Crossing Boundaries

for Learning

– through Technology

and Human Eorts

Crossing Boundaries

for Learning

– through Technology

and Human Eorts

Hannele Niemi, Jari Multisilta

& Erika Löfström (Eds.)

CICERO Learning Network, University of Helsinki

CICERO Learning

PO Box 9

(Siltavuorenpenger 5 A)

00014 University of Helsinki

FINLAND

Email: cicero@cicero.

Facebook: facebook.com/cicerolearning

Phone: +358 9 191 20642

Fax: +358 9 191 20616

© CICERO Learning Network, University of Helsinki

Layout:

PS-kustannus/Marja Junnila ja Janne Hiltunen

Press:

Hansaprint 2014

ISBN 978-952-10-9878-9 (nid.)

ISBN 978-952-10-9879-6 (PDF)

5

Preface

Preface

TEPE is an academic network that promotes research- and evidence-based

teacher education. e annual conference brings together educational re

-

searchers, policy makers, teachers and practitioners from Europe and beyond.

is book is based on selected papers presented in the annual conference

of the Teacher Education Policy in Europe (TEPE) network in 2014 at the

University of Helsinki. e title of the conference was Learning Spaces with

Technology for 21st Century Skills in Teaching and Teacher Education.

TEPE conferences also provide a space for more general themes of teaching

and teacher education, in addition to the specic topic of the annual con

-

ference. In addition to technology-related themes, in this edition, there are

also articles that describe human eorts to provide learning spaces for all.

All papers are blindly peer-reviewed. e editors wish to thank all the

reviewers for their important work. ey have given extremely valuable com

-

ments and advice to the authors. e TEPE Board and local conference organ-

izers would also like thank CICERO Learning Coordination for managing

the review process. We wish to thank the University of Helsinki for providing

support and space for the conference and to thank the Federation of Finn

-

ish Learned Societies for its nancial support. We are also deeply thankful to

Tekes, the national agency for technology and innovations in Finland, which

has launched the Learning Solutions Programme and accepted the Finnable

2020 project as part of it. e TEPE conference was integrated into the project

work of Finnable 2020 and also created an important platform for discussions

regarding how to use technology as a tool for learning.

In Helsinki, March 20, 2014

Hannele Niemi

PH.D., Professor of

Education, University

of Helsinki

Jari Multisilta, PH.D.,

Professor, Dr. Tech.,

Director, Cicero Learn

-

ing,University of Hel-

sinki

Erika Löfström

PH.D., Senior

Researcher

University of Helsinki

Table of Contents

Prologue: Crossing Boundaries for Learning ................................................................9

Hannele Niemi, Jari Multisilta and Erika Löfström

Part I: Crossing Boundaries through Technology

1. Toward Global Sharing Pedagogy .......................................................................... 17

Hannele Niemi and Jari Multisilta

2. Crossing School-Family Boundaries through the Use of Technology ......... 37

Tiina Korhonen and Jari Lavonen

3. Crossing Classroom Boundaries through the Use of

Collaboration-Supporting ICT: A Case Study on School -

Kindergarten - Library - Senior Home Partnership ........................................... 67

Minna Kukkonen and Jari Lavonen

4. Crossing Classroom Boundaries in Science Teaching and

Learning through the Use of Smartphones ........................................................ 91

Kati Sormunen, Jari Lavonen and Kalle Juuti

Part II: New Tools for Teaching and Learning

5. Teachers’ Capacity to Change and the ICT Environment:

Insights from the ATEPIE Project .........................................................................113

JelenaRadišićandJasminkaMarković

6. Prospective Teachers and New Technologies:

A Study among Student Teachers ....................................................................... 135

Anne Huhtala

7. E-Portfolio as a tool for Guiding Higher Education

Students’ Growth to Entrepreneurship .............................................................. 155

Tarja Römer-Paakkanen, Auli Pekkala and Päivi Rajaorko

8. Aordance as a Key Aspect in the Creation of New learning .......................191

Susanne Dau

Part III: Getting along with Dierent Learners

9. Conicting Ideas on Democracy and Values

Education in Swedish Teacher Education .......................................................... 223

Björn Åstrand

10. Demands and Challenges:

Experiences of Ethiopian Rural School Teachers.............................................253

Kati Keski-Mäenpää

Author biographies ......................................................................................................... 277

9

Prologue: Crossing Boundaries for Learning

Prologue: Crossing

Boundaries for Learning

Hannele Niemi, Jari Multisilta and Erika Löfström

e theme of the 2013 TEPE Conference was Learning Spaces with

Technology for 21st Century Skills in Teaching and Teacher education.

e motive behind the conference was that 21

st

century skills have become

an urgent priority of educational systems all over the world. Changing

environments, e.g., developing technological infrastructures, increasingly

networked communities, and constant access to digital resources, have

made 21

st

century skills more important than ever. ere are several deni-

tions (e.g. Ananiadou, & Claro, 2009; Binkley et al., 2012; Grin, Care,

& McGaw, 2012) of “21

st

century skills,” but all share common features.

Learners require active inquiry skills, knowledge must be constructed and

assessed, and learning environments are changing in a way that we cannot

even forecast. In most cases, knowledge is created in groups, and learners

learn from one another. Many prior boundaries between formal and non-

formal learning sites are in the process of breaking down. Learning spaces

are becoming more overlapping, seamless, joined, and blended. Learning

continues throughout life, and a school’s task is to provide learners with

the skills and competences with which they can continue their learning in

dierent phases of their lives. Learners also require competences in terms

of how to use learning environments that are nearly boundless and create

knowledge that will become endlessly growing and up-dated. We know

that innovations grow from collaboration and networking. e major

message of the various denitions of “21

st

century skills” is that learners

need new ways to think, learn and work. ey must self-regulate their

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Human Eorts

10

own learning. ey need collaborative skills and active knowledge creation

competences. To support these skills and competences, both students and

teachers are learners. Teacher education has a critical role in how these

skills can be achieved.

It is not only the need for 21

st

skills but also emerging technologies that

pose new challenges to schools and teachers. e younger generation is

using technology outside school in its free time, but in many schools, the

adoption of technologies is lagging. Technologies should be seen as tools

to improve and mediate learning and the learning process. Digital literacy

is one of the key competences needed for the future, and it is often listed

among the 21

st

century skills. However, technologies can also support

collaborative learning and knowledge creation, so technologies have a

role as a tool for use with other 21

st

century skills as well. e adoption

of new technologies for classroom use is not an easy task. is is why we

need case descriptions of the best practices and the results from scientic

research to help teachers develop their teaching methods and meet the

challenges they face.

e Organizing Committee of the TEPE Network Conference 2013

invited papers that addressed the use of new technologies and the promo

-

tion of 21

st

century skills. e main themes of the call were as follows: New

technologies in teaching, learning, and teacher education; Teachers’ and

students’ 21

st

century skills; Promoting these skills in teacher education;

and 21st century skills in educational policy. e TEPE annual meeting

has always had also an option, in addition to the main conference theme,

to provide space for presentations about more general, urgent themes of

teaching and teacher education. As editors of this book, we realize how

important it is to widen the scope to include a discussion of the need to

provide learning spaces for all. Not all learning environments are techno

-

logical, but students must still learn skills that will help them to face the

future. Technology can be an important tool, but without other education

-

ally supportive structures and equal opportunities for a good education,

technology alone cannot solve problems or provide the necessary skills for

the future. With these reections, the editors titled the book as follows:

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Hu

-

man Eorts.

11

Prologue: Crossing Boundaries for Learning

In the introductory chapter, Hannele Niemi and Jari Multisilta intro-

duce a framework for Global Sharing Pedagogy (GSP). e model takes

as its point of departure the skills and competences required in working

life and, more generally, in life-long learning. Many of the subsequent

papers can be viewed in light of the mediating activities elemental to GSP,

namely digital literacy, collaboration, networking, and knowledge and

skills creation. ese are the key activities in learning engagement, and ICT

tools can be harnessed in many ways to support the development of these

competencies. e authors provide an example from digital storytelling.

e papers in the rst section explore how technology creates new

practices in schools. Technology has been used to facilitate personalized

learning and inclusion in science education, as well as in partnerships be

-

tween schools, homes, and the wider community. In their paper “Crossing

classroom boundaries in science teaching and learning through the use

of smartphones,” Kati Sormunen, Jari Lavonen,

and Kalle Juuti describe

how everyday technology might be incorporated into science teaching in

order to personalize the learning experience and engage pupils with science

content. e authors identify the potential as well as challenges, includ

-

ing the pupils’ need for teacher prompts to activate learning. e ndings

emphasise the importance of supporting the development of pupils’ self-

regulation skills in ICT-facilitated boundary-crossing learning activities.

Minna Kukkonen and Jari Lavonen describe a concrete example of

school-community collaboration facilitated through ICT tools in their

paper “Crossing classroom boundaries through the use of collaboration

supporting ICT: A case study on school - kindergarten - library - senior

home partnership”. e design-based research serves to show that the

ICT tools, along with a sound model of collaboration, provide vast op

-

portunities to involve pupils at school in activities closely intertwined with

their community, while supporting the development of important skills,

competences, and, perhaps most importantly, citizenship.

Similarly, schools and homes can also be perceived as forming partner

-

ships. Tiina Korhonen’s and Jari Lavonen’s paper “Crossing school-fam-

ily boundaries through the use of technology” provides ideas about how

schools might actively develop their relationships with parents. Again,

design=based research provides the model for exploring and developing

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Human Eorts

12

home-school collaboration through technology. e authors identify ar-

eas of communication and collaboration, on the one hand, and areas of

support for learning, on the other hand, in which technology serves to

mediate home-school involvement.

Part and parcel of teacher change agency is the teacher’s familiarity with

e-learning tools that can be harnessed to leverage change across teaching

and learning and across dierent levels, i.e., the individual, school, and

education system levels. In their paper “Teachers’ capacity to change and

the ICT environment: Insights from the ATEPIE Project”, Jelena Radisic

and Jasminka Marcovic explore teachers’ conceptions of change agency

in the Balkan region.

e papers in the second section explore how technology creates new

practices in higher education. e new practices are here viewed in terms

of the benets and challenges related to the use of ICT in schools, a tool

that promotes students’ self-direction and reection, and participation in

various learning spaces. Two of the papers focus on the context of teacher

education, which prepares teachers to work in increasingly complex so

-

cieties, but also on the increasingly versatile teaching and learning tools

at their disposal. Anne Huhtala’s paper “Prospective teachers and new

technologies: A study among student teachers” argues for the necessity of

preparing future teachers to condently utilize ICT tools in their teaching.

It analyses student teachers’ attitudes towards using ICT and identies the

benets and challenges of ICT as envisioned by these prospective teachers.

e paper “E-Portfolio as a tool for guiding higher education student

growth to entrepreneurship” by Tarja Römer-Paakkanen describes an eort

to develop a portfolio and reection tool for promoting entrepreneurship

among students. e paper provides valuable insight into the develop

-

ment process of an e-tool for others who are interested in developing tools

that foster students’ self-directed learning and promote reection, both of

which are important 21

st

century skills and competences.

In her paper “Aordance as a key aspect in the creation of new learn

-

ing” Susanne Dau explores the aordances of dierent learning spaces

in blended learning environments in an attempt to understand what the

driving forces behind students’ learning are in these dierent spaces. With

the increasing variety of learning spaces and platforms, there is still the

13

Prologue: Crossing Boundaries for Learning

need to recognize how face-to-face spaces may contribute to the overall

learning experience. By increasing our understanding of the aordances

of dierent contexts and spaces and the roles that students take in these

spaces, teacher educators can support the learning of prospective teachers.

ese student teachers will work with pupils who exibly shift spaces and

tools, and it will become more and more important for them to reect on

their learning experiences in order to understand the realities in which

their future pupils navigate and learn.

In the third section, “Getting along with Dierent Learners”, the au

-

thors return to fundamental questions of education that are now ever so

timely in our global community. e 21

st

century skills, such as infor-

mation literacy, critical thinking, collaboration, and problem-solving are

intertwined with the values and understandings of core competencies

that future generations must be equipped with, but how do teachers and

educators understand and approach democracy and values education?

rough his paper “Conicting ideas on democracy and values educa

-

tion in Swedish teacher education,” Björn Åstrand analyses this question

through the Swedish case and reminds us of the historically and culturally

rooted nature of education and education policy.

In the last paper, “Demands and challenges - Experiences of Ethiopian

rural school teachers”, Kati Keski-Mäenpää provides a glimpse of another

type of context, namely rural schools in Sub-Saharan Africa, where schools,

teachers, students, and their families struggle with a broad range of severe

challenges, not least of all poverty. is study reminds us that even though

ICT tools oer great promise for learning in a wide variety of contexts,

there are parts of the global community that lack the infrastructures and

resources necessary to take advantage of these opportunities. However,

the skills and competences necessary in these environments may not dier

that greatly from what is termed 21

st

century skills, and democracy and

values education is no less of an important question in these contexts. In

our minds, this study raises questions about boundary crossing between

developed and developing countries, as well as between school reality and

policy making.

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Human Eorts

14

References

Ananiadou, K. & Claro, M. (2009). 21st century skills and competences for new mil-

lennium learners in OECD countries. OECD education working papers, No. 41.

OECDPublishing. http://www.oecdilibrary.org/docserver/download/5ks5f2x078kl.

pdf?expires=1391516958&id=id&accname=guest&checksum=1BF52B0FB52897

4886798A2CEB767DDB. Retrieved 8.11.2013

Binkley, M., Erstad, O., Herman, J., Raizen, S., Ripley, M., Miller-Ricci, M. & Rumble,

M. 2012. Dening twenty‐rst century skills. In Patrick Grin, Barry McGaw &

Esther Care (Eds.) Assessment and teaching of 21st century skills. Dordrecht: Springer,

17–66.

Grin, P., Care, E. & McGaw, B. 2012. e changing role of education and schools.

In Patrick Grin, Barry McGaw & Esther Care (toim.) Assessment and teaching of

21st century skills. Dordrecht: Springer, 1–16.

Crossing Boundaries

through Technology

Part I

17

1 Toward Global Sharing Pedagogy

1

Toward Global Sharing Pedagogy

Hannele Niemi and Jari Multisilta

Abstract

Learning and learning environments have changed, and are still continu-

ously changing. Many changes are connected with information and com-

munication technologies. In this article, we analyze changes in learning

concepts and knowledge creation, and the types of skills that learners will

need in the future. New requirements are examined from a working life

perspective. On the basis of these changes, we introduce a new pedagogi

-

cal concept for teaching and learning in schools; global sharing pedagogy

(GSP). e aim is to engage students in learning through four mediators:

(1) Learner-driven knowledge and skills creation; (2) collaboration; (3)

networking; and (4) digital media competencies and literacies. As an ex

-

ample, we present the applications of GSP in digital storytelling. Finally,

we discuss the importance of how learners are prepared for the future

global world.

Keywords: Technology, Global, Learning, Pedagogy, School, ICT

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Human Eorts

18

Introduction

Finland was one of the leading global information societies in the 1990s,

but this leading edge status ended with the arrival of the new millennium.

Since 2006 (Brese & Carstensa, 2009), evidence has been growing to show

that applications of information and communication technology (ICT)

have decreased to moderate levels in Finnish schools, while student use of

new communication technology outside of schools has increased. Students

use computers and social media in their everyday lives, but schools do not

necessarily provide technological learning environments as eectively as

they could (Ubiquitous Information Society Advisory Board, 2010). ere

are also many indications that teachers do not have the skills to apply

technology in new learning environments, which today typically include

a strong social media component (Niemi, 2011). In Finnish society and

schools, the use of technology is now under a reform process. As one as

-

pect of these reform activities, a national program, “Learning Solutions”

(2011-2015), was established to seek new concepts and practices for using

technology as a tool in learning settings that are radically changing (Tekes,

2013). rough its calls for action, the program had accepted almost 20

projects by 2013, all of which had the same aim: To assess how dierent

partners, such as students, teachers, researchers, and public and private

sectors can more eectively develop the pedagogical use of ICT in Finnish

schools, and equip students with skills for the 21

st

century. One of these

projects is “Finnable 2020”, which aims to develop the idea of a boundless

classroom in a global world. e main purpose of the project is to nd new

principles and practices to show how schools can cross borders of formal

and informal learning settings, and to encourage dierent learners to work

together, locally and globally.

In this article, we aim to describe the type of theoretical basis that is

required for new practices when crossing boundaries of traditional class

-

rooms. e Finnable 2020 project has created the global sharing pedagogy

(GSP) model for its theoretical framework. First, we analyze the change

in the global world; it has been claimed that this change means that a

new pedagogical concept is required. We will then introduce the main

19

1 Toward Global Sharing Pedagogy

elements of GSP. Finally, we provide some examples of the way in which

the GSP model has been locally and globally implemented in 21st century

educational settings, using technological solutions.

Megatrends of Changing Learning

and Learning Environments

Boundless Life-Wide Learning

e concept of learning has gone through a multi-layered process of rede-

nition in recent years. It is regarded as an active individual process, whereby

learners construct their own knowledge base. Learning is also increasingly

viewed as a process that is based on sharing and participation with dier

-

ent partners in a community, and as a holistic constructing process that

is interconnected with learners’ emotional, social, and cultural premises

(Cole, 1991; Salomon, 1993; Cole & Cigagas, 2010; Niemi, 2009; Säljö,

2012; Hakkarainen et al., 2013). e concept of “life-long learning” is

more of a life-course process. We learn in dierent situations and areas of

life that are cross-boundary. Learning and knowledge are no longer the

monopolistic domains of schools, or even universities. In our modern so

-

cieties, there are many forums of learning, which may be called learning

spaces, and working life and work organizations are important learning

spaces (Nonaka & Konno, 1998; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Nonaka

& Toyama, 2003). Technology-enriched learning tools and spaces with

mobile technology, Web 2.0 applications, social media, and all existing

digital resources create a powerful arena for learning, both in formal and

informal education settings (Multisilta, 2012). Our learning is life-wide,

and consists of vertical life-course learning, as well as the horizontal di

-

mensions of learning. is means that there are continuous processes of

learning: vertically, throughout various ages, and horizontally, in cross-

boundary spaces of life (Niemi, 2003). Learning is not limited to certain

ages or institutions.

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Human Eorts

20

21

st

Century Skills as the Aim of Educational Systems

e way to prepare a new generation for the future, its working life, and

life-wide learning has become as an urgent topic on the agenda of edu

-

cational systems (e.g., Binkley et al., 2012). e European Union (2006)

has dened the most important core competencies, and the Organisation

for Economic Co-operation and Development (Grin 2013; Grin, Mc

-

Gaw, & Care, 2013), as well as many global organizations, have identied

necessary 21

st

century skills. e most important message is that schools

must seek new forms of teaching and learning. Many discussions and

documents have proposed ways to face the future, and have delineated the

roles of schools and teachers in these changing contexts (e.g., Bellanca &

Brandt, 2010; Grin, McGaw, & Care, 2012). Anders Schleicher (2012)

argued that “Everyone realises that the skills that are easiest to teach and

easiest to test are now also the skills that are easiest to automate, digitise

and outsource. Of ever-growing importance, but so much harder to de

-

velop, are ways of thinking - creativity, critical thinking, problem-solving,

decision-making and learning; ways of working – including communica

-

tion and collaboration; and tools for working – including information

and communications technologies”.

Although denitions of 21

st

century skills vary, there are some com-

monalities. e most important factor is that students should have the

capacity to learn throughout their lives, and that education should provide

the skills and mental tools to enable them to do so. Inquiry and knowledge-

creation abilities are the most crucial, but they should be connected with

analytical and critical thinking skills, as well as creativity. Students should

have the capability to ask questions, and not simply seek or repeat ready

answers. ey need the ability to work independently, but also, increas

-

ingly, collaboratively. Life is ever more bound up with technology; learning

environments are continuously changing, and ICT provides many new

learning opportunities.

21

1 Toward Global Sharing Pedagogy

Working Life is changing toward Interconnectedness

Friedman (2005) has described our global world as at. He applied the

concept to the 21

st

century to describe the ways in which globalization

has changed core economic concepts. In his opinion, this attening is

a product of a convergence of the personal computer with ber-optic

micro cables, and the rise of work-ow software. He termed this period

“Globalization 3.0”, dierentiating it from the previous “Globalization

1.0” (in which countries and governments were the main protagonists),

and “Globalization 2.0” (in which multinational companies led the way

in driving global integration).

Friedman recounted many examples of companies based in India and

China, which, by providing a range of labor from typists and call center

operators, to accountants and computer programmers, have become inte

-

gral parts of the complex global supply chains for companies. e at world

is increasing social practice in all domains of life, not only in the global

economy. New technology and social media expand our communication

without any real limitations. Ramirez, Hine, Ji, Ulbrich, and Riordan

(2009) proposed that students need experiences and competencies to de

-

termine how to work in the at world. We also have evidence to suggest

that Web 2.0 technologies facilitate the acquisition of the skills required

to succeed in a new working life (e.g., Siemens, 2005).

e research group at the Institute for the Future (Davies, Fidler &

Gorbis, 2011) analyzed how work places will change in the coming years.

e qualities are based on a scenario that our global world will be increas

-

ingly connected. is increased global interconnectivity puts diversity

and adaptability at the center of organizational operations. Workplace

robotics nudges human workers out of rote, repetitive tasks, and new

media ecology requires new literacies. e group has identied the most

important skills that workers will need in the future, in which working

life will be connected with technology, but requires far more than tech

-

nological skills. In addition to identifying those abilities needed to use

new devices and technological applications, the research group (Davies,

Fidler & Gorbis, 2011) summarized the following skills as being the most

important: sense-making, social intelligence, novel and adaptive thinking,

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Human Eorts

22

cross-cultural competency, computational thinking, new-media literacy,

transdisciplinarity, design mindset ability, cognitive-load management,

and virtual collaboration. Skills and abilities will be related to higher-level

thinking, and social relationships that cannot be easily transferred to ma

-

chines, and which will enable us to create unique insights, will be critical

to decision-making. Workers will require social skills that enable them

to collaborate and build relationships of trust locally, as well as globally,

with larger groups of people in a variety of settings. Workers must also

be capable of responding to unique, unexpected circumstances that may

occur at any moment (Autor, 2010), and they will also require an ability

to understand concepts across multiple disciplines. New media literacy

is a necessary aspect of work, including critical reading and production

skills with regard to the many forms of media. is requirement will be

increased (Davies, Fidler & Gorbis, 2011), and in complex work envi

-

ronments cognitive load management is becoming urgent. Workers must

have an ability to discriminate and lter information for importance, and

to understand how to maximize cognitive functioning using a variety of

tools and techniques. Working environments view workers as agents that

take a design approach to work. It is usual for us to already create, modify,

and customize products and our environments to t to our needs. Work

-

ers are also members of virtual teams. Emerging technologies make it

easy to collaborate, despite physical distance. According to Davies, Fidler

and Gorbis (2011), the “virtual work environment demands a new set

of competencies”. Among these competencies are “the ability to develop

strategies for engaging and motivating a dispersed group”. For example,

video games and gamication could be used in motivating future virtual

teams (Davies, Fidler & Gorbis, 2011). We may conclude that teachers

and schools are at the forefront of new ways to help students to achieve

those skills and abilities that will be necessary in their future.

23

1 Toward Global Sharing Pedagogy

Knowledge Ecosystem

Today, knowledge creation is viewed as a non-linear, dialectical process,

with dierent partners and stakeholders. It is also an interaction with

technology-based learning environments and devices, which can be called

cultural artifacts. It is an interactive process, in which application of knowl

-

edge is no longer a one-directional process. Rather, it is a joint process,

whereby all partners, learners, experts, teachers, and other practitioners,

as well as representatives of companies and researchers, work together in

a complementary manner, seeking evidence for the creation of new tools

and improved learning practices.

Learning has increasingly been viewed as being embedded within a

social context and framework (Reynolds, Sinatra, & Jetton, 1996, p. 98;

Cole, 1991). Social perspective theories have variously been called social

constructivism, sociocultural perspective, socio-historical theory, and so

-

cio-cultural-historical psychology. Although the views of social perspective

theorists are diverse, each theorist posits that learning occurs through the

mediation of social interaction. Rather than use the terms acquisition and

representation, social perspective theorists regard knowledge as constructed

by, and distributed among, individuals and groups, as they interact with

one another and with cultural artifacts, such as pictures, texts, discourse,

and gestures. Knowledge is not an individual possession, but is socially

shared, and emerges from participation in social activity.

When dening knowledge creation as an interactive process, we see

that all educational settings, including schools, should prepare students

for “virtuous knowledge sharing” (European University Association, 2007,

p. 21). is notion is built on the conviction that creative knowledge

production is a sharing process. Instead of merely solving problems, indi

-

viduals and organizations create and dene problems, develop and apply

knowledge to solve the problems, and then further develop new knowledge

through the action of problem-solving. e organization and individuals

grow through such a process (Williams, Karousou, & Mackness. 2011:

Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995; Nonaka & Konno, 1998; Nonaka & Toyama,

2003). According to Nonaka & Toyama (2003), and knowledge-creation

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Human Eorts

24

is a transcending process, through which entities (individuals, groups,

organizations, etc.) transcend the boundary of the old into a new self by

acquiring new knowledge. In the process, novel conceptual artifacts and

structures for interaction are created, which provide possibilities, as well

as constrain the entities, in consequent knowledge creation cycles.

We can discuss a “knowledge ecosystem” in which all partners, learning

resources, and stakeholders provide additional value to each other by shar

-

ing and collaboration (Multisilta, 2012). In learning ecosystems, people

work together and expand their learning through social collaboration and

interaction with cultural artifacts. It means moving from static, transmit

-

ted content to knowledge that is ever-renewable and often constructed

jointly with other learners. Learning is a dynamic concept that depends on

learners’ epistemological propositions and social-cultural contexts (Cole

& Cigagas, 2010; Niemi, 2009; Säljö, 2010, 2012).

e reciprocal relationship between a human being and cultural artifacts

forms the grounds for development, which is not a straight path of quan

-

titative gains and accumulations. Social perspective theories emphasize

the role of social and cultural contexts in cognition. ey highlight the

eects of the social framework on our beliefs, concepts, and construction of

knowledge. Learning is embedded within a social context and framework,

and is a mutual interaction between human beings and cultural artifacts.

Salomon (1993) presented the concept of distributed cognition to de

-

scribe how the individual dierences between human beings, and their

own knowledge constructions created by their minds, are acknowledged.

Each individual has potential, but how this potential is developed and

activated depends on cultural symbol systems, and how such a joint sys

-

tem interacts in learning. Salomon views this joint system as one in which

learners interact with one another in a spiral-like manner. “An individual’s

inputs, through their collaborative activities, aect the nature of the joint,

distributed system, which in turn aects their cognitions such that their

subsequent participation is altered, resulting in subsequent altered joint

performances and products” (Salomon, 1993, p. 122). In virtual learn

-

ing contexts, distributed cognitions oer enormous opportunities to the

minds of students, and to culturally-constructed virtual artifacts (e.g.,

25

1 Toward Global Sharing Pedagogy

knowledge, sounds, visual images, human communication) in reciprocal

and interactive relationships.

New Learning Spaces Require Engagement

and Self-Organized Learning

e capacity to learn is not only a cognitive phenomenon. It is also an

emotional and social process (Boekaerts, 1997; Pintrich, 2000; Pintrich &

Ruohotie, 2000). We view learning as a holistic, constructive process that

is interconnected with learners’ emotional, social, cultural, and ethical real

-

ity. In technological environments, learners face all of these components,

and very often must take an active role without the direct supervision or

guidance that is available in face-to-face learning environments. Tech

-

nological environments provide open access to knowledge and learning,

but they also require a student to have the capacity to manage their own

learning; learners must have an awareness of how to manage their learning

processes. In learning psychology, we have a long tradition that provides

clear evidence that individuals need skills to steer their own learning pro

-

cesses. In the light of self-regulation research, self-regulated learners have

a large arsenal of cognitive and metacognitive strategies that they readily

deploy, when necessary, to accomplish academic tasks. In addition, self-

regulated learners have adaptive learning goals, and are persistent in their

eorts to reach these goals (Schunk & Zimmerman, 1994). Finally, self-

regulated learners are procient at monitoring and, if necessary, modifying

the strategy they use in response to shifting task demands. Self-regulated

learners are metacognitively active participants in their own learning (Pin

-

trich & Ruohotie, 2000).

Students control their learning through metacognition, and also use

cognitive and resource management strategies. Pintrich (2000) and Pin

-

trich and McKeachie (2000) introduced important control strategies in

learning tasks. ey grouped strategies into three broad categories: cog

-

nitive, metacognitive, and resource management. e cognitive category

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Human Eorts

26

includes strategies related to a student’s learning or encoding of material,

as well as strategies to facilitate retrieval of information. e metacognitive

strategies involve those related to planning, regulating, monitoring, and

modifying cognitive processes, while the resource management strategies

concern a student’s method of controlling resources (i.e., time, eort, out

-

side support) that inuence the quality and quantity of their involvement

in the task. Davies, Fidler and Gorbis (2011) described this as the ability

to manage the cognitive load.

In technological environments, self-regulated learning means that stu

-

dents use their cognition, as well as resource management skills. Respec-

tively, new technology provides tools to support and strengthen a learner’s

capacity to monitor their own learning, and also seek resources through

collaboration.

Jones, Valdez, Nowakowski, and Rasmussen (1994) suggested that suc

-

cessful, engaged learners are responsible for their own learning. ese

students are self-regulated, and are capable of dening their own learning

goals, and evaluating their own achievements. ey are also energized by

their learning; their joy in learning leads to a lifelong passion for solving

problems, understanding, and taking the next step in their thinking. ese

learners are strategic, in that they know how to learn and are capable of

transferring knowledge to solve problems creatively. Engaged learning

also involves being collaborative, that is, valuing and having the skills to

work with others.

Taylor and Parsons (2011) analyzed what student engagement might

be. ey introduced several types of engagement: academic, cognitive,

intellectual, institutional, emotional, behavioral, social, and psychological.

After exploring numerous denitions, they concluded that the following

criteria characterize engagement:

1. Learning that is relevant, real, and intentionally interdisciplinary, at

times moving learning from the classroom into the community.

2. Technology-rich learning environments, not just computers, but all

types of technology, including scientic equipment, multimedia re

-

sources, industrial technology, and diverse forms of portable commu-

nication technology.

27

1 Toward Global Sharing Pedagogy

3. Learning environments that are positive, challenging, and open, some-

times called “transparent” learning climates, encourage risk-taking and

guide learners toward co-articulated high expectations. Students are

involved in assessment for, and of, learning.

4. Collaboration via respectful “peer-to-peer” type relationships between

students and teachers.

Toward Global Sharing Pedagogy

e Finnable 2020 project has drafted a model of the GSP for promoting

21st century skills in schools. e aim has been to connect megatrends

of changes in learning concepts, knowledge creation, and working life

with teaching and learning. e GSP is based on socio-cultural theories.

Learning is viewed as a result of dialogical interactions between people,

substances, and artifacts (Pea, 2004; Cole & Cigagas, 2010; Säljö, 2012;

Hakkarainen, Paavola, Kangas, & Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, 2013). e

primary objective is to strengthen student engagement in learning and

mediate students as they become active learners and knowledge creators in

changes they are facing already, and will increasingly face in their future.

However, engagement is not viewed only as an end. It is also a means for

further learning. It is regarded as a motivational component that consists

of the emotional states of students, such as the joy and fun experienced in

learning, as well as qualities that are typical of self-regulated learning. It

includes commitment to learning tasks, and a willingness to make eorts

to achieve an objective (Pintrich, 2000; Pintrich & McKeachie, 2000).

Vygotsky (1978) introduced the idea of tools, symbolic and social me

-

diators, to the analysis of the learning process, and dened the role of

mediators as being to select, change, amplify, and interpret objects to the

learner (1978, 67). e framework of GSP has sorted mediators into four

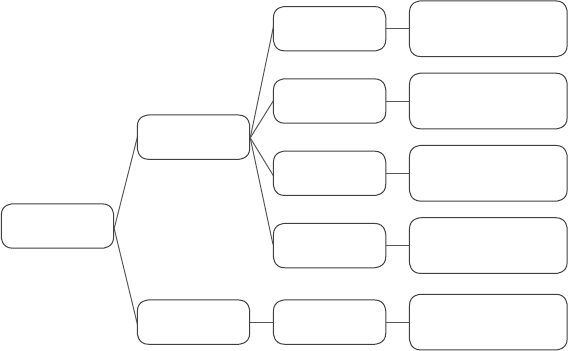

categories (Figure 1): 1) Learner-driven knowledge and skills creation; 2)

collaboration; 3) networking; and 4) digital media competencies and literacies.

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Human Eorts

28

Figure 1. Mediators in global sharing pedagogy

e role of mediators is very interactive. ey are interconnected, and

can act as both means and ends. For example, according to Multisilta and

Perttula (2013), when students learn using digital technologies, these tech

-

nologies enrich learning experiences, and contribute to the continuum of

learning. e use of the technology is an experience in itself, but it also

provides new skills that can be used in following learning situations.

Learner-driven knowledge and skills creation is a mediator that pro

-

vides learners with symbolic tools for the development of active learning

methods and metacognitive skills. is is a dynamic process in which

learners, guided by reection and metacognition, manage their thinking

and learning resources. Learners require strategic skills to manage their

own learning and create new knowledge, both individually and collabo

-

ratively (Pintrich & McKeachie 2000; Nevgi, Virtanen, & Niemi, 2006).

Schools and teachers should encourage students to engage in this type of

independent learning (Niemi, 2002; Scardamalia, 2002; Scardamalia &

– Critical thinking

– Creativity

– Argumentation

– Learning to learn skills

– Ethics and values

– Learning from others

– Sharing ideas and expe-

riences

– Social skills

– Cultural literacy and

understanding

– Help seeking and help

giving

– Content creation

– Critical content interpre-

tation and validating

– Social media skills

Collaboration

Digital

Literacy

Knowledge and

skills creation

Networking

Student

Engagement

29

1 Toward Global Sharing Pedagogy

Bereiter, 2003). Learning aects students cognitively, emotionally, socially,

and morally, and the more independent and self-regulating students are,

the more they must also be aware of, and employ, ethics and values. Me

-

diation toward student-driven knowledge creation consists of dierent

kinds of symbolic tools, such as critical thinking, creativity, argumenta

-

tion, “learning to learn” skills, and ethics and values.

Collaboration is a social mediator that allows or requires students to

work together (Hull et al., 2009; Pea & Lindgren, 2008; Rogo, 1990;

Wells 1999). It ensures that they can learn and work in the global world

in the future; they must develop the following competencies beyond the

purely “cognitive”: social skills, cultural literacy and understanding, help-

seeking, and help-giving strategies.

Networking is a social mediator that uses synergy of expertise of other

people and also provides tools for intercultural learning (Starke-Meyerring,

Duin, & Palvetzian, 2007; Starke-Meyerring & Wilson, 2008). Learning

is a continuous process of dialogical interaction with other people and

cultural artifacts. In distributed cognitions and interaction with dierent

artifacts, people introduce remarkable value that enhances their learning

and competencies. ese processes are mutually constitutive. All learners

are also contributors. us, networking means learning from others, as

well as sharing ideas and experiences.

Digital media competencies and literacies is primarily a tool mediator

that enriches learning through new technology environments, but it can

also consist of social and symbolic mediators though dierent kinds of

digital environments (Säljö, 2012). In technological environments, learn

-

ers are both content producers and consumers. As such, they need the skills

to study and work in digital environments. ey must also critically assess

and validate the knowledge they nd and create; they must be account

-

able to the norms of discourse and argumentation established by the adult

communities of practice in each discipline. ey also require skills in the

creation and discussion of social media, and in promoting ethical behavior

in these media environments. Mediation of digital media competencies

and literacy consists of the following skills that schools should provide

to students: content creation, with critical content interpretations and

validation, and social media skills that are part of digital environments.

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Human Eorts

30

How to apply GSP in teaching and learning

e GSP model has been applied in the “Digital Storytelling” project,

which was a subproject of Finnable 2020. Students (n= 319) in three coun

-

tries created digital stories with video cameras and the MoViE (Mobile

Video Experience) platform (http://www.nnable./digital-storytelling.

html) for creating and sharing collaboratively produced video stories in

Finland, Greece, and California. MoViE enables users to record video

clips using their mobile devices (phones, tablets, digital cameras, etc.),

upload videos to the MoViE web site, and create video stories using all

the clips gathered by themselves and their collaborators (Multisilta &

Mäenpää, 2008; Multisilta, Perttula, Suominen, & Koivisto, 2010; Mul

-

tisilta, Suominen, Östman, 2012; Tuomi & Multisilta, 2010, 2012). Ex-

isting video clips can also be remixed to create new video stories, and the

content of the videos is not limited by the MoViE. Teachers and students

can create videos that t their needs and support learning, both in and

outside the classroom. e purpose was that students would have interna

-

tional partners with whom they could share their videos, and could receive

comments and feedback from their local and/or international peers. An

assumption was that video products are artifacts that challenge users to

learn more and step outside of their earlier proximal zone of learning, and

that media-sharing environments would add to learners’ engagement (Pea

& Lindgren, 2008; Lewis, Pea, & Rosen, 2010; Multisilta, Suominen, &

Östman, 2012; Multisilta & Pea, 2012). e results (Niemi & Multisilta,

2014) provided good support for the idea that digital storytelling has a

great eect on students’ motivation and enthusiasm. ese components

included both fun and commitment to hard work. e greatest predictor

of the mediators of engagement was the MoViE platform, which provided

an opportunity to create, shoot, and remix one’s own story in collabora

-

tion with a peer group. e second greatest predictor was collaborative

group work; students learned in collaborative processes when producing

their videos.

GSP with its mediators also highly eectively predicted students’ learn

-

ing outcomes, which were primarily 21

st

century generic skills, such as

31

1 Toward Global Sharing Pedagogy

problem-solving, argumentation, decision-making, and cooperation.

All components of GSP (Niemi & Multisilta, 2014): (1) Learner-driven

knowledge and skills creation; (2) collaboration; (3) networking; and (4) digi

-

tal media competencies and literacies had a high predictive eect on student

learning outcomes, providing support for the model. In particular, active

learning methods, such as learner-driven knowledge creation and MoViE

as a digital media tool, were very important (Niemi & Multislta, 2014).

Learning is acknowledged in Europe, as well as globally, as the very core

of economic development (Conçeicăo, Heitor, & Lundwall, 2003; Binkley

et al., 2012). ere is a great trust in the power of knowledge and learning.

However, there is also a growing concern: Who is becoming empowered

and who is not? e real danger emerges when young people drop out of

learning pathways. In our global world, there is a growing polarization

between people who have rich learning environments and the abilities to

learn new competencies, and people who are not in this position and do

not have these skills. We must create new solutions for the use of technol

-

ogy to empower dierent learners, and help them become active learners

and citizens. It also means making eorts to help individuals nd mean

-

ingfulness in their life.

Meaningfulness is very often linked to active learning and engagement

in learning. Taylor and Parsons (2011) analyzed several denitions of

engagement, and despite dierences, the common feature is that engage

-

ment is linked to a student’s active role: students design, plan, and carry

out their projects. Meaningfulness can also be promoted when students

publicly exhibit a project to themselves, to the community, or to a cli

-

ent. It has a transformative eect on their perception of themselves, their

relationship with learning, and their sense of place in the world around

them. e main function of schools is to prepare students for enquiry,

which will help them take an active role in their lives.

All over the world, 21

st

century skills have become an urgent topic on

the agenda of educational systems (Binkley et al., 2012). Schools are re

-

quired to seek new forms of teaching and learning for the future. Many

discussions and documents propose ways to face the future and delineate

the roles of schools and teachers in these changing contexts. Technology is

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Human Eorts

32

not an aim in and of itself, but it can be an important tool for empower-

ing students for what lies ahead.

Why should we prepare our students for global collaboration and net

-

working? Why is the pedagogical model “global”? ICT crosses borders.

Social media has broken all borders, nationally and internationally. e

Internet provides learning resources and databases that are accessible across

and within nations. In many areas of life, people depend on international

knowledge production, and working environments are increasingly global.

Our students will be both cosmopolitan learners and workers. is means

that one of the important aims of schools should be to prepare them for

a collaborative culture and the idea of sharing. Learner concepts regard

-

ing their agency in the global world mean that they should become active

global citizens, providing their contribution in the joint world. is agency

can be achieved only by having authentic experiences in schools across

borders and cultures. e GSP proposes that schools possess a teaching and

learning culture that allows and encourages the entire school community

to be open to collaboration, networking, active knowledge creation, and

digital literacy. is also means active interactions with partners outside

the school, and connections with other schools, both locally and globally.

References

Autor, D. (2010). e Polarization of Job Opportunities in the US Labor Market. Center

for American Progress and e Hamilton Project, April 2010.

Bellanca, J. & Brandt, R. (2010). 21st century skills: Rethinking how students learn.

Bloomington, IN: Solution Tree.

Binkley, M., Erstad, O., Herman, J., Raizen, S., Ripley, M., Miller-Ricci, M., & Rumble,

M. (2012). Dening twenty-rst century skills. In P. Grin, B. McGaw, & E. Care

(Eds.), Assessment and teaching of 21st century skills (pp. 17–66). Dordrecht: Springer.

Boekaerts, M. (1997). Self-regulated learning: A new concept embraced by research-

ers, policy makers, educators, teachers, and students. Learning and Instruction, 7 (2),

161–186.

Brese, F., & Carstens, R. (Eds.). (2009).Second information technology in education study:

SITES 2006 user guide for the international database. Amsterdam: IEA.

33

1 Toward Global Sharing Pedagogy

Cole, M. (1991). Conclusion. In L. B. Resnick, J. M. Levine, & S. D. Teasley (Eds.),

Perspectives on socially shared-cognition (pp. 398–417). Washington, DC: American

Psychological Association.

Cole, M., & Cigagas, X. E. (2010). Culture and cognition. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.),

Handbook of cultural developmental science (pp. 127–142). New York, NY: Psychol-

ogy Press.

Conçeică o, P., Heitor, M. V., & Lundwall, B-Å. (Eds.) (2003). Innovation and competence

building with social cohesion for Europe. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Davies, A. Fidler, D., & Gorbis. D. (2011). Future Work Skills 2020. Palo Alto, CA:

Institute for the Future for University of Phoenix Research Institute. Retrieved Feb.

19, 2014 http://www.iftf.org/uploads/media/SR1382A_UPRI_future_work_skills_

sm.pdf

European University Association. (2007). Creativity in higher education: Report on the

EUA creativity project 2006–2007. Brussels: European University Association.

European Union (2006). Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the

Council of 18 December 2006 on key competences for lifelong learning. 2006/962/

EC. Ocial Journal of the European Union. 30.12.2006.

Finnable 2020. (2013). Finnable 2020 Research Project. University of Helsinki. http://

www.nnable.

Friedman. T. L. (2005). e world is at: A brief history of the twenty-rst century. New

York: omas L. Friedman.

Grin, P., McGaw, B., & Care, E. (Eds.). (2013). Assessment and teaching of 21st cen-

tury skills (pp. 17–66). Dordrecht, Germany: Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2324-5_2

Grin, P. (2013, August). e assessment and teaching of 21st century skills (ATC-

S21S

TM

). Presentation at TERA & PROMS Conference, Taiwan.

Grin, P., McGaw, B., & Care, E. (2012). e changing role of education and schools.

In P. Grin, B. McGaw, & E. Care (Eds.), Assessment and teaching of 21st cen-

tury skills (pp. 1–16). Dordrecht, Germany: Springer Science+Business Media B.V.

doi:10.1007/978-94-007-2324-5_2

Hakkarainen, K., Paavola, S., Kangas, K., & Seitamaa-Hakkarainen, P. (2013). Socio-

cultural perspectives on collaborative learning: Towards collaborative knowledge crea-

tion. In C. E. Hmelo-Silver, A. M. O’Donnell, C. Chan, C. A. Chinn (Eds.), e in-

ternational handbook of collaborative learning (pp. 57–73). New York, NY: Routledge.

Hull, L., Zacher, J. & Hibbert, L. (2009). Youth, risk, and equity in a global world.

Review of Research in Education, 33(1), 117–159.

Jones, B., Valdez, G., Nowakowski, J., & Rasmussen, C. (1994). Designing Learning

and Technology for Educational Reform. Oak Brook, IL: North Central Regional Edu-

cational Laboratory.

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Human Eorts

34

Lewis, S., Pea, R., & Rosen, J. (2010). Beyond participation to co-creating of meaning:

Mobile social media in generative learning communities. Social Science Information,

49(3), 1–19.

Multisilta, J. (2012). Designing learning ecosystems for mobile social media. In A. D.

Olofsson & J. O. Lindberg (Eds.), Informed design of educational technologies in higher

education (pp. 270–291). Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

Multisilta, J., & Mäenpää, M. (2008). Mobile video stories. In Proceedings of the 3rd In-

ternational Conference on Digital Interactive Media in Entertainment and Arts (DIMEA

‘08): Vol. 349 (pp. 401–406). New York, NY: ACM. Retrieved from http://doi.acm.

org/10.1145/1413634.1413705

Multisilta, J., & Pea, R. (2012). Workshop on social mobile video and panoramic video.

Retrieved from http://jarimultisilta.com/workshop2012/

Multisilta J., & Perttula, A. (2013). Supporting learning with wireless sensor data. Future

Internet 2013, 5(1), 95–112.

Multisilta, J., Perttula, A., Suominen, M., & Koivisto, A. (2010). Mobile video sharing:

Documentation tools for working communities. In Proceedings of the 8th International

Interactive Conference on Interactive TV & Video (pp. 31–38). New York, NY: ACM.

Multisilta, J., Suominen, M., & Östman, S. (2012). A platform for mobile social media

and video sharing. International Journal of Arts and Technology, 5(1), 53–72.

Nevgi, A., Virtanen, P., & Niemi, H. (2006). Supporting students to develop collabora-

tive learning skills in technology-based environments. British Journal of Educational

Technology, 37(6), 937–947.

Niemi, H. (2011). Educating student teachers to become high quality professionals: A

Finnish case. Center for Educational Policy Studies Journal Journal. 1(1), pp. 43–67.

Niemi, H. (2009). Why from teaching to learning. European Educational Research Jour-

nal, 8 (1), 1–17.

Niemi, H. (2003). Competence building in life-wide learning: Innovation, competence

building and social cohesion in Europe, (pp. 219–239). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Niemi, H. (2002). Active learning—A cultural change needed in teacher education and

in schools. Teaching and Teacher Education, 18, 763–780.

Niemi, H., & Multisilta, J. (2014, Spring, forthcoming). Digital storytelling promoting

21st century skills and students’ engagement. Technology, Pedagogy and Education.

Nonaka, I., & Konno, N. (1998). e Concept of ‘Ba ’: building a foundation for

knowledge creation. California Management Review, 40(3), 40–54.

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). e knowledge-creating company: How Japanese

companies create the dynamics of innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Nonaka, I., & Toyama, R. (2003). e knowledge-creating theory revisited: Knowledge

creation as a synthesizing process. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 1, 2–10.

Pea, R., & Lindgren, R. (2008). Collaboration design patterns in uses of a video platform

for research and education. IEEE Transactions on Learning Technologies, 1(4), 235–247.

35

1 Toward Global Sharing Pedagogy

Pea, R. D. (2004). e social and technological dimensions of scaolding and related

theoretical concepts for learning, education, and human activity. e Journal of the

Learning Sciences, 13(3), 423–451.

Pintrich, P. R., & Ruohotie, P. (Eds.). (2000). Conative constructions and self-regulated

learning. Hämeenlinna, Finland: RCVE.

Pintrich, P. R., & McKeachie, W. J. (2000). A Framework for conceptualizing student

motivation and self-regulated learning in the college classroom. In P. R. Pintrich &

P. Ruohotie (Eds.), Conative constructions and self-regulated learning (pp. 31–50).

Hämeenlinna, Finland: RCVE.

Pintrich, P. R. (2000). e role of motivation in self-regulated learning. In P. R. Pintrich

& P. Ruohotie (Eds.), Conative constructions and self-regulated learning (pp. 51–66).

Hämeenlinna, Finland: RCVE.

Ramirez, A., Hine, M., Ji, S., Ulbrich, F., and Riordan, R. (2009). Learning to succeed

in a at world: Information and communication technologies for a new generation

of business students. Learning Inquiry, 3(3), 157–175.

Reynolds, R. E., Sinatra, G. M., & Jetton, T. L. (1996). Views of knowledge acquisi-

tion and representation: A continuum from experience centered to mind centered.

Educational Psychologist, 31(2), 93–104.

Rogo, B. (1990). Apprenticeship in thinking: Cognitive development in social context.

New York: Oxford University Press.

Salomon, G. (1993). No distribution without individual’s cognition: A dynamic interac-

tional view. In G. Salomon (Ed.), Distributed cognitions: Psychological and educational

considerations (pp. 111–138). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Scardamalia, M., & Bereiter, C. (2003). Knowledge building. In J.W. Guthrie (Ed.),

Encyclopedia of education (2nd ed.) (pp. 1370–1373). New York, NY: Macmillan

Reference.

Scardamalia, M. (2002). Collective cognitive responsibility for the advancement of

knowledge. In B. Smith (Ed.), Liberal education in a knowledge society (pp. 67–98).

Chicago: Open Court.

Schunk, D., & Zimmerman, B. (1994). Self-regulation of learning and performance:

Issues and educational applications. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Scleicher. A, (2012)- Preparing teachers and school leaders for the 21st century – Ministers

and Union leaders meet on how to turn visions into reality. Posted by Andreas Schleicher

on 17-Mar-2012. Retrieved Feb. 19.2014. https://community.oecd.org/community/

educationtoday/blog/2012/03/17/preparing-teachers-and-school-leaders-for-the-

21st-century-ministers-and-union-leaders-meet-on-how-to-turn-visions-into-reality.

Siemens, G. (2005). Connectivism: A learning theory for the digital age. International

Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 2(1), 3–10.

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Human Eorts

36

Starke-Meyerring, D., Duin, A. H., & Palvetzian, T. (2007). Global partnerships: Posi-

tioning technical communication programs in the context of globalization. Technical

Communication Quarterly, 16(2), 139–174.

Starke-Meyerring, D., & Wilson, M. (Eds.) (2008). Designing globally networked learn-

ing environments: Visionary partnerships, policies, and pedagogies. Rotterdam: Sense

Publishers.

Säljö, R. (2012). Schooling and spaces for learning: Cultural dynamics and student

participation and agency. In E. Hjörne, G. van der Aalsvoort, & G. Abreu (Eds.),

Learning, social interaction and diversity - Exploring school practices (pp. 9–14). Rot-

terdam: Sense.

Säljö, R. (2010). Digital tools and challenges to institutional traditions of learning: tech-

nologies, social memory and the performative nature of learning. Journal of Computer

Assisted Learning, 26, 53–64.

Taylor, L., & Parsons, J. (2011). Improving student engagement. Current Issues in Edu-

cation, 14(1), 1-33

Tekes. (2013). Learning Solutions: Tekes Programme 2011–2015. Retrieved from http://

www.tekes./Julkaisut/tekes_learning_solutions.pdf

Tuomi, P., Multisilta, J. (2012) Comparative study on use of mobile videos in elemen-

tary and middle school. International Journal of Computer Information Systems and

Industrial Management Applications, 4, 255–266.

Tuomi, P., & Multisilta, J., (2010). MoViE: Experiences and attitudes—Learning

with a mobile social video application. Digital Culture & Education, 2(2), 165–189.

Available from http://www.digitalcultureandeducation.com/cms/wp-content/up-

loads/2010/10/dce 1024_tuomi_2010.pdf

Ubiquitous Information Society Advisory Board. (2010). ICTs in schools everyday life

project. Ministry Finnish National Plan for Educational Use of ICTs. Ministry of Trans-

port and Communication, Ministry of Culture and Education & National Board

of Education. Retrieved from http://www.edu./download/135308_TVT_ope-

tuskayton_suunnitelma_Eng.pdf (In English: http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.

kmrp.8500001)

Vygotsky, L.S. (1978). Mind in Society: the development of higher psychological processes.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wells, G. (1999). Dialogic Inquiry: Towards a Socio-cultural Practice and eory of Educa-

tion. Cambridge: University Press.

Williams, R., Karousou, R., & Mackness, J. (2011). Emergent learning and learning

ecologies in Web 2.0. e International Review of Research in Open and Distance

Learning,12(3), 39–59.

37

2 Crossing School -Family Boundaries Through the Use of Technology

2

Crossing School -Family

Boundaries Through the

Use of Technology

Tiina Korhonen and Jari Lavonen

Abstract

e aim of this study was to discover how already-available information

and communication technology (ICT) in homes and schools could be

better utilized to enhance home-school collaboration (HSC). Novel ideas

and innovations for use of existing ICT to support HSC, including innova

-

tions on learning and assessment, were generated by students, parents, and

teachers. Key data was collected from two second and third grade classes

of an elementary school in Espoo, Finland during the 2009–2010 school

year. e study was conducted using design-based research (DBR), with

both practitioners and researchers aiming to produce meaningful changes

in everyday HSC activities. During the rst phase of the study, the needs,

limitations, and ideas regarding HSC and the use of ICT in support of

HSC were collected from all participants. A preliminary analysis of the

data was discussed among teams of volunteer teachers, parents, and stu

-

dents. e teams selected candidate ideas for practical testing and further

development in two DBR cycles. After the cycles, a guide based on the

innovations was created to help other teachers, students, and parents utilize

ICT in HSC. e study results indicate a multitude of ways to use ICT

in HSC, including communication and interaction between students,

teachers, and parents, and support of student learning and growth. A novel

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Human Eorts

38

result of this study is that ICT can facilitate the practical implementation

of new types of collaboration, such as parent participation in learning at

school and student learning in their free time.

Keywords: Home-School Collaboration, ICT, Deployment and Develop-

ment of Innovations

Introduction

e use of ICT in education, including the use of Internet applications

and learning environments, has undergone rapid development during the

last 20 years. Today, students, teachers, and parents have a wide selection

of ICT tools and environments at their daily disposal. In the school, teach

-

ers and students can use ICT for learning and for information retrieval,

for individualized learning, and for interaction between the school and

its surrounding community, such as HSC (Haaparanta & Tissari, 2008).

Despite the wide availability of ICT facilities, their use has not yet

become a natural part of everyday school life. eir use does not support

teaching and learning and is limited in various collaboration situations

(OECD, 2004, 2006; Lavonen, Juuti, Aksela, & Meisalo, 2006; Younie,

2006; Hayes, 2007; Hennessy et al., 2007; European Commission, 2013).

In order to make the use of ICT a natural part of interactions between a

school and its surrounding community, ICT must be integrated into the

school’s structural and pedagogical development activities (Haaparanta

& Tissari, 2008).

In early 2011, the Finnish National Board of Education made changes to

the national-level framework curriculum, including the section concern

-

ing HSC. e new policy emphasizes the importance of HSC in support-

ing the personalized, holistic growth of students and learning outcomes.

For the rst time, the renewed curriculum includes a policy advocating the

use of ICT to enhance HSC (Finnish National Board of Education, 2011).

is study uses a DBR approach to explore the implementation and use

of ICT to support HSC. e key conjecture is that it is possible to imple

-

39

2 Crossing School -Family Boundaries Through the Use of Technology

ment ICT-based collaboration and obtain results with the ICT facilities

already available today at home and in the school. e assumption is that

this can be achieved by identifying and developing innovations on ICT

use in HSC, by involving end users in the generation and development of

ICT use ideas, and by identifying and addressing the general challenges

of ICT use and implementation.

Research Questions

e study aimed to uncover what practical possibilities are there in the use of

ICT in HSC. In addition, the study aimed to nd out how students, teach

-

ers, and parents experience ICT-supported HSC and the adoption of ICT for

HSC. In this paper, we focus on the research question concerning the pos

-

sibilities that parents, teachers, and students see for the use of ICT in HSC.

Home-School Collaboration

e key objective of HSC is to support the holistic, safe growth and de-

velopment of children and youth (Finnish National Board of Education,

2011). A closer relationship between parents and their children’s educa

-

tion and school activities has an increasingly supportive eect on child

development and academic performance (Fullan, 2007).

In this study, we describe HSC based on the six types of home and

school involvement dened by Epstein (2009): parenting, communicat

-

ing, volunteering, learning at home, decision making, and collaborating

with the community.

Key themes in HSC are partnership and shared responsibility. Important

success factors in a home-school partnership include caring, trust, and re

-

spect. A home-school partnership provides students with a feeling of being

cared for and being supported by the community, thus encouraging stu

-

dents, guiding them, and motivating them to do their best (Epstein, 2009).

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Human Eorts

40

e key challenge in HSC is taking into account the varying needs and

goals of teachers, students, and parents. e general aim is to nd ways

to arrange HSC to support the development of an individual student and

to improve the team spirit and the feeling of social relatedness within the

class (Siniharju, 2003).

e lack of available time is a challenge in HSC for both teachers and

parents. Faced with increasing class sizes, teachers must nd time for

HSC with all parents within normal working hours, while also encourag

-

ing more passive parents to collaborate. Many parents would like to be

better informed about their children’s progress and school events. At the

same time, parents also struggle to nd time for HSC (Siniharju, 2003).

For successful HSC, respect for the thoughts, opinions, and wishes of

all stakeholders (teachers, students, and parents) is essential. e goal is

that through a long-term collaborative development activity, more families

and teachers will learn to work with one another as parts of a commu

-

nity for the benet of the children. As collaborative development work is

time-consuming, to achieve good results it should be planned as a regular

activity with all stakeholders (Epstein, 2009).

ICT Use in Home-School Collaboration

as an Innovation

In this study, the various possibilities of using ICT to enable HSC and

to overcome the challenges in the use of ICT in HSC are referred to as

innovations. An innovation is an idea, practice, or object that is perceived

as new (Rogers, 2003).

In order to enter, or diuse, into actual use, these innovations should

be adopted by individual teachers, parents, and students. We analyze the

process of adoption within the framework of Rogers’ theory on the adop

-

tion of innovations (Rogers, 2003).

According to Rogers, when an individual determines whether or not

to personally accept or reject an innovation, they seek information about

41

2 Crossing School -Family Boundaries Through the Use of Technology

the innovation and actively process that information, typically with other

people in the community. Rogers divides this adoption process into ve

phases: knowledge, persuasion, decision, implementation, and conrma

-

tion (Rogers, 2003).

is study focuses on the last three phases of Rogers’ adoption process.

Specically, the study considers four key aspects of the adoption process

with the potential to aect the outcome of adoption in a positive or nega

-

tive way.

Individualization

In the re-invention of an innovation, an adopter or group of adopters

modies an available innovation to better suit their needs. rough re-

invention, the innovation is more likely to be accepted (Rogers, 2003). We

refer to such new or modied innovations created through re-invention,

or individualization, as individual innovations.

is study applies the DBR principle of generating ideas (McKenney &

Reeves, 2012) to encourage participants to re-invent innovations and thus

create novel individual innovations, which will more likely be adopted into

practice. In this study, individual innovations include the ideas of teach

-

ers, students, and parents about the use of the ICT facilities in HSC. e

innovations may include the use of ICT tools available in the classroom

or at home, such as computers, digital cameras, interactive whiteboards,

document cameras, as well as a web-based learning environment (WBLE)

called Opit, with access available to students, teachers, and parents.

Participation

Our assumption is that participation by teachers, students, and parents

in the generation and implementation of ideas will support their com

-

mitment and adoption of the innovations. is assumption is supported

by existing research, which indicates that user involvement in innovation

implementation increases the likelihood of continued use and further

development of the innovation (Rogers, 2003).

Crossing Boundaries for Learning – through Technology and Human Eorts

42