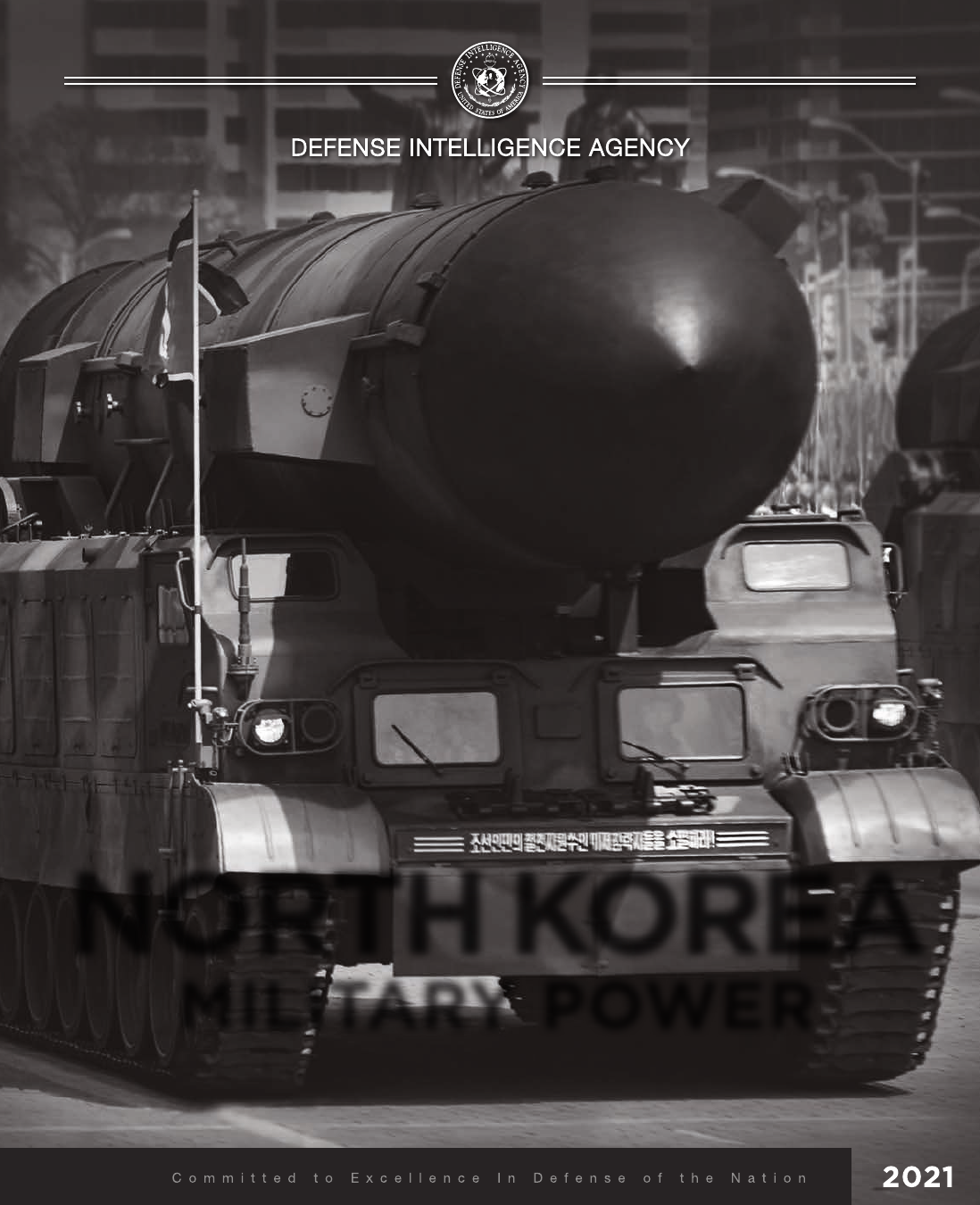

NORTH KOREA

A GROWING REGIONAL and GLOBAL THREAT

MILITARY POWER

This report is available online at www.dia.mil/Military-Power-Publications

For media and public inquiries about this report, contact [email protected]

For more information about the Defense Intelligence Agency, visit DIA's website at www.dia.mil

Information cutoff date, September 2021

Cover image, Pukguksong-2 medium-range ballistic missile paraded in Pyongyang. Source: AFP

DIA-02-1801-056

This report contains copyrighted material. Copying and disseminating the contents is prohibited without the permission of the

copyright owners. Images and other previously published material featured or referenced in this publication are attributed to

their source.

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents

U.S. Government Publishing Oce

www.bookstore.gpo.gov | Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402-0001

Phone: (202) 512-1800, toll free (866) 512-1800 | Fax: (202) 512-2104

ISBN 978-0-16-095606-5

INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

IV

PREFACE

In September 1981, Secretary of Defense Caspar Weinberger asked the Defense Intelligence Agency

to produce an unclassied overview of the Soviet Union’s military strength. The purpose was to

provide America's leaders, the national security community, and the public a comprehensive and

accurate view of the threat. The result: the rst edition of Soviet Military Power. DIA produced over

250,000 copies, and it soon became an annual publication that was translated into eight languages

and distributed around the world. In many cases, this report conveyed the scope and breadth of

Soviet military strength to U.S. policymakers and the public for the rst time. DIA also produced

similar documents describing North Korean military strength in 1991 and 1995.

In 2017, DIA began to produce a series of unclassied Defense Intelligence overviews of major foreign

military challenges facing the United States. This volume provides details on North Korea’s defense

and military goals, strategy, plans and intentions; the organization, structure, and capabilities of its

military to supporting those goals; and the enabling infrastructure and industrial base. This product

and other reports in the series are intended to inform our public, leaders and troops, the national

security community, and partner nations about the challenges we face in the 21st century.

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

V

North Korea is one of the most militarized countries in the world and remains a critical security challenge

for the United States, our Northeast Asian allies, and the international community. The Kim regime has

seen itself as free to take destabilizing actions to advance its political goals, including attacks on South

Korea, development of nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles, proliferation of weapons, and cyberattacks

against civilian infrastructure worldwide. Compounding this challenge, the closed nature of the regime

makes gathering facts about North Korea's military extremely difcult.

Just over twenty years ago, North Korea appeared to be on the brink of national collapse. Economic

assistance from former patrons in the Soviet Union disappeared; society was confronted with the death in

1994 of regime founder Kim Il Sung—revered as a deity by his people—and a 3-year famine killed almost

a million people. Many experts in academia and the Intelligence Community predicted that North Korea

would never see the 21st century. Yet today, North Korea not only endures under a third-generation Kim

family leader, it has become a growing menace to the United States and our allies in the region.

Kim Jong Un has pressed his nation down the path to develop nuclear weapons and combine them with

ballistic missiles that can reach South Korea, Japan, and the United States. He has implemented a

rapid, ambitious missile development and ight-testing program to rene these capabilities and improve

their reliability. His vision of a North Korea that can directly hold the United States at risk, and thereby

deter Washington and compel it into policy decisions benecial to Pyongyang, is clear and is plainly

articulated as a goal in authoritative North Korean rhetoric.

Equally dangerous, North Korea continues to maintain one of the world’s largest conventional militaries

that directly threatens South Korea. The North can launch a high-intensity, short-duration attack on the

South with thousands of artillery and rocket systems. This option could cause thousands of casualties

and massive disruption to a regional economic hub. Kim Jong Un’s emphasis on improving military

training and investment in new weapon systems highlights the overriding priority the regime puts on

its military capabilities.

In 2018, at the historic rst summit between Kim Jong Un and the President of the United States, North

Korea pledged to work with the United States to accomplish what it described as “the denuclearization

of the Korean Peninsula”, and committed to other measures to reduce tensions and achieve “a lasting

and stable peace regime.” In the following years, North Korea tested multiple new missiles that threaten

South Korea and U.S. forces stationed there, displayed a new potentially more capable ICBM and new

weapons for its conventional force. Additionally, there continues to be activity at North Korea’s nuclear

sites. These actions indicate that North Korea will continue to be a challenge for the United States in

the coming years. This report, is a baseline examination of North Korea and its core military capabilities,

and is intended to help us better understand the current threat Pyongyang poses to the United States

and its allies.

From North Korean Leader Kim Jong Un's Remarks at the 8th Workers’ Party

Congress, Released 9 January 2021

“Building the national nuclear force was a strategic and predominant goal. The status of our state

as a nuclear weapons state…enabled it to bolster its powerful and reliable strategic deterrent for

coping with any threat by providing a perfect nuclear shield. New, cutting edge weapons systems

were [also] developed one after another … making our state’s superiority in military technology

irreversible and putting its war deterrent and capability of ghting war on the highest level.”

1

Scott D. Berrier

Lieutenant General, U.S. Army

Director

Defense Intelligence Agency

INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

VII

CONTENTS

Introduction and Historical Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .1

Origins and Combat History of the Korean People's Army (KPA), 1948–1953 . . . . . .2

The Post–Korean War KPA, 1953–1991

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Shift to Asymmetric Capabilities, 1991–Present

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

National Military Overview . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .7

Threat Perceptions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .8

National Security Strategy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9

Political Stability

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 11

External Relations

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Defense Budget

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Military Doctrine and Strategy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Perceptions of Modern Conict

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

Military and Security Leadership

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14

National Military Command and Control

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Nuclear Command and Control

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

Core North Korean Military Capabilities . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Nuclear Weapons and Ballistic Missiles . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Program History and Pathway to Weapon Development

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Ballistic Missile Force

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Biological and Chemical Weapons

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Offensive Conventional Systems

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

National Defense

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 30

Underground Facilities

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .30

Air Defense

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 31

Coastal Defense

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .32

Electronic Warfare

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

VIII

Space/Counterspace . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 32

Cyberspace

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Computer Network Attack and Intimidation

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Cyber-Enabled Propaganda

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 33

Intelligence Collection

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Currency Generation

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Denial and Deception

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 34

Logistics and Sustainment

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 35

Human Capital

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 36

Outlook: Targeted Investments in Select Military

Capabilities

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 38

Appendix A: Strategic Force

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .40

Appendix B: Ground Forces

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 42

Appendix C: Air and Air Defense Forces

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 45

Appendix D: Navy

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .48

Appendix E: Special Operations Forces

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . 52

Appendix F: Reserve and Paramilitary Forces

. . . . . . . . . . 55

Appendix G: Intelligence Services

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 57

Appendix H: Defense Industry and the Energy Sector

. . . . . . 60

Appendix I: Arms Sales

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 67

Acronyms

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 71

INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK

X

Satellite view of the Korean Peninsula at night, 2020. Visible light emis-

sions from North Korea continue to be extremely sparse, reflecting limited

availability of electricity to most of the country outside the capital, Pyong-

yang, and the leadership’s fundamental decision to invest a large portion

of North Korea’s resources into building military power.

Image Source: NASA

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

1

Introduction/Historical Overview

he evolution of the Korean People’s

Army (KPA) from a regional military

to an aspiring nuclear force with inter-

continental strike capabilities is the result of

decades of commitment to two consistent mis-

sions given to the military by the Kim family

regime: preserve the North Korean state’s

independent existence against any external

power, and provide the means for North Korea

to dominate the Korean Peninsula. Over the

course of its existence, the KPA has seen both

the decline of some core strengths and the evo-

lution of new capabilities, but it has retained

these central roles. Although expanded in

scope, the new capabilities North Korea’s

military is developing are consistent with its

founding objectives. They are intended to hold

the United States at bay while preserving the

capacity to inict sufcient damage on the

South, such that both countries have no choice

but to respect the North’s sovereignty and

treat it as an equal.

2

North Korea’s military poses two direct, over-

lapping challenges to the United States and its

allies: a conventional force consisting mostly

of artillery and infantry that can attack South

Korea with little advance warning, and a ballis-

T

Kim Il Sung, North Korea’s first leader. Kim founded the Korean People's Army in 1948 with support and

equipment from the Soviet Union.

Image Source: AFP

2

tic missile arsenal, intended to be armed with

nuclear weapons, that is capable of reaching

bases and cities in South Korea and Japan, and

the U.S. homeland.

3

Although the conventional

threat to the South has evolved slowly over

several decades, the rapid pace of development

and testing in the nuclear and missile programs

between 2012 and 2017 has brought this sec-

ond possibility closer to reality faster than most

international observers had anticipated. These

capabilities create growing risk of a military

ashpoint in Northeast Asia that could quickly

escalate off the Korean Peninsula, possibly

across the Pacic Ocean to U.S. soil.

Origins and Combat History

of the KPA, 1948–1953

The KPA was founded in 1948 as an infantry-cen-

tric force established to provide Kim Il Sung—the

Soviet-backed North Korean leader who rose to

power after the peninsula was divided in 1945—a

means to defend his new regime, provide a plat-

form to indoctrinate his people, and allow him to

achieve dominance over the entire Korean Penin-

sula. Most of the KPA’s original equipment, sup-

port infrastructure, and training was provided

by the Soviet Union. Kim founded the KPA on a

mix of Soviet strategic and Chinese tactical inu-

ences, deriving doctrine and military thought

from Marxism-Leninism and interpreting it for a

Korean audience.

4

In 1950, Kim launched a general invasion of

South Korea with the intention of reunifying

the peninsula under Pyongyang’s rule. The

KPA drove South Korean and U.S. forces to

the southern tip of the peninsula in a matter of

weeks. Operating under a United Nations Com-

mand (UNC) established by Security Council

Resolution 84, forces and support personnel

from over a dozen countries reversed the KPA’s

advance and drove it back to the Yalu River,

which divides North Korea from China. Chi-

nese forces then intervened on North Korea’s

behalf, leading to an eventual stalemate at

the 38th parallel—today’s Demilitarized Zone

(DMZ). The Korean War remains the only sus-

tained conict in which the KPA participated

as a major belligerent. North Korea suffered

an estimated 1.5 million soldiers and civil-

ians killed in the war and endured devastat-

ing damage from aerial bombing and ground

assault.

5

These losses deeply inuenced North

Korean strategic thinking and military and

defense planning, resonating into the present

day. Although hostilities were suspended with

an Armistice Agreement in 1953, no peace

treaty was signed, and the peninsula techni-

cally remains in a state of war.

U.S. aerial bombing over Wonsan Harbor during

the Korean War. North Korea suffered massive

industrial damage in combat with United Nations

Command forces from 1950 to 1953.

Image Source: Shutterstock

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

3

The Post–Korean War KPA,

1953–1991

Rebuilding after the Korean War, North Korea

had shifted its military strategy by the 1960s to

a Maoist-style war of attrition, hoping to under-

mine the government in Seoul through covert

inltration, assassinations, and attempts to

foster Communist insurgencies.

6,7

During this

period, Kim embarked on a program to modern-

ize the KPA and posture it to defend in depth

against any foreign aggressor. In December

1962, Kim Il Sung espoused the Four Military

Guidelines: arm the entire population, fortify

the entire country, train the entire army as a

"Cadre Force" (meaning all soldiers capable

of establishing and training military units),

and modernize weaponry, doctrine, and tactics

under the principle of self-reliance in national

defense.

8,9

Early North Korean interest in

nuclear technology, which dates to the 1950s,

reached a practical stage during this period; a

Soviet-supplied research reactor went online

in 1967, and a domestically-designed reactor

began operating in 1986.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the North Korean

regime accelerated and redirected KPA mod-

ernization initiatives toward reestablishing

offensive conventional warfare capabilities.

In an August 1976 Korean Workers' Party

journal, an article entitled "Scientic Fea-

tures of Modern War and Factors of Victory"

kicked off a rare internal debate on military

doctrine by stressing the importance of eco-

nomic development and the impact of new

weapons on military strategy. The author

argued that the quality of arms and the level

of military technology dene the character-

istics of war. The primacy of conventional

warfare again became doctrine. This article

laid down several concepts that continued to

inuence North Korean operational doctrine

through the 1990s and into the 21st century;

particularly inuential was an emphasis on

operational and tactical mobility, deep-strike

capabilities, and use of the subterranean

domain throughout the depth of the battle-

eld.

10

Although these tenets remain central

to North Korean military doctrine, the abil-

ity of the state to sustain forcewide modern-

ization began to decline in the late 1980s.

Kim Jong Il, right, became leader in 1994 after the

death of Kim Il Sung, left. The younger Kim set

North Korea on course to further its nuclear and

missile programs.

Image Source: AFP

4

Shift to Asymmetric

Capabilities, 1991–Present

With the loss of direct Soviet and Chinese mil-

itary-to-military support in the early 1990s,

the beginning of a major economic decline,

and the famine in the late 1990s, accompa-

nied by advances in U.S. and South Korean

military capabilities, North Korea became

less and less likely to prevail in a conven-

tional war on the peninsula. Under new

North Korean leader Kim Jong Il, the KPA

emphasized asymmetric capabilities, such

as special operations forces, chemical and

biological weapons, and long-range artillery

postured against the predominantly civilian

population in Seoul, and renewed its empha-

sis on developing a nuclear strike capability.

Also during this period, Kim publicized the

Songun ideology—“Military First” politics —a

public reafrmation of the KPA’s centrality to

the regime. Under this philosophy, the mili-

tary became one of the dominant institutions

in North Korean society.

11

By the 1990s, North Korea was making strides

in ballistic missile development. In 1993 the

North ight-tested a new, Scud-derived medi-

um-range ballistic missile, the No Dong, and

in 1998 North Korea attempted to launch a

satellite using a prototype multistage rocket

that could support the development of lon-

ger-range ballistic missiles.

12,13

North Korea

continued to operate a nuclear reactor at

Yongbyon during this period, fueling concerns

that Pyongyang could extract plutonium for

use in nuclear weapons.

14

These developments

spurred international efforts to constrain the

growth of the North Korean nuclear and bal-

listic missile programs, rst through a bilat-

eral Agreed Framework between North Korea

and the United States and later through a

multilateral Six-Party Talks process also

involving South Korea, Japan, China, and

Russia. For a time, Kim Jong Il cooperated

with some of these initiatives, temporarily

suspending missile testing and nuclear activ-

ities and submitting to some degree of inter-

national monitoring in exchange for economic

incentives and security assurances.

15

“Military First” Politics

North Korea’s “Military First,” or Songun, philosophy established the military as the most

important North Korean institution and a means to solve social, economic, and political

problems.

16,17

Although some North Korean accounts date its origins to the 1930s, when Kim

Il Sung led an anti-Japanese guerrilla movement, Songun was not formally introduced until

after Kim Il Sung’s death in 1994. Kim Jong Il established the ideology in part because the

military served as a better power base for him than the Korean Workers' Party did.

18

Mili-

tary First has resulted in a larger role for the KPA in social and economic projects, includ-

ing large-scale infrastructure development and agriculture.

19

Although the ideology persists,

Kim Jong Un has reinvigorated the status of the Korean Workers' Party during his rule.

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

5

By the mid-2000s, Kim Jong Il had decided

to put the North on a path to a nuclear

breakout. His primary motivations were

apprehension about U.S. military inten-

tions after the 9/11 attacks and major oper-

ations in Afghanistan and Iraq, a continu-

ally worsening military imbalance on the

peninsula, and failure to obtain anticipated

energy assistance and other economic con-

cessions from international negotiations. In

2006, he resumed ballistic missile testing,

renewed satellite launch attempts using

larger multistage rockets, and carried out

North Korea’s first nuclear test.

20

Addi-

tional ballistic missile flight tests and a

second nuclear test followed in 2009.

21

Since

then, despite intense international pres-

sure and daunting technological challenges,

North Korea has unambiguously linked its

national security strategy, interests, and

identity to becoming a nuclear power with

intercontinental reach. These concepts are

now enshrined in North Korea's law, doc-

trine, and constitution.

22

Kim Jong Un has rapidly accelerated development of nuclear weapons and long-range ballistic missiles since

assuming power in 2011.

Image Source: KCNA VIA KNS/AFP

6

Kim Jong Il died in 2011. His youngest son,

Kim Jong Un, succeeded to leadership at age

27 and accelerated the pace of development of

both nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles.

By mid-2017, the new leader had overseen four

underground nuclear tests (for a total of six

since 2006) with higher yields than previous

tests and had debuted and ight-tested more

than half a dozen new ballistic missiles of vary-

ing ranges, including a submarine-launched

ballistic missile, two types of mobile intermedi-

ate-range ballistic missiles, and the rst tested

North Korean intercontinental ballistic mis-

siles capable of reaching the United States.

23,24,25

Kim Jong Un has also focused his attention

on the KPA’s conventional capabilities. From

2011-2017 Kim kept up a steady pace of pub-

lic engagements with military units to empha-

size the KPA’s centrality to the North Korean

regime, and has directed improvements in the

realism and complexity of military training. To

that end, Kim presided over high-prole artillery

repower exercises, Air Force pilot competitions,

and special forces raid training on mock-ups of

the South Korean presidential residence.

26, 27

In April 2018, Kim began prioritizing dip-

lomatic engagement likely in an effort to

encourage sanctions relief. At the same time,

North Korea introduced new weapons sys-

tems in a September 2018 military parade

featuring conventional forces.

During the rst half of 2019, Kim gradually

resumed efforts to highlight military capabil-

ities, likely signaling his frustration over the

lack of progress on diplomatic initiatives. He has

resumed publicizing military visits and weapons

launches, and in October 2020 and January 2021

military parades displayed multiple new mis-

siles, including a larger ICBM.

Since Kim Jong Un took power, North Korea

has introduced a few new conventional sys-

tems and equipment sets across all its military

services, including new tanks, artillery rock-

ets, and unmanned aerial vehicles, most of

which have been displayed in military parades

linked to important North Korean holidays

and observances.

28

The extent to which some

new equipment has been integrated into the

force is unclear, but these observations suggest

a continuing KPA emphasis on modernizing

strike weaponry, improving surveillance and

reconnaissance capabilities, and broadening

the regime’s options for raids or other special

forces operations in South Korea.

The North Korean military, once considered a

threat that would be conned to the 20th cen-

tury, has never abandoned its ambition of domi-

nating the peninsula and, if possible, reunifying

it under Pyongyang’s rule. The KPA currently

lacks the operational capability to forcibly

reunify the Korean Peninsula, as attempted in

1950, but Kim’s forces are developing capabil-

ities that will provide a wider range of asym-

metric options to menace and deter his regional

adversaries, quickly escalate any conict off the

peninsula, and severely complicate the environ-

ment for military operations in the region.

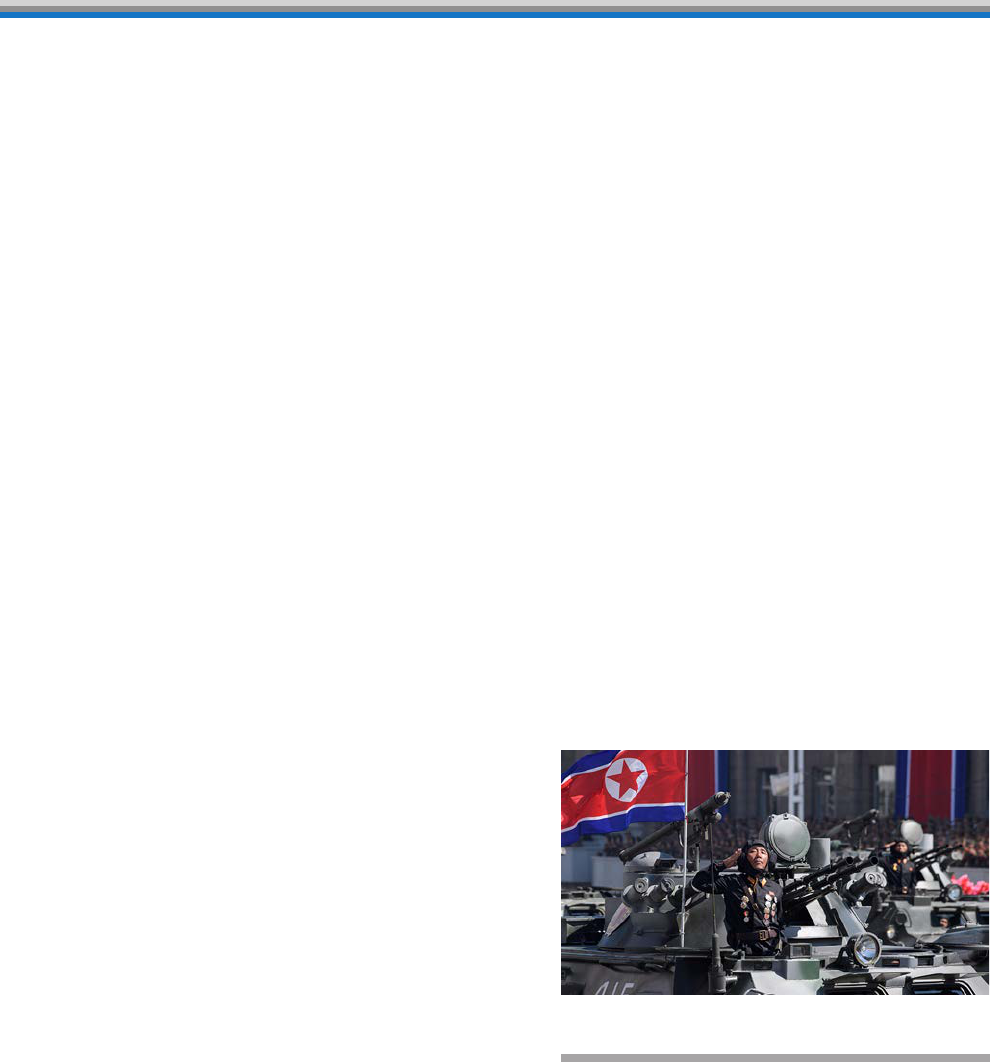

North Korean soldiers stand atop armored vehicles

during September 2018 military parade.

Image Source: AFP

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

7

The Korean People’s Army at a Glance

Services: Ground Forces, Air Force, Navy, Special Operations, Strategic Force (ballistic missiles)

Personnel: Over 1.3 million (plus approximately 7 million paramilitary, reservists and body-

guard command personnel)

Recruit base: Universal conscription

Equipment prole: Primarily Soviet-era systems; some newer systems in each service

Core strength: Massed artillery threat to South Korea, Special Operations, underground

facilities, defensive fortications

Developing strengths: Strategic ballistic missiles and nuclear weapons

Key vulnerabilities: Logistics for sustained combat operations

National Military Overview

North Korean military event in Pyongyang. The North remains one of the world’s most militarized societies.

Image Source: AFP

8

Threat Perceptions

North Korea's perception that the outside world

is inherently hostile drives the North's security

strategy and pursuit of specic military develop-

ments. This perception is informed by a history

of invasion and subjugation by stronger powers

stretching back centuries and, in the 20th cen-

tury, by the 1910–45 Japanese occupation and

the externally enforced division of the Korean

Peninsula at the end of World War II.

29

The Kim

family dynasty has exploited this history to craft

a totalitarian political culture that is dened by

resistance to outside powers and that invests

the Kim family with unique, unquestionable

authority to protect the Korean people from

external threats. To respond to this existential

threat, North Korea’s leaders believe they must

develop the military capabilities to hold exter-

nal aggressors at bay and preserve the North’s

sovereignty and independence. These essential

themes have been constant across all three Kim

dynasty leaders, with the North’s capabilities

evolving over time to meet different manifesta-

tions of the perceived threat.

The North views the United States as its primary

and immediate external security threat. This per-

ception is strongly rooted in the U.S. role during

the Korean War, the U.S. military presence on the

peninsula since the armistice, and the leading role

Washington has played in attempting to modify

Pyongyang’s behavior and constrain its nuclear

ambitions. South Korea and Japan are treated

as extensions of U.S. aggression. The North also

perceives a strong and longer-term ideological

threat from South Korea because Seoul’s different

economic and political systems represent an alter-

native—and, to Pyongyang, unacceptable—way

of life for the historically unied Korean people.

Advances in South Korean and Japanese military

capabilities over the last two decades have also

claried a major and growing gap between the

North's military power and that of its neighbors.

China and Russia have historically been allies,

partners, and patrons of the North Korean

state, but, despite broader diplomatic out-

reach since 2018, Pyongyang tends to show

little trust in either country. The North fears

absorption or preemption by a much more pow-

erful China and probably wants to preserve its

political independence from Beijing even at the

risk of alienating Chinese leadership. Pyong-

yang probably sees Russia as a relatively less

important partner in the region.

The Kim regime is driven by fears of threats to

its power from internal sources as well. Kim Il

Sung endured a period of factionalism before

consolidating absolute rule over the North in

the late 1950s; this experience taught him to

place a priority on eradicating all political, eco-

nomic, and social inuences that might threaten

his ideological control of the population. Over

decades, this manifested as a series of overlap-

ping internal security measures and societal

controls designed to ensure absolute loyalty to

the leader. Political control over the military

was particularly critical, and it remains a major

priority for the Kim Jong Un regime.

30

One of the greatest perceived threats to North

Korea’s ideological control and internal stabil-

ity is the growing inuence of what the regime

sees as politically corrosive outside information,

including through foreign media exposure and

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

9

the importing of entertainment programming

that depicts daily life in South Korea.

31

This

trend has grown as the regime’s capability to pro-

vide basic goods and services to the population

in the provinces outside Pyongyang has steeply

declined, driving an increase in market activity

that has coincided with broader availability of

cell phones. Since the 2000s, North Korea has

attempted various military and security efforts

to monitor and deal with unsanctioned activity

but has been forced to accept a degree of risk

posed by the inux of outside media.

32

National Security Strategy

North Korea’s national security strategy has

two main objectives: ensure the Kim regime’s

long-term security, which the leadership denes

as North Korea remaining a sovereign, inde-

pendent country ruled by the Kim family, and

retaining the capability to exercise dominant

inuence over the Korean Peninsula. Since the

mid-2000s, the North’s strategy to achieve these

goals has been to prioritize the development of

nuclear weapons and ballistic missiles to deliver

nuclear weapons to increasingly distant ranges

while maintaining a conventional military capa-

ble of inicting enormous damage on South

Korea. Kim Jong Un expanded the nuclear and

missile programs in an effort to develop a sur-

vivable nuclear weapon delivery capability that

the regime could use, in theory, to respond to any

external attack. Pyongyang’s goal is to maintain

a credible nuclear capability, which it believes

will deter any external attack. It also seeks to

use its nuclear and conventional military capa-

bilities to compel South Korea and the United

States into policy decisions that are benecial to

North Korea. As part of his strategy, Kim Jong

Un has publicly emphasized the ability of North

Korean nuclear-armed ballistic missiles to strike

the United States and regional U.S. allies in an

attempt to intimidate international audiences.

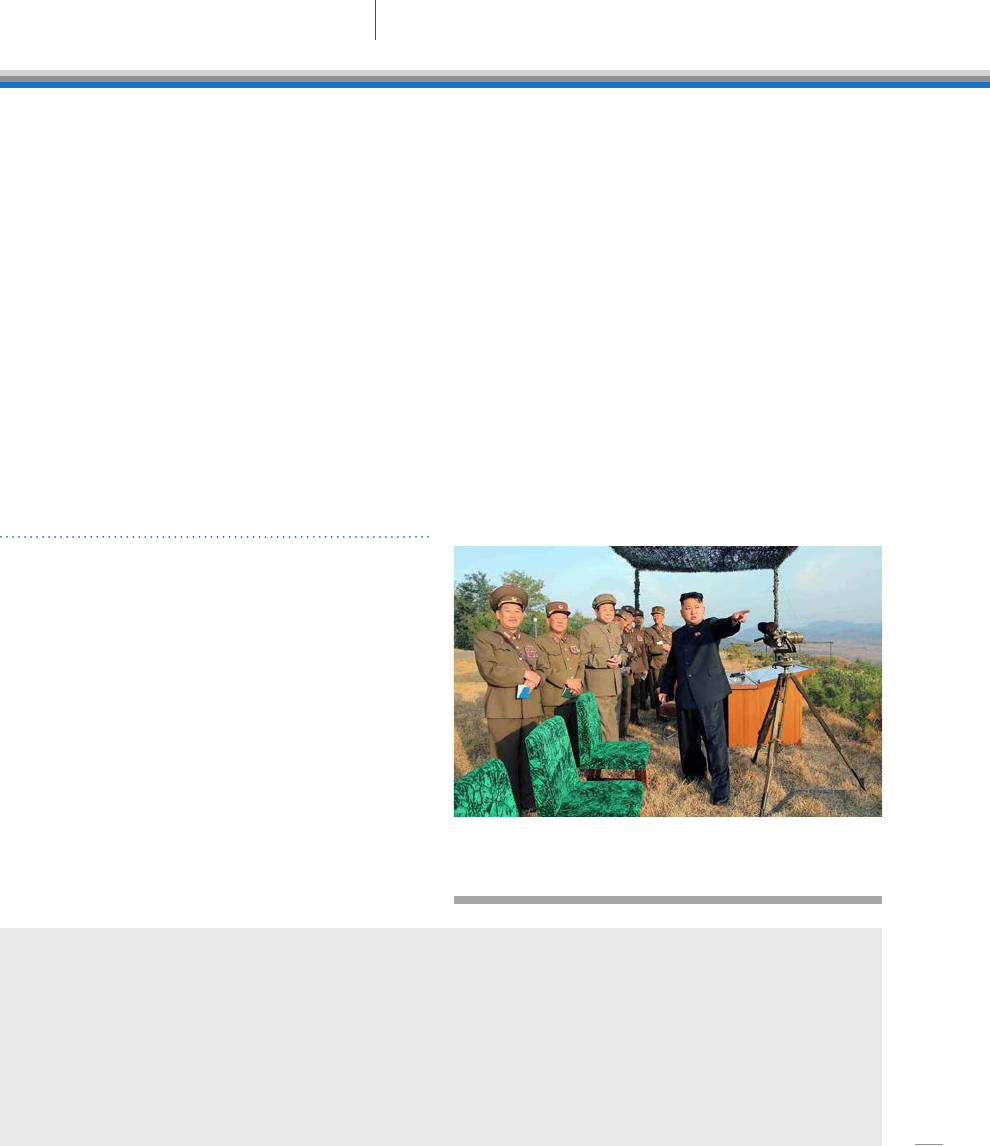

Kim Jong Un takes personal interest in developing

KPA capabilities and is often portrayed in state media

directing exercises and observing training.

Image Source: AFP/KCNA VIA KNS

From North Korean Leader Kim Jong Un's Remarks at 5th Party Plenary

Session, Released 1 January 2020

“This is a great victory… strategic weapon systems planned by the party are coming into our

grasp one by one… Such leaps in cutting-edge national defense science make our military and

technological advantage irreversible, accelerate the increase of our national strengths to the max-

imum, heighten our ability to control surrounding political situations, and give our enemies an

immense and overwhelming strike of anxiety and fear.”

33

10

The North also has traditionally used periodic,

limited-scope military actions to pressure South

Korea and to underscore the fragility of the armi-

stice, which it seeks to replace with a peace treaty

on its terms. During the 1960s and 1970s, these

actions took the form of aggressive skirmishes

along the DMZ and overt attempts to assassi-

nate South Korean leaders, including the South

Korean president, with special forces raids and

terrorist tactics.

34

In recent years the North has

conned aggression against the South to targeted

engagements in the disputed Northwest Islands

area. Confrontations between patrol craft and

other incidents along the Northern Limit Line

have claimed more than 50 South Korean lives

since 1999.

35

In 2010, North Korea attacked and

sank a South Korean corvette, the Cheonan, kill-

ing 46 sailors, and bombarded a South Korean

Marine Corps installation on Yeonpyeong Island,

resulting in 2 military and 2 civilian deaths.

36,37

No comparable attack on the South has yet

occurred under Kim Jong Un’s rule, but North

Korea’s willingness to strike South Korea with

lethal force endures. In August 2015 a land-

mine detonated in the DMZ and wounded two

South Korean soldiers, kicking off a monthlong

Targeting U.S. Forces

Historically, North Korea used military action against both South Korean and U.S. targets

after the 1953 Armistice Agreement halted the Korean War. Pyongyang targeted U.S. forces

in several high-prole incidents, including the seizure of the USS Pueblo in international

waters in 1968 and the shootdown of a U.S. reconnaissance plane in international airspace

in 1969. Pyongyang has largely avoided the deliberate targeting of U.S. personnel since the

late 1970s and has concentrated its limited-objective attacks on South Korean personnel,

except in a 1994 incident when a U.S. Army helicopter was shot down, killing one crewmem-

ber, after it accidentally strayed into North Korean airspace.

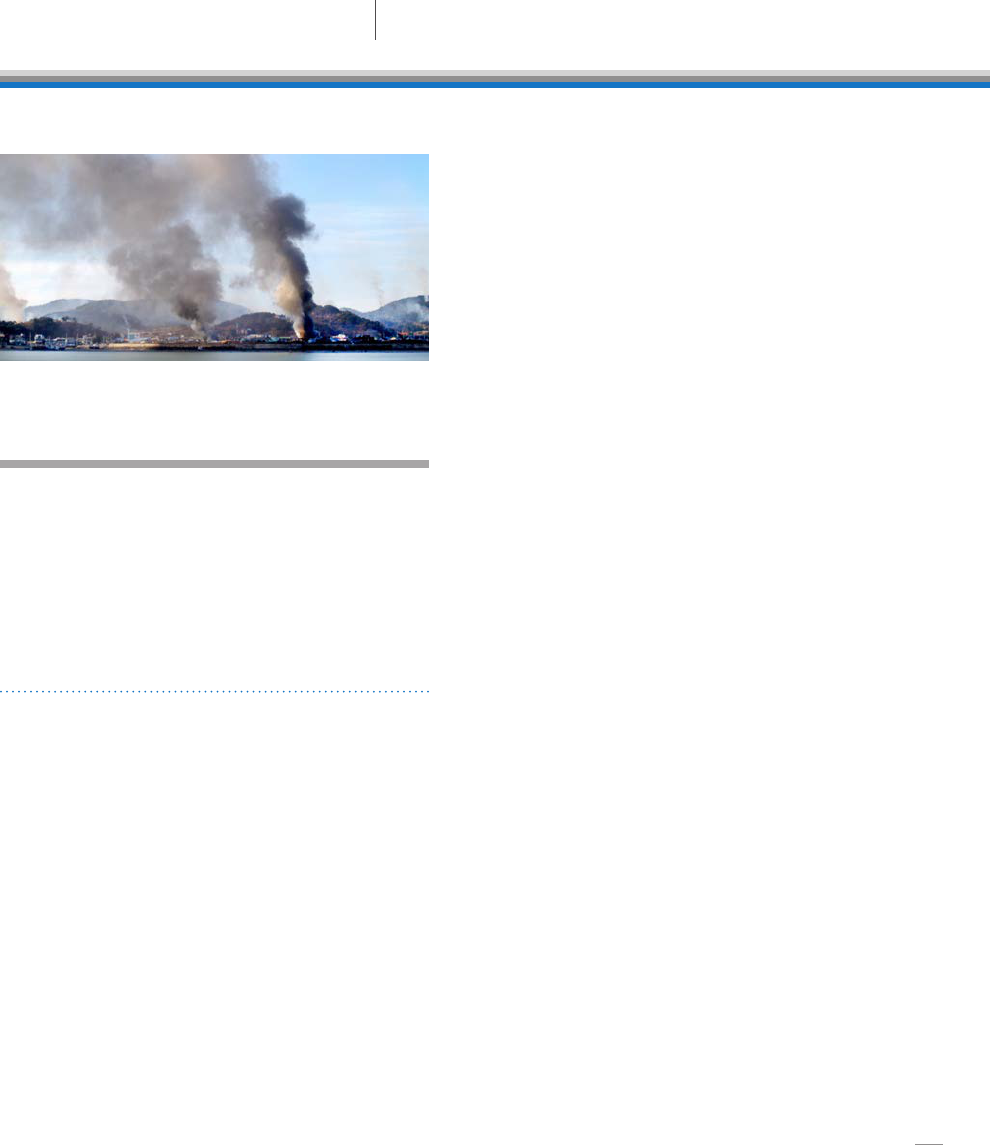

South Korean corvette Cheonan, which was sunk

by a North Korean torpedo in March 2010, pictured

here on a salvage barge.

Image Source: AFP

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

11

confrontation with the South that ultimately led

to artillery re along the border. Escalation to a

wider conict was possible although averted in

this instance.

38

Political Stability

Kim Jong Un views political stability as essential

to safeguarding his rule, a perception inherited

from his father and grandfather. No North Korean

leader has tolerated the emergence of a competing

political system or a lack of loyalty among regime

elites. To maintain stability and control, the state

retains a pervasive internal security apparatus

consisting of multiple agencies and departments

with overlapping areas of responsibility and

broad powers to monitor all North Korean citizens

for criminal and subversive behavior. North Kore-

ans are also encouraged to report on one another

at the local level through a “neighborhood watch”

system called inminban. Citizens found to have

transgressed can be interned in a massive system

of state-run prison camps, where they are sub-

jected to abusive conditions.

39

Kim has used purges and executions to eliminate

perceived threats to his authority and compel loy-

alty from subordinates. His perception of a threat

may be driven in part by sensitivity to questions

about whether the young Kim was capable of

taking full leadership of North Korea after his

father’s death, and it also seems intended to

invoke memories of Kim Il Sung, whose image

and methods Kim Jong Un has sought to emu-

late. Most prominently, Kim publicly removed

his uncle, Chang Song-taek, from the position of

vice chairman of the National Defense Commis-

sion in December 2013 and had him executed for

alleged crimes against the state.

40

In the military,

Kim has repeatedly reshufed personnel in key

defense positions and demoted senior ofcers in

rank. The result is a system that appears largely

stable from the outside, with elites motivated by

fear and co-opted with privilege to preserve the

Kim regime.

41

Despite renewed emphasis on ideological indoc-

trination and strengthened border controls,

North Koreans continue to defect abroad. Most

escape into China and, if they are able to elude

authorities and nd work, eventually make their

way to South Korea by way of Southeast Asia.

42

In 2020, 229 North Korean defectors arrived in

South Korea, a notable drop from 1,047 in 2019,

which is probably because North Korea closed its

borders to prevent COVID-19 transmission. The

defection rate has declined from a high of 2,914

people in 2009, probably owing to strengthened

security along the North Korea-China border.

43

A small number of higher-prole North Koreans

defect—notably, in 2016, including the deputy

chief of mission to the embassy in London—but

In 2010, North Korea bombarded Yeonpyeong Island

along the northwestern maritime border with South

Korea, the first kinetic strike on South Korean–occu-

pied territory in decades.

Image Source: AFP

12

this trend does not yet seem to have broadened to

the point where Kim considers it a major threat.

44

External Relations

North Korea’s external relationships do not appear

to signicantly contribute to its defense establish-

ment or boost military readiness. International

sanctions against North Korea contribute to poten-

tial partners’ lack of interest in expanding ties.

In the rst years of his rule, Kim Jong Un made

few efforts to engage foreign counterparts. How-

ever, starting in 2018 he began an international

outreach effort, travelling abroad for the rst

time as leader of North Korea to meet the lead-

ers of China, South Korea, the United States,

and Russia. He likely believes these efforts are

necessary to obtain sanctions relief.

Pyongyang’s only formal defense agreement is

with China: the 1961 Sino–North Korean Treaty of

Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance.

This agreement obliges each signatory to render

military assistance in defense of the other if one is

attacked,

45

but direct military-to-military engage-

ment between Pyongyang and Beijing has been

suspended for years. Diplomatic relations between

both countries worsened after North Korea’s

nuclear and missile tests accelerated. In 2017,

China instituted new import restrictions intended

to affect the North Korean economy and contin-

ued to call for North Korea to cease its nuclear

and ballistic missile test activities. Kim Jong Un

visited China and met with President Xi Jinping

in March, May, and June of 2018, and in January

2019, indicating a desire to nurture relations. Xi

made his rst visit to North Korea in June 2019.

46

Russia, which provided substantial military

assistance and equipment to North Korea during

the Soviet era, has largely curtailed its defense

relationship with North Korea. Since UNSC

sanctions in August 2017, however, some eco-

nomic and diplomatic engagement with Russia

has taken place. In October 2017, a state-owned

Russian company began to provide a second inter-

net connection to North Korea, reducing Pyong-

yang’s dependence on China.

47

Kim Jong Un met

with Russian President Vladimir Putin for the

rst time in April 2019 as part of Kim’s effort to

diversify diplomatic and economic ties and fur-

ther reduce economic dependence on China. The

two discussed diplomatic and commercial oppor-

tunities, although no ofcial agreements were

announced.

48

Thus far, these overtures have

led to minimal improvements in relations given

North Korea’s perception of Russia’s pressure to

denuclearize and failure to provide signicant

economic and military concessions.

North Korea views Japan and South Korea as

adversaries but maintains lines of communi-

cation with both countries. North Korea met

with a Japanese delegation in 2016 to discuss

Kim Jong Un meets with Chinese President Xi Jinping

in Beijing on 8 January 2019.

Image Source: AFP PHOTO/KCNA VIA KNS

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

13

an ongoing dispute over the disposition of Japa-

nese nationals abducted by North Korea during

the late 1970s and early 1980s. The North and

South held two summits in 2018, and have inter-

mittently held high-level talks at Panmunjom

in the DMZ to tamp down tensions in inter-Ko-

rean relations. In September 2018, the Koreas

signed the Comprehensive Military Agreement,

which calls on both sides to take measures to

prevent accidental military clashes. After an

initial push to carry out the agreement, prog-

ress stalled and in June 2020 North Korea

demolished a liaison ofce and threatened to

reverse military actions taken thus far.

49,50,51

Defense Budget

Although the regime does not publish exact eco-

nomic gures, estimates are based on trends

in observed economic activity. As such, North

Korea’s economy shrank by about 4 percent

in 2018 because of UNSC sanctions. In 2019,

North Korea’s economy grew slightly, but likely

contracted in 2020 because of trade disruptions

due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

52

Coal, other

minerals, and clothing account for almost 70

percent of Pyongyang’s nonmilitary foreign

trade, according to the International Trade Cen-

tre, but are currently banned as North Korean

exports by UNSC sanctions imposed in 2017.

53

Defense spending is a regime priority. Spending

estimates range from $7 billion to $11 billion;

20–30 percent of North Korea’s GDP is allocated

to the military.

54

This level of commitment makes

North Korea the highest spending nation in the

world for defense as a percentage of GDP. Pyong-

yang has probably increased defense spending

during the past decade and likely will continue

devoting a large portion of its GDP to national

defense through at least 2021.

55

A detailed

breakdown of North Korean military spending

by categories such as personnel, procurement,

or operations and maintenance is unavailable.

Pyongyang has mustered sufcient funds, most

likely by shifting priorities, to nance foreign

procurement and domestic development and pro-

duction for testing missile systems and nuclear

weapons. Nonmonetary resources, including raw

materials and electrical power, are also priori-

tized for use in military projects.

56

National Defense Burden Comparison, 2020 Global Baseline

1707-13888

<1% <1-1.9% 2-9.9% 10-19.9% 20-30 %

NORTH

KOREA

Percentage of GDP Spent on Defense Number of Countries

#

63

61

62

2

2

14

Military Doctrine and Strategy

Perceptions of Modern Conflict

North Korea understands that the character of

war has changed since its last sustained com-

bat experience in 1953 and sees its military as

largely unprepared to engage in modern war-

fare. Pyongyang probably assesses its force as

a whole cannot prevail in combat against the

United States, given U.S. forces’ overwhelm-

ing advantages in power projection, strategic

air superiority, and precision-guided stand-

off strike capability. This perception has been

informed by North Korea’s monitoring of U.S.

operations in the 1991 Gulf War, the 1999

Kosovo air campaign, campaigns in Afghan-

istan and Iraq, and U.S.-led air operations in

Libya in 2011 and Syria since 2014. The North

also is a keen observer of South Korean military

capabilities and probably judges it is at a qual-

itative disadvantage against its neighbor.

57,58,59

North Korean defense planning, therefore, has

adapted to deter direct U.S. military interven-

tion by signaling that the cost of such interven-

tion would be unacceptably high to the United

States even if North Korea ultimately lost the

engagement. In the last few years, this effort

to shape adversary deterrence calculations has

centered on developing and publicizing a sur-

vivable nuclear-armed ballistic missile force.

Should deterrence fail, North Korea would

seek to maximize its defensive advantages—

including inhospitable terrain, widespread

use of underground facilities, and a population

conditioned from birth to resist foreign invad-

ers—to raise the cost of taking and holding

North Korean territory.

Some investments in specic North Korean

military capabilities are intended to improve

the odds of North Korean success in a mod-

ern conict. However, these efforts are gener-

ally isolated to a few areas and would not, in

Pyongyang’s estimation, confer overwhelming

advantage on the KPA in a modern conict

against the United States and South Korea.

Military and Security Leadership

Kim Jong Un is the supreme commander of

the KPA, in addition to his position as head of

all governmental, political, and security insti-

tutions in the country. He holds the rank of

marshal in the KPA and was appointed a four-

star general before his succession, although

he is not known to have any actual military

experience. In North Korea’s unitary leader-

ship structure, Kim is the ultimate authority

for all defense and national security decisions,

including operational planning and execu-

tion, procurement and acquisition, and strat-

egy and doctrine. As the rst secretary of the

Korean Workers' Party, he establishes policy

and guidance for North Korea’s military and

implements party policy through key nation-

al-level organizations.

60,61

As the party's Cen-

tral Military Commission chairman and the

State Affairs Commission chairman, Kim con-

trols all military and defense-related policy,

with broad authority to consolidate political,

military, and state powers during both war-

time and peacetime.

62

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

15

Kim Jong Un at a military parade, April 2017. Kim has directed improvements to each KPA service’s capabilities.

Image Source: AFP/KCNA VIA KNS

Kim Jong Un's Leadership Priorities

Born in 1983, Kim Jong Un was the youngest of Kim Jong Il’s three sons. Kim Jong Il formally

introduced Kim Jong Un as his successor in 2009, bypassing his older sons, Kim Jong Nam and

Kim Jong Chol. Little is known about Kim’s life before his succession to leadership in 2011.

Kim’s priorities as leader of North Korea have been to solidify the state's nuclear capability and

make rapid strides toward achieving a ballistic missile arsenal capable of threatening the United

States while attempting to modernize the economy – a “dual line” policy called Byungjin in the

North. Although economic development is a priority, Kim is willing to endure nancial losses in

order to advance other goals; North Korean nuclear and missile tests continue to result in UN

sanctions, and, in 2016, a rocket launch prompted South Korea to close the Kaesong Industrial

Complex, which provided the regime about $100 million a year through cash remittances.

In relations with the United States, Kim initially responded to Washington’s demands that he

abandon his nuclear aspirations by accelerating the program’s development and by issuing spe-

cic threats to attack the United States. In 2018, Kim demonstrated a willingness to participate

in talks on denuclearization. However, since 2019 he has demonstrated his intent to continue bol-

stering North Korea’s military deterrent by developing and testing new missiles and developing

new military equipment for the conventional force.

16

Through the General Political Bureau, North

Korea maintains a separate political command

and control apparatus to ensure military loy-

alty to the Kim regime and implementation of

party guidance. The bureau leads all political

and ideological training, monitors morale and

personal lives, guides servicemen’s political

lives, and disseminates propaganda for the

military in order to maintain military loyalty

to the regime. The director of the General Polit-

ical Bureau usually serves as a key adviser to

Kim Jong Un.

Vice Marshall Kwon Yong-chin

was appointed head of the General Political

Bureau in January 2021.

63,64,65

Operational control of North Korea’s armed

forces resides in the General Staff Department,

which reports directly to Kim Jong Un.

66

The

department as a whole aggregates and opera-

tionally commands all military service head-

quarters, functional and combat commands,

and military communications, and it evaluates

the overall training and readiness of the North

Korean military. Vice Marshal Pak Chong-chon

was appointed as the General Staff Department

head in September 2019, and is one of Kim’s

principal military advisers.

67

The Ministry of National Defense (MND) is

responsible for administrative control of the

military and external relations with foreign

militaries. MND manages the manpower and

resource needs of North Korea’s conventional

armed forces and special operations forces.

In the past MND-controlled companies were

involved in earning foreign currency through

exports and domestic distribution, though this

activity has probably been reduced by interna-

tional sanctions.

68

As of July 2021, Colonel Gen-

eral Kim Chong-kwan has been removed from

his position as MND chief and his replacement

was not announced. The MND minister is posi-

tioned primarily to manage defense acquisi-

tions, resourcing and nancing allocations for

all North Korean armed forces.

69

General Staff Department Chief Vice Marshal Pak

Chong-chon with Kim Jong Un.

Image Source: Rodong Sinmun

Vice Marshall Kwon Yong-chin, General Political Bureau .

Image Source: Uriminjokkkiri

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

17

National Military Command

and Control

As the KPA supreme commander and central

decisionmaker in North Korea, Kim Jong Un

is the linchpin of KPA command and control.

Kim exercises command and control over all

corps-level military organizations, includ-

ing ground, air, naval, and ballistic missile

forces.

70

The General Staff Department main-

tains overall control of all North Korean mil-

itary forces and is charged with turning the

supreme commander’s directives into opera-

tional military orders.

71

North Korean Military Command and Control

1707-13888

Supreme Commander Kim Jong Un operates as the absolute decisionmaker of North Korea’s armed

forces. The Supreme Command would disseminate any order from Kim to North Korea’s armed

forces, including its ballistic missile corps, the Strategic Force. As the Korean Workers’ Party Cen-

tral Military Commission (CMC) chairman and the State Affairs Commission (SAC) chairman, Kim

controls all military and defense-related policy.

Supreme Commander Kim Jong Un

Korean Workers’ Party

Central Military Commission

Ministry of National Defense

Supreme Command

General Staff Department

State Affairs Commission

Ground Forces Air Force Navy Strategic Force

Wartime Procedure

Peacetime Consultation

18

During wartime, Kim Jong Un would exercise

overall control of preparations, mobilization, and

operations. The Supreme Command functions as

both the highest ranking advisory board to Kim

on all state and military affairs and as the organi-

zation charged with converting the supreme com-

mander’s strategies into actual wartime direc-

tives. The Supreme Command would comprise

senior ofcers from the General Staff Depart-

ment, Ministry of National Defense, and other

key national-level organizations.

72

Nuclear Command and Control

Kim Jong Un has established through public

policy statements and legislation that he is the

sole release authority for North Korean nuclear

weapons use against any adversary. In 2013,

North Korea revised its national constitution

and passed a law on nuclear use, which stated

that nuclear weapons could not be used with-

out an express order from the supreme com-

mander.

73

Kim has personally authorized North

Korea's nuclear tests, most recently in Septem-

ber 2017. North Korean state-sponsored media

published the order with his signature after

the test occurred.

74

Other North Korean public

media releases have emphasized Kim’s singular

role in authorizing missile force alerts and the

signing of a “repower strike plan,” ostensibly

for nuclear attack on the United States.

75

Kim Jong Un exercises personal command and control over North Korea’s nuclear, ballistic missile, and conven-

tional military forces. In this 2013 image released by North Korean state media, a map of notional missile strikes

on the United States is the backdrop to Kim signing a “firepower strike plan.”

Image Source: AFP

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

19

Core North Korean Military Capabilities

Nuclear Weapons and Ballistic Missiles

orth Korea has aspired to become a

nuclear weapons power for decades.

Although the nuclear program’s foun-

dation dates to the 1950s, Pyongyang started

making its most signicant progress toward

developing a nuclear weapons capability after

withdrawing from the Treaty on the Nonprolifer-

ation of Nuclear Weapons in 2002, citing increas-

ing alarm over U.S. military activities abroad

and dissatisfaction with the pace at which inter-

national economic aid, promised in past nuclear

negotiations, was arriving. The North began

testing nuclear devices underground in 2006.

North Korea discloses very few details about its

nuclear weapons inventory and force structure.

Program History and Pathway to

Weapon Development

North Korean nuclear research began in the

late 1950s through cooperation agreements

with the Soviet Union. The North’s rst

research reactor began operating in 1967,

and Pyongyang later built a nuclear reactor

at Yongbyon with an electrical power rating

of 5 megawatts electrical (MWe). This reactor

began operating in 1986 and was capable of

producing about 6 kilograms of plutonium per

year. Later that year, high-explosives testing

and a reprocessing plant to separate plutonium

from the reactor’s spent fuel were detected.

Construction of additional reactors—a 50-MWe

reactor at Yongbyon and a 200-MWe reactor at

Taechon—provided additional indications of a

larger-scale nuclear program.

76

North Korea joined the Nonproliferation

Treaty in 1985, but inspections only started

7 years later under the treaty's safeguards

regime, inviting questions about the North’s

N

Reactor at the Yongbyon Nuclear Research Complex.

North Korea has acknowledged both plutonium

reprocessing and uranium enrichment activities at

this installation. Activities at Yongbyon sites continue.

Image Source: Wikimedia Commons

20

North Korean Nuclear and Rocket Launch Facilities

1707-13887

North Korea’s launch installations have supported

ground test and launches of multi-stage rockets,

nominally for putting satellites in orbit. These ac-

tivities provided a test bed for long-range ballistic

missile technology, and support the development

of ICBMs now in the North Korean inventory. Recent

activities at the Pyongsan Uranium Concentration

Plant have also been reported.

77

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

21

plutonium production. In 1994, North Korea

pledged to freeze and eventually dismantle its

plutonium programs under the Agreed Frame-

work with the United States. At that time, a

number of sources estimated that Pyongyang

had separated enough plutonium for one or two

nuclear weapons. North Korea allowed the Inter-

national Atomic Energy Agency to place seals

on spent fuel from the Yongbyon reactor and to

undertake remote monitoring and onsite inspec-

tions at its nuclear facilities.

78

In 2002, negotiators from the United States con-

fronted North Korea with evidence of a clandes-

tine uranium enrichment program, a claim that

North Korean ofcials publicly denied. Disagree-

ment over the North’s establishment of a uranium

enrichment program led to the breakdown of the

Agreed Framework. The United States reached

agreement with members of the Korean Economic

Development Organization and stopped shipment

of heavy fuel oil to North Korea, whose response

was removing the international monitors and

seals at the Yongbyon facility and restarting its

plutonium production infrastructure.

79

North Korea has demonstrated the capability

to produce kilogram quantities of plutonium for

nuclear weapons and has claimed to possess the

ability to produce enriched uranium for nuclear

weapons. The North disclosed a uranium enrich-

ment plant to an unofcial U.S. delegation in

late 2010 and claimed it was intended to produce

enriched uranium to fuel a light-water reactor.

80

The North began underground nuclear testing in

2006 and used early tests to both validate device

designs and to send a political signal that it was

advancing its nuclear capability. By September

2017 North Korea had conducted six nuclear

tests: one each in 2006, 2009, and 2013; two in

2016; and one in September 2017, according to

seismic detections and public claims by North

Korean media.

81,82

Successive tests have demon-

strated generally higher explosive yields, accord-

ing to seismic data.

83

The September 2017 test

generated a much larger seismic signature than

had previous events, and North Korea claimed

this was a test of a “hydrogen bomb” intended

for use on an intercontinental ballistic missile

(ICBM).

84

North Korea has exclusively used the

underground nuclear test facility in the vicinity

of Punggye for its nuclear tests. In May 2018,

North Korea disabled some parts of the Punggye

test site, announcing that it no longer needed

to conduct nuclear tests. However, Pyongyang

retains a stockpile of nuclear weapons minimiz-

ing the impact of this development.

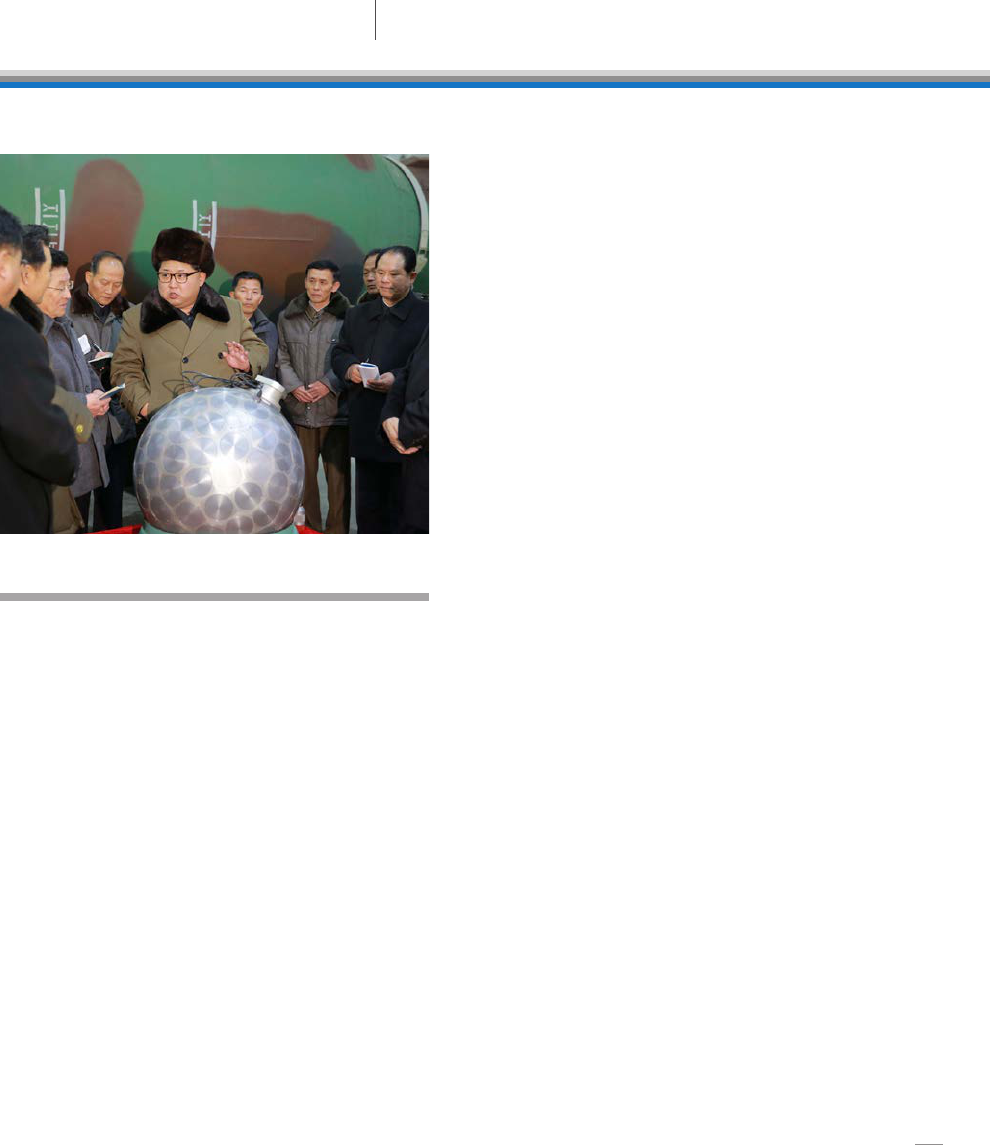

Kim Jong Un examines a mock nuclear warhead dis-

played in front of a ballistic missile.

Image Source: KCNA VIA KNS/AFP

22

Ballistic Missile Force

North Korea established a Strategic Force (pre-

viously known as the Strategic Rocket Forces)

in 2012 and has described this organization

as a nuclear-armed ballistic missile force. The

Strategic Force includes units operating short-

range (SRBM), medium-range (MRBM), inter-

mediate-range (IRBM) ballistic missiles, and

ICBMs, each of which North Korea has stated

represents a nuclear-capable system class. In

2016, the North claimed a Scud class SRBM

launch had tested nuclear weapon components

in a mock attack against a South Korean port.

85

Pyongyang has occasionally hinted at the

possibility of other nuclear-capable units, for

instance, by marching infantry troops carrying

backpacks emblazoned with the nuclear sym-

bol in a 2013 military parade.

86

The North’s ballistic missile force is structured

around multiple regional and intercontinental

target sets. The Strategic Force operates Scud

class missiles that can range South Korea, some

extended-range variants of the Scud that can

reach Japan, and the No Dong MRBM, which

can reach Japan. This force also is responsible for

the Hwasong-12 IRBM, which was designed to

range Guam; and the Hwasong-14 ICBM, capa-

ble of reaching the continental United States.

87

North Korea revealed its rst road mobile

ICBM in a 2012 military parade. In 2015, it

began ight-testing a submarine-launched bal-

listic missile (SLBM), the Pukguksong-1. Sub-

sequently, the North conducted an initial ight

of a new solid-propellant MRBM, the Pukguk-

song-2 and a new IRBM, the Hwasong-12, which

appears to be a replacement for the Musudan

IRBM. North Korea conducted multiple ight

tests of the Hwasong-12, including ight tests

in August and September 2017 over northern

Japan, ultimately reaching a range of approxi-

mately 3,700 kilometers, its longest-range direct

trajectory ballistic missile ight tests to date.

88,89

North Korea conducted an inaugural launch

of its ICBM class system, the Hwasong-14 on

4 July 2017 and again on 28 July 2017. It then

launched a second type of ICBM, the larger

Hwasong-15 on 28 November 2017.

90

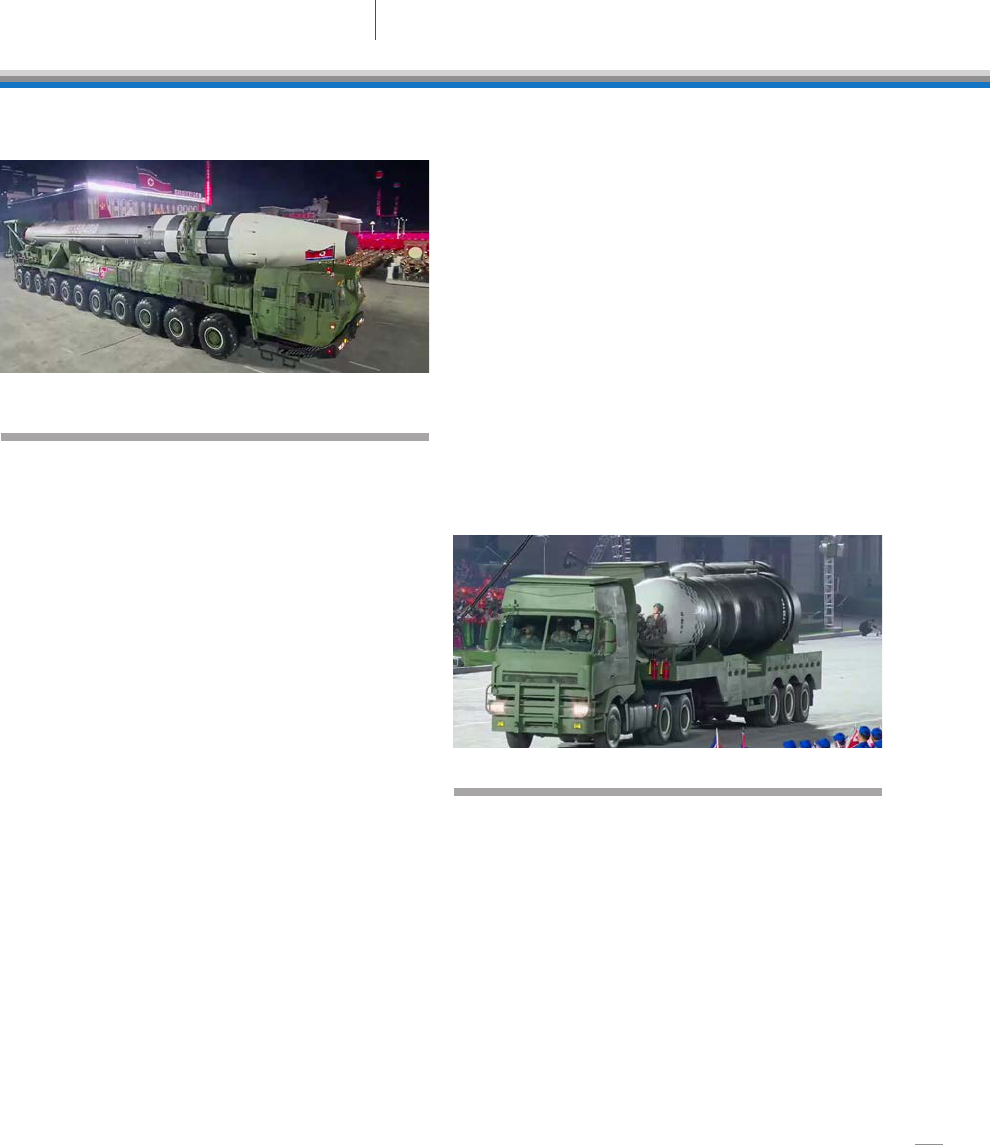

Hwasong-14 ICBM on a road-mobile transporter-erec-

tor-launcher prior to launch, July 2017.

Image Source: KCNA VIA KNS/AFP

Hwasong-15 ICBM on its mobile launcher, November 2017.

Image Source: KCNA VIA KNS/AFP

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

23

North Korea conducted this second Hwasong-14 ICBM

flight test on 28 July 2017.

Image Source: KCNA VIA KNS/AFP

A TD-2/Unha-3 space launch vehicle preparing for

launch, April 2012. Satellite launches contribute valu-

able data to the ballistic missile program.

Image Source: AFP

During an April 2017 parade, North Korea

showcased a modied ICBM launcher with

a launch canister, as well as a new mobile-

erector-launcher with a launch canister.

Road-mobile launch canisters are typically

associated with solid-propellant missiles.

Actual missiles for the launch canisters were

not displayed. The North also paraded a

new Scud variant with a modied warhead,

probably a maneuverable reentry vehicle.

91

North Korea’s February 2018 military parade

included one new short-range ballistic mis-

sile, which was arrayed in pairs on four-axle

trucks. North Korea began testing a version

of this solid-propellant missile in May 2019.

92

Between 2019-2021, North Korea launched a

total of four new types of SRBMs.

North Korea also possesses space launch vehi-

cles (SLV) which could reach the continental

United States if congured as ICBMs.

93

These

systems use ballistic missile technology, and

24

Ballistic Missile Inventory

96

1707-13888

Systems

Number of

Launchers

Propellant

Deployment

Mode

Maximum

Range (km)

SCUD B/C (SRBM) Fewer than 100 Liquid Road-Mobile 300–500

SCUD ER (SRBM) Undetermined Liquid Road-Mobile 1,000

Unnamed SRBM variants

(Launched 2019)

Undetermined Solid Road-Mobile 380–600+

No Dong (MRBM) Fewer than 100 Liquid Road-Mobile 1,200+

Hwasong-10

(Musudan IRBM)

Fewer than 50 Liquid Road-Mobile 3,000+

Hwasong-12 (IRBM) Undetermined Liquid Road-Mobile 4,500

Pukguksong-1 (SLBM)

At least 1

submarine

Solid Submarine 1,000+

Pukguksong-3 (SLBM) Undetermined Solid Submarine 1,000+

Pukguksong-4 (SLBM) Undetermined Solid Submarine Unknown

Pukguksong-5 (SLBM) Undetermined Solid Submarine Unknown

Pukguksong-2 (MRBM) Undetermined Solid Road-Mobile 1,000

Hwasong-14 (ICBM) Undetermined Liquid Road-Mobile 10,000+

Hwasong-15 (ICBM) Undetermined Liquid Road-Mobile 12,000+

Unnamed ICBM

(Paraded 2015)

Undetermined Liquid Road-Mobile Intercontinental

Unnamed Larger ICBM

(Paraded In 2020)

Undetermined Liquid Road-Mobile Intercontinental

- Hwasong and Pukguksong designators are based on published North Korean names.

- All ranges are approximate.

space launches provide North Korea with valu-

able data applicable to the development of long-

range, multi-stage ballistic missiles.

94

North

Korea’s Taepo Dong 2 (TD-2), called Unha-3 in

the North, has been under development since at

least the early 2000s. Its rst ight test attempt,

in 2006, failed; subsequent launches in 2009 and

April 2012 also failed. In December 2012 and

February 2016, the North successfully launched

an object into low Earth orbit with the TD-2.

95

The 4 July 2017 Hwasong-14 launch was North

Korea’s rst ICBM ight test. The Hwasong-14

was launched almost straight up to an unusu-

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

25

ally high altitude of approximately 2,800 kilo-

meters above the Earth before impacting into

the Sea of Japan.

97

On 28 July, North Korea

tested the Hwasong-14 to an even higher loft

than achieved on 4 July. The lofted-launch

technique enables the North to model how

far the missile could travel without overying

another country and without a full-range ight

test. In its tested conguration the Hwasong-14

ICBM is capable of reaching North America if

own on a direct trajectory based on the ver-

tical distance traveled by the missiles during

the July 2017 ight tests.

98

North Korea ight

tested another new ICBM – identied as the

Hwasong-15 - in a lofted trajectory at an apo-

gee of 4,475 kilometers on 28 November 2017.

These ICBM ight tests mark signicant mile-

stones in North Korea’s ballistic missile devel-

opment process—the rst ight tests of mis-

siles which can reach the United States.

99,100

North Korea's ICBM Flight-test Trajectories, 2017

1707-13887

By testing ICBMs to

extremely high altitudes,

North Korea can assess

how they would perform

at long distances while

keeping impact areas

within the region.

26

Nuclear Deterrence Strategy and Use Doctrine

The steady development of road-mobile ICBMs, IRBMs, and SLBMs highlights Pyongyang’s

intention to build a survivable, reliable nuclear delivery capability.

101

This developing capa-

bility has been accompanied by high-level statements, the rst of which was issued in 2013,

in which North Korea stated it would use nuclear weapons to respond to an invasion and

may use them to prevent an attack. Together, these developments suggest the potential

for nuclear weapons to be used at any stage of conict when the North believes itself in

regime-ending danger.

102,103,104

The point at which North Korean leadership would perceive

this threat is unclear, as are specic regime plans for nuclear use.

North Korea Missile Launches and Nuclear Tests

105

1707-13888

Accounts for full flight tests only. Does not include partial tests of missile subsystems, such as static engine firings or

cold-launch ejection tests, tests of air defense systems, close-range ballistic missiles (CRBMs), short-range rockets,

or artillery firings. Updated as of September 2021.

MRBM

(1,000–3,000 km)

SLBM

(1,000–3,000 km)

ICBM

(5,500+ km)

SRBM

(300–1,000 km)

Space Launch

Cruise Missile

Unknown Missile

Nuclear Test

IRBM

(3,000–5,500 km)

0

1984

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1998

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2012

2013

2014

201 5

2016

2017

2018

5

10

15

Number of Events

20

25

2019

2020

2021

KIM Il SUNG KIM JONG IL KIM JONG UN

1984-1994 1994-2011 2011-present

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

27

North Korean Ballistic Missile Ranges

1707-13887

28

Biological and

Chemical Weapons

North Korea has a longstanding biological

warfare (BW) capability; additionally its bio-

technology infrastructure could be redirected

to support a BW program.

106

The North is a

signatory to the Biological and Toxins Weap-

ons Convention (BWC) but has yet to declare

any relevant developments and has failed to

provide a BWC condence-building measure

declaration since 1990.

107,108,109

Pyongyang may

consider the use of biological weapons during

wartime or as a clandestine attack option.

North Korea has a chemical warfare (CW) pro-

gram that could comprise up to several thou-

sand metric tons of chemical warfare agents,

and the capability to produce nerve, blister,

blood, and choking agents.

110

North Korea is

not a party to the Chemical Weapons Con-

vention. North Korea probably could employ

CW agents by modifying a variety of conven-

tional munitions, including artillery and bal-

listic missiles, along with unconventional,

targeted methods. For example, North Korea

was responsible for the assassination of Kim

Jong Un’s half-brother in Malaysia using the

nerve agent VX.

111

An Indonesian woman and

a Vietnamese woman were tried for the mur-

der; four North Koreans were charged but

ed the country before arrest.

Offensive

Conventional Systems

North Korea’s conventional military consists of

the ground, air, naval, and special operations

forces. Each is limited to operations on or around

the Korean Peninsula and poses a direct threat

to South Korea and to U.S. forces based in South

Korea. Neither the Air Force nor the Navy can

operate at long distances off-peninsula or project

power outside the region. North Korea’s conven-

tional strike capability is concentrated primarily

in massed re from KPA artillery forces, Special

Operations Forces (SOF), and, less effective,

xed-wing attack by ghters and bombers.

KPA Ground Forces operate thousands of long-

range artillery and rocket systems along the

entire length of the DMZ. These weapons include

close-range mortars, guns, and multiple rocket

launcher systems (MRLs) trained on South

Korean military forces deployed north of Seoul,

and longer-range self-propelled guns, rockets,

and CRBMs that can reach Seoul and some points

Long-range artillery guns in mass firing position for

training exercise.

Image Source: KCNA VIA KNS/AFP

NORTH KOREA MILITARY POWER

A Growing Regional and Global Threat

DEFENSE INTELLIGENCE AGENCY

29

North Korean Artillery and Rocket Threat to South Korea

1707-13887

30

south of the capital. Collectively, this capability

holds South Korean citizens and a large number

of U.S. and South Korean military installations

at risk.

112

The North could use this capability to

inict severe damage and heavy casualties on the

South with little warning.

North Korean SOF are designed for rapid offen-

sive operations, inltration, and limited attack

against vulnerable targets in South Korea.

Operating in specialized units, SOF person-

nel are among the most highly trained, well-

equipped, best-fed, and highly motivated forces

in the KPA. Recently, North Korea has empha-

sized SOF unit training with particular focus on

improving their capability to raid key govern-

ment installations in the South.

The North Korean Air Force can y strike mis-

sions against targets in South Korea with ght-

ers and bombers; its most capable platforms are

the MiG-29 Fulcrum ghter and the MiG-23

Flogger ghter, although these would have con-

siderable difculty overcoming South Korea’s

more modern air forces and air defenses. Sev-

eral North Korean unmanned aerial vehicles

(UAVs) have been sighted over South Korea

since 2014; models that crashed and were exam-

ined by the South Korean government had been

congured for surveillance and reconnaissance,

but the North could arm future UAVs.

113

National Defense

Defending the North Korean homeland against

external attack is a foundational KPA mission,

constituting a major share of effort for KPA