Use of force by the

Toronto Police Service

Final report

Dr. Scot Wortley, PhD, Associate Professor

Centre of Criminology and Sociolegal Studies,

University of Toronto

Dr. Ayobami Laniyonu, PhD, Assistant Professor

Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies,

University of Toronto

Erick Laming, Doctoral Candidate

Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies,

University of Toronto

Use of force by the

Toronto Police Service

Final report

Dr. Scot Wortley, PhD, Associate Professor

Centre of Criminology and Sociolegal Studies,

University of Toronto

Dr. Ayobami Laniyonu, PhD, Assistant Professor

Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies

University of Toronto

Erick Laming, Doctoral Candidate

Centre for Criminology and Sociolegal Studies,

University of Toronto

Submitted to the Ontario Human Rights Commission: July 2020

ISBN: 978-1-4868-4617-7 PRINT

978-1-4868-4618-4 PDF

© 2020, Government of Ontario

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

1

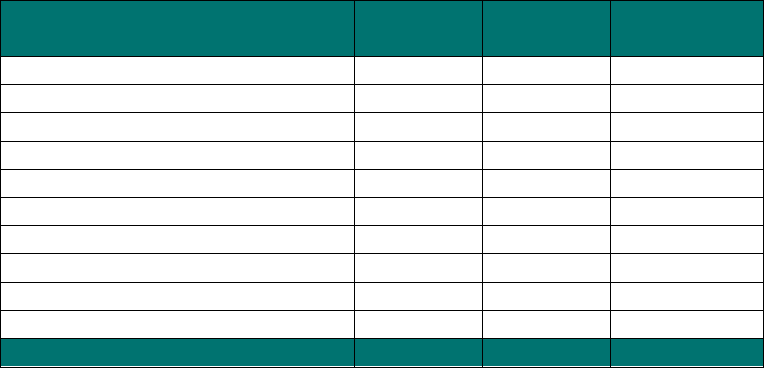

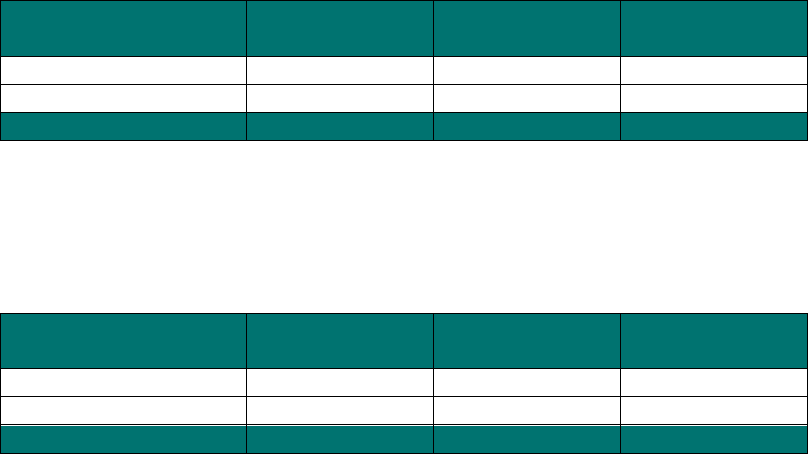

Contents

Introduction ............................................................................................................................ 3

Part A: ....................................................................................................................................... 5

Literature review: race and police use of force .................................................................. 5

Race and use of force: American research ................................................................................ 8

Race and use of force: Canadian research ................................................................................ 9

Racial disparity in context.......................................................................................................... 12

The results of multivariate analyses ........................................................................................ 22

Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 26

Part B: Community perceptions of racial bias .................................................................. 29

Part C: An examination of Special Investigations Unit cases involving

the Toronto Police Service .............................................................................................. 34

Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 34

Methodology ............................................................................................................................... 35

Measuring racial disparity ......................................................................................................... 38

Findings ....................................................................................................................................... 40

The impact of sex ....................................................................................................................... 41

Cause of civilian injury ............................................................................................................... 44

Civilian injury not caused by police .......................................................................................... 46

Civilian injury caused by police-involved traffic accidents ..................................................... 46

Sexual assault cases ................................................................................................................... 47

Police use of force cases ............................................................................................................ 52

Police shooting cases ................................................................................................................. 56

Police use of force cases that resulted in civilian death ........................................................ 57

Police shooting deaths ............................................................................................................... 59

The context of police use of force ...................................................................................... 62

Civilian behaviour at time of use of force encounter

............................................................. 62

Possession of a weapon ............................................................................................................ 64

Possession of a weapon during police shootings ................................................................... 67

Civilian criminal history at time of police use of force incidents .......................................... 68

Civilian mental health at time of police use of force incidents ............................................. 69

Civilian impairment at time of police encounter .................................................................... 71

Type of police contact ................................................................................................................ 72

Community-level crime rates .................................................................................................... 74

Outcomes of SIU investigations ................................................................................................ 78

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

2

Problems with police cooperation ........................................................................................... 80

Toronto-American comparisons ............................................................................................... 82

Summary ..................................................................................................................................... 84

Part D: An analysis of TPS “lower-level” use of force cases ............................................. 86

Coders’ process of identifying and coding lower-level use of force cases ......................... 88

Findings ....................................................................................................................................... 90

Representation in TPS use of force reports ............................................................................ 93

Type of force used by TPS officers ........................................................................................... 94

Type of civilian injury ................................................................................................................. 96

Involvement of paramedics ....................................................................................................... 97

Location of civilian medical treatment ..................................................................................... 98

Nature of police contact ............................................................................................................ 99

Civilian behaviour during use of force incident .................................................................... 101

Civilian weapons ....................................................................................................................... 102

How civilian weapon identified ............................................................................................... 103

Civilian arrests .......................................................................................................................... 104

Fled police custody ................................................................................................................... 105

Resisting arrest charges........................................................................................................... 106

Civilian criminal record ............................................................................................................ 107

Civilian substance use .............................................................................................................. 107

Civilian mental health .............................................................................................................. 109

Community-level crime rates .................................................................................................. 110

Summary ................................................................................................................................... 112

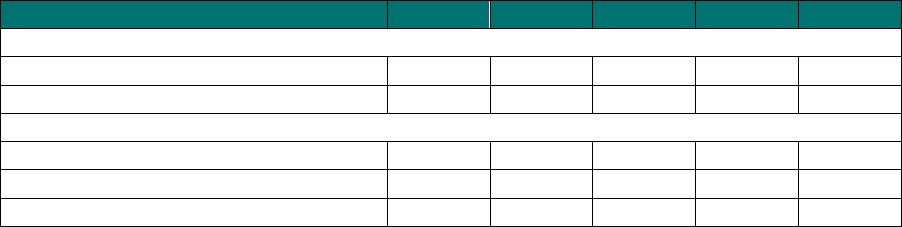

Part E – Multivariate analysis of use of force cases ....................................................... 116

Introduction .............................................................................................................................. 116

The data

Variables .................................................................................................................................... 117

Results ....................................................................................................................................... 118

Results from models that exclude patrol zones 51 and 52 ................................................. 122

Conclusion and limitations ...................................................................................................... 124

Part F: Explaining Black over-representation in police use of force statistics .......... 126

Explanatory models ................................................................................................................. 130

Conclusion ................................................................................................................................. 136

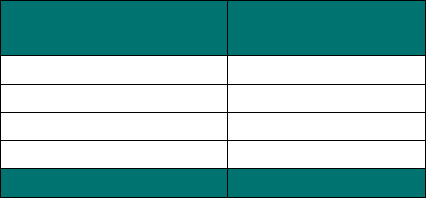

Appendix A: SIU case template: 2013 – 2017 data

.......................................................... 140

Appendix B: Lower-level use of force data collection template ................................... 151

References ........................................................................................................................... 170

..................................................................................................................................... 117

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

3

Introduction

Police use of force against Black people has emerged as one of the most controversial

issues facing the law enforcement community in North America. In the United States, high-

profile use of force incidents – including the cases of Rodney King, Abner Louima, Amadou

Diallo, Timothy Thomas, Arthur McDuffie, Freddie Grey, Eric Garner, Michael Brown, Tamir

Rice, Philando Castille, Ataliana Jefferson, Breonna Taylor and George Floyd – serve to increase

tensions between the Black community and the police and solidify perceptions that the police

are racially biased (Walker 2005; Walker et al. 2004; Joseph et al. 2003). The negative impact of

police violence on community cohesion can be profound. For example, over the past 30 years,

specific incidents of police violence against Black civilians have sparked major urban riots in

several American cities including Ferguson (Missouri), Miami (Florida), Cincinnati (Ohio), Los

Angeles (California) and New York City (New York). Allegations of police brutality against people

of African descent have also directly contributed to large-scale urban unrest in both France and

England (Kawalerowicz et al. 2015).

As in the United States and Europe, police use of force against Black, Indigenous and other

minority civilians has emerged as a controversial issue in Canada. Over the past few decades,

well publicized police use of force cases in both Ontario and Quebec – including the cases of

Dudley George, Lester Donaldson, Allen Gosset, Sophia Cook, Buddy Evans, Jeffrey Reodica,

Wade Lawson, Marlon Neal, Eric Osawe, Michael Elgin, Ozama Shaw, Tommy Barnett,

Raymond Lawrence, Sammy Yatim, Pierre Coriolan, Jermaine Carby, Andrew Loku, Abdirahman

Abdi, Olando Brown, Dafonte Miller, D’Andre Campbell and Ejaz Choudry – have led to

community allegations of police discrimination, demonstrations, urban unrest and the rise of

the “Black Lives Matter” social movement.

Police use of force is a crucially important issue. It directly engages with issues of public

safety and the safety of law enforcement officers. However, when done improperly, police

use of force can cause the unnecessary death or serious injury of civilians, undermine public

trust in the police and compromise the legitimacy of the entire criminal justice system. Finally,

police use of force can erode social cohesion and contribute to radicalization, riots and other

social control issues. Unfortunately, despite its importance, police use of force has been

subject to surprisingly little empirical research – especially in the Canadian context. The

following report attempts to address this gap. The authors of this report were retained by the

Ontario Human Rights Commission (OHRC) to examine a sample of use of force cases involving

the Toronto Police Service (TPS) – Canada’s largest municipal law enforcement agency. Details

about this sample are provided in the methodology section.

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

4

The report is divided into six sections. Part A provides a review of previous academic

research on police use of force conducted in both the United States and Canada. Part B

explores public perceptions of police use of force, against the Black community, using

data from two surveys of Toronto residents. Part C examines TPS use of force cases that

resulted in the death or serious injury of civilians. The data for this analysis was derived

from the Ontario government’s Special Investigations Unit (SIU). Part D examines data on

“less serious,” lower-level use of force cases derived from internal TPS records. These are

cases that allegedly did not meet the injury threshold needed to trigger a SIU investigation.

Part E presents a variety of multivariate statistical models designed to examine the impact

of race on police use of force incidents after controlling for other theoretically relevant,

patrol zone-level variables. The final section of the report (Part F) summarizes major results

and presents a variety of explanatory models that might help explain the over-representation

of Black people in Toronto police use of force statistics. These explanatory models may help

guide future policy development.

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

5

Part A:

Literature review: race and police use of force

Both Canadian and American experts have identified that there is a dearth of high-quality

data on police use of force cases. During a 2015 speech, James B. Comey, the former

Director for the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), clearly articulated the extreme

challenges associated with conducting research on police use of force. Director Comey

stated that:

Not long after riots broke out in Ferguson late last summer, I asked my staff to

tell me how many people shot by police were African American in this country.

I wanted to see trends. I wanted to see information. They couldn’t give it to me,

and it wasn’t their fault. Demographic data regarding officer-involved shootings

is not consistently reported to us through our Uniform Crime Reporting Program.

Because reporting is voluntary, our data is incomplete and therefore, in the

aggregate, unreliable (Comey, 2015, paras 32-33).

The fact that in 2015, America’s top cop could not easily assess up-to-date, accurate

information on police use of force is both surprising and troubling. The failure to create

a national police use of force database, is an issue that exists in the United States and

Canada as well as many other Western nations (see Zimring 2017). Interestingly, most

developed nations consistently generate reliable national statistics on both minor and

serious criminal activity – including minor theft, car theft, physical assaults and burglaries.

It is therefore disappointing that similar data collection practices have not been used to

produce accurate, reliable statistics on police use of force – including information on cases

that involve the death or serious injury of civilians.

The lack of quality use of force data is a long-standing issue. In 1931, after confirming

allegations of widespread police brutality across the United States, the Wickersham

Commission recommended that all police agencies collect data on police use of force

incidents (Shane, 2016). Since then, several other American commissions and inquiries

have noted the poor quality of police use of force statistics and called for improved data

collection practices. For example, the 2015 President’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing

argued that: “policies on use of force should require agencies to collect, maintain, and

report data to the Federal Government on all officer-involved shootings, whether fatal or

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

6

non-fatal, as well as any in-custody death” (cited in Shane, 2016: p. 3). Unfortunately, this

recommendation has not yet been translated into policy. In other words, U.S. law enforcement

agencies are still not legally required to report details about use of force incidents.

Zimring (2017) examines three U.S efforts to collect national data on police killings of civilians:

1) the National Vital Statistics System (NVSS); 2) the Uniform Crime Report’s Supplemental

Homicide Reporting System (which documents “justifiable homicides” involving police officers);

and 3) the Bureau of Justice Statistics Arrest-Related Deaths Program. Drawing on insights from

an FBI data quality exercise, along with information from crowd-sourced and media-compiled

datasets, Zimring (2017) argues that the U.S. government typically undercounts the true

number of police killing by more than half. While government statistics estimate that the

annual number of civilians killed by police in the United States is approximately 500, the true

figure appears to be closer to 1,000 (Zimring, 2017).

This gap emerges because the reporting of police killings – let alone less serious use of force

incidents – is only voluntary. Some services provide data on all incidents, others provide data

on only some incidents, while others provide no data at all. Zimring also questions the validity

and completeness of the police data that is provided to federal agencies and laments that

there are no data quality assurance checks. He notes that some police services may not want

to provide information that could cause reputational damage or challenge the legitimacy of

officers’ use of force decision-making (see also Ross 2015; Nix 2017; Williams et al. 2016). In

other words, even when data is provided by American police services, there are concerns that

it is often incomplete and/or inaccurate.

The data situation in Canada is even worse than the United States. Currently there is no

Canadian effort – voluntary or otherwise – to create a national database on police killings

or other police use of force incidents. Statistics Canada only tracks cases involving the very

small number of police officers who have been criminally charged with killing a civilian (Gillis,

2015). As a general practice, local police agencies in Canada also do not release official

statistics on use of force cases (Carmichael & Kent, 2015; Wortley, 2006). Furthermore, the

methodologies used to collect use of force data vary greatly between jurisdictions (Kiedrowski

et al., 2015). In 2015, to counter these limitations, a Federal/Provincial/Territorial Use of Force

Working Group was given the mandate to share information on use of force reporting policies

and practices with the goal of improving the quality of Canadian use of force data (Kiedrowski

et al., 2015). However, this working group has yet to materialize and no apparent progress has

been made in establishing a national database on police use of force in Canada.

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

7

For many years, both researchers and community advocates have been arguing for better

data collection and reporting on police use of force incidents (see Royal Commission on

the Donald Marshall, Jr. Prosecution 1989; Commission on Systemic Racism in the Ontario

Criminal Justice System 1996; Foster et al. 2016; United Nations 2017). For example, Kane

(2007: 773) argues that “all police departments should adopt as a collective professional

standard the practices of (1) collecting comprehensive data on all coercive activities,

including disciplinary actions, and (2) making those data available with minimal filtering

and justification to members of the polity.” Hickman et al. (2008) note that local and

federal governments collect and report very little information about non-lethal (lower-level)

use of force cases. In the U.S., the only systematic, national-level indicator of police use of force

is the Police-Public Contact Survey (PPCS) administered by the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS).

Unfortunately, this survey may grossly underestimate the true extent of police use of force

because it excludes recently arrested and incarcerated persons (Hickman et al., 2008; Engel,

2008). Hickman et al. (2008) propose that using a Survey of Inmates in Local Jails (SILJ),

in combination with the PPCS, would provide a more sound and complete estimate of police

use of force incidents. However, they also note that the use of multiple sources can produce

data problems because of inconsistencies in collection and reporting practices (Klinger, 2008;

Williams, Bowman & Jung, 2016).

Researchers have also been vocal in highlighting that law enforcement agencies are often

uncooperative with respect to documenting use of force incidents. Smith (2008) reveals

that several attempts have been made to encourage police services to voluntarily report

use of force incidents for research and policy-development purposes. Little progress has

been made. Indeed, even when police services have been legislated to provide information

on use of force cases, resistance is common. For example, the Violent Crime Control and

Law Enforcement Act of 1994 required the Attorney General to collect data on police use

of excessive force and to publish annual reports from the data (McEwen, 1996). However,

the majority of police agencies failed to report cases of excessive force because they are

protected under the Tenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution (Hickman & Poore, 2015;

Shane, 2016). In other words, policing is the responsibility of state legislatures and the

federal government cannot mandate local police agencies to report use of force data. This

creates a significant challenge with respect to creating a national database on police use

of force. Similar obstacles exist in Canada – since policing remains the responsibility of

provincial and territorial governments.

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

8

The discussion above illustrates that, despite great public interest and policy relevance,

data collection and reporting on police use of force has been stalled, if not fiercely resisted,

by the policing community. As a result, in both the United States and Canada, research on

police killings and other use of force incidents is very limited. The research that does exist

has typically been conducted by individual researchers, special commissions of inquiry,

human rights agencies, local governments, police oversight agencies and media outlets.

Most academic researchers acknowledge the limitations of existing data and caution that

findings should be “interpreted with a grain of salt.” Others warn that, without a national

dataset, it is difficult, if not impossible, to compare use of force practices across jurisdictions or

draw broad conclusions about when the police are likely to use – or refrain from using – force

(Zimring 2017). The reader is thus advised to consider these data limitations while reviewing

the research results – on the police use of force against members of the Black community –

presented in the next section of this report.

Race and use of force: American research

Research on race and police use of force is much more prevalent in the United States than

Canada. The large racial disparities uncovered by these studies are not in dispute. Study

after study, conducted at different periods of time and in different regions of the country,

have found that African Americans are significantly over-represented in police shootings

and other cases involving police use of force (see reviews in Geller and Toch 1995; Rahtz

2003; Walker et al. 2004; Lersch and Mieczkowski 2005; Ross 2015; Zimring 2017; Menifield

et al. 2018). Importantly, research also suggests that the over-representation of African

Americans in use of force cases has declined significantly over the past 30 years. For

example, in the 1970s, American police shot and killed eight Black people for every one

White person. By 1998 that ratio had been reduced to 4:1 (see Walker 2005; Walker et al

2004). Nonetheless, by 2018, the available data suggest that Black Americans are still twice

as likely to be shot and killed by police than their White counterparts. Less is known about

other types of use of force.

Over the past several years, the Washington Post has carefully collected detailed data on all

police shooting deaths across the United States. These statistics are posted and updated

daily on their website

. In 2018, the Post recorded 992 police shooting fatalities. Twenty-

three percent of these shootings involved Black civilians, although Black people represent

only 13% of the American population. Furthermore, the Black police shooting rate (5.2 per

million) was 2.3 times greater than the White rate (2.3 per million). Findings based on the

Washington Post dataset are consistent. According to the Post, between 2015 and 2019, the

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

9

U.S. experienced between 967 and 998 police killings per year. Each year, between 22%

and 26% of all cases involved Black civilians. The rates are particularly high for Black males.

Over the past decade, studies using different local and national datasets have produced

very similar results (see Zimring 2017). It should be noted that, in approximately 10% of all

police shooting cases in the United States, the race of the civilian is listed as “unknown.”

If any of these “unknown” cases are, in fact, African American, racial disparities in police

shooting statistics could be even higher than documented by recent studies (Zimring 2017).

Finally, emerging American research further suggests that racial disparities exist with respect

to the police use of other use of force tactics – including Conducted Energy Weapons (CEWs),

pepper spray, baton use and open/closed handed techniques (see Goff et al. 2016; Crow &

Adrion, 2011; Gau et al., 2009; Lin & Jones, 2010).

Race and use of force: Canadian research

Despite growing public concern and allegations of police racial bias with respect to the use

of physical force, very little Canadian research has actually addressed this issue. Although a

growing number of studies have documented possible discrimination in other areas of the

criminal justice process – including racial differences in police surveillance practices (racial

profiling), racial differences in arrest decisions, racial differences in pre-trial outcomes and

racial differences in criminal sentencing – detailed research has yet to be conducted on

racial differences in the police use of force (see Tator and Henry 2006; Tanovich 2006;

Wortley and Marshall 2005; Wortley 2004).

Early Canadian studies were plagued by methodological issues, including small sample

sizes and a reliance on newspaper coverage of police shooting incidents. For example,

using media sources, Gabriella Pedicelli (1998) examined police shootings in Toronto

and Montreal between 1994 and 1997. She found that although Black people represented

less than 2% of Montreal’s Black population in 1991, five of the 11 people shot and killed by the

police during the study period (45%) were Black males. Similarly, although African Canadians

represented only 3.3% of Toronto’s population in 1991, six of the 12 civilians (50%) shot and

killed by the police during the study period were Black males (Pedicelli 1998: 63). A case-

by-case analysis of particularly controversial cases led Pedicelli to conclude that police officials

are often able to legitimize police violence by claiming that it is a normal reaction when

dealing with ethnic groups that are prone to “criminality” and “violence.”

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

10

Furthermore, police officer claims that they had to make “split-second decisions” during

violent, “life and death” confrontations with civilians are usually enough to have the incident

deemed a “justifiable homicide.” Police versions of shooting incidents are rarely challenged

by the media or government officials.

Phillip Stenning (1994) further explored the issue of police violence by interviewing 150

inmates from three provincial detention centers in the Greater Toronto Area. In contrast to

Pedicelli’s work, Stenning found little evidence of racial differences in experiences with police

use of force. While Black inmates were much more likely to report verbal abuse

and racial insults during arrest situations, they were not more likely to report police brutality.

However, the author cautions that these findings are far from conclusive because they are

based on interviews with a small, non-random sample of prison inmates. Indeed, only 51 Black

inmates were interviewed as part of this study. Furthermore, this study did not examine racial

differences in the use of deadly force or police violence that led to serious injury.

A 2006 study, conducted on behalf of the Ipperwash Inquiry, examined police use of force

cases documented by Ontario’s Special Investigations Unit. This study revealed that both

Black and Indigenous people were highly over-represented in Ontario police use of force

cases (Wortley 2006). By contrast, White people and members of other racial groups –

including South Asians and Asians – were significantly under-represented. The SIU

is a

civilian law enforcement agency that conducts investigations into incidents involving police

officers where there has been death, serious injury or allegations of sexual assault. The SIU

is independent of the police and is arm’s length to the Ministry of the Attorney General.

Between January 2000 and June 2006, the SIU conducted 784 investigations. While Black

people represented only 3.6% of the Ontario population, they represented 12% of all

civilians involved in SIU investigations, 16% of SIU investigations involving police use of

force, and 27% of all investigations into police shootings. Additional analysis indicates that

the police shooting rate for Black Ontario residents (4.9 per 100,000) was 7.5 times higher

than the overall provincial rate (0.65 per 100,000) and 10.1 times greater than the rate for

White civilians (0.48 per 100,000).

Finally, when examining cases where the death of a civilian was caused by police use of

force, the over-representation of Black people becomes even more pronounced: Black

people represent 27% of all deaths caused by police use of force and 34.5% of all deaths

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

11

caused by police shootings. The police shooting death rate for Black people (1.95 per

100,000) is 9.7 times greater than the provincial rate (0.20 per 100,000) and 16 times

greater than the rate for White people (0.12 per 100,000). The results for Indigenous people

were strikingly similar.

1

In another recent study, Carmichael and Kent (2014) examined variations in police killings

across 39 of Canada’s largest cities over a 15-year period. Information on police use of

force cases was derived from media accounts, not official statistics. The results of their

pooled time-series analysis are highly consistent with the ethnic threat hypothesis: police

killings are positively associated with the size of an urban centre’s racial minority population. In

other words, cities with high racial minority populations experience more cases of lethal police

activity than cities with small racial minority populations. This relationship persists even after

controlling for crime rate and various measures of socioeconomic disadvantage. Interestingly,

Carmichael and Kent (2014) also found that the greater the representation of female officers,

the lower the rate of police killing. The relationship between officer gender and use of force is

discussed further below. A limitation of this study is that it does not disaggregate the racial

minority category. In other words, the study cannot determine whether Canadian cities with

high Black populations have higher use of force rates than cities with high populations of other

racial minority groups.

The relationship between race and police use of force in Canada was further confirmed

by the release of a CBC report

in June 2018. A team of CBC researchers had scoured both

police reports and media accounts to compile a dataset of 461 individuals who had been

killed by police activity, in Canada, from 2000 to 2017. This is likely the first attempt at

establishing a national dataset of lethal use of force cases in Canada. The results strongly

indicate that both Indigenous and African Canadians are grossly over-represented in police

use of force incidents that result in death. For example, although Black people represented

less than 2.5% of Canada’s population during this period, they comprised almost 8% of all

police killings. Black over-representation was particularly large in certain urban centres. For

example, during this 17-year period, Black people in Toronto made up approximately 8.3%

of the city’s population. By contrast, they comprised nearly 37% of Toronto residents killed

1

Toronto data from this broader study of Ontario use of force cases will be explored in more detail

in Section C of this report.

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

12

by police use of force. It is also important to note that in 22% of all cases, the CBC could

not identify the race of the civilian. In other words, if any of these missing cases involved

individuals of African Canadian background, Black over-representation in deadly force

incidents would actually be higher than the numbers above already indicate.

In sum, Canadian research on police violence has been greatly hindered by the fact that

police services in this country do not routinely collect or release official statistics on police

shootings or other use of force incidents.

2

Moreover, research on racial differences in

policing outcomes is equally difficult to conduct because there has traditionally been an

informal “ban” on the dissemination of any type of information that breaks down criminal

justice statistics – including police shootings – by civilian racial background (see Wortley

1999). Nonetheless, the limited Canadian data that does exist strongly suggests that, as in

the United States, Black Canadians are over-represented in police use of force statistics.

This disparity is an issue that deserves more research and policy attention.

Racial disparity in context

While there is little debate in the U.S about the fact that Black people are over-represented

in police use of force statistics, there is considerable debate among criminologists, police

officials and politicians about the reasons for that over-representation. In summarizing the

American research on deadly force by police, Locke (1996: 135) observes that: “What every

single study of police use of fatal force has found is that persons of colour (principally Black

males) are a disproportionally high number of the persons shot by the police compared

to their representation in the general population. Where the studies diverge are the

reasons for that disproportionality.” On the one hand, some argue that racial disparities

are a product of bias. Others, however, maintain that racial disparities are a product of

legitimate police practices.

Some American scholars and social critics have argued that a combination of explicit,

implicit and systemic racism explains the fact that Black people are more likely to be the

victim of police violence than members of the White majority. In order to support this

2

There is some evidence that the willingness to collect and disseminate race-based data has

recently increased among some Canadian policing agencies. For example, over the past year, both

the Toronto Police Services Board and Ontario’s Special Investigation Unit have committed to

collecting data on the race of civilians involved in police use of force incidents. However, it appears

that this data will not be available for a couple of years.

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

13

argument, these authors frequently highlight specific cases in which the police have clearly

used excessive force when dealing with Black citizens (the Rodney King case, the Abner Louima

case, the Amadou Diallo case, the Tamir Rice case, the Freddie Grey case, the Michael Brown

case, the George Floyd case, etc.). They note that almost all of the “questionable” police

shooting deaths in the United States have involved African American males. Others focus on

the fact that Black males are particularly over-represented in official statistics that document

unarmed citizens who have been shot and killed by the police (see Ross 2015). For example,

Nix and his colleagues (2017) found that, in 2015, 38 of the 99 unarmed persons killed by a

police shooting were described as Black (38%), even though Black people represent only 13%

of the U.S. population. Overall, this study found that Black people were twice as likely as White

people to have been unarmed when shot and killed by the police. Support for the racism

hypothesis is further supported by survey results which suggest that the majority of Black

police officers in the United States feel that White officers are more likely to use physical force

against Black citizens than White citizens (Mann 1993; Sparger and Glacopassi 1992; Locke

1995; Tagagi 1978; Locke 1996; Walker et al. 2004).

Recently, scholars have argued that the over-representation of Black people in use of force

statistics may be strongly associated with racial bias at earlier stages of the policing process.

Racial profiling research, for instance, indicates that young Black males are much more likely

to be stopped and searched by the police than their White counterparts (Tanovich 2006;

Wortley 2018). In other words, Black youths have many more antagonistic street encounters or

confrontations with the police than White youths. This fact alone increases the probability that,

compared to White people, Black people may eventually become involved in a police

encounter that will escalate into a use of force incident (Menfield et al. 2018).

Despite these compelling results, most American policing scholars have nonetheless

argued that the positive correlation between Black racial background and police use of

force does not prove that there is a problem with police racism or racial bias. They argue

that disparity does not prove discrimination. The argument is that other factors, besides

race, must be taken into account before the presence of racial bias can be established.

Some of the most important variables – including civilian characteristics, officer characteristics

and situational factors – are described below.

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

14

Civilian characteristics

Gender: Males are significantly over-represented in American use of force statistics.

For example, over the past decade, males have constituted 90% to 95% of civilians killed

by police shootings in the United States, although they represent only 50% of the U.S.

population. Several studies suggest that, controlling for situational factors, the police are

more likely to use force – or greater levels of force – against male than female suspects

(Garner, Maxwell, & Heraux, 2002; McCluskey, Terrill, & Paoline, 2005; Terrill & Mastrofski,

2002; Terrill & Reisig, 2003; Terrill, Paoline, & Manning, 2003; Crawford & Burns, 1998;

Schuck, 2004; Terrill, 2005; Kaminski, Digiovanni and Downs 2004). By contrast, only a

handful of studies have found that suspect gender has no impact on the use of force

decisions (Engel, Sobol, & Worden, 2000; Lawton, 2007; Morabito & Doerner, 1997).

Age: In general, American research suggests that age is negatively associated with police

use of force. A number of studies suggest that, controlling for situational factors, officers

are more likely to administer force against younger than older civilians (McCluskey & Terrill,

2005; Paoline & Terrill, 2007; Terrill & Mastrofski, 2002; Terrill & Reisig, 2003). However,

some studies found that age is not a significant predictor of the level of force used by the

police (Crawford & Burns, 1998; Engel et al., 2000; Kaminski et al., 2004; Terrill et al., 2008).

Since American Census estimates suggest that the Black population is significantly younger

than the White population, racial differences in age might help explain racial disparities in

police use of force.

Socio-economic status: Despite the strong bivariate correlation between race and police

violence, some critical criminologists have argued that the over-representation of African

Americans in use of force incidents is more about social class than race (Walker et al. 2004).

They maintain that, regardless of race, police tactics of control and coercion are focused on

poor, socially disadvantaged segments of society. As Klockars (1996: 13) notes, when it comes

to police abuse, lower-class people are “the persons who are the least likely to complain and

the least likely to be believed if they do.” Thus, the over-representation of African Americans

in use of force cases could be partially explained by their over-representation in poor, socially

disadvantaged communities. This explanation is far from comforting. In theory, police

discrimination against poor people is just as upsetting – and unethical – as police

discrimination against racial minorities. A policing focus on poverty also represents a

form of systemic racism – since Black and other racialized groups are over-represented

within economically disadvantaged communities.

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

15

Despite the theoretical relevance of social class, research findings with respect to civilian

social class and use of force are somewhat inconclusive (Klahm & Tillyer, 2010). While

several studies suggest that there is a negative relationship between socio-economic class

and use of force (Friedrich, 1980; McCluskey & Terrill, 2005; Terrill & Mastrofski, 2002; Terrill

& Reisig, 2003), other studies indicate only a weak, statistically insignificant relationship (Sun &

Payne, 2004; Paoline & Terrill, 2005). It is important, however, to interpret any findings related

to civilian socio-economic class with caution. Social class, at the individual level of analysis,

is difficult to measure. Some studies have been criticized for using unreliable observer

perceptions of civilian social class rather than self-reports (see Weitzer & Tuch, 2004;

Klahm & Tillyer 2010).

Criminal record: A number of scholars have argued that police use of force studies should

try to control for civilian criminal history. Indeed, previous research suggests that a high

proportion of civilians involved in use of force cases have a previous criminal record

(see reviews in Menifield et al. 2018, Zimring 2017). Previous criminality may increase

the likelihood that a civilian will draw legitimate police attention, resist arrest and act in

a violent or aggressive manner towards law enforcement officials. Police officers may

also become “vigilant” when dealing with known violent offenders. Hypervigilance, in

turn, could increase the likelihood that force will be used. Importantly, in the absence of

more precise situational information, criminal record has often been used as a “proxy”

measure for civilian behavior during police encounters. Civilian criminal record, in other

words, is often used to legitimize use of force decisions (i.e., the person had a criminal

record and therefore must deserve the force they received). Critics, however, maintain

that a criminal record does not justify police use of force. For example, a person cannot

be shot by the police just because they have a criminal record. These scholars argue

that it is much more important to measure situational factors – including a civilian’s

actual behavior during police encounters – than criminal history.

Situational factors

Civilian impairment: Some scholars have suggested that civilian impairment could increase

the likelihood of police use of force. The logic is that persons, intoxicated on drugs or alcohol,

may act in a more irrational, aggressive or violent manner towards the police and eventually

compel police action. However, the empirical evidence is mixed. While some studies suggest

that civilian impairment increases the likelihood of police use of force (Engel et al., 2000;

Friedrich, 1980; McCluskey & Terrill, 2005; McCluskey et al., 2005; Paoline & Terrill, 2007; Terrill

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

16

& Mastrofski, 2002; Terrill et al., 2003; Terrill et al., 2008), other studies reveal no significant

relationship between intoxication and use of force decisions (Lawton, 2007; Morabito &

Doerner, 1997; Crawford & Burns, 1998). Doubt has also been raised about the validity of

“civilian intoxication” measures. Civilian intoxication measures are often based on officer

perceptions rather than self-reports and physiological testing. There are also concerns

that officers often conflate civilian intoxication with symptoms of mental illness.

Civilian mental illness: Civilian mental illness can be viewed as both an individual

characteristic and a situational variable. A growing body of American evidence suggests

that a large proportion of all police use of force cases involves civilians with mental

illness and/or experiencing a mental health crisis at the time of their interaction with

police (Morabito and Socia, 2015; Parent 2011). This includes cases of severe depression

in which civilians try to induce “suicide by cop.” It is hypothesized that, as with cases

of civilian intoxication, people in mental crisis may appear “irrational” during police

encounters, fail to obey police instructions, or act in a violent or threatening manner

towards police officers. All of these factors may increase fear and concerns about

officer safety and ultimately increase the likelihood of a use of force event.

Although a topic of growing public concern, empirical research on the relationship between

mental health and police use of force is quite limited. Most research on this topic has only

examined police perceptions of mental illness rather than official diagnoses or civilian self-

reports (Desmarais et al., 2014; Livingston et al., 2014; Watson, Corrigan & Ottati, 2004;

Wells & Schafer, 2006; Engel, 2015; Hails & Borum, 2003; Morabito, 2007; Morabito & Socia,

2015; Parent, 2007). It is estimated that approximately 10% of all police-civilian encounters

involve people with a mental illness (Hails & Borum, 2003; Morabito, 2007).

A number of studies have also produced findings that suggest a positive relationship between

mental illness and the likelihood of experiencing police use of force incidents. For example,

Bailey, Smock, Melendez and El-Mallakh (2016) found that the police are more likely to deploy

CEWs (Tasers) on mentally ill persons than on others. Similarly, Hall et al., (2013) found that

one in six use of force incidents involves a person exhibiting common signs of Excited Delirium

(often associated with a mental illness). Further, Parent (2011) examined all police killings in

British Columbia over a 10-year period and found that one-third of all cases involved a person

in mental health crisis.

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

17

However, other studies suggest that mental illness has no impact on use of force decisions

(see Morabito & Socia, 2015). Moreover, in jurisdictions that have employed Crisis Intervention

Teams (CITs), use of force against persons with mental illness declines (Morabito et al., 2012).

CIT is a specialized police approach where officers are trained to effectively respond

and manage calls involving mentally ill persons and act as liaisons to the mental health

system (Morabito et al., 2012; see also Borum, Deane, Steadman, & Morrissey, 1998).

A major limitation of research on the policing of mentally ill populations involves the

identification of those with mental health problems. Data validity often depends on the ability

of individual police officers to identify the signs of mental illness and react accordingly.

As discussed above, officers often find it difficult to differentiate between people who are

impaired or intoxicated and people with mental health issues (Alpert, 2015; Morabito & Socia,

2015). As Morabito et al., (2012, p. 61) note: “police officers may encounter individuals who

have a mental illness and are also under the influence of drugs or alcohol – increasing their

difficulty in managing the incident and perhaps making it difficult for the officer to recognize

the mental illness.” Such measurement challenges may contribute to inconsistent research

findings and impede efforts to determine the true relationship between mental health and

police use of force.

Civilian behaviour during encounters with the police: Technically, the police are only

permitted to use physical force – including firearms – when they or others are either

threatened or attacked by a suspect. In other words, officers must fear for their own safety,

the safety of fellow officers, or the safety of other civilians before they make the decision

to use force. This fear must be considered reasonable. In support of this general principle,

previous research consistently reveals that, in a high proportion of police shooting cases,

civilians were alleged to have been threatening, attacking or shooting at police officers

(Balko 2014; Haider-Markel et al. 2017; Klinger et al. 2017; Zimring 2017). Research also

suggests that a high proportion of use of force derives from police attempts to arrest

suspects accused of criminal behavior. In many cases it is alleged that force is justified

because civilians have actively tried to resist arrest or avoid apprehension (Klahm & Tillyer,

2010). Most research suggests that officers enforcing an arrest are much more likely to use

force than officers involved in other types of civilian interaction (McCluskey & Terrill, 2005;

Paoline & Terrill, 2007; Terrill & Mastrofski, 2002; Terrill et al., 2003).

It is important to note, however, that research on the temporal ordering of the arrest/use of

force relationship is limited. Most studies, for example, are unable to determine whether force

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

18

was used before or after arrest initiation (Klahm & Tillyer, 2010). Furthermore, the

operationalization of “arrest” and “use of force” has been inconsistent across studies. Some

studies, in fact, classify arrests as a type of use of force – regardless of whether physical force

was used or not (see Alpert & Dunham, 2004). By contrast, other empirical studies measure

police use of force in terms of physical strikes and blows or the use of weapons against

civilians (see Bazley, Lersch, & Mieczkowski, 2007).

Civilian demeanour: Police scholars have also argued that the demeanour of civilians may

have a major impact on police decision making – including the decision to use force. Some

studies have observed that the police are more likely to use excessive force against citizens

who are argumentative, belligerent or defy their authority (Garner and Maxwell 2003;

Macdonald et al. 2003; Terrill 2003). It has been suggested that some police officers react

negatively to even legitimate questions from civilians. In other words, civilians who “flunk

the attitude test” or display “contempt of cop” may be more vulnerable to police violence

than those who are passive or compliant (see Worden 1995).

Other research has suggested that young Black males are more likely to be rude and

disrespectful towards the police than young White males (see Walker 2000). This has led

some to hypothesize that the poor or disrespectful demeanour some Black youth display

towards the police may partially explain their over-representation in police use of force

statistics. However, as with the social class hypothesis, the demeanour explanation

does not validate the over-representation of racial minorities in cases of police violence.

Poor civilian demeanour towards the police is not a legal justification for police use of

physical force.

Overall, the research record is mixed. Some studies indicate that police are more likely to

use force against suspects with poor demeanour towards the police (Brooks, 1993; Engel

et al., 2000; Garner et al., 2002), while other research suggests that civilian demeanour has

no impact (Paoline and Terrill, 2007; Terrill and Mastrofski, 2002; Terrill and Reisig, 2003).

Unfortunately, some scholars have questioned the measurement of civilian demeanour

and note that it has been operationalized inconsistently across studies (Klahm & Tillyer,

2010). Inconsistencies in the measurement of demeanour may, in fact, help explain

inconsistent results.

Previous research has also not explored the relationship between racial profiling and

civilian demeanour. This is an important oversight. For example, previous research (see

Wortley and Owusu-Bempah 2009; Wortley and Owusu-Bempah 2011) reveals that Black

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

19

people are much more likely to be stopped and searched by the police than White people.

Research also suggests that those who are frequently stopped and searched by the police

are more likely to develop negative attitudes towards the police and are more likely to believe

that the police are racially biased. These negative attitudes may translate into a more hostile,

non-compliant or questioning demeanour towards the police during subsequent police

encounters. Negative demeanour, in turn, could increase the likelihood of police use of force.

This is an issue that should be the subject of future research.

It should be further noted that some critics have suggested that researchers have focused

far too much on citizen demeanour towards the police and not enough on police demeanour

towards civilians (see Walker 1992; Walker 2000). Indeed, civilians may sometimes display

disrespectful or defiant attitudes towards the police as a response to police mistreatment,

verbal abuse or incivility. Is it the demeanour of citizens that leads to violent police encounters,

or does the demeanour of the police officer set the tone for many civilian-police interactions?

Presence of bystanders: Previous research has also examined whether the presence

of other police officers and/or civilian bystanders influences police use of force decisions.

Several studies have found that police officers are more likely to use force when additional

officers are present (Garner et al., 2002; Paoline & Terrill, 2007; and Terrill & Mastrofski,

2002). Other research has found no relationship between use of force and the number of

officers present (Engel et al., 2000; McCluskey, et al., 2005). To date, most studies suggest

that the presence of civilian bystanders has no impact on police use of force decisions

(McCluskey et al., 2005; Paoline & Terrill, 2005; Schuck, 2004; Terrill & Mastrofski, 2002;

Terrill et al., 2008). However, there has been some speculation that, in the future, the

presence of civilians with cell phones might curb police brutality within some crowded

social settings.

Community characteristics: Research suggests that neighborhood characteristics may

have a major impact on police use of force. Several studies have found that use of force

rates are significantly higher in economically disadvantaged, high-crime communities than

wealthy, low-crime communities. Importantly, American research reveals that neighbourhood

crime – especially violent crime – typically emerges as a stronger predictor of police use of

force than neighborhood poverty. In many American cities, high-crime communities also

have large Black populations. Thus, some scholars have argued that Black people are over-

represented in police use of force statistics because they are more likely to live in poor, high-

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

20

crime communities. Some American research, in fact, suggests that racial disparities in police

shootings are rendered statistically insignificant after controlling for community-level crime

rates (see review in Johnson et al. 2019).

However, critics warn that community-level crime rates should not be used to justify the

use of force against specific individuals. An individual’s presence in a high-crime community

does not justify police use of force. Indeed, many of the most celebrated cases of police

brutality have taken place in high crime neighborhoods. Nonetheless, many studies appear

to use community crime rates as a proxy measure for minority aggression against police

officers. The suggestion seems to be that – if the police use force in high crime neighbourhoods

– it is most likely “legitimate.” Others suggest that use of force may be more prevalent in high-

crime communities because of police deployment patterns (high-crime communities have a

greater police presence than low-crime communities) and more aggressive police strategies

(Menifield et al. 2018). Another possibility is that police officers are more vigilant (on edge) in

high-crime communities and more anxious about their personal safety. This fear or

apprehension could directly or indirectly impact use of force decisions.

Police officer characteristics

Officer gender: Some police scholars hypothesize that female police officers, due to

gender socialization norms and higher levels of empathy, are less aggressive and thus less

likely to use force than their male counterparts. However, research on the impact of officer

gender has been mixed. Most studies suggest that officer gender is not a significant predictor

of use of force (Klahm & Tillyer, 2010; Kaminski et al., 2004; Lawton, 2007; McCluskey & Terrill,

2005; Paoline & Terrill, 2007; Terrill & Mastrofski, 2002; Terrill, Leinfelt, & Kwak, 2008). Other

research, however, has found that, after controlling for situational factors, male officers are

more likely to use force – especially deadly force – than female officers (see reviews in Garner

et al., 2002; Alpert & Dunham, 1997; Charmichael & Kent, 2015).

Officer age and experience: Officer age and experience are highly correlated. Veteran

officers tend to be older than officers with little work experience. Some studies suggest that

officers with more experience are less likely to use force than younger, less experienced

officers (Worden 2015; McElvian and Kposawa 2008; Paoline & Terrill, 2007; Terrill & Mastrofski,

2002). However, other studies indicate that – after controlling for rank and type of policing

assignment – officer experience has no influence on use of force decisions (Lawton, 2007;

McCluskey & Terrill, 2005; Sun & Payne, 2004). Finally, other studies suggest that while officers

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

21

with more years of experience are less likely to use deadly force than younger officers, they

are actually more likely to employ other, non-lethal, use of force techniques (Crawford & Burns,

1998; see also Kaminski et al., 2004; Morabito & Doerner, 1997; Klahm & Tillyer 2010).

One factor that might influence the relationship between officer experience and use of

force is the type of policing assignment. Younger officers are more likely than older officers

to be assigned to frontline patrol work that involves aggressive or proactive policing tactics

– including stop, question and frisk practices (see Worden 2015). This type of work increases

the frequency of negative interaction with civilians and thus the probability of use of force.

By contrast, older, more experienced officers are more likely to be assigned to special units,

detective work or supervisory positions that will decrease their likelihood of experiencing a

use of force incident.

Officer racial background: A number of scholars have hypothesized that White police

officers, due to both explicit and implicit biases, should be more likely to use force against

Black civilians than Black police officers. However, a number of studies have found that

officer race is not a significant predictor of police shootings of Black civilians. In fact, a

few American studies have found the opposite – that Black civilians are more likely be shot

by Black than White officers (see Menifield et al. 2019; Johnson et al. 2019). A number of

factors might explain this unexpected relationship – including the fact that Black officers

are more likely to work in large urban centres and are more likely to be assigned to patrol

high-crime areas within those cities. Nonetheless, this finding has contributed to the argument

that increasing diversity will not necessarily decrease police use of force incidents. Importantly,

while research has focused on shootings in general – it has not yet adequately explored

whether White officers are more likely to be involved in the shooting deaths of unarmed Black

civilians or other “illegitimate” use of force cases.

Officer education: The education of an officer and whether this has any impact on the use

of force has received considerable attention through general discussion, but relatively little

empirical research has focused on this issue. It is argued that those who have attained a

higher level of education possess better decision-making skills and should be less likely to

resort to violence (Worden, 1990; see also Paoline & Terrill, 2007). The empirical evidence

around this issue has produced mixed findings. Sun and Payne (2004) reported that an

officer’s level of education did not influence the likelihood of force being used. Conversely,

Paoline and Terrill (2007) found that officers with a post-secondary degree were less likely

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

22

to use force compared to their colleagues with only a high school education (see also

McElvain & Kposowa, 2008). Similarly, Rydberg and Terrill (2010, p. 110) found that “officers

with some college exposure or a four-year university degree are significantly less likely to

use force relative to non-college-educated officers.”

The results of multivariate analyses

A growing number of studies have examined the impact of race on police use of force after

statistically controlling for other theoretically relevant factors. As with much of the research

on this controversial topic, the findings have varied. Some multivariate analyses have found

that race is a significant predictor of police use of force (see reviews in Shane 2018; Buehler,

2017; Nix et al. 2017; Goff et al. 2016; Ross 2015; Crow & Adrion, 2011; Gau, Mosher, & Pratt,

2009; Lin & Jones, 2010; Brown & Langan, 2001; Eith & Durose, 2011; Jacobs & O’Brien, 1998;

Smith, 2004; Terrill & Mastrofski, 2002), while others have found that the impact of race is

rendered statistically insignificant after controlling for other situational and community-level

variables (Tregle et al. 2019; Worrall et al. 2018; Engel et al., 2000; Garner et al., 2002; Lawton,

2007; McCluskey et al., 2005; Morabito & Doerner, 1997; Sun & Payne, 2004). The following

examples are illustrative of the range of research methodologies and findings that have

emerged within the American use of force literature over the last five years.

Ross (2015) examined the impact of race on police shootings using data from the U.S.

Public Shooting database. He used a geographically resolved, multilevel Bayesian analysis

to estimate county-level risk levels of being shot by the police. Ross (2015) found that, after

controlling for a wide variety of other factors, the median probability of being unarmed and

shot by the police was 3.5 times greater for Black civilians than White civilians. Furthermore,

this study found that the average risk of being shot by the police was the same for unarmed

Black suspects as it was for armed White suspects.

Other results indicate that police shootings were most likely to take place in larger urban

communities with high Black populations and high levels of poverty and socioeconomic

inequality. However, this study found no evidence to suggest that the observed racial

disparities in police shootings could be explained by county-level crime rates. Ross (2015)

concludes that these results support the argument that racial bias contributes to police-

related killings of unarmed Black men in the United States.

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

23

In a similar study, Scott et al. (2017) examined deadly force cases, from 213 metropolitan

areas, over a 17-year period (1998-2015). The authors found evidence that American police

officers are more likely to shoot and kill Black suspects even after statistically controlling

for civilian behaviour, community characteristics and race-based measures of criminality.

Goff et al. (2016) examined use of force records for 12 large police services across the United

States. Their examination found that, even after statistically controlling for racial differences in

arrest patterns, participating departments still demonstrated racial disparities across multiple

levels of force severity. Second, even when controlling for the uncommon occurrence of

arrests for serious violent crime, “25%-55% of participating departments still revealed robust

racial disparities that disadvantaged Blacks” (Goff et al. 2016).

In another recent study, Menefield, Shin and Strother (2019) examined a dataset that captured

documented cases of police lethal use of force in the United States from 2014 to 2015. The

authors found that Black racial background still emerged as a significant predictor of lethal

force after controlling for various individual and situational factors, including whether the

civilian was armed at the time of the incident, had a criminal record, or if the police encounter

resulted from the commission of a violent crime. However, contrary to the racial bias

hypothesis, White police officers were no more likely to kill racial minority suspects than racial

minority police officers. Further analysis of the data revealed that lethal force is significantly

related to community racial composition (i.e., percentage Black), but not local rates of violent

crime. The authors conclude that the disproportionate killing of African Americans by police

officers does not appear to be driven by micro-level racism. It is more likely to be explained by

macro-level policing policies and practices that target predominantly Black communities.

In another recent study, Johnson, Tress, Burkel, Taylor and Cesario (2019) examined 2015

lethal police shootings in the United States. This study also found that officer race is

unrelated to the shooting of Black suspects. In other words, they found no evidence that

White officers were more likely to shoot and kill Black civilians than racial minority officers.

Furthermore, these authors argue that observed racial disparities in police use of force

statistics can be explained by race-specific, county-level crime rates. In other words, the

authors suggest that Black civilians are more involved in police shootings because, at the

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

24

aggregate level, Black people have a higher rate of criminal involvement than White people

(see also Tregle, Nix and Alpert 2019).

3

It is important to highlight the potential limitations

of this interpretation. The authors are using aggregate racial data (race-specific crime rates)

to explain racial differences that emerge during micro-level police-civilian encounters. This

is often referred to as the “ecological fallacy.” It implies that the individuals involved in

police shooting deaths must have been involved in criminal activity because – at the group

level – Black people have higher crime rates. An alternative explanation might suggest that,

because Black people as a group have a higher crime rate, officers are more wary, anxious

or vigilant in their presence and this may contribute to biased use of force decisions (for an

additional critique of this article see Knox and Mummolo 2020).4

A note on simulation studies

A growing body of research has examined the relationship between race and police use

of force under controlled, experimental conditions (see James, James & Vila, 2016; James,

Klinger & Vila, 2014; James, Vila & Daratha, 2013). These studies use highly realistic

simulation technology to explore the conditions under which officers decide to discharge

their firearm. The results of these studies suggest that, contrary to the discrimination

hypothesis, officers are slower to shoot armed Black suspects than armed White suspects.

The data also suggest that officers are less likely to shoot unarmed Black suspects than

unarmed White suspects. Importantly, simulation studies have also demonstrated that implicit

racial bias – as measured by the Harvard Implicit Association Test (IAT) – does not appear to

increase the likelihood of shooting unarmed Black suspects (see James et al. 2016).

3

Using data from a national American sample of lethal police shootings, Tregle et al. (2019) found

that racial disparities in deadly police encounters varied dramatically by the type of benchmark

employed. Black civilians were significantly over-represented in lethal police shootings using Census

benchmarks and benchmarks predicting the likelihood of involuntary police contact. However,

according to the authors, Black civilians appear to be less likely to be shot when benchmarked

on aggregate violent crime arrests or weapons arrests.

4

In another recent study, Worrall et al. examined a sample of 300 cases in which officers had drawn

their firearms on a civilian. About half these cases involved a Black person. Controlling for other

situational factors, the authors found that officers were less likely to shoot Black civilians than White

civilians after they had drawn their firearm. However, this study did not control for racial differences

in the likelihood of police contact or the possibility that, due to bias, officers have a lower threshold

when it comes drawing firearms on Black civilians. In other words, it is possible that the results were

skewed by the possibility that officers more frequently draw their firearms – without strong

justification -- when dealing with Black rather than White civilians.

Use of force by the Toronto Police Service

_______________________________________________________

Ontario Human Rights Commission

25

Critics, however, are quick to identify the potential limitations of simulation research. For

example, Fridell (2016) argues that, no matter how realistic, artificial laboratory settings

cannot truly replicate “real world” conditions because officers know that there are no real

consequences (i.e., death, serious injury). This might cause officers to be “under-vigilant”

when dealing with scenarios involving minority suspects. Furthermore, although the purpose

of simulation studies are never fully disclosed to participants, officers can easily detect that

they are being tested for their use of force decision-making under different conditions. Thus,

during simulation studies, officers may be particularly careful when confronted with Black

suspects because they do not want to be identified as racially biased. The same caution might

not apply on the street (Terrill 2016).

A note on police subcultures

A number of scholars have examined the impact that the police subculture may have on

the nature and extent of police violence (see reviews in Kappeler et al. 1997; Kelling and

Kliesmet 1996). The literature reveals that the police subculture may increase the likelihood

of police violence for the following five reasons:

1) The militaristic “war on crime” orientation that permeates most modern police

services creates an “us against them” mentality among police officers. To the