GUIDANCE IN THE RULEMAKING

PROCESS: EVALUATING PREAMBLES,

REGULATORY TEXT, AND

FREESTANDING DOCUMENTS AS

VEHICLES FOR REGULATORY

GUIDANCE

Kevin M. Stack

Professor of Law and Associate Dean for Research

Vanderbilt University Law School

FINAL REPORT

May 16, 2014

*This report was prepared for the consideration of the Administrative Conference of the United States. The views

expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the members of the Conference or its

committees.

ADMINISTRATIVE CONFERENCE

OF THE UNITED STATES

ii

Contents

Contents .................................................................................................................................................................. ii

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................. 1

I. Definition of Guidance and Scope of Inquiry .......................................................................................... 4

A. Definition and Dimensions of Guidance ...................................................................................................4

B. Scope of Inquiry and Methodology ..........................................................................................................6

II. Guidance and Rulemaking: A Brief Overview ........................................................................................ 7

A. The APA’s Vision: The Dual Role of the Statement of Basis and Purpose -- Justification and

Guidance ...................................................................................................................................................7

B. The Expanding Preamble, Ossification, and Separately Issued Guidance ...............................................9

III. The Law Governing Contemporaneous Guidance ................................................................................. 13

A. Process Requirements for Issuing Contemporaneous Guidance ............................................................14

B. Process Requirements for Revising Contemporaneous Guidance: The Impact of Alaska

Professional Hunters ..............................................................................................................................16

C. When Is Contemporaneous Guidance Subject to OIRA Review? ..........................................................18

D. What Contemporaneous Guidance is Required? ....................................................................................19

E. What May Not Be Included in Contemporaneous Guidance? ................................................................22

F. Reviewability of Contemporaneous Guidance .......................................................................................25

G. Standard of Judicial Review ...................................................................................................................27

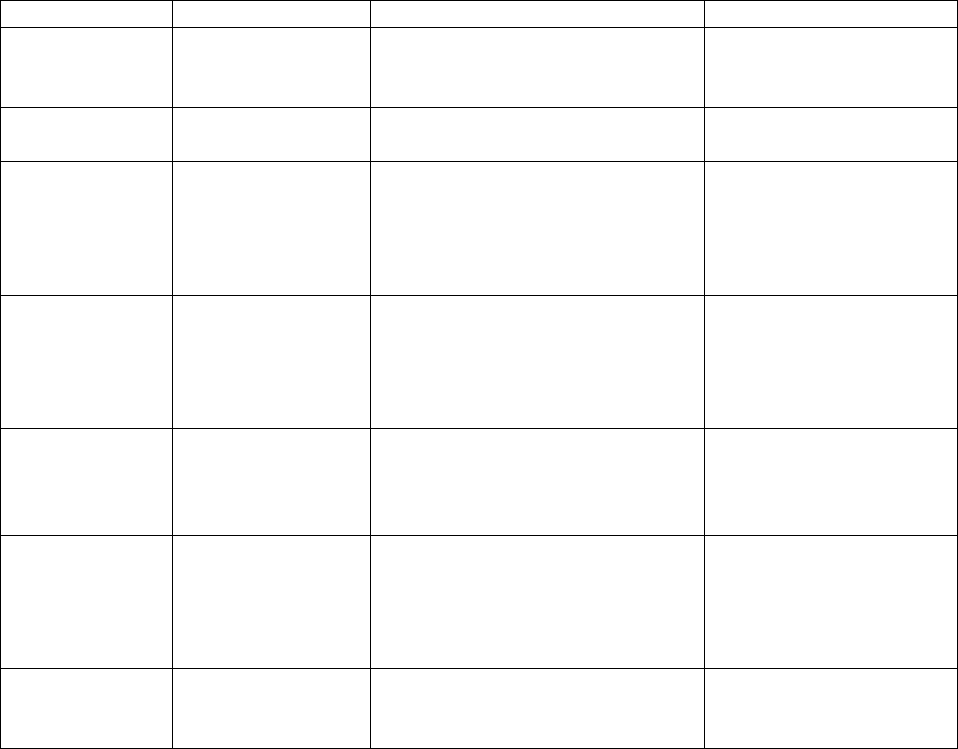

H. Summary Table .......................................................................................................................................30

IV. Agency Practices for Providing Contemporaneous Guidance ............................................................... 31

B. Preambles as a Vehicle for Guidance .....................................................................................................34

C. Guidance in Regulatory Text and Appendices .......................................................................................41

D. Separately Issued Contemporaneous Guidance ......................................................................................46

V. Recommendations to Federal Agencies ................................................................................................. 47

1

Introduction

In the past two decades, the use of guidance—nonbinding statements of

interpretation, policy, and advice about implementation—by administrative agencies has

prompted considerable interest from executive branch officials, committees in Congress,

agency officials, and commentators. Most of this attention has been directed toward

“guidance documents,”

1

freestanding, nonbinding policy and interpretive statements issued

by agencies. Policymakers and commentators have expressed concern that agencies are

relying on guidance documents in ways that circumvent the notice-and-comment

rulemaking process; in particular, the worry is that with the increased analytical and

justificatory burdens of notice-and-comment rulemakings, agencies have turned to

guidance as a way to establish norms without the participation benefits and explanatory

burdens of the notice-and-comment process.

2

1

OFFICE OF MANAGEMENT AND BUDGET, FINAL BULLETIN FOR AGENCY GOOD GUIDANCE PRACTICES, 72

FED. REG. 3432, 3439 (Jan. 25, 2007) (defining a “guidance document” as “an agency statement of general

applicability and future effect, other than a regulatory action . . . that sets forth a policy on a statutory,

regulatory or technical issue or an interpretation of a statutory or regulatory issue.”) [hereinafter OMB’s

Good Guidance Bulletin].

2

For instance, in 1992, the Administrative Conference of the United States (ACUS) recommended that

agencies provide affected persons an opportunity to challenge the wisdom of a guidance document or policy

statement before the statement is applied to persons affected. Admin. Conf. of the United States, Agency

Policy Statements, Recommendation 92-2, 57 Fed. Reg. 30,103 (June 18, 1992). The ACUS

Recommendation commented, “The Conference is concerned . . . about situations in where agencies issue

policy statements which they treat or which are reasonably regarded by the public as binding . . . .[but these

pronouncements do] not offer the opportunity for public comment . . .”). In 2007, President Bush issued an

executive order which subjected significant guidance documents to regulatory review based on similar

concerns. See Exec. Order No. 13,422, 3 C.F.R. § 191 (2008). President Obama revoked Executive Order

14,422, see Exec. Order No. 13,497, 3 C.F.R.§ 218 (2010), but as discussed below, see Memorandum from

Peter Orzag, Dir. Office of Mgmt. & Budget, to Heads and Acting Heads of Exec. Dep’ts and Agencies

(Mar. 4, 2009) [hereinafter “Orzag Memorandum”] (available at

http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/ memoranda_fy2009/m09-13.pdf), significant

guidance is still subject to regulatory review. In 2007, OMB issued a “Final Bulletin for Agency Good

Guidance Practices” which requires agencies to provide a means for comment on certain significant guidance

documents, see OMB’s Good Guidance Bulletin, supra note 1, and this Bulletin remains in effect.

Committees in Congress have expressed concerns that agencies are inappropriately relying on guidance. See,

e.g., COMM. ON GOV’T REFORM, 106TH CONG., NON-BINDING LEGAL EFFECT OF AGENCY GUIDANCE

DOCUMENTS, H.R. REP. NO. 106-1009, at 9 (2000) (“[A]gencies have sometimes improperly used guidance

documents as a backdoor way to bypass the statutory notice-and-comment requirements for agency

rulemaking . . .”); cf. The Regulatory Accountability Act of 2013, S. 1029, 113th Cong. (2013) (Section

706(d) would overrule Auer deference to agency interpretations of their own regulations); Todd D. Rakoff,

The Choice Between Formal and Informal Modes of Administrative Regulation, 52 ADMIN. L. REV. 159, 166

(2000) (arguing that agencies are avoiding ossified rulemaking process by use of nonbinding guidance). For

a concise overview of the legal and policy debates over guidance documents, see Nina A. Mendelson,

Regulatory Beneficiaries and Informal Agency Policymaking, 92 CORNELL L. REV. 397, 397-414 (2007). As I

discuss below, recent empirical research calls into question empirical basis for the theory of strategic

substitution of guidance documents for rules. See infra Part II.B.

2

Concern about agency reliance on guidance is also evident in the Supreme Court’s

doctrines governing the standards of judicial review of agency action. Based in part on the

preference for policy formulation through rulemaking and other more formal processes, in

2001, the Supreme Court announced a general presumption that to qualify for Chevron

deference,

3

agency interpretations of the statutes the agency administers must be issued

through relatively formal processes, such as notice-and-comment rulemaking.

4

That 2001

decision, United States v. Mead Corp.,

5

gives agencies incentives to act through notice-

and-comment as opposed to guidance documents if they seek to trigger Chevron deference

in review of their actions. In addition, in the last two years, three members of the Supreme

Court have announced their interest in reconsidering the longstanding doctrine identified

with Bowles v. Seminole Rock & Sand Co.

6

and Auer v. Robbins,

7

under which the

reviewing courts must accept agency interpretation of their regulations unless plainly

erroneous or inconsistent with the regulation.

8

In the same time period, the Supreme Court

denied deference to an agency interpretation of its own regulation that appeared in a

litigation brief.

9

These decisions suggest a narrowing of deference available to agencies

when they take interpretive positions or issue guidance informally and post hoc.

This multi-decade debate about guidance and its relationship to notice-and-

comment rulemaking has largely passed over the function and varieties of

contemporaneous guidance—that is, guidance that agencies provide about the meaning of

their rules in the rulemaking process. Contemporaneous guidance appears in three main

forms. First, agencies provide guidance about the meaning and application of their rules in

explanatory “statement[s] of their basis and purpose,”

10

statements which constitute the

bulk of the regulatory “preambles” issued with final rules. Second, they provide guidance

about the application and interpretation of their regulations in the Code of Federal

Regulations, in notes and examples, and appendices to rules that are published in the Code

3

Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, 467 U.S. 837, 843-44 (1984).

4

United States v. Mead Corp., 533 U.S. 218, 230-31 (2001) (noting that agency decisions decided in notice-

and-comment qualify for review under Chevron).

5

Id.

6

325 U.S. 410 (1945).

7

519 U.S. 452 (1997). While this doctrine was traditionally associated with Seminole Rock, since 1997 the

Supreme Court and other courts have frequently attributed it to Auer, see, e.g., Talk Am., Inc. v. Mich. Bell

Tel. Co., 131 S. Ct. 2254, 2265–66 (2011) (Scalia, J., concurring) (noting that the Seminole Rock doctrine has

recently been attributed to Auer), despite the fact that Auer involved a straightforward application of

Seminole Rock, see Auer, 519 U.S. at 461 (relying on Seminole Rock with little ado).

8

Decker v. Northwest Envt’l Def. Center, 133 S. Ct. 1326 (2013); id. at 1338 (Roberts, C.J., and Alito, J.,

concurring) (noting that it “may be appropriate to reconsider” Seminole Rock/Auer in another case); id. at

1339, 1442 (Scalia, J.) (concurring in part and dissenting in part) (urging the Court to overturn Seminole

Rock/Auer).

9

See Christopher v. SmithKline Beecham Corp., 132 S. Ct. 2156, 2166–68 (2012) (concluding that “general

rule” of granting Auer deference to interpretations in litigation briefs did not apply in these circumstances of

the case in view of fair notice concerns).

10

5 U.S.C. § 553 (2012).

3

of Federal Regulations. Third, at the same time that agencies promulgate their regulations,

they sometimes issue freestanding guidance documents. Contemporaneous guidance has a

fundamental fair-notice benefit: It furnishes the public and regulated entities the agency’s

understanding of the regulation at the time of issuance, reducing some of the uncertainty

incident to any new regulatory change, as opposed to later in time or in the context of an

enforcement proceeding.

11

The neglect of contemporaneous guidance in debates about guidance practices and

rulemaking has practical implications along four dimensions. First, and at a most basic

level, there has been little dialogue among policymakers or commentators about the best

practices for providing guidance in the rulemaking process. Agencies have adopted a

diverse set of practices. While uniformity is not necessary or a value to unreflectively

demand of a practice as diverse and wide-ranging as rulemaking, the self-conscious

choices that some agencies make about how to issue contemporaneous guidance can be a

source of information and insight to other agencies. One aim of this Report is to catalogue

the variety of agency practices, and legal regime that governs them, as a prompt to

reflection about those that best suit particular rulemaking environments.

Second, while many agencies openly embrace the guidance function of preambles,

other agencies treat their preambles as unrelated to, and performing an entirely different

function than, their “guidance documents.” But by treating preambles as occupying a

functionally and conceptually distinct silo from guidance, some agencies neglect the basic

guidance function of the “statement of [] basis and purpose,” exclude preambles from their

general policies on guidance, fail to include reference to preambles in their official

compilations of guidance, and web postings of guidance. Many agencies could also do

more to make guidance they provide in preambles easier to locate, for instance, by

organizing them to make it easier for the reader to locate the most salient discussions of

each element of the regulation, limiting the extent to which they rely on discussions of the

rule in notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) which can require the reader to integrate

two separate statements of the rule, and/or by including hyperlinks to the preambular

guidance on electronic versions of their regulatory texts. A second aim of this Report is to

suggest reasons why contemporaneous guidance deserves a place at the table in debates

and agency choices about guidance practices and rulemaking, and to make several specific

supporting recommendations in this regard.

11

This is not to say that a broad variety of circumstances—uncertainty about how a regulation will affect

those subject to it, changes in technological, business, environmental or other conditions, newly acquired

expertise or studies, constraints on agency staff time, etc.—all provide a justification for issuing post hoc

guidance. But if all other considerations are equal, contemporaneous guidance has a fair notice benefit.

4

Third, at the other extreme, in some cases, agencies treat the text of their preambles

and the text of their rules as functional equivalents. Thinking about preambles as a source

of guidance also prompts inquiry into the boundaries of appropriate use of the preamble.

A third aim of the Report is to identify the residual need to insist on the distinctions

between preamble and regulatory text.

Fourth, agencies have unrealized opportunities for including notes and examples in

the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) or more extensive guidance published as

appendices to the CFR. Where the agency knows that the regulated public relies primarily

on the CFR to understand its obligations, there is a strong need for uniformity in guidance,

and that guidance does not need to be frequently amended including notes and examples in

the CFR or more extensive guidance in an appendix to the CFR can enhance the visibility

of this agency advice. The Report also seeks to identify some of those opportunities.

This Report is organized as follows. Part I defines guidance and discusses the

scope of the inquiry and methodology of the Report. Part II gives a brief overview of

notice-and-comment rulemaking and the role of guidance in the rulemaking process. Part

III describes the legal regime governing guidance in preambles, regulatory text, and

contemporaneous, separately issued documents. The summary provided in Part III

illustrates the continuities between guidance issued in a preamble, regulatory text, and

separate documents, highlighting the need for self-conscious choice by agencies about the

forms in which they issue guidance. Part IV offers a description of the varieties of

contemporaneous guidance that agencies issue. Part V makes several recommendations to

federal agencies. Given that regulations have long since outnumbered statutes,

12

it is worth

examining the promise and challenges that contemporaneous guidance faces.

I. Definition of Guidance and Scope of Inquiry

A. Definition and Dimensions of Guidance

It is first important to define what is meant by the word “guidance” in this Report.

By “guidance” this Report refers to (i) agency statements outside of those appearing in

regulatory text that pertain to the meaning or interpretation of the agency’s regulations or

to advice about how to comply with the agency’s regulations, and (ii) agency statements

12

See CORNELIUS M. KERWIN & SCOTT P. FURLONG, RULEMAKING: HOW GOVERNMENT AGENCIES WRITE

LAW AND MAKE POLICY 13-21 (4th ed. 2011) (documenting, in both number of rules and pages of the

Federal Register devoted to federal regulations, a level of production that far exceeds comparable measures

for federal legislation).

5

appearing in regulatory text that are designed to guide the application or interpretation of

the regulation, such as examples or official commentaries.

This definition departs from the most prominent definition of guidance which

appears in the Office of Management and Budget’s Final Bulletin on Agency Good

Guidance Practices (“OMB’s Good Guidance Bulletin”)

13

in two important respects.

Under OMB’s Good Guidance Bulletin, a “guidance document” is “an agency statement of

general applicability and future effect, other than a regulatory action, that sets forth a

policy on a statutory, regulatory or technical issue or an interpretation of a statutory or

regulatory issue.”

14

In contrast, this Report addresses only guidance about the meaning or

application of regulations, not guidance about statutes or other sources of law. In that

respect, this Report focuses on a narrower class of guidance that falls within the Bulletin’s

definition.

Second, this Report includes statements that appear in the regulation’s text or are

published in an appendix to the regulation’s text as forms of guidance. Because some of

these statements might qualify as “regulatory action[s]” under OMB’s Good Guidance

Bulletin’s definition of guidance, they would be excluded from its scope.

Because

statements that are similar in content can appear in a regulation’s preamble, text, or a

separately issued document, the broader definition used in this Report does not preclude

consideration of these forms of guidance, and agencies’ justifications for using them. But

because “guidance” is so frequently associated with documents issued outside of

rulemaking, it is worth expressly emphasizing that under the definition of “guidance” used

here, the guidance may appear in a preamble or the text of a regulation, not merely in

separately issued documents.

15

With guidance so defined, guidance can be classified on three dimensions:

1. Timing. Guidance can be provided at the time of the regulation’s issuance

or at a later time. Contemporaneous guidance would include guidance that appears in a

13

OMB’s Good Guidance Bulletin, supra note 1. The definition of “guidance document” adopted in OMB’s

Good Guidance Bulletin is the same as that used in President Bush’s Executive Order, Further Amendments

to Executive Order 12866 on Regulatory Planning and Review, Executive Order 13,422, 72 Fed. Reg. 2763,

2762 (Jan. 23, 2007) (inserting Section 3(g) with this definition), which President Obama revoked. See Exec.

Order No. 13,497, 3 C.F.R. § 218 (2010).

14

See OMB’s Good Guidance Bulletin, supra note 1, at § I.3.

15

It is worth also emphasizing that statements in preambles could be considered guidance documents even

under the definition of guidance in OMB’s Good Guidance Bulletin because they are “an agency statement[s]

of general applicability and future effect, other than a regulatory action, that sets forth a policy on a . . .

regulatory or technical issue or an interpretation of . . . a regulatory issue.” Id.

6

preamble, the regulation’s text, or documents issued at the same time as the regulation,

such as compliance guides.

16

All other guidance is post hoc.

2. Content. Guidance can take innumerable forms, including: providing (1)

general advice about the meaning of particular words or provisions, (2) answers to

frequently asked questions, (3) announcement of priorities of the agencies with regard to

the enforcement of their regulations, (4) examples of calculations required under the

regulations, and (5) examples of model forms.

3. Location. As noted above, guidance can also appear as part of different

documents, most obviously including: (1) the regulation’s preamble, (2) portions of the

agency’s reasoning stated in a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) adopted in the

regulation’s preamble, (3) the regulation text, such as in notes and examples, (4) an

appendix to the regulation’s text whether published in the Code of Federal Regulations

(CFR) or not, or (5) documents issued separately from these core rulemaking documents.

B. Scope of Inquiry and Methodology

This Report focuses on this third dimension—the location of guidance. In almost

every rulemaking, agencies face a choice regarding guidance. They can issue virtually

identical advice and text in the regulation’s preamble, the regulation’s codified text or

appendix, or in a separate document issued alongside the rule; guidance that appears in

preambles in some rulemakings appears in regulatory text or separately issued documents

in other rulemakings. The variation is not itself a cause for concern; the difference in the

content of regulations, their audience, duration, and interaction with the surrounding legal

landscape among many other factors may justify these different choices, even for a single

agency. But because these different locations can have different legal effects, different

modes of publication, and different ability to reach the regulated, it is worth examining the

constraints on the agency’s choices and the considerations that inform their best practices

with regard to issuing contemporaneous guidance. Those questions are the focus of this

Report.

The Report was conducted primarily through legal research and research on

agencies’ practices in providing contemporaneous guidance. As to agency practices, the

research had two components. First, it involved text-based word searches of rulemakings

conducted in the last five years by executive agencies that had promulgated economically

16

Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act, Pub. L. No. 104-121, § 212(a), 110 Stat. 873,

codified at 5 U.S.C. § 601 nt. (2012).

7

significant regulations in the last 15 years. The focus on the last five years was to ensure

study of current practices. The set of executive agencies that had issued an economically

significant rule in the last 15 years is drawn from David Lewis and Jennifer Selin’s

Sourcebook of the United States Executive Agencies.

17

This sample was chosen because it

reflects a cross-section, at least of executive agencies, engaged in the most significant

rulemakings. Second, with the assistance of Staff Counsel at the Administrative

Conference of the United States (ACUS), I also conducted half-hour phone interviews with

counsel working on rulemaking in 12 agencies in January and February, 2014.

18

The

Report includes discussion of examples of rulemakings from those agencies even if they

were not among those identified for the word searches of agency practices. On February

10, 2014, I presented an overview of the project for brown bag discussion at ACUS

headquarters attended by more than thirty other government lawyers working on

rulemaking. The experience and insight of the lawyers with whom I spoke informed the

recommendations and coverage of this Report.

II. Guidance and Rulemaking: A Brief Overview

To assess the appropriate role of guidance in rulemaking today, it first makes sense

to begin with some background understanding of the place and prominence of guidance

within and outside of notice-and-comment rulemaking proceedings.

A. The APA’s Vision: The Dual Role of the Statement of Basis and

Purpose -- Justification and Guidance

The Administrative Procedure Act (APA) provides a simple structure for notice-

and-comment rulemaking, especially given the scope of federal lawmaking that now

emerges through this process. Section 553 of the APA sets out three basic elements of

notice-and-comment rulemaking.

19

First, section 553 requires publication of a “[g]eneral

notice of proposed rulemaking” in the Federal Register, commonly referred to as an

17

DAVID E. LEWIS & JENNIFER L. SELIN, SOURCEBOOK OF UNITED STATES EXECUTIVE AGENCIES 132 (Table

20) (December 2012 First Edition). The following agencies fall in this category: USDA, DOC, DOD,

DOED, HHS, DHS, HUD, DOI, DOJ, DOL, STAT, DOT, DTRS, DVA, EPA, EEOC, OMB, OPM, RRB,

SBA, and SSA.

18

These agencies included the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Consumer Financial

Protection Bureau, Department of Education, Department of Health and Human Services, Department of the

Interior, Department of Transportation, Department of the Treasury, Equal Employment Opportunity

Commission, Merit Systems Protection Board, Occupational Health & Safety Review Commission, Social

Security Administration, and U.S. Coast Guard.

19

5 U.S.C. § 553 (2012). Section 553 provides a default process for rulemaking except in the rare case of a

statute that requires the rulemaking be conducted through the APA’s formal rulemaking procedure, see id. §

553 (noting that § 556 & § 557 apply when the rules are required by statute “to be made on the record and

after opportunity for an agency hearing”), or when a statute specifies its own rulemaking procedure.

8

“NPRM.”

20

Second, after publication of that required notice, the agency “shall give

interested persons an opportunity to participate in the rule making through submission of

written data, views, or arguments.”

21

Third, after consideration of these comments, “the

agency shall incorporate in the rules adopted a concise and general statement of their basis

and purpose.”

22

The APA exempts from these notice and consideration requirements

“interpretative rules, general statements of policy, or rules of agency organization,

procedure, or practice,” among other exceptions, which are sometimes referred to as

nonlegislative rules or guidance documents.

23

Early understandings of the APA suggest that the statement of basis and purpose,

which comprises much of what is commonly referred to as the regulation’s “preamble,”

was intended to have a dual role: not only identifying the legal and factual basis for the

rule, but also providing guidance on its meaning and import for the public and the courts.

This message comes through clearly in the Attorney General’s Manual on the

Administrative Procedure Act.

24

Of the statement of basis and purpose, the Manual opines,

“[t]he required statement will be important in that the courts and the public will be

expected to use such statements in the interpretation of the agency’s rules.”

25

And the

Manual goes on, “the statement is intended to advise the public of the general basis and

purpose of the rules.”

26

The APA’s legislative history also includes support for this

understanding. “The required statement of basis and purpose of rules issued,” as both the

House and Senate Judiciary Committee Reports commented on S.7 which became the

APA, “should not only relate to the date so presented but with reasonable fullness explain

the actual basis and objectives of the rule.”

27

20

5 U.S.C. § 553(b) (2012).

21

Id. § 553(c).

22

Id.

23

Id. § 553(b)(3)(A); see Mendelson, supra note 2, at 406 (describing process applicable to guidance

documents).

24

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE, ATTORNEY GENERAL’S MANUAL ON THE ADMINISTRATIVE

PROCEDURE ACT (1947).

25

Id. at 32.

26

Id.

27

H.R. REP. NO. 79-1980, at 259 (1946); S. REP. NO. 79-752, at 201 (1945), as available in ADMINISTRATIVE

PROCEDURE ACT, LEGISLATIVE HISTORY, 79TH CONG., S. Doc. No. 79-248, 1944-46, 225 (1944-46). The

Senate Report also contains as an appendix to the Attorney General’s 1945 report on Senate Bill 7. The

Attorney General’s report stated the following in regards to the statement of basis and purpose:

Section 4 (b), in requiring the publication of a concise general statement

of the basis and purpose of rules made without formal hearing, is not

intended to require an elaborate analysis of rules or of the detailed

considerations upon which they are based but is designed to enable the

public to obtain a general idea of the purpose of, and a statement of the

basic justification for, the rules. The requirement would also serve much

the same function as the whereas clauses which are now customarily

found in the preambles of Executive orders.

9

The idea that the statement of basis and purpose was meant to apprise the public of

the purpose and effect of the rule—that is, that it serve a guidance function—in addition to

disclosing the basis for the rule has sound logic. The statement of basis and purpose is

necessary for the procedural validity of the rule,

28

and constitutes the agency’s

authoritative statement of the rule’s purposes and basis. Because the statement of basis

and purpose is part and parcel of the agency’s rulemaking, it makes sense these documents

would help inform the public about the meaning and application of the rules they

accompany, and that the public and courts would turn to them for those purposes.

29

As this

Report documents, while many agencies rely extensively on statements of basis and

purpose to apprise the public of the application of their rules, the guidance function of

these statements has had not had prominence in policy on guidance nor received much

attention from government bodies or commentators.

30

B. The Expanding Preamble, Ossification, and Separately Issued

Guidance

Part of the explanation for the relative neglect of the guidance function of

preambles is that agencies have come to devote more and more attention in their preambles

to justifying the legal sufficiency of their rules. For some agencies, a clear legal division

of labor has taken hold: The preamble is devoted almost entirely to the legal sufficiency of

the regulation, and guidance is something the agency provides outside the rulemaking, in

separately issued documents.

This development has been conventionally understood as a consequence of

heightened judicial scrutiny review of the rationality of agency regulations that took hold

in the late 1960s and early 1970s in the form of “hard look review” and has persisted ever

since. Hard look review developed as a combination of two doctrinal elements. First, hard

look review adopts the pre-APA administrative law requirement associated with SEC v.

S. REP. NO. 752, at 225 (1945) (also available in ADMINISTRATIVE PROCEDURE ACT, LEGISLATIVE HISTORY,

79TH CONG., 2D SESS., Doc. No. 248, 1944-46, 225 (1946).

28

See Indep. U.S. Tanker Owners Comm. v. Dole, 809 F.2d 847, 852 (1987) (vacating a rule for inadequate

statement of basis and purpose).

29

See Kevin M. Stack, Interpreting Regulations, 111 Mich. L. Rev. 355 (2012) (defending reliance on

agency preambles to interpret regulations).

30

A few more comprehensive commentaries observe that agencies include statements of basis and purpose to

explain their rules, but do not give the practice focused attention. See, e.g., JEFFREY S. LUBBERS, A GUIDE TO

FEDERAL AGENCY RULEMAKING 337 (5th ed., 2012) (“Agencies often use the statement [of basis and

purpose] to advise interested persons how the rule will be applied.”); Richard J. Lazarus, Meeting the

Demands of Integration in the Evolution of Environmental Law: Reforming Environmental Criminal Law,

83 GEO. L.J. 2407, 2437 (1995) (noting that lengthy preambles are just one sources of “underground

environmental law” which also includes extensive guidance).

10

Chenery Corp.

31

(known as Chenery I), which stated that a reviewing court will uphold an

agency’s action based only on “the grounds upon which the agency acted in exercising its

powers.”

32

Second, hard look review embraces a relatively high standard for the quality of

the reasons provided by the agency, despite statements by courts that arbitrary and

capricious review is lenient or narrow.

33

When the Chenery I requirement for a

contemporaneous statement of reasons is combined with a high standard for the quality of

those reasons, the consequences for the agency are clear: For rules to survive judicial

review, the agency must provide an extremely detailed justification of their grounds. The

place for the agency to do so is in the rule’s statement of basis and purpose.

The Supreme Court’s decision in Motor Vehicle Manufacturers Ass’n v. State Farm

Mutual Automobile Insurance Co.

34

still provides the classic statement and illustration of

hard look review. In State Farm, the Court set a high standard for the agency’s level of

express justification in its statement of basis and purpose in the rule. To avoid being

arbitrary or capricious under section 706 of the APA, the agency must “examine the

relevant data and articulate a satisfactory explanation for its action, including a ‘rational

connection between the facts found and the choice made.’”

35

An agency rule would

normally be arbitrary and capricious if “the agency has relied on factors which Congress

has not intended it to consider, entirely failed to consider an important aspect of the

problem, offered an explanation for its decision that runs counter to the evidence before the

agency, or is so implausible that it could not be ascribed to a difference in view or the

product of agency expertise.”

36

In State Farm, the Supreme Court reversed the agency’s

decision to rescind a rule under this standard, in part because the agency provided no

consideration of one of the viable options within the ambit of the existing rule.

37

Since the

State Farm decision, both the Supreme Court and the Courts of Appeals have emphasized

that the vesting of wide power for agencies “carries with it a correlative responsibility for

the agency to explain the rationale and factual basis for its decision,”

38

a duty that agencies

discharge in their statements of basis and purpose. This duty not only includes evaluation

of alternatives and explanation of the basis for the regulations adopted, but also a duty to

discuss salient comments.

39

As a result, the agency’s articulation of the grounds of its

31

318 U.S. 80 (1943).

32

Id. at 95.

33

See, e.g., Citizens to Overton Park, Inc. v. Volpe, 401 U.S. 402, 416 (1971) (describing the standard as a

“narrow” one); Muwekma Ohlone Tribe v. Salazar, 708 F.3d 209, 220 (D.C. Cir. 2013) (same).

34

463 U.S. 29 (1983).

35

Id. at 43.

36

Id.

37

Id. at 51

38

Bowen v. Am. Hosp. Ass’n, 476 U.S. 610, 627 (1986); see also, e.g., Detsel by Detsel v. Sullivan, 895

F.2d 58, 63 (2d Cir. 1990).

39

See, e.g., Am. Mining Cong. v. EPA, 965 F.2d 759, 771 (9th Cir. 1992).

11

action and engagement with commentators in its statement of basis and purpose is

necessary to the validity of the rule.

As these doctrines of judicial review congealed in the contemporary hard look

doctrine, the length of regulatory preambles has grown as measured by the average number

of pages per final rule published in the Federal Register. Based on a study performed by

the Congressional Research Service, the average number of Federal Register pages per

final rule in 1976, 1977, 1978 was 1.7, 2.07, 2.2 respectively, whereas the averages in

2009, 2010, and that 2011 were 5.93, 6.97, and 6.91 respectively.

40

The common sense

explanation is that the prospect of stringent judicial review, which requires the agency to

“show it’s work,” has prompted agencies to devote more energy to writing elaborate

statements of the legal sufficiency of their regulations in their preambles.

41

Other analysis

requirements imposed on agencies also add to the explanatory obligations the agency must

discharge in their preambles, including the analysis requirements imposed by Executive

Order 12,866,

42

the Regulatory Flexibility Act,

43

the Paperwork Reduction Act of 1995,

44

the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969,

45

and the Unfunded Mandates Reform Act

of 1995,

46

among other analysis and consultation requirements.

At the same time that the agency’s duties of explanation—and actual

explanations—of the basis for their rules in preambles has grown, the need for guidance as

to the meaning and application of agency regulations has not gone away.

40

MAEVE P. CAREY, CONG. RES. SERV. R43056, COUNTING REGULATIONS: AN OVERVIEW OF RULEMAKING,

TYPES OF FEDERAL REGULATIONS, AND PAGES IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER, 17-18 (2013) (calculations

produced by dividing the number of pages per final rule by the number of final rules, information reported in

Table 6).

41

See, e.g., Richard J. Pierce, Jr. Seven Ways to Deossify Agency Rulemaking, 47 ADMIN. L. REV. 59, 65

(1997) [hereinafter “Seven Ways”] (suggesting that the stringent judicial gloss on the APA has

“transform[ed] the simple, efficient notice and comment process into an extraordinarily lengthy, complicated,

and expensive process,” discouraging agency use of rulemaking); Thomas O. McGarity, Some Thoughts on

“Deossifying” the Rulemaking Process, 41 DUKE L.J. 1385, 1401 (1992) (attributing the “Herculean effort of

assembling the record and drafting a preamble” to heightened judicial scrutiny of rulemaking); Mark

Seidenfeld, Demystifying Deossification: Rethinking Recent Proposals to Modify Judicial Review of Notice

and Comment Rulemaking, 75 TEX. L. REV. 483, 492-98 (1997) (providing account of ways in which hard

look review has increased burdens of explanation and evidence production on agencies).

42

Exec. Order No. 12,866, 3 C.F.R 638 (1994). For a copy of this Regulatory Planning and Review

Executive Order as amended, see 5 U.S.C. § 601 nts. (2012).

43

5 U.S.C. § 604(a)(2) (2012) (requiring agencies to state changes made in rule in response to comments).

44

44 USC §§ 3501-3521 (2006) (requiring in § 3505 approval by Director of OMB that rules minimize

federal information collection burdens).

45

42 USC § 4321 et seq. (2006) (requiring in § 4332 preparation of environmental impact statement for

significantly effecting the quality of the human environment).

46

2 U.S.C. § 1532(a)(5)(A) (2012) (requiring agencies to respond to comments from state and local

governments).

12

A common suspicion is that the increased costs associated with notice-and-

comment rulemaking has given agencies incentives to look for alternative, less costly ways

to establish policy or advise the public of the agency’s understanding of the law. In

particular, several commentators suggested that the high cost of notice-and-comment

rulemaking has caused agencies to rely to a greater extent on separately issued guidance

documents which need not proceed through notice-and-comment rulemaking,

47

effectively

substituting guidance documents for rulemaking.

48

Recent empirical investigations call

into question this suggestion that agencies rely on guidance documents to avoid the

burdens of notice-and-comment rulemaking. In a study of the Environmental Protection

Agency (EPA), Food and Drug Administration (FDA), Federal Communications

Commission (FCC), Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OHSA), and the

Internal Revenue Service (IRS), between 1996 and 2006, Connor Raso found that agencies

do not increase their issuance of guidance strategically,

49

and that the body of significant

legislative rules issued still dwarfs that of significant guidance.

50

In an extensive study of

the Department of the Interior, Jason and Susan Webb Yackee also found no support for

increased reliance on nonlegislative rules between 1950-1990.

51

More generally, Anne

Joseph O’Connell also found that the volume of agency notice-and-comment rulemaking

remains significant, and thus does not appear to be so costly that it is no longer a viable

option for agencies.

52

47

See 5 U.S.C. § 553(b) (2012) (excepting interpretative rules and general statements of policy from notice

and comment requirements).

48

See, e.g., Robert A. Anthony, Interpretive Rules, Policy Statements, Guidances, Manuals, and the Like—

Should Federal Agencies Use Them to Bind the Public?, 41 DUKE L.J. 1311, 1316-17(1992) (arguing that

with the increased cost of notice-and-comment rulemaking, agencies are increasingly willing to rely on forms

of nonlegislative rules, such as interpretative rules and general statements of policy to implement their

statutes); Pierce, Seven Ways, supra note 41, at 86 (same).

49

Connor Raso did not find evidence that agencies issued guidance documents more often as presidential

terms waned, nor more frequently during periods of divided government. See Connor N. Raso, Note,

Strategic or Sincere? Analyzing Agency Use of Guidance Documents, 119 YALE L.J. 782, 806-07 (2010).

50

See Raso, supra note 49, at 813-14 (Table 3 showing that the ratio of significant guidance documents to

significant legislative rules ranges from .00 and .01 (Defense and Energy) to .31 and .35 (Education and

Homeland Security)).

51

Jason Webb Yackee & Susan Webb Yackee, Testing the Ossification Thesis: An Empirical Examination of

Federal Regulatory Volume and Speed, 1950-1990, 80 GEO. WASH. L. REV. 1414, 1461 (2012). The

Yackees’ article includes interim final rules and guidance documents in a category on “no-comment

regulations,” drawn from searches of the Federal Register. With regard to guidance published in the Federal

Register, this methodological choice means that their findings of no increased reliance on guidance is very

conservative because they are counting interim final rules in this category. However, their study does not

capture guidance that is not published in the Federal Register, so may also understate agency reliance on it.

52

See Anne Joseph O’Connell, Political Cycles of Rulemaking: An Empirical Portrait of the Modern

Administrative State, 94 VA. L. REV. 889, 936 (2008) (suggesting that volume of agency rulemaking shows it

is not ossified). Interestingly, Anne Joseph O’Connell’s study reveals that agencies have increased issuance

of direct final rules and interim final rules. See id. Both direct final rules and interim final rules include

statements equivalent to statements of basis and purpose, but they do not undergo a pre-publication comment

period. NAT’L ARCHIVES & RECORDS ADMIN., FEDERAL REGISTER DRAFTING DOCUMENT HANDBOOK, 2-6

to 2-8 (1998) (noting that direct final rules and interim final rules should include preambles explaining the

13

These studies complicate and may undermine the view that agencies have

increasingly relied on separately issued guidance documents in response to the greater

demands on, and costs of, notice-and-comment rulemaking. But these studies do not

address the extent to which the agency preambles have been devoted to justifying the legal

sufficiency of the regulations as opposed to serving a guidance function. The increased

legal demands saddled upon the agency’s preamble have all been directed toward legal

sufficiency or analysis requirements, not their guidance function.

53

To the extent those

increased justificatory and analysis requirements have had an effect on agency’s activities

in rulemaking—and the lengthening of agency preambles is a good indication that they

have an effect—they have augmented the prominence of the justificatory role of the

preamble. At the same time, even as policymakers and commentators have devoted more

attention to agencies’ use of guidance, that attention has been almost exclusively directed

to separately issued guidance documents, not guidance provided within rulemaking

documents. We need a better understanding of the guidance function these documents

do—and must—serve.

III. The Law Governing Contemporaneous Guidance

Assessment of best practices for providing guidance in rulemakings—that is, best

practice for contemporaneous guidance—requires understanding the legal regime and

constraints that apply to providing guidance in regulatory preambles, the regulatory text

(including any appendices), or in separately issued documents. Despite the ubiquity of

contemporaneous guidance,

54

there are few, if any, resources that draw together the legal

regime applicable to contemporaneous guidance. From the perspective of the agency and

the public, there are a host of questions about how the general law of guidance applies to

contemporaneous guidance, including:

What, if any, process requirements apply to issuing contemporaneous

guidance?

What, if any, process requirements apply to revising contemporaneous

guidance?

rule’s purpose and grounds). Agencies’ increased reliance on these forms suggests that at least the “notice-

and-comment rulemaking has significant costs that the agencies want to avoid.” Joseph O’Connell, supra, at

936.

53

See, e.g., Unfunded Mandates Reform Act, 2 U.S.C. § 1523(a) (2006); Small Business Regulatory

Enforcement Fairness Act, 5 U.S.C. § 609, Pub. L. No. 104-121, 110 Stat. 857 (1996); Regulatory Flexibility

Act, 44 U.S.C. §§ 301-612 (2006); Congressional Review Act, 5 U.S.C §§ 801-08 (2006); Paperwork

Reduction Act, 44 U.S.C. §§ 3501-20 (2006); 44 U.S.C. § 3504(c) (2006).

54

See infra Part IV.

14

When is contemporaneous guidance subject to OIRA review?

What, if any, guidance must be included in a regulatory preamble or

regulatory text, or separately issued document?

What, if any, guidance may not be included in a regulatory preamble or

regulatory text?

What forms of contemporaneous guidance are reviewable?

What standards of judicial review apply?

This Part addresses these questions, and then provides a summary of the answers in

Table 1.

55

A. Process Requirements for Issuing Contemporaneous Guidance

One of the distinctive features of separately issued guidance documents is that they

are exempt from the requirements of notice-and-comment under APA § 553(b)(A).

56

But

this does not mean that there are no applicable procedural requirements. The APA requires

that interpretive rules and general statements of policy be published in the Federal

Register,

57

and that other forms of guidance be publically available.

58

Preambles and

regulatory text obviously must meet that publication requirement.

The more involved and less explored process issue for contemporaneous guidance

arises from those agencies covered by OMB’s Good Guidance Bulletin.

59

As noted at the

outset, this Bulletin defines “guidance documents” to exclude regulatory actions,

60

so it

would not apply to any guidance the agency provided in the text of its regulations. But

under the definition in the Bulletin, agency preambles (as well as separately issued

documents) could qualify as guidance documents within the Bulletin because they may be

statements of “general applicability and future effect . . . that set[] forth a policy on a . . .

regulatory issue or interpretation of a . . . regulatory issue.”

61

Likewise, statements in an

agency preamble could also constitute “significant guidance” which includes guidance

leading to an annual effect on the economy of more than $100 million, creating serious

55

See infra Section III(H).

56

5 U.S.C. § 553(b)(A) (2012).

57

See id. § 552(a)(1)(D).

58

See id. § 552(a)(2)(B) (2012).

59

OMB’s Good Guidance Bulletin, supra note 1. The Bulletin applies only to executive agencies. See id. §

I.2 (defining “agency” as agencies other than those considered to be independent regulatory agencies under

44 U.S.C. § 3205(5)).

60

Id. § I.3 (“The term ‘guidance document’ means an agency statement of general applicability and future

effect, other than a regulatory action (as defined in Executive Order 12866, as further amended by, section

3(g)), that sets forth a policy on statutory, regulatory, or technical issue or an interpretation of a statutory or

regulatory issue.”).

61

Id.

15

inconsistencies with another agency’s actions or planned actions, altering budget impacts

on entitlements, or raising novel legal issues arising out of legal requirements or the

president’s priorities or Executive Order 12,866.

62

Accordingly, for executive agencies, to the extent any statements in an agency

preamble as well as those in separately issued documents would be considered “significant

guidance documents” or even “economically significant guidance documents” under the

Bulletin, the agency would have to comply with the procedural requirements the Bulletin

imposes.

63

Most interesting for their application to preambles are the requirement that: (1)

there be a designation of the statement as “guidance” (or its equivalent),

64

(2) the agency

maintain on its web site a list of significant guidance documents,

65

and (3) the agency

structure a means for the public to submit comments on significant guidance documents.

66

While many agencies provide extensive guidance about the meaning and operation of their

regulations in their preambles, few agencies appear to treat their preambles as subject to

the procedural requirements of OMB’s Good Guidance Bulletin which, by its own terms,

could apply to guidance provided in preambles.

Consider in particular OMB’s Good Guidance Bulletin’s requirement that each

agency maintain on its web site a list of its current significant guidance documents in

effect, including a link to the document.

67

Based on a review of the web sites of the 21

executive branch agencies that have issued an economically significant regulation in the

last 15 years,

68

only the Department of Transportation’s web site on guidance mentions

preambles as a source of guidance.

69

In sum, while guidance provided in agency preambles or in regulatory text clearly

meet the APA’s publication requirements, these same statements, if their effects are

significant, could require compliance with OMB’s Good Guidance Bulletin. That would

require the agency to be conscientious about how it designated those guidance portions, to

62

Id. § I.4(a)(i)-(iv).

63

Id. § II.2-3 (outlining basis procedures for significant guidance). The Bulletin’s imposition of procedural

requirements for issuing guidance builds upon ACUS Recommendation 92-2 on Agency Policy Statements.

That recommendation urged agencies to provide procedures to challenge the legality and wisdom of the

statements prior to these policies being applied. See Admin. Conf. of the United States, Agency Policy

Statements, Recommendation 92-2, ¶ II(B), 57 Fed. Reg. 30,103 (June 18, 1992).

64

Id. § II.2 (setting out requirement elements for significant guidance).

65

Id. § III.1 (providing for Web posting of significant guidance).

66

Id. § III.2 (setting forth requirements for public to submit comments and complaints about its guidance).

67

Id. § III.1.

68

This list of agencies is drawn from LEWIS & SELIN, supra note 17, at 132 (Table 20). It includes: USDA,

DOC, DOD, DOED, HHS, DHS, HUD, DOI, DOJ, DOL, STAT, DOT, DTRS, DVA, EPA, EEOC, OMB,

OPM, RRB, SBA, and SSA.

69

The web sites on guidance for the agencies noted did not include mention of preambles or a rule’s

statement of basis and purpose, except for DOT (websites on guidance visited March 2014).

16

post or mention preambles alongside other significant guidance on their web sites, and

even to provide an opportunity to comment on the significant guidance in preambles,

among other requirements.

B. Process Requirements for Revising Contemporaneous Guidance: The

Impact of Alaska Professional Hunters

The process requirements that apply to an agency decision to revise

contemporaneously issued guidance are even clearer than those that apply to issuing

contemporaneous guidance. Clearly guidance issued as part of a regulatory text can only

be revised through a new notice-and-comment proceeding. Based on the rule adopted by

the D.C. Circuit in Alaska Prof’l Hunters Ass’n v. FAA

70

and Paralyzed Veterans of

America v. D.C. Arena,

71

in some cases, agencies must also proceed through notice-and-

comment to revise guidance provided in their preambles.

The “Alaska Hunters” rule, also known as the “one-bite” rule,

72

states that “[w]hen

an agency has given its regulation a definitive interpretation, and later significantly revises

that interpretation, the agency has in effect amended its rule, something it may not

accomplish without notice and comment.”

73

As the D.C. Circuit recently clarified in

Mortgage Bankers Ass’n v. Harris,

74

this rule involves two basic inquiries: whether the

interpretation is definitive (“definitiveness”), and whether there has been a significant

change in the interpretation (“significant change”), but does not require substantial and

justified reliance on the prior interpretation.

75

In Paralyzed Veterans, the D.C. Circuit characterized a change in an interpretation

of a rule as an “amendment” to a regulation.

76

The court then turned to APA § 551(5),

which defines “rulemaking” as including “formulating, amending, or repealing a rule.”

77

On this basis, the court concluded that amendments in the form of changes to

interpretations must go through notice-and-comment.

78

As commentators have pointed out,

the Paralyzed Veterans court neglected to consider that § 553, which sets forth the

70

177 F.3d 1030, 1035-36 (D.C. Cir. 1999).

71

117 F.3d 579, 588 (D.C. Cir. 1997).

72

Stack, supra note 29, at 415–16.

73

177 F.3d at 1034.

74

720 F.3d 966 (D.C. Cir. 2013), petition for cert. filed, Nos. 13-1041, 13A636 (Feb 28, 2014).

75

Id. at 969; Matthew P. Downer, Note, Tentative Interpretations: The Abracadabra of Administrative

Rulemaking and the End of Alaska Hunters, 67 VAND. L. REV. (forthcoming 2014) (exploring distinction

between definitive and tentative interpretations).

76

See Paralyzed Veterans, 117 F.3d at 586.

77

Id.

78

Id.; 5 U.S.C. 551(5) (2012).

17

requirements for notice-and-comment rulemaking, specifically exempts “interpretative

rules” from notice-and-comment.

79

Alaska Hunters formalized Paralyzed Veterans into a doctrine.

80

At issue in Alaska

Hunters was a thirty-year-old practice of the Federal Aviation Administration’s Alaska

regional office that uniformly advised hunting and fishing guides flying clients on Alaskan

hunting tours that they were not considered “commercial operators,” a treatment that

resulted in exempting these businesses from some FAA regulations.

81

In 1997, FAA

officials in Washington, D.C. published a “Notice to Operators” announcing that it would

interpret these hunting businesses as “commercial operators” subject to commercial

operator regulations going forward.

82

Relying on Paralyzed Veterans, the Alaska Hunters

court held that the “Notice to Operators” was procedurally invalid because it effectively

amended a regulation by changing a definitive interpretation without notice-and-

comment.

83

The prior interpretation, the court noted, had become “an authoritative

departmental interpretation, an administrative common law.”

84

In subsequent decisions,

the D.C. Circuit has narrowed the scope of this rule somewhat, holding that when an

administrative interpretation includes conditional language (e.g., “may use,” “can be

used”) or did not establish an “express, direct, and uniform interpretation,”

85

it is not

definitive. While roundly criticized by commentators as inconsistent with the APA §

553,

86

the D.C. Circuit and several other Circuits continue to apply this doctrine.

87

79

Jon Connolly, Note, Alaska Hunters and the D.C. Circuit: A Defense of Flexible Interpretive Rulemaking,

101 COLUM. L. REV. 155, 160, 165 (2001).

80

Alaska Prof’l Hunters Ass’n, 177 F.3d at 1034 (citing Paralyzed Veterans, 117 F.3d at 586) (“‘Rule

making,’ as defined in the APA, includes not only the agency’s process of formulating a rule, but also the

agency’s process of modifying a rule.”).

81

Id. at 1031-32.

82

Id. at 1033.

83

Id. at 1034.

84

Id. at 1035.

85

MetWest Inc. v. Sec’y of Labor, 560 F.3d 506, 509 (D.C. Cir. 2009) (conditional statement,

“circumstances may exist,” in guidance does not establish a definitive agency interpretation); Darrell

Andrews Trucking, Inc. v. Fed. Motor Carrier Safety Admin., 296 F.3d 1120, 1126 (D.C. Cir. 2002)

(presence of language “can be used” or “could be used” rendered guidance ambiguous and thus did mark a

definitive interpretation); Ass’n of Am. R.R.s v. Dep’t of Transp., 198 F.3d 944, 949 (D.C. Cir. 1999)

(agency interpretations not sufficiently authoritative or uniform).

86

Richard W. Murphy, Hunters for Administrative Common Law, 58 ADMIN. L. REV. 917, 918 (2006)

(“Academic commentary on [the Alaska Hunters doctrine] has been scathing.”); see also William Funk, A

Primer on Nonlegislative Rules, 53 ADMIN. L. REV. 1321, 1329 (2001) (criticizing the D.C. Circuit's

reasoning in Alaska Hunters); Pierce, Seven Ways, supra note 41, at 566 (same); Peter L. Strauss, Publication

Rules in the Rulemaking Spectrum: Assuring Proper Respect for an Essential Element, 53 ADMIN. L. REV.

803, 846 (2001) (same); Connolly, supra note 79, at 157 (same).

87

See Mortg. Bankers Ass’n v. Harris, 720 F.3d 966 (D.C. Cir. 2013) (reaffirming the Alaska Hunters

doctrine). The Third, Fifth and Sixth Circuits have adopted the Alaska Hunters doctrine. See SBC Inc. v.

FCC, 414 F.3d 486, 498 (3d Cir. 2005); Dismas Charities, Inc. v. U.S. Dept. of Justice, 401 F.3d 666, 682

(6th Cir. 2005); Shell Offshore Inc. v. Babbitt, 238 F.3d 622, 629 (5th Cir. 2001). In contrast, the First,

Seventh, and Ninth Circuits have rejected the Alaska Hunters doctrine. See Abraham Lincoln Mem’l Hosp. v.

18

The Alaska Hunters rule has clear implications for preambles. It seems clear that

guidance provided in a preamble to a regulation could be definitive under Alaska Hunters.

Guidance provided in a preamble is clearly authoritative; it is the agency as an institution

that issues it. So long as it was not conditional or ambiguous, it would qualify as a

definitive interpretation. As a result, under Alaska Hunters, for the agency to significantly

change its definitive guidance provided in a preamble would require the agency to undergo

a new notice-and-comment proceeding.

The idea that a notice-and-comment proceeding is required to change guidance

given in a preamble to a regulation may strike many as an odd result in part because it

appears to blur the distinction between rule and preamble. That blurring follows from

Alaska Hunters, but also has an important implication for agencies: For definitive

guidance, there may be less procedural difference that would initially appear between

statements in the preamble and in the regulatory text. So long as the statements in the

preamble are definitive, then they can be changed, like regulatory text, only through

notice-and-comment. So the difference in procedural requirements is only a difference in

the processes that govern their issuance: Regulatory text is subject to notice-and-comment

under the APA, whereas guidance in a preamble, like separately issued guidance, is at most

subject to the notice obligations imposed by OMB’s Good Guidance Bulletin (which in

turn involves notice and comment for economically significant guidance).

C. When Is Contemporaneous Guidance Subject to OIRA Review?

For agencies that are not independent regulatory agencies,

88

preambles to

significant final rules, the text of those rules, as well as significant guidance documents are

all subject to some oversight by the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs under

Executive Order 12,866.

89

Executive Order 12,866 defines regulatory actions as “any substantive action by an

agency (normally published in the Federal Register) that promulgates or is expected to

lead to the promulgation of a final rule or regulation . . . advanced notices of proposed

rulemaking, and notices of proposed rulemaking.”

90

Preambles to final rules and

Sebelius, 698 F.3d 536 (7th Cir. 2012); Erringer v. Thompson, 371 F.3d 625 (9th Cir. 2004); Warder v.

Shalala, 149 F.3d 73 (1st Cir. 1998). The Tenth Circuit appeared to criticize the Alaska Hunters decision, but

did not either formally adopt or reject it. See United States v. Magnesium Corp. of Am., 616 F.3d 1129 (10th

Cir. 2010).

88

Exec. Order. No. 12,866 § 3(b), 3 C.F.R 638 (1994) (defining agencies, unless otherwise noted, as

excluding independent regulatory agencies as listed in 44 U.S.C. § 3502(10)).

89

Id. at § 3(e).

90

Id.

19

regulatory text are clearly “regulatory actions.” As such, under the Executive Order’s

Centralized Review provisions, for regulations that are “significant,”

91

covered agencies

must provide the text of the preamble and the regulatory text to OIRA for review.

92

In addition, “significant” guidance documents are also subject to OIRA review.

While President Obama revoked President Bush’s Executive Order which formally

subjected guidance documents to review,

93

that did not remove significant guidance

documents from OIRA review. As former OIRA Administrator Cass Sunstein reports,

“Across multiple administrations, OIRA has long reviewed such [guidance] documents . . .

so long as they count as ‘significant.’”

94

This understanding was confirmed by then-OMB

Director Peter Orzag in a March 2009 memorandum that made clear that the revocation of

President Bush’s Executive Order formally including guidance in regulatory review

restored regulatory review to the process between 1993 and 2007.

95

“During that period,”

Director Orzag wrote, “OIRA reviewed all significant proposed final agency actions,

including significant policy and guidance documents.”

96

D. What Contemporaneous Guidance is Required?

While the law does not require including particular guidance in regulatory text,

97

there are minimum obligations for contemporaneous guidance to be included in regulatory

preambles as well as in separate guidance documents called “compliance guides” for rules

that have “a significant impact on a substantial number of small entities,” as required by

the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act of 1996 (SBREFA).

98

91

Id. § 3(e).

92

Id. § 6(a)(3)(B).

93

Exec. Order No. 13,497, 3 C.F.R. § 218 (2010), revoking Exec. Order No. 13422, 3 C.F.R. § 191 (2008)

(revoked) (subjecting guidance to regulatory review).

94

Cass R. Sunstein, The Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs: Myths and Realities, 126 HARV. L.

REV. 1838, 1853 (2013).

95

See Orzag Memorandum, supra note 2. The issuance of this memorandum, Sunstein reports, “reflects

broad support for such review within the Executive Office of the President,” notwithstanding the fact that

guidance might strictly fit within Executive Order 12,866’s definition of “regulatory action.” See Sunstein,

supra note 94, at 1853 n.60. For a description of the character of OIRA’s review of guidance documents

during that period, see Jennifer Nou, Agency Self-Insulation Under Presidential Review, 126 HARV. L. REV.

1755, 1785 (2013).

96

See Orzag Memorandum, supra note 2.

97

President Clinton’s directive on plain language, which includes plain language in final rules, remains in

effect. See Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies on “Plain Language in

Government Writing” (June 1, 1998), 63 Fed. Reg. 31,885 (June 10, 1998).

98

5 U.S.C. § 601 notes, § 212 (requiring the production of compliance guides whenever the agency must

produce a regulatory flexibility analysis under 5 U.S.C. § 605(b) and quoting § 605(b)).

20

1. Preambles

The near exclusive focus on the justificatory function of statements of basis and

purpose in regulatory preambles also completely occludes the question of what minimum

level of guidance preambles must provide. There are two legal sources that could be

understood to impose a minimum guidance obligation on the agency: the requirement of

APA § 553 that the agency issue a “statement of [] basis and purpose,” and the Regulatory

Flexibility Act’s requirement that agencies engaged in rulemaking under § 553 provide a

“statement of the need for, and objective of, the rule.”

99

These requirements ensure that a minimum guidance function is served by the

preamble. Independent U.S. Tanker Owners Committee v. Dole

100

provides the established

formulation of the necessary requirements for an agency’s statement of basis and purpose

to be procedurally valid. While the statement need not “be an exhaustive, detailed account

of every aspect of the rulemaking proceedings,” the statement “should indicate the major

issues of policy that were raised in the proceedings and explain why the agency decided to

respond as it did, particularly in light of the statutory objectives that the rule must

serve.”

101

Under this standard, the Independent U.S. Tankers court concluded that the

agency’s statement did not explain how the rule furthered statutory objectives, and

accordingly vacated the rule.

102

Requiring this articulation in the statement of basis and purpose clearly helps a

reviewing court assess whether the agency has taken a hard look at the problem in light of

its statutory objectives. But it just as clearly serves a guidance function. It requires the

agency to provide an independent articulation of the purpose of the rule and its place in the

implementation of the statute. The fact, as Independent Tankers held, that issuing a

statement of basis and purpose with an adequate explanation of how the rule furthers the

statute’s purposes is procedurally necessary for a notice-and-comment rulemaking

103

suggests that guidance is one of the purposes—and minimum obligations imposed on—

these statements. In other words, part of what makes a statement of basis procedurally

valid is providing a minimum level of guidance that explains how the rule implements the

statute’s purpose. From this perspective, statement of basis and purpose that falls short of

this minimum requirement does not perform its necessary guidance function of stating the

rule’s purposes in light of statutory objectives.

104

99

5 U.S.C. § 604(a)(1) (2012)

100

809 F.2d 847 (D.C. Cir. 1987).

101

Id. at 852.

102

Id.

103

Id.

104

Direct Final Rules and Interim Final rules should also include the functional equivalent of a preamble, see

FEDERAL REGISTER DRAFTING DOCUMENT HANDBOOK, supra note 52, at 2-6 to 2-8 (1998) (noting that direct

21

The Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA) requires that when an agency promulgates a

final rule through notice-and-comment, the agency must provide a “regulatory flexibility

analysis” that includes “a statement of the need for, and objectives of, the rule,”

105

published in the Federal Register.

106

The RFA’s requirements are “[p]urely procedural”

and so “requires nothing more than that the agency file a [final regulatory flexibility

analysis] demonstrating a ‘reasonable, good-faith effort to carry out [RFA’s] mandate’.”

107

Still, RFA sets out “precise, specific steps the agency must take.”

108

And reviewing courts

will assess whether the agency’s analysis “addressed all of the legally mandated subject

areas.”

109

Substantial compliance is not authorized.

110

Accordingly, where an agency fails

to address one of those mandated subjects, a reviewing court will remand to the agency to

conduct the analysis required by RFA.

111

While courts deferentially review the substance of an agency’s final regulatory

flexibility analysis for the purposes of assessing compliance with RFA, the fact remains

that the agency must state the need for and objectives of the rule. That requirement also

enforces discipline on the agency, requiring it to have a clearly stated objective and

rationale for its rules. The requirement of publication in the Federal Register suggests that

there is a minimum guidance function enforced by RFA as well.

At a minimum, both the APA and the RFA require the agency to provide a

statement of the need for the rule and the rule’s objectives in light of the authorizing

statute’s aims. Preambles that do not include those statements do not satisfy their guidance

function and thus should be procedurally invalid.

2. Separately Issued Documents

Section 212 of SBREFA requires agencies to publish a “small entity compliance

guide” at the same time as the publication of the final rule (or as soon as possible

final rules and interim final rules should include preambles explaining the rule’s purpose and grounds);

Ronald M. Levin, Direct Final Rulemaking, 64 GEO. WASH. L. REV. 1, 16-18 (1995) (noting direct final rules

and interim final rules include functional equivalent of statement of basis and purpose), which could also be

viewed as having the same minimum guidance function.

105

5 U.S.C. § 604 (2012).

106

5 U.S.C. § 604(a)(6)(b) (2012).

107

United States Cellular Corp. v. FCC, 254 F.3d 78, 88 (D.C. Cir. 2001).

108

Nat’l Tel. Co-op. Ass’n v. FCC, 563 F.3d 536, 539-40 (D.C. Cir. 2009).

109

Id.

110

Aeronautical Repair Station Ass’n v. FAA, 494 F.3d 161, 178 (D.C. Cir. 2007) (remanding to FAA

inadequate FRFA but not staying effect of rule).

111

See id. at 177-78.

22

thereafter) and no later than when the rule becomes effective.

112

These guides shall

“explain the actions a small entity is required to take to comply with a rule,”

113

which

“shall include a description of actions needed to meet the requirements of a rule, to enable

a small entity to know when such requirements are met,”

114

and include descriptions of

procedures that “may assist a small entity in meeting” the rule’s requirements.

115

These

guides must be written “using sufficiently plain language likely to be understood by the

affected small entities.”

116

These compliance guides must be easily accessible on the web

site of the agency, and distributed to known industry contacts, such as affected

associations.

117

E. What May Not Be Included in Contemporaneous Guidance?

1. Restrictions on Guidance in the Code of Federal Regulations

Only those rules that have “general applicability and legal effect” may be codified

in the regulatory text of the Code of Federal Regulations.

118

The regulations implementing

this statutory requirement define documents have “general applicability and legal effect” to

mean “any document issued under proper authority prescribing a penalty or course of

conduct, conferring a right, privilege, authority, or immunity, or imposing an

obligation.”

119

Thus, the codified text of the CFR may not include guidance, though

agencies may include notes and examples with their codified text, or guidance in

appendices to codified text.

120

2. Preamble-Specific Restrictions

a. Restriction on Preemption Statements. Perhaps the most straightforward

and recent restriction on the guidance statements that may be made in preambles is

President Obama’s Memorandum for the Heads of Executive Departments and Agencies

112

Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act, Pub. L. No. 104-121, § 212(a), 110 Stat. 873,

codified at 5 U.S.C. § 601 nt. (2012).

113

Id. § 212(a)(4).

114

Id. § 212(a)(4)(B)(i).

115

Id. § 212(a)(4)(B)(ii).

116

Id. § 212(a)(5). The Plain Writing Act of 2010, Pub. L. No. 111, 124 Stat. 2861, codified at 5 U.S.C. §

301 nt. (Supp. V 2011), also imposes a plain writing requirement on documents that “explain[] to the public

how to comply with a requirement the Federal Government administers or enforces.” Id. § 3.

117

Id. § 212(a)(2).

118

44 U.S.C. § 1510(a) (2006); 1 C.F.R. § 8.1 (2013) (the Code of Federal Regulations shall contain each

Federal regulation of general applicability and legal effect); see also Wilderness Soc. v. Norton, 434 F.2d

584, 596 (D.C. Cir. 2006) (the CFR may contain only documents having general applicability and legal

effect).

119

1 C.F.R. § 1.1 (2013).

120

FEDERAL REGISTER DRAFTING DOCUMENT HANDBOOK, supra note 52, at 7-9 (discussing use of

appendices to clarify but not to impose substantive obligations).

23

on Preemption.

121

This Memorandum directs executive agencies not to include statements

in regulatory preambles to the effect that the agency intends the regulation to preempt state

law unless preemption provisions are also codified in the regulation’s text.