the corner to another venue and

sneak in some off-the-books shows. The film industry hired investigators

to look for advertisements of such showings. The impact on the industry

was modest.

The music industry faced two substantial enforcement issues — com-

pliance with the public performance right and, much later, record piracy.

Music composers and publishers formed the American Society of Com-

posers, Authors and Publishers (ASCAP) in 1914 to protect public per-

formance rights. Through a series of test cases, ASCAP established broad

protection for musical compositions.

21

It was able to attract many of the

leading composers and music publishers of the day, enabling them to offer

a “blanket” license scaled to the business and institutions publicly per-

forming ASCAP compositions.

22

The idea was to charge a relatively mod-

est percentage fee across a large base of entities performing copyrighted

musical compositions in ASCAP’s growing inventory and use sampling

methods to divvy up the pool. The blanket system greatly economized on

enforcement costs, but entailed a large education and enforcement cam-

paign. The model began to generate substantial net revenue for distribu-

tion as the radio industry took off in the 1930s.

23

20

See

K

ERRY

S

EGRAVE

, P

IRACY IN THE

M

OTION

P

ICTURE

I

NDUSTRY

(2003); see

Bernard R. Sorkin, A Geriatric View of Motion Picture Piracy, 51

J. C

OPY-

RIGHT

S

OC

’

Y

237, 237 (2003).

21

See, e.g., Herbert v. Shanley, 242 U.S. 591 (1917) (holding that hotels and res-

taurants which performed music must compensate composers even if pa-

trons are not charged separately for the musical entertainment); Jerome H.

Remick & Co. v. General Electric Co., 16 F.2d 829 (S.D.N.Y. 1926) (radio

broadcasts); Buck v. Lester, 24 F.2d 877 (E.D.S.C. 1928) (motion picture

theaters); Buck v. Milam, 32 F.2d 622 (D. Idaho 1929) (dance hall); Buck v.

Jewell-La Salle Realty Co., 283 U. S. 191 (1931) (hotels).

22

See Robert P. Merges, Contracting into Liability Rules: Intellectual Property

Rights and Collective Rights Organizations, 84

C

AL

. L. R

EV

.

1293, 1328-40

(1996).

23

After initially offering the nascent industry low rates, ASCAP ramped up its

rates over 400% between 1931 and 1939. See American Society of Compos-

ers, Authors and Publishers,

W

IKIPEDIA

,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ameri

can_Society_of_Composers,_Authors_and_Publishers (last visited Nov. 4,

2013). When ASCAP sought to double its rates again in 1940, radio broad-

casters formed a boycott of ASCAP music and formed the rival perform-

ance rights organization, Broadcast Music Inc. (BMI), to compete with

ASCAP. See

R

USSELL

S

ANJEK

, P

ENNIES

F

ROM

H

EAVEN

: T

HE

A

MERICAN

P

OPULAR

M

USIC

B

USINESS IN THE

T

WENTIETH

C

ENTURY

(1996). By that

year, the broadcasting industry was bringing in over $200 million in gross

revenues, of which $4 million or about 2% was being paid out to ASCAP.

See Marcus Cohn, Music, Radio Broadcasters and the Sherman Act, 29

G

EO

.

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 12 1-MAY-14 10:19

212 Journal, Copyright Society of the U.S.A.

Like bookstores, record stores were disinclined to vend unauthorized

pirated goods. The record labels had long-term relationships with distri-

bution channels and could detect substantial variations in sales.

It was against this backdrop that Congress set out to draft compre-

hensive copyright reform — what would eventually become the Copyright

Act of 1976 — in the mid 1950s. In 1955, Congress authorized appropria-

tions over the next three years for comprehensive research and prepara-

tion of studies by the Copyright Office as the groundwork for general

revision. It was expected that this reform would be completed by the early

to mid-1960s. The bulk of the reform was completed by 1965, but contro-

versy over the treatment of the nascent cable television industry delayed

passage. The end of the story is well known — the long and complex

Copyright Act of 1976.

A significant part of the copyright system’s pathology relates to the

statutory damages regime, so it will be worthwhile tracing the develop-

ment of those provisions. From the nation’s founding, Congress has pro-

vided for the award of statutory damages for copyright infringements.

24

As Congress would explain in the lead-up to the 1976 Copyright Act, the

“need for this special remedy arises from the acknowledged inadequacy of

actual damages and profits in many cases” due to the inherent difficulties

of detecting and proving copyright damages.

25

What Congress had in

mind was the public performance of music. The Register of Copyright’s

1961 Report noted that

[i]n many cases, especially those involving public performances, the only

direct loss that could be proven is the amount of a license fee. An award

of such an amount would be an invitation to infringe with no risk to the

infringer.

26

Based on these considerations, the Register concluded that the princi-

ple of statutory damages appropriately serves to assure adequate compen-

L.J

. 407, 412-13 (1941). Radio royalties comprised about two-thirds of AS-

CAP revenues at that time.

24

See

W

ILLIAM

S. S

TRAUSS

, S

TUDY

N

O

. 22, T

HE

D

AMAGE

P

ROVISIONS OF THE

C

OPYRIGHT

L

AW

, (1956)

, reprinted in 1

O

MNIBUS

C

OPYRIGHT

R

EVISION

L

EGISLATIVE

H

ISTORY

,

at ix-32 (George S. Grossman ed., 2001) (summariz-

ing the development of copyright damages law through the 1909 Act); see

also Stephanie Berg, Remedying the Statutory Damages Remedy for Secon-

dary Copyright Infringement Liability: Balancing Copyright and Innovation

in the Digital Age, 56 J.

C

OPYRIGHT

S

OC

’

Y

265 (2009).

25

See

U.S. C

OPYRIGHT

O

FFICE

, R

EPORT OF THE

R

EGISTER OF

C

OPYRIGHTS ON

THE

G

ENERAL

R

EVISION OF THE

U.S. C

OPYRIGHT

L

AW

102 (July 1961)

[hereinafter cited as “Register’s 1961 Report”].

26

See id.

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 13 1-MAY-14 10:19

This American Copyright Life 213

sation for harm and “to deter infringement.”

27

The Register further

explained that:

the courts should, as they do now, have discretion to assess statutory

damages in any sum within the minimum and maximum [ranges]. In ex-

ercising this discretion the courts may take into account the number of

works infringed, the number of infringing acts, the size of the audience

reached by the infringements, etc. But in no case should the courts be

compelled, because multiple infringements are involved, to award more

than they consider reasonable.

28

Accordingly, Congress ultimately retained, with some updating and revi-

sion, statutory damages for copyright infringement.

29

This deterrent regime worked relatively well throughout copyright

law’s long history. The risk of incurring large fines channeled restaurants,

27

See id. at 103.

28

See id. at 105.

29

See Copyright Act of 1976, Pub. L. No. 94-553, 90 Stat. 2541 (codified at 17

U.S.C. § 504). The 1976 Act provided that:

(c) Statutory Damages.

(1) Except as provided by clause (2) of this subsection, the copyright

owner may elect, at any time before final judgment is rendered, to

recover, instead of actual damages and profits, an award of statutory

damages for all infringements involved in the action, with respect to

any one work, for which any one infringer is liable individually, or for

which any two or more infringers are liable jointly and severally, in a

sum of not less than $250 or more than $10,000 as the court considers

just. For the purposes of this subjection, all the parts of a compilation

or derivative work constitute one work.

(2) In case where the copyright owner sustains the burden of prov-

ing, and the court finds, that infringement was committed willfully,

the court in its discretion may increase the award of statutory dam-

ages to a sum of not more than $50,000. In a case where the infringer

sustains the burden of proving, and the court finds, that such infringer

was not aware and had no reason to believe that his or her acts con-

stituted an infringement of copyright, the court it its discretion may

reduce the award of statutory damages to a sum of not less than $100.

The court shall remit statutory damages in any case where an in-

fringer believed and had reasonable grounds for believing that his or

her use of the copyrighted work was a fair use under section 107, if

the infringer was: (i) an employee or agent of a nonprofit educational

institution, library, or archives acting within the scope of his or her

employment who, or such institution, library, or archives itself, which

infringed by reproducing the work in copies or phonorecords; or (ii) a

public broadcasting entity which or a person who, as a regular part of

the nonprofit activities of a public broadcasting entity (as defined in

subsection (g) of section 118) infringed by performing a published

nondramatic literary work or by reproducing a transmission program

embodying a performance of such a work.

17 U.S.C. § 504 (1976).

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 14 1-MAY-14 10:19

214 Journal, Copyright Society of the U.S.A.

bars, dance halls and other establishments publicly performing copy-

righted works into licensing arrangements with the collecting societies. It

also discouraged commercial infringement enterprises. The problem of

non-commercial infringement rarely arose because of the inherent difficul-

ties of reproducing high quality copies of records, books, and films and

finding scalable commercial outlets for counterfeit goods in the analog

age. Copyright industries rarely if ever needed to pursue consumers for

copyright infringement. For these reasons, the deterrent damages regime

tempered by judicial discretion garnered broad support in the delibera-

tions over the 1976 Act and did not galvanize significant public opposition

before the Internet Age.

Serious concerns about record piracy would not emerge until the ad-

vent of home taping equipment in the 1970s.

30

As “My Generation”

learned, vinyl was a successful technological protection measure.

31

Reel

to reel decks were cumbersome and even a high quality Teac

™

cassette

deck introduced substantial distortion. And copies of copies were awful.

Tape piracy simply did not scale. The main usage of home taping was for

music portability — car stereos and the Sony Walkman, which did not

reach the market until 1980.

B. The Gathering Digital Copyright Storm

Copyright enforcement would become a more salient issue shortly af-

ter I graduated from high school as a result of a startling new consumer

technology: the video cassette recorder (VCR).

32

The Sony Betamax

would for the first time allow consumers to record a show on one channel

while they watched a show on another. Instead of embracing the VCR,

30

The British Phonographic Industry launched an anti-infringement campaign in

the 1980s with the slogan “Home Taping Is Killing Music.” See Home Tap-

ing Is Killing Music,

W

IKIPEDIA

,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Home_Taping

_Is_Killing_Music (last visited Nov. 4, 2013). The logo portrayed a cassette-

shaped skull and cross bones with the words “And It’s Illegal.” It is unclear

whether the campaign discouraged home taping, but it did generate some

amusing ridicule. The Dead Kennedys left the back side of their “In God

We Trust Inc.” cassette blank. The caption read: “Home taping is killing

record industry profits! We left this side blank so you can help.” Other

parodies included: “Home Sewing Is Killing Fashion” and “Home Taping Is

Killing the Music Industry, and It’s Fun.”

31

See Peter S. Menell, Envisioning Copyright Law’s Digital Future, 46

N.Y.L.

S

CH

. L. R

EV

. 63, 103-06 (2002).

32

See generally Peter S. Menell & David Nimmer, Unwinding Sony, 95

C

AL

. L.

R

EV

.

941 (2007) (chronicling the litigation over the VCR). Tensions be-

tween the technology and content were playing out within Washington cir-

cles, see, e.g.,

N

AT

’

L

C

OMM

’

NON

N

EW

T

ECHNOLOGICAL

U

SES OF

C

OPYRIGHTED

W

ORKS

, F

INAL

R

EPORT

(1978) (photocopying and com-

puters), but those debates were far removed from average consumers.

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 15 1-MAY-14 10:19

This American Copyright Life 215

Universal Studios became concerned about how this new consumer tech-

nology might affect one of its technology business ventures — a multi-

million dollar, but still nascent, investment in videodisc technology. Vide-

odisc promised to create a market for pre-recorded video content, much

like phonorecords. As conceived at the time, however, videodisc technol-

ogy would not have recording capability.

As a result, Universal sought to persuade Sony, with whom it had

other business dealings, to drop its VCR business plans. When Sony de-

clined, Universal sued for copyright infringement with the support of

much of Hollywood. The litigation, which would drag on for eight years

and two arguments to the Supreme Court, raised serious questions for the

public over Hollywood’s exertion of power over consumer electronics in-

novators and the consuming public. The ultimate resolution — rejecting

Universal’s lawsuit — quelled public concerns and the copyright system

once again faded from public consciousness.

Such concerns would surface again surrounding the introduction of

Digital Audio Tape (DAT) technology into the United States in the late

1980s. I had just finished my clerkship with Judge Newman and was em-

barking on an academic career when the Office of Technology Assessment

(OTA), a research arm of the U.S. Congress, invited me to serve on the

Copyright and Home Copying Advisory Panel.

33

Our charge was to study

the prevalence of home copying of copyrighted works and to assess policy

options. A consumer survey conducted for our panel in 1988 determined

that approximately 40% of Americans over the age of 10 had taped re-

corded music in the past year — principally for the purpose of “space

shifting” (listening to compact discs on car cassette players). Most of

those surveyed considered this to be an acceptable behavior. Although

music copyright owners expressed concern about the prevalence of home

taping and that the introduction of DAT technology into the United States

would result in rampant piracy, concerns subsided with the passage of the

Audio Home Recording Act (AHRA)

34

a short time later. This legisla-

tion largely insulated consumers from liability while requiring modest

technological restrictions on devices and providing for new revenue

streams for copyright owners (levies on media and devices). When the

DAT format failed to gain favor in the commercial marketplace, the rela-

tively low level public expressions of concern subsided.

Ongoing advances in computer technology combined with the rollout

of the Internet in the early to mid 1990s gradually raised tensions over

copyright policy. Much of the debate, however, took place in international

33

U.S. C

ONGRESS

, O

FFICE OF

T

ECH

. A

SSESSMENT

, C

OPYRIGHT AND

H

OME

C

OP-

YING

: T

ECHNOLOGY

C

HALLENGES THE

L

AW

, OTA-CIT-422 (1989)

34

See Pub. L. No. 102-563, 106 Stat. 4237 (1992) (codified at 17 U.S.C.

§§ 1001–10).

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 16 1-MAY-14 10:19

216 Journal, Copyright Society of the U.S.A.

fora and among the cognoscenti — content industry organizations, con-

sumer electronics manufacturers, and a nascent group of digital media and

Internet companies and coalitions.

After the unsuccessful 1994 criminal prosecution of David

LaMacchia, an MIT student who had allegedly facilitated massive piracy

by operating a free online bulletin board service widely used for sharing

copyrighted computer software and videogames, Congress enacted the No

Electronic Theft (NET) Act in 1997.

35

The NET Act expanded criminal

copyright infringement to encompass receipt (or expectation of receipt) of

anything of value, including other copyrighted works, and reproduction or

distribution in any 180-day period of copyrighted works with a total retail

value of more than $1,000. In addition, the NET Act ramped up penalties.

The House Report highlighted the economic and employment costs of

software piracy to the software industry and the expanded piracy threats

posed by the Internet.

36

Congressional hearings emphasized the need to

confront the non-economic motivations of self-aggrandizing “Robin

Hood”-like computer hackers.

37

The NET Act passed without attracting

much public attention outside of a relatively small circle of computer

scientists.

C. The Perfect Copyright Storm

The legislative sentiments expressed during the NET Act delibera-

tions in combination with new copyright legislation and a surprising Su-

preme Court decision would soon create conditions for the “Perfect

(Copyright) Storm.”

38

35

No Electronic Theft (NET) Act, Pub. L. No. 105-147, 111 Stat. 2678 (1997); see

Eric Goldman, A Road to No Warez: The No Electronic Theft Act and

Criminal Copyright Infringement, 82

O

R

. L. R

EV

. 369, 373-77 (2003).

36

See

H.R. R

EP

. N

O

. 105-339, at 4 (1997); see also Rep. Howard Coble, The

Spring 1998 Horace S. Manges Lecture – The 105th Congress: Recent Devel-

opments in Intellectual Property Law, 22

C

OLUM

.-VLA J.L. & A

RTS

269

(1998) (reprinting the House Report with some additional commentary by

Rep. Coble).

37

See 143 Cong. Rec. S12,689, S12,691 (daily ed. Nov. 13, 1997) (statement of

Sen. Kyl) (targeting software pirates who seek notoriety instead of money);

143 Cong. Rec. H9883, H9886 (daily ed. Nov. 4, 1997) (statement of Rep.

Cannon) (targeting “Robin Hood” types); 143 Cong. Rec. H9883, H9885

(daily ed. Nov. 4, 1997) (statement of Rep. Frank) (the Act aims at “seri-

ously maladjusted” individuals who infringe not for profit but to show their

smarts and get attention).

38

I borrowed the title from the infamous Halloween Nor’easter of 1991 — the

confluence of a seasonal North Atlantic storm system that combined with

Hurricane Grace to bring about a devastating storm off the New England

coast. Sebastian Junger’s best-selling novel, The Perfect Storm (1997),

chronicled the destruction of the Andrea Gail and loss of its fishing crew.

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 17 1-MAY-14 10:19

This American Copyright Life 217

Copyright lobbyists were hard at work in the early to mid-1990s lay-

ing the groundwork for a new copyright regime for the digital age. Presi-

dent Clinton established the Information Infrastructure Task Force

(“IITF”) in 1993 to develop a comprehensive framework. The IITF pro-

duced a “white paper” calling for strengthening copyright protections and

prohibiting circumvention of technological protection measures put in

place by copyright owners.

39

The nascent ISP industry organized opposi-

tion to the draft 1995 legislation, resulting in the bills stalling in committee.

The Clinton Administration took its proposals to the World Intellectual

Property Organization’s (WIPO) diplomatic conference the following

year. A compromise was achieved with negotiators agreeing to the anti-

circumvention provision in conjunction with safe harbors for Internet ser-

vice providers (ISPs).

40

Congress would implement the WIPO copyright

treaties in the Digital Millennium Copyright Act of 1998 (DMCA).

41

Meanwhile, in a decision driven by forces unrelated to the digital age

that would significantly affect digital copyright enforcement, the Supreme

Court ruled in Feltner v. Columbia Pictures Television, Inc.

42

that the Sev-

enth Amendment required that the determination of statutory damages

fall within the province of the jury in copyright cases in which a party had

requested a jury trial. This had the practical effect of thwarting Congress’s

intent to have experienced jurists exercise discretion in awarding statutory

damages

43

and increasing the uncertainty surrounding statutory damage

awards. Congress would compound this effect by enacting the Digital

Theft Deterrence and Copyright Damages Improvement Act of 1999,

44

ramping up the statutory damage range to $30,000 per infringed work and

up to $150,000 per infringed work for willful infringement.

These developments set the stage for the “Perfect Copyright Storm”

— a strong deterrent copyright regime with potentially massive civil penal-

ties administered by lay jurists, expanded criminal liability, and new and

untested safe harbors. The storm’s catalyst came from rapid advances in

digital and Internet technology and broadband rollout.

George Clooney and Mark Wahlberg would star in Warner Bros.’s 2000

dramatization of the story. The film’s release coincided with copyright law’s

perfect storm.

39

See IPNII White Paper, supra note 10; cf. Pamela Samuelson, The Copyright

Grab,

W

IRED

(Jan. 1996), http://www.wired.com/wired/archive/4.01/white

.paper_pr.html.

40

See WIPO Copyright Treaty, Dec. 20, 1996,

S. T

REATY

D

OC

. N

O

. 105-17, 36

I.L.M. 65 (1997); WIPO Performances and Phonograms Treaty, Dec. 20,

1996,

S. T

REATY

D

OC

. N

O

.

105-17, 36 I.L.M. 76 (1997).

41

Pub. L. No. 105-304, 112 Stat. 2860.

42

523 U.S. 340 (1998).

43

See Register’s 1961 Report, supra note 25, at 105.

44

Pub. L. No. 106-160, 113 Stat. 1774.

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 18 1-MAY-14 10:19

218 Journal, Copyright Society of the U.S.A.

The Internet storm struck with unprecedented ferocity in mid 1999.

45

Napster’s peer-to-peer file sharing service captivated America’s youth,

providing nearly instantaneous, convenient, and free access to an unprece-

dented collective archive. Anyone with a computer and access to the In-

ternet could share and access just about any sound recording. Prior to

Napster, the Internet was a useful curiosity. After Napster, the Internet

was exciting. For that reason, I view Napster’s arrival as the birth of the

digital copyright. Peer-to-peer technology would quickly encompass all

manner of works of authorship.

The perfect copyright storm would unfold over more than a decade as

copyright owners sought to protect their works amidst the battering waves

of a dynamic of promiscuous distribution platforms unlike anything seen

before or anticipated. As bandwidth, storage capacity, and computer

speed continued to improve, the challenges of enforcing copyright law

continued to grow.

46

All of the storm planning that went into the WIPO

Copyright Treaties, the DMCA, and ramping up of statutory damages did

little to prepare netizens, online service providers, and copyright owners

for the onslaught. The storm surge knocked out much of the music copy-

right system in one fell swoop. The next decade would reveal many in-

sights about the interplay of copyright enforcement and public perceptions

of the copyright system.

D. The Digital Copyright Enforcement Saga

Most of my students found file-sharing both irresistible and wonder-

ful. Professor Lawrence Lessig warned of content owners locking down

the Internet and freedom of expression.

47

Several other scholars called

upon Congress to establish compulsory licenses for file-sharing.

48

Hollywood looked to invoke copyright law’s deterrence regime and to

cash in on its investments in stronger remedies. Napster sought to test the

DMCA’s online service provider safe harbor and Sony’s staple article of

commerce doctrine.

The Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) won the ini-

tial battle, resulting in Napster’s demise by July 2001. But the war was

45

See Napster,

W

IKIPEDIA

,

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Napster (last visited Nov.

4, 2013).

46

See Menell, supra note 31.

47

See

L

AWRENCE

L

ESSIG

, T

HE

F

UTURE OF

I

DEAS

: T

HE

F

ATE OF THE

C

OMMONS

IN A

C

ONNECTED

W

ORLD

200 (2001).

48

See

W

ILLIAM

W. F

ISHER

III, P

ROMISES

T

O

K

EEP

: T

ECHNOLOGY

, L

AW

,

AND

THE

F

UTURE OF

E

NTERTAINMENT

(2004); Neil Weinstock Netanel, Impose a

Noncommercial Use Levy to Allow Free Peer-to-Peer File Sharing, 17

H

ARV

. J.L. & T

ECH

. 1 (2003).

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 19 1-MAY-14 10:19

This American Copyright Life 219

only just beginning as more versatile file-sharing networks had emerged.

49

Of perhaps greater import, the RIAA was suffering heavy casualties in the

court of public opinion. Their most effective spokespersons — recording

artists — were divided

50

and angered by record labels’ latest machinations

to undermine their interests.

51

The litigation between the RIAA and Nap-

ster produced a steady flow of news reports fanning the flames of discon-

tent over the recording industry’s enforcement efforts.

52

Most file-sharers did not perceive their actions to be immoral.

53

Even

those netizens who recognized that file-sharing treated artists unfairly

49

See Brad King, While Napster Was Sleeping,

W

IRED

(Jul. 24, 2001), http://www

.wired.com/news/mp3/1,1285,45480,00.html (noting that “Napster’s chief ri-

vals — Kazaa, Bearshare, Audiogalaxy and iMesh — have seen significant

upswings in their traffic”).

50

See Courtney Love, Courtney Love Does the Math: The Controversial Singer

Takes on Record Label Profits, Napster and “Sucka VCs”,

S

ALON

(Jun. 14,

2000), http://www.salon.com/2000/06/14/love_7; Janis Ian, The Internet De-

bacle – An Alternative View,

P

ERFORMING

S

ONGWRITER

M

AGAZINE

(May

2002), http://www.janisian.com/reading/internet.php; John Borland, Rapper

Chuck D Throws Weight Behind Napster,

C—

NET

(May 1, 2000) (seeing

Napster as a unique promotional tool for lesser known artists), http://news

.com/2100-1023-239917.html.

51

See David Nimmer & Peter S. Menell, Sound Recordings, Works For Hire, and

the Termination-of-Transfers Time Bomb, 49

J. C

OPYRIGHT

S

OC

’

Y

387, 388-

93 (2001) (chronicling the RIAA’s backroom deal-making that resulted in a

“technical amendment” to the Copyright Act cutting off recording artists’

right to terminate transfers of copyrights; and the decision to rescind the

amendment when it came to light just as Napster emerged and labels

needed artists’ support); Lital Helman, When Your Recording Agency

Turns into an Agency Problem: The True Nature of the Peer-to-Peer Debate,

50 IDEA 49, 51 (2009) (observing that “the anti-file-sharing course adopted

by the music industry is best understood as an agent-principal problem. It is

aimed at strengthening the control for the agents, namely the record com-

panies’ control over the market, to the detriment of the principals, namely

the artists.”); Note, Exploitative Publishers, Untrustworthy Systems, and the

Dream of a Digital Revolution for Artists, 114

H

ARV

. L. R

EV

. 2438 (2001)

(highlighting the historic subjugation of creators by publishers and record

labels).

52

See Declan McCullagh, Napster’s Million Download March,

W

IRED

N

EWS

(Mar. 28, 2001); http:// www.wired.com/news/politics/0,1283,42676,00.html

Amy Harmon, Napster Users Mourn End of Free Music,

N.Y. T

IMES

, Nov.

1, 2000, at C1; Amy Harmon, The Napster Decision: The Reaction; Napster

Users Make Plans for the Day the Free Music Dies, N.Y.

T

IMES

, Feb. 12,

2001, at C1; Amy Harmon, Online Davids vs. Corporate Goliaths, N.Y.

T

IMES

(Aug. 6, 2000), http://www.nytimes.com/library/review/080600nap

ster-review.html; Declan McCullagh, Digital Copyright Law on Trial,

W

IRED

N

EWS

(Jan. 18, 2000), at http://www.wired.com/news/politics/o,1283

,33716,00.html.

53

See Ram D. Gopal, & G. Lawrence Sanders, Digital Music and Online Sharing:

Software Piracy 2.0?, 46

C

OMM

.

OF THE

ACM

107, 116 (2003) (finding “no

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 20 1-MAY-14 10:19

220 Journal, Copyright Society of the U.S.A.

wondered why the recording industry was unable to roll-out user-friendly

authorized music websites. Although the major record labels had been

planning their own online music stores before Napster’s emergence,

54

their efforts lacked the variety, functionality, and flexibility of peer-to-

peer networks.

55

By the time that the major labels opened their catalogs

up to Apple’s iTunes Music Store in April 2003,

56

many music fans had

become accustomed to file-sharing.

Soon after Napster’s demise, the RIAA targeted the next wave of file-

sharing services — Grokster, Morpheus, and KaZaA — filing suit in the

Central District of California in October 2001. In April 2003, Judge Ste-

phen Wilson held that even though these defendants “may have intention-

ally structured their business to avoid secondary liability for copyright

infringement, while benefitting from the illicit draw of their wares,” they

nonetheless fell within the Sony staple of commerce safe harbor because

their file-sharing services were capable of substantial non-infringing use.

57

The RIAA vowed to appeal Judge Wilson’s decision, but an appeal could

take years and might well result in the judgment being affirmed. Thus, the

RIAA faced a difficult decision — whether to sue file-sharers.

58

Like many intellectual property scholars, I was thrust into public de-

bate over these difficult issues. I had been invited to prepare a paper on

the question “Can Our Current Conception of Copyright Law Survive the

Internet Age?” in honor of the Honorable Jon O. Newman, the judge for

whom I had clerked, at the celebration of his thirty years on the Federal

bench.

59

I was invited to moderate a panel at the April 2002 Computers,

Freedom & Privacy (CFP) Conference on “Copyright and Innovation: The

significant deterrent effect on music piracy through legal and education

campaigns”); John Leland, Praise God and Pass the Music Files,

N.Y. T

IMES

(Apr. 25, 2004), http://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/25/weekinreview/ideas-

trends-praise-god-and-pass-the-music-files.html (quoting a Christian rock

music downloader opining: “[i]f the money went into the artist’s pocket, I’d

have more of a dilemma. But the companies make enough money.”); Geof-

frey Neri, Note: Sticky Fingers or Sticky Norms? Unauthorized Music

Downloading and Unsettled Social Norms, 93

G

EO

. L.J

. 733, 742 (2005).

54

See infra text accompanying notes 161–63.

55

See Menell, supra note 31, at 172-73.

56

See iTunes Store,

W

IKIPEDIA

, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ITunes_Store.

57

See Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios, Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd., 259 F. Supp. 2d

1029, 1046 (C.D. Cal. 2003).

58

See Justin Hughes, On the Logic of Suing One’s Customers and the Dilemma of

Infringement-Based Business Models, 22

C

ARDOZO

A

RTS

& E

NT

. L.J. 725

(2005).

59

See Symposium – Judge Jon O. Newman: A Symposium Celebrating His Thirty

Years on the Federal Bench and an Occasion to Reflect on the Future of

Copyright, Federal Jurisdiction, and International Law Symposium, 46

N.Y.L. S

CH

. L. R

EV

.

1 (2002-2003).

\\jciprod01\productn\C\CPY\61-2\CPY202.txt unknown Seq: 21 1-MAY-14 10:19

This American Copyright Life 221

P2P Experience.”

60

And perhaps most challenging of all, my older son

Dylan, who was nearing his twelfth birthday, couldn’t understand why I

was not as enthusiastic as he and his friends about file-sharing technology.

Did I not support his love of technology and music? Of course I did, but I

also worried about incentives for the next generations of creators — in-

cluding him. Let’s just say that this was not the response he was looking

for.

Whereas many in the academy had quickly taken sides and formu-

lated solutions, I was genuinely conflicted about the larger policy issues.

The Internet was developing rapidly and I did not feel that we had enough

information about the interplay of the Internet and creative ecosystems to

make definitive judgments about the proper course. It would take some

time to see how the online marketplace responded. My hope was that

competition and technological advance would bring about a balanced solu-

tion, but it was clear that competing with free was complicating the task of

start-ups, like emusic.com, to gain a foothold while pushing the major la-

bels to explore licensing. I was teaching a course on intellectual property

in the entertainment industries and was disheartened by the changes un-

folding in the Bay Area music community. My colleagues working in the

music field were moving to other pursuits as funding for “baby bands”

dried up. I had started an annual conference on “Digital Music” at the

Berkeley Center for Law & Technology and was dismayed by the deep

and growing rifts between Silicon Valley and Hollywood, labels and artists,