Bank of England Page 1

Expectations, lags, and the

transmission of monetary

policy - speech by

Catherine L. Mann

Given at the Resolution Foundation

23 February 2023

Bank of England Page 2

Speech

1. Introduction

Economists often reference the ‘long and variable’ lags of monetary policy, first introduced

by Milton Friedman in 1961. In the central banking world, 18 to 24 months is often quoted

as how long it takes for changes in monetary policy to feed through to inflation, even as

certainly this effect accumulates over that timeframe. Although this has by now become a

sort of folk wisdom, the economic and policy environment over the past few years has

prompted me to re-examine these long and variable lags.

As I’ve noted in numerous previous speeches

1

, the speed and magnitude of monetary

transmission depends on the underlying structure of the economy, shocks the economy

faces, and on the behaviour of financial markets, firms and households. Monetary

transmission will change when the economy and the economic environment changes.

Empirical estimates of the effect of monetary policy on macroeconomic aggregates are

strictly speaking only valid in-sample – unless we believe that the structure of the economy

has not changed in a way that would invalidate our estimates.

We have been raising Bank Rate for more than a year now and by 390 basis points in

total. Should we have seen more of an effect on the real economy and inflation already?

Perhaps the ‘long and variable’ lags are influenced by how monetary policy is transmitted

through financial markets or via the expectations of participants in the real economy.

Certainly the sequence of shocks that we have encountered must also matter.

In the following examination of the a) data and research, b) presentation of a new financial

conditions index, and c) modelling of sequential shocks and expectations in a theoretical

model, I will argue that 1) financial markets have absorbed a substantial degree of the

tightening to date; 2) that the sequence of shocks and embedding of inflation risks a

troubling change in expectations formation via an increase in the share of

backward-looking participants in the real economy; which 3) risks a worse inflation and

output outcome in the longer term. This leads me to my conclusion that further tightening

and sooner rather than later likely is needed to ensure the effectiveness of monetary policy

to achieve the objective of 2% sustainably in the medium term.

1

See Mann, 2022a and 2022b.

Bank of England Page 3

2. What is the transmission mechanism?

To structure the content of this speech, let me start with ‘the monetary transmission

mechanism’. The Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee uses a single interest rate –

Bank Rate – that affects only a narrow set of financial institutions.

2

How does that narrow

conduit affect the behaviour of households and firms, and ultimately output and prices in

the economy? Central banks rely on financial markets to pass through their policy choices

in a way that is consistent with their intended consequences, alongside the role for

expectations. Households and firms then react to these changed financial conditions and

in light of their own expectations, which subsequently affects output and prices.

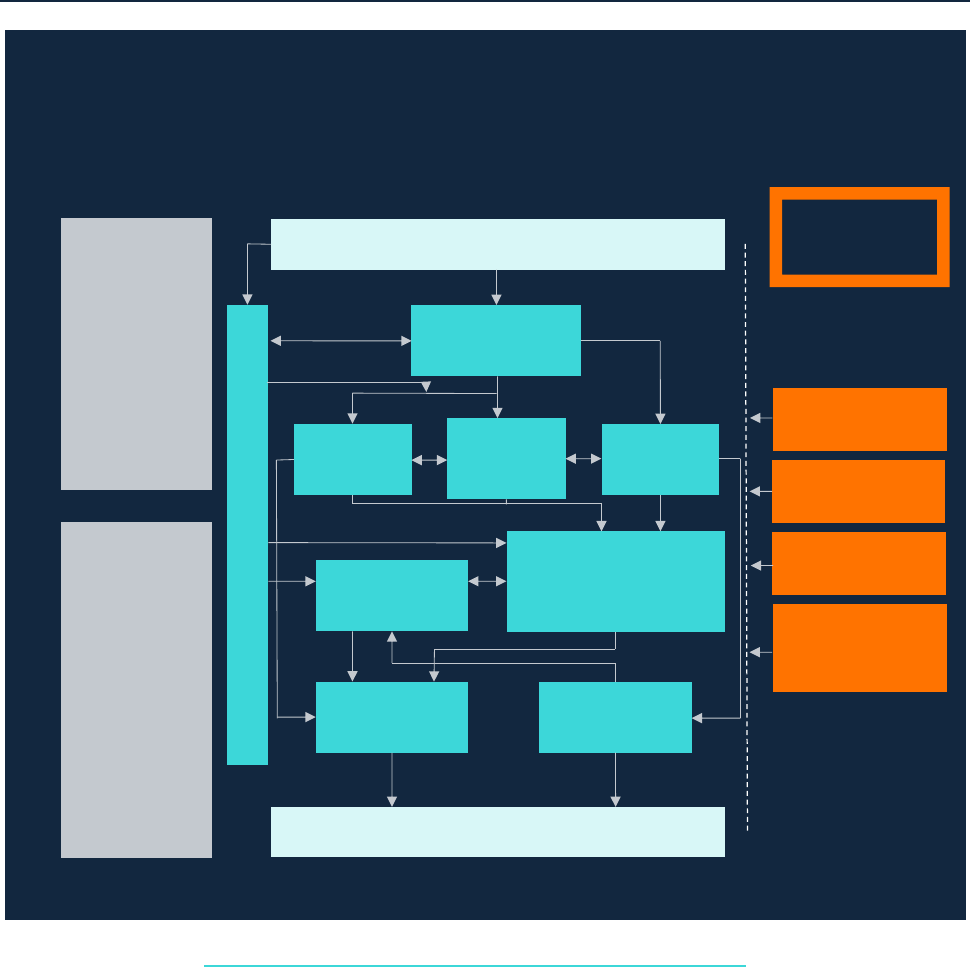

Chart 1 shows a stylised representation of the main channels through which monetary

policymakers expect changes in policy rates to transmit through the economy. The

effectiveness of monetary policy is influenced by the functioning of these individual

channels, and the interactions between them, denoted by the arrows.

2

Of course, we also have conducted Quantitative Easing and engaged in forward guidance in order to

influence risk-free rates further along the yield curve but these are less direct policy tools. Our main

monetary policy instrument at the moment is certainly Bank Rate.

Bank of England Page 4

Chart 1: Stylised representation of the main channels of the

monetary policy transmission mechanism

Source: Adapted from ECB (n.d.) ‘Transmission mechanism of monetary policy’.

Factors outside of the central bank’s control and interactions among the channels can

amplify or dampen the pass-through of any given policy choice. I’d like to highlight several

stages through which the transmission mechanism works in each of the following sections

of this speech.

The first stage comprises the transmission from a change in the policy rate through

financial markets. The overall transmission mechanism is often summarised in a ‘financial

conditions index’. But, as with many other cases of aggregation, it is important to look

under the bonnet for where changes in the policy rate feed through to specific financial

market variables, such as the exchange rate, the interest rates that firms and households

face, as well as other asset prices. Changes in the policy rate don’t transmit

Bank rate

Shocks outside

the control of the

central bank

Changes in risk

preferences

Changes in the

global economy

Changes in fiscal

policy

Changes in

commodity

prices

Expectations

Money market

interest rates

Money &

credit

Asset prices

and risk

premia

Exchange

rate

Wage and

price-setting

Supply and

demand in goods

and labour markets

Domestic

prices

Import

prices

Price developments

Stage 1:

transmission

through

financial

markets

Stage 2:

transmission

to the real

economy

Bank of England Page 5

instantaneously though, but rather at different speeds to different financial market

variables, which is one source of lags in monetary policy.

The second stage of the transmission mechanism describes the pass-through of changes

in financial conditions to the real economy, through the price-setting decisions of firms,

wage negotiation behaviour of firms and households, as well as their spending, saving,

and investment decisions. This is the stage in the transmission mechanism where lags

arguably are most obvious because of agents’ partial attentiveness and the staggered

nature of contracts, among other factors. Prices and wages are influenced by, and may

spill back into demand and supply, and labour markets.

But to start the transmission process, a tightening in financial conditions should mean

households cut back on consumption as the cost of borrowing rises, and the opportunity

cost of spending increases as saving rates rise. Firms may reduce investment, both in

response to rising borrowing costs, and in anticipation of worsening demand conditions.

Conditional on their pricing power and debt conditions, they may reduce prices or hold off

on increasing them in order to preserve their market share, or they may even increase

them to try to preserve cash flow.

Expectations – that is expectations of everything: policy, prices, demand, supply –

influence both financial and real-side channels but with different lags and with different

degrees of forward- versus backward-looking assessments of the current data and the

future. An often underappreciated feature of macroeconomics is that expectations about

the future can influence the present.

3

Expectations can affect wages and prices directly,

possibly before demand and supply conditions in goods and labour markets have changed

(Mann, 2022b).

However, there are also shocks, illustrated on the right-hand side of this diagram, that are

outside of the control of a central bank and can influence the key channels of the

transmission mechanism. These include for instance changes in fiscal policy, trade

linkages in the global economy, commodity prices, and risk preferences. In recent years,

economies and central banks across the world have faced a series of these shocks, which

most probably have influenced the long and variable lags – that is the effectiveness – of

how changes in Bank Rate affect the real economy and inflation.

3

In this current framework, in which central banks try to explain, as best as they can, the aim of and

reasoning for their policy choices, the stance of monetary policy is as much about Bank Rate today as it is

about Bank Rate tomorrow. Or even, as Woodford (2005) put it: “Not only do expectations about policy

matter, but, at least under current conditions, very little else matters.”

Bank of England Page 6

3. The transmission of monetary policy through financial markets

In the next few minutes, I would like to focus entirely on the first stage of the transmission

mechanism, the transmission of monetary policy through financial markets.

Chart 2 shows the level of Bank Rate compared to a so-called “shadow rate”

(Wu & Xia, 2016). This shadow rate can be thought of as showing the unobserved level of

the short rate that could prevail, taking into account the effects of the policy rate as well as

of unconventional monetary policy tools. Since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), central

banks have employed a range of conventional und unconventional monetary policy tools.

So far, I have only focused on the transmission mechanism of Bank Rate, which has been

the MPC’s active policy tool. The use of forward guidance and quantitative easing (QE) are

unconventional tools that were essential to the easing of the monetary stance while the

policy rate was restricted by its effective lower bound, but these may work through different

channels.

4

Chart 2: Wu-Xia shadow rate and Bank Rate

Source: Wu and Xia (2020) and Bank of England. Notes: The orange dotted line constrains the shadow rate

to the level of Bank Rate as suggested by the authors. Latest observation: February 2023.

4

For more information on QE and its transmission channels, see Busetto et al. (2022).

-10

-8

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

94 98 02 06 10 14 18 22

Percent

Bank Rate

Wu-Xia shadow rate

Bank of England Page 7

As a first step to assess the effectiveness of the monetary transmission mechanism, a

policymaker needs to understand how accommodative or tight the monetary stance is.

This is not as straightforward to determine in light of the unconventional tools and the

time-varying nature of r*. For a variety of reasons, the policy rate alone does not always

provide an accurate read on the monetary policy stance.

5

Over the last year and a half, monetary conditions have tightened significantly over a short

period of time, in response to the MPC’s Bank Rate increases. But, are the conditions

tight? Not just the speed and size of tightening matter here, but the starting point does

too. The MPC started tightening from what was a record-accommodative policy stance due

to the Bank’s response to the Covid-19 pandemic.

There is an obvious question on the interpretation of this shadow rate: Should monetary

policy stance be judged by the level or the change? Which one (or both) matter for overall

financial conditions and the real economy? To make an assessment on the level, you

would need a relevant reference point. Is an historical average a good reference point,

given the ‘structural break’ present in the data around the GFC? Compared to historical

average, the monetary stance is still loose. Compared to a post-GFC period, monetary

stance is tighter. But research also finds that the extent to which monetary policy affects

inflation depends on thresholds: that is, tightening from a loose stance has less of an effect

on inflation than tightening from a tight stance (Calza and Sousa, 2005).

Turning to a key part of the transmission mechanism – household debt-servicing costs.

Chart 3 shows the levels of mortgage rates at 2-year and 5-year horizons, alongside

maturity-matched OIS reference rates. The difference between mortgage rates (in the

dotted lines) and the maturity-matched OIS rate (in solid lines) is referred to as the

mortgage spread. Up until the GFC, mortgage and reference rates co-moved closely – a

relationship that broke down in the financial crisis. Spreads widened as reference rates fell

in response to falling policy rates and QE. But mortgage rates fell only very slowly over the

next decade, and never recovered the level of pre-crisis spreads. This is evidence, at least

over the sample period we are looking at, of lagged pass-through from changes in policy

rates to the rates households face on their mortgages.

5

Typically, shadow rates in the literature are constrained to be near or equal to the level of the policy rate

when it is above its effective lower bound (ELB). This made sense when the goal was to measure the easing

effect of unconventional monetary policy. Arguably, however, also in times when the policy rate is far above

the ELB, it is not a clean measure of the monetary policy stance. See for example Choi et al. (2022) who

construct a less restrictive measure of the monetary policy stance for the US.

Bank of England Page 8

Chart 3: Mortgage rates and OIS rates

Solid lines show OIS rates, and dotted lines the maturity-matched 75% LTV

mortgage rates

Source: Bank of England, Bloomberg Finance L.P, Moneyfacts and Bank calculations. Notes: For OIS data

pre-2008, a Gilt-OIS spread is applied to the equivalent-maturity gilt yield data. Data is monthly until July

2018, and daily thereafter. Latest observation: 7

th

February 2023.

Zooming in on the time since we started increasing Bank Rate, we see that mortgage rates

tracked reference rates quite closely, initially, on the way up. They have also somewhat

retraced their recent spike around the mini-budget turmoil of September 2022 – but not as

much as have reference rates. Interest rates spiked sooner than mortgage rates did,

reflecting again the lag in the pass-through from changes in reference rates to mortgage

rates.

It appears that pass-through from changes in risk-free rates to mortgage rates is highly

state-dependent, suggesting more rapid transmission as interest rates rise and slower

transmission as interest rates fall. Whereas the level of mortgages rates is higher than the

trough, they are about back to pre-GFC levels, and importantly, have loosened from last

autumn. Is this a tight stance for 2-year and 5-year mortgage rates? Notably, mortgage

rates are definitely looser than they were last autumn, even as Bank Rate has risen further

since.

Bank of England Page 9

Turning now to the equity market, Chart 4 shows a decomposition of moves in equity

prices into underlying components through the lens of a Dividend Discount Model. The

MPC’s tightening in monetary policy has had a considerable downward effect on equity

prices over the last twelve months. This is the direction monetary policy makers would

expect the transmission mechanism to work in a hiking cycle: higher interest rates weigh

on equity prices as future earnings and cash flows are discounted using a higher discount

factor. It would also make sense that higher interest rates would signal a worsening

economic outlook to financial markets, which should dampen expected shareholder

payouts, and potentially increase risk premia.

Chart 4: Decomposition of equity price moves of the FTSE All-Share

6

Cumulative percentage changes

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P, Tradeweb, Refinitiv Eikon and I/B/E/S from LSEG, IMF WEO and Bank

calculations. Latest observation: 1

st

February 2023.

But Chart 4 shows that, in fact, shareholder payout and most notably the equity risk

premium have made a positive contribution to equity prices since the beginning of last

year. These have outweighed the effects of monetary policy tightening through interest

rates. Shareholder payout, in aqua, captures a combination of realised cash flows to

investors, and their expectations for future payout, and is often used as a proxy for

market-implied views on the economic outlook. So, equity markets seem to have a reason

to believe the outlook has improved since the beginning of 2022, or at least some

6

The decomposition uses the Bank’s Dividend Discount Model. For more information, see Dison and Rattan

(2017).

-80

-60

-40

-20

0

20

40

60

80

Jan 22 Apr 22 Jul 22 Oct 22 Jan 23

Percent

Interest rates

Shareholder payout

Other

Equity risk premium

Cumulative change

in FTSE All-Share

Bank of England Page 10

remaining elevated tail risks from the Covid period seem to have receded. This could be a

result of their forward-looking nature, that inflation is expected to fall steadily this year, or

reflective of the fact that long term interest rates are expected to be lower than short term

ones.

Either way, this chart tells an interesting story about the net effectiveness of the monetary

tightening so far. The positive contribution of a falling equity risk premium implies that an

improving outlook is not enough to explain equity performance. Indeed, it implies that

equities have performed significantly better given what we know about interest rates and

growth expectations. It seems that the MPC’s tightening efforts have been in part offset by

this risk premium.

Moving now to how global factors affect the transmission mechanism as measured by the

exchange rate. Chart 5 decomposes the moves in the Sterling-Dollar exchange rate into

contributions by monetary policy, macroeconomic factors and risks. All other things being

equal, a rise in UK interest rates should cause Sterling to appreciate relative to other

currencies – but we see a marked depreciation instead.

Chart 5: Decomposition of bilateral Sterling-Dollar exchange rate

Cumulative percentage changes

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P, Refinitiv Eikon from LSEG and Bank calculations. Notes: For more

information on the model see Appendix A1. Latest observation: 17

th

February 2023.

The chart covers the entire MPC tightening cycle, and Sterling has depreciated by 10%

versus the Dollar. Up until the end of 2022, the contribution of US policy and

macroeconomic factors have outweighed the MPC’s tightening. This in part reflects the

Federal Reserve tightening, particularly at a quicker pace than the MPC, but also a better

-28

-24

-20

-16

-12

-8

-4

0

4

8

Jan 22 Apr 22 Jul 22 Oct 22 Jan 23

Percent

UK-specific risk-off

UK policy and macro factors

US policy and macro factors

Global risk-on

Cumulative change in GBP/USD

(solid line) and Sterling ERI (dotted)

Bank of England Page 11

macroeconomic outlook in the US. More recently, the orange US bars have come off as

the Fed had been expected to reduce their pace of tightening.

On the other hand, the aqua bars, reflecting the pricing of UK policy and domestic

macroeconomic factors, have increased, suggesting that had the MPC not tightened, the

exchange rate likely would have been even weaker. Another factor weighing on Sterling,

as seen through the lens of this model, is a persistent UK-specific risk premium which

captures the reduced appetite for Sterling assets more broadly, that is, apparently,

unrelated to direct pricing of monetary policy and future macroeconomic conditions.

To summarise this section on the first stage of the transmission mechanism, Chart 6

shows a new measure of aggregate financial conditions in the UK. There are numerous

such indices which all emphasise different aspects of the transmission mechanism. In my

view, this measure is particularly useful as it was constructed by explicitly controlling for

the non-stationarity in many underlying series, so for example should not be affected by a

falling r*. Its average level should, therefore, be able to better capture a notion of “neutral”.

That said, the distinctions among the transmission channels in the decomposition should

not be considered so bright-lined given the endogeneity among the components.

Chart 6: A UK financial conditions index

7

Source: Bloomberg Finance L.P, ICE, Moneyfacts, Refinitiv Eikon from LSEG, Tradeweb and Bank

calculations. Latest observation: January 2023.

7

More information can be obtained in a forthcoming Bank Underground post and in Appendix A2.

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

97 99 01 03 05 07 09 11 13 15 17 19 21 23

Index

Long term interest rates

Short term interest rates

Equity prices

Financial conditions index

£ exchange rate index

Spreads

Bank of England Page 12

This new financial conditions index implies that UK financial conditions are, at the moment,

not much tighter than on average, relative to historical standards. But, coming out of an

entire decade of short rates at the effective lower bound, and relatively loose financial

conditions, we have had to come a long way. We are left with the conundrum of to what

extent tightening or tightness matters for the transmission to the real economy and

inflation.

In my view, we have more to do. Because, as markets have looked forward to the

soon-to-be expected peak in policy rates, financial conditions have again begun to loosen.

Financial conditions are looser relative to what they might be otherwise, due to the

depreciation of Sterling and a falling equity risk premium, which have global factors

embedded in them. To me, as both the level as well as the delta matter in assessing the

effectiveness of transmission of monetary policy, this implies that the forward-looking

nature of financial markets has been absorbing some of the intended tightening, which

impact the long and variable lags of folk wisdom. Even more important is the apparently

premature loosening of conditions, given prospects for inflation formation. A topic to

which I now will turn.

4. The transmission of monetary policy to the real economy and inflation

Now that I have outlined some of the ways in which the transmission through financial

markets can be assessed, I would like to turn the focus to the second stage. The

transmission to the real economy, specifically, inflation.

Measuring the effects of the transmission of monetary policy, or more importantly the

causal effect of monetary policy on the macroeconomy and the price level is challenging.

Not least because the causality runs both ways. Monetary policy can affect the state of the

macroeconomy by changing the interest rate, changing borrowing costs in the economy,

and thereby influencing spending, investment and saving behaviour, including

expectations, wage and price setting. But through the reaction function, monetary policy

will be affected by developments in the macroeconomy: if a central bank observes high

inflation, policymakers should react by setting tighter monetary policy.

Failing to properly account for this empirical modelling challenge resulted in the famous

‘price puzzle’: Empirical models predicted that tightening monetary policy resulted in an

increase, not a decrease in inflation, at least in the short run. Sims (1992) argued this was

because policy shocks used to identify the causal effects also included the endogenous

policy responses to forecasts of future inflation. Ramey (2016) showed that identifying

monetary policy shocks to measure the transmission to macroeconomic outcomes is

Bank of England Page 13

essential in order to estimate causal effects – we require deviations from the monetary rule

to identify the response of the economy to monetary policy.

To confront this endogeneity, we need structural models to estimate the transmission of

monetary policy to the real economy and inflation. Using the results of just one empirical

model as an example, Chart 7 shows the impulse response functions to a 1 percentage

point monetary policy shock, replicated using a method adapted and extended from

Cesa-Bianchi, Thwaites and Vicondoa (2020)

8

. The authors – one of whom is now at the

Resolution Foundation – use a high-frequency identification approach to measure UK

monetary policy surprises, which they use as instruments to identify the transmission to

the real economy. The model is estimated over the entire period of inflation targeting in the

UK excluding the Covid period.

Chart 7: Impulse response functions to a 100 basis point monetary policy shock

Source: Cesa-Bianchi, Thwaites and Vicondoa (2020) and Bank calculations. Notes: sample period

1992-2019, monthly. The solid lines and shaded areas report the median and the 68% confidence intervals,

computed using moving block bootstrap with 5000 replications. For the full set of impulse responses, see

Appendix A3.

Starting by looking at the top left panel, a 100 basis point monetary policy shock has a

persistent effect on the 1-year nominal interest rate, lasting for around twelve months after

the shock hits. The top right-hand panel shows the monetary policy shock also

appreciates the Sterling exchange rate index, with a peak effect at two to three months

8

More information on methodology, and robustness checks can be obtained in Appendix A3.

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

1.5

2

0 4 8 12 16 20 24 28 32 36

1-year nominal interest rate

Percentage points

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

0 4 8 12 16 20 24 28 32 36

Percent

£ exchange rate index

-2.5

-2

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

0 4 8 12 16 20 24 28 32 36

Percent

GDP

-0.5

-0.4

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0

0.1

0.2

0 4 8 12 16 20 24 28 32 36

Percent

CPI

Bank of England Page 14

following the shock, consistent with the effect on the 1-year nominal interest rate. This

follows from the standard theory of interest rate differentials explaining exchange rate

movements when only the home central bank tightens.

The monetary policy shock also has a significant, delayed response on the level of real

GDP, which is consistent with the story on monetary policy lags, but also New Keynesian

theory that GDP lags inflation. Real GDP barely moves on impact, and slowly falls with a

statistically significant peak response of -1.25% after around two years – consistent with

the 18 to 24 months of the long and variable lags story. The results also suggest a

permanently negative effect of contractionary monetary policy on the level of output

relative to trend. This shouldn’t be interpreted as monetary policy scarring activity forever,

as in growth rate space, GDP recovers.

However, the lags on inflation are quite different in this simple set-up. Turning now to the

bottom right panel, the effect on the level of CPI is not only statistically significant and

negative, but also instantaneous. In the model, the fast pass-through of the monetary

tightening likely relies on the exchange rate appreciating on impact.

Of course, this is a simplified version of the world, as the impulse response functions show

the impact of a single monetary policy surprise, and only by UK policymakers, as indicated

by the role for the exchange rate in financial conditions. In reality, the economy has faced

a sequence of these shocks in the past year which have overlapped before we have seen

the full effect of any of them. And, other central banks have also been tightening policy.

Further, the period over which the model was estimated had generally low and stable

inflation. Might these results be affected a period of surging and persistently high inflation

such as we have experienced over the last 18 months? Could high inflation itself affect

the monetary transmission mechanism? Using an event study, Bank researchers show

some evidence for a direct expectations channel of monetary policy which could affect

price setting already within the period of the shock.

9

To examine these questions, I need to

turn to a different kind of model that allows us to control and vary deep parameters about

expectations formation.

9

See Di Pace et al. (2023) who analyse firm expectations in particular, and find that announced changes in

the monetary policy rate induce firms to revise their price expectations, with rate hikes inducing a decrease

in price expectations and uncertainty surrounding them.

Bank of England Page 15

5. A stylised example of forward- versus backward-looking expectations

formation and the monetary policy transmission mechanism

This section presents a so-called “toy model” in which we can vary the share of

backward-looking price-setters in the economy. At its core, it is a very simple, calibrated,

textbook New Keynesian model.

10

It is designed to capture a certain mechanism that we

are interested in but, as these models tend to do, it disregards many other features of the

real world. It shouldn’t be thought of as quantifying the behaviour of any particular real-life

economy. For example, it is not COMPASS, the Bank’s large and complex structural

model that is used, among others, in our forecasting exercise every quarter (Burgess et al,

2013). Although, as a dynamic and stochastic general equilibrium model, it does share the

underlying modelling paradigm.

This model focuses and formalises a concern that I flagged in a previous speech

(Mann, 2022b): What happens to the behaviour of macroeconomic aggregates if people

begin to form backward-looking inflation expectations? In this model, I find that, indeed, a

higher degree of “backward-lookingness” generates more inflation persistence even if the

underlying shock is the same. But, crucially, it also changes the effectiveness of monetary

policy to control inflation. A given monetary tightening has less of an effect on inflation if

expectations formation is mainly backward-looking, detached from demand and supply

conditions, which thereby worsens any inflation-activity trade-off in the face of a shock.

Stepping back from the model exercise, is there evidence that the degree of forward- and

backward-lookingness changes? In a previous speech (Mann, 2022b), I cited research

which estimated the share of forward- versus backward-looking agents using switching

forecast rules. Cornea-Madeira and Madeira (2022) show empirically that for the UK the

share of backward-looking agents has varied significantly over time, in particular being

higher when energy prices surge.

11

Returning to the model, we can trace out the response of our model economy to the same

underlying shock: a so-called cost-push shock which exogenously increases prices over

and above what would be implied by domestic demand conditions. It is, of course,

intended to stand in for the global goods price shock of 2021 or the energy price shock of

2022.

10

It is a generalisation of the model described in Chapter 3 of Galí (2015), enriched with backwards- and

forward-looking price-setters as in Galí and Gertler (1999). For more information, please see Appendix 4.

11

For a fully structural model with endogenous forecast switching, see Fischer (2022).

Bank of England Page 16

Consider Chart 8: it shows the reactions for a model economy which differs only by the

share of backward-looking price-setters.

12

The baseline, where all firms form fully

forward-looking and model-consistent expectations, is shown in the aqua line. In this

economy, the cost-push shock has a very limited and short-lived impact on activity and

prices. The output gap jumps on impact but quickly returns to zero. Because of the lagged

nature of year-on-year inflation (Mann, 2023), it peaks after four quarters and then reverts

towards target.

Chart 8: Responses to an inflationary cost-push shock, given a central bank

using a balanced Taylor Rule

Output gap (LHS) and year-on-year inflation (RHS)

Source: Bank calculations. Notes: Responses are generated using a New Keynesian model with varying

degrees of backward-looking expectations formation. For more information, see Appendix A4.

The behaviours of the output gap and inflation change dramatically when we introduce a

modest degree of backward-looking inflation expectations formation. The output gap is

more negative for longer which is mirrored in inflation peaking higher and remaining above

target for an extended period of time.

Increasing the share of backward-looking agents even more takes this pattern to the

extreme. Both output and inflation display a pronounced hump-shaped pattern and are

away from equilibrium for the entirety of the plotted period (4 years). Remember that I

12

The three lines refer to models in which the share of backward-looking firms is calibrated to be zero, 40,

and 80 percent respectively. The choice of these values, away from the fully forward-looking baseline, is

motivated by the range of the share of fundamental agents in Cornea-Madeira and Madeira (2022) which

find that for most of the last 50 years, this share has fluctuated between 20 and 80 percent with a median of

about half.

-2

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

Quarters after shock

Many backward-

looking firms

Fully forward-looking

baseline

Few backward-

looking firms

Percentage points

-2

0

2

4

6

8

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

Quarters after shock

Many backward-

looking firms

Fully forward-looking

baseline

Few backward-

looking firms

Percentage points

Bank of England Page 17

have not changed the size of the shock – just the degree of backward-lookingness of the

firms in the economy.

These pictures also reveal an important non-linearity generated by changes in the

formation of inflation expectations. Even though I have increased the share of

backward-looking firms by equally sized increments step-by-step from aqua to orange to

purple, the change in behaviour is increasingly stark. Not only does more

backward-lookingness worsen the trade-off between inflation and output, every additional

step worsens the trade-off by more than the last.

The outcomes in the previous charts are determined also by what central banks are doing.

Chart 9 shows the nominal (left side) and real interest (right side) rates associated with the

central bank that follows a Taylor rule balanced between output and inflation deviations

from target. In the model, this trade-off is reflected in the reaction of interest rates to the

shock.

Chart 9: Responses to an inflationary cost-push shock, given a central bank

using a balanced Taylor Rule

Annualised nominal (LHS) and real interest rates (RHS)

Source: Bank calculations. Notes: Responses are generated using a New Keynesian model with varying

degrees of backward-looking expectations formation. For more information, see Appendix A4.

In the baseline case with fully forward-looking agents, the central bank raises nominal

rates on impact which, due to benign inflation dynamics is sufficient to raise the real rate,

which dampens inflation, and quickly both interest rates (and the real economy and

-2

0

2

4

6

8

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

Quarters after shock

Many backward-

looking firms

Fully forward-looking

baseline

Few backward-

looking firms

Percentage points

-2

-1.5

-1

-0.5

0

0.5

1

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

Quarters after shock

Many backward-

looking firms

Fully forward-looking

baseline

Few backward-

looking firms

Percentage points

Bank of England Page 18

inflation) return to baseline. In the two less benign cases, however, despite the central

bank raising the nominal rate sharply and persistently, the real rate actually falls initially.

Since it is the real rate that determines output in this model, the falling real rate adds to

inflation persistence so that, in the latter half of the simulation, the central bank must keep

restrictive real rates longer in order to stabilise the economy. In the case of many

backward-looking firms, the nominal interest rate rises even more and the restrictive real

rates last for much longer.

However, the problems of the central bank in the orange or the purple economy do not

stop there. As a result of the increased share of backward-looking firms, the speed at

which monetary policy can affect realised inflation also changes. In other words, the lags

of the monetary transmission mechanism lengthen as shown by the increasingly long

period away from the neutral line in the charts, which is particularly dramatic for the purple

economy. The share of backward-looking firms in the purple economy is 80%, which is

what Cornea-Madeira and Madeira (2022) find in their work for years when energy prices

surged.

13

Finally, given the monetary response, what happens to inflation? Chart 10 plots the

inflation response to a monetary policy shock in the three types of economies. All three

lines are indexed to yield the same amount of output losses. As shown in the appendix

(Chart A4.2), the path for output and the nominal interest rate is very similar for each

case, which implies that the monetary transmission mechanism into economic activity is

not meaningfully affected by backward-looking inflation expectations.

13

In this simple model, we abstract from the behaviour of financial conditions discussed above. In that

sense, the model here simplifies away the challenges of transmitting monetary policy through financial

markets, the focus of the first half of the speech.

Bank of England Page 19

Chart 10: Inflation responses to a contractionary monetary policy shock, given

same output costs

Year-on-year inflation

Source: Bank calculations. Notes: Responses are generated using a New Keynesian model with varying

degrees of backward-looking expectations formation. For more information, see Appendix A4.

However, what does change is the transmission of monetary policy into prices. By

construction, in the chart, the tightening yields the same outcome in activity, so we can

read the lines as a dynamic slope of the Phillips curve under conditions of changing

expectations formation.

14

An increasing degree of backward-lookingness implies a

shrinking share of price-setters in the economy that consider supply and demand

conditions when making decisions. Therefore, their importance for aggregate inflation

falls. Inflation becomes persistent because firms that set prices and generate inflation

expect it to be persistent. With a high share of backward-looking agents, monetary policy

effectiveness – whether directly on expectations or through the output gap channel – is

greatly diminished.

What does the central banker need to do when faced with these different types of

expectations formation? The model in Chart 9 shows the extent to which monetary policy

needs to be increasingly restrictive to return the inflation rate to target when agents

increasingly are backward-looking.

We have to remember that the world has been hit by a sequence of large inflationary

shocks, which have increased the risk of being in the purple world in which troubling

14

It is also related to the Phillips multiplier of Barnichon & Meesters (2021) in that it attempts to capture the

trade-off between inflation and economic activity over time.

-0.3

-0.2

-0.1

0

0.1

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

Percent

Quarters after shock

Many backward-

looking firms

Fully forward-looking

baseline

Few backward-

looking firms

Bank of England Page 20

non-linearities are evident. I am not saying we are at that point yet or that we will

necessarily get there given what we know now. However we need to be aware of how

important the expectations formation process is for the effectiveness of monetary policy,

and position ourselves accordingly. To reduce the risk of ending up in the ‘purple’ world,

we should weigh inflation more highly in our reaction function.

15

6. What does this all mean for monetary policy?

So, what does this all mean for monetary policy? Typically, we assume that the world is

sufficiently stable such that the estimated relationships between, for example Bank Rate

and inflation also are stable and we can look to these when deliberating monetary policy

stance – the folk wisdom of 18 to 24 months.

In this speech, I have presented state-of-the-art evidence which shows that, in normal

times, the monetary transmission into inflation is in fact faster, peaking within the first year.

But, I have also reviewed factors that may change these relationships – change the long

and variable lags – including a) that there has been a sequence of shocks, b) that the

transmission from monetary policy to financial markets has been quick, but not all in the

direction of tightening, and c) that the degree of backward- or forward-lookingness in

expectations formation influences the effectiveness of monetary policy. Going forward,

how should this reassessment of lags determine the appropriate monetary policy strategy?

Looking back to my speech from just under a year ago (Mann, 2022a), in the face of two

shocks, and given what was already in-train regarding inflation expectations and the

collected research on policy effectiveness in the face of inflation uncertainties, a greater

degree of front-loading would have reduced the risk of an increasing share of

backward-looking households and firms.

In the end, monetary policy has taken a path which has been historically aggressive, but

perhaps insufficiently so relative to the multiple shocks, the behaviours pushing up

inflation, and the initial accommodative starting point. The stage was set for a

transmission of monetary policy to financial markets that has been quick, but also has

been partially absorbed. And also, having a shorter horizon and being more

15

Indeed, in an exercise of explicitly considering overlapping shocks and monetary reaction, I evaluate the

implied paths of inflation and the output gap according to the loss function of Mark Carney’s “Lambda”

speech of 2017. In that speech, he shows how this loss function can embody society’s preferred trade-off.

Given the shocks hitting our model economy, the inflation-biased policy rule delivers a combination of output

and inflation which is superior to those of the balanced policy rule.

Bank of England Page 21

forward-looking than households and firms, markets are already incorporating the

expected future inflection in monetary stance.

Collectively, all this adds up to financial conditions that are now looser than what likely will

be needed to moderate the embedding of on-going inflation into the wage- and

price-setting paths. I worry that this constellation could yield extended persistence of

inflation into this year and the next. The resulting long period of time above the 2% target

could increase the degree of backward-lookingness, or catch-up behaviour, in the system.

Given that the risk of increasingly persistent inflation rises disproportionately with the share

of backward-lookingness, I believe that more tightening is needed, and caution that a pivot

is not imminent. In my view, a preponderance of turning points (Mann, 2023) is not yet in

the data.

We have an inflation remit, and we will achieve it one way or another. Failing to do enough

now risks the worst of both worlds – the higher inflation and lower activity of the ‘purple’

regime – as monetary policy will have to stay tighter for longer to ensure that inflation

returns sustainably back to the 2% target.

The views expressed in this speech are not necessarily those of the Bank of England or

the Monetary Policy Committee.

I would like to thank in particular Lennart Brandt and Natalie Burr, as well as

Andrew Bailey, Nicolò Bandera, Lauren Barnes, Robin Braun, Alan Castle,

Matthieu Chavaz, Ambrogio Cesa-Bianchi, Johannes Fischer, Maren Froemel,

Robert Hills, Huw Pill, Silvana Tenreyro, and Chris Yeates for their comments and help

with data and analysis.

Bank of England Page 22

References

Barnichon, R. and G. Meesters (2021). ‘The Phillips multiplier’, Journal of Monetary

Economics, 117, pp. 689-705.

Burgess, S., E. Fernandez-Corugedo, C. Groth, R. Harrison, F. Monti, K. Theodoridis and

M. Waldron (2013). ‘The Bank of England’s forecasting platform: COMPASS, MAPS,

EASE and the suite of models’, Working Paper No. 471.

Busetto, F., M. Chavaz, M. Froemel, M. Joyce, I. Kaminska and J. Worlidge (2022). ‘QE at

the Bank of England: a perspective on its functioning and effectiveness’, Quarterly

Bulletin 2022 Q1.

Calza, A. and J. Sousa (2005). ‘Output and inflation responses to credit shocks. Are

there threshold effects in the euro area?’, Working Paper Series No. 481.

Carney, M. (2017). ‘Lambda’, speech given at London School of Economics.

Cesa-Bianchi, A., G. Thwaites and A. Vicondoa (2020). ‘Monetary policy transmission

in the United Kingdom: a high frequency identification approach’, European

Economic Review, 123.

Choi, J., T. Doh, A. Foerster and Z. Martinez (2022). ‘Monetary Policy Stance is Tighter

than Federal Funds Rate’, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco Economic Letter.

Cornea-Madeira, A. and J. Madeira (2022). ‘Econometric Analysis of Switching

Expectations in UK Inflation’, Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 84 (3), pp.

651 – 673.

Di Pace, F., G. Mangiante and R. Masolo (2023). ‘Do firm expectations respond to

monetary policy announcements?’, Staff Working Paper No. 1014.

Dison, W. and A. Rattan (2017). ‘An improved model for understanding equity prices’,

Quarterly Bulletin 2017 Q2

European Central Bank (n.d.). 'Transmission mechanism of monetary policy'

Friedman, M. (1961). ‘The Lag in Effect of Monetary Policy’, Journal of Political

Economy, 69 (5), pp. 447-466.

Mann, C. L. (2022a). ‘A monetary policymaker faces uncertainty’, speech given at a

Bank of England webinar.

Bank of England Page 23

Mann, C. L. (2022b). ‘Inflation expectations, inflation persistence, and monetary

policy strategy’, speech given at the 53rd Annual Conference of the Money Macro and

Finance Society.

Mann, C. L. (2023). ‘Turning Points and Monetary Policy Strategy’, speech given at the

Lámfalussy Lectures Conference in Budapest, Hungary.

Ramey, V. A. (2016). 'Chapter 2 - Macroeconomic shocks and their propagation’ in

Taylor, J. B. and H. Uhlig (2016) ‘Handbook of Macroeconomics’, 2, pp. 71-162.

Sims, C. A. (1992). ‘Interpreting the macroeconomic time series facts: The effects of

monetary policy’, European Economic Review, 36 (5), pp. 975-1000.

Woodford, M. (2005). ’Central Bank Communications and Policy Effectiveness’,

Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium Paper.

Wu, J. C. and F. D. Xia (2016). ‘Measuring the Macroeconomic Impact of Monetary

Policy at the Zero Lower Bound’, Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 48 (2-3), pp.

253-291.