June 2024

Modern Languages: Spanish

I’m pleased that you have been offered a place to read Modern Languages at St Hilda’s and

I’m very much looking forward to welcoming you to College in October for what I hope will

be the first of many happy terms in Oxford.

Please find attached a note - ‘Starting Spanish at Oxford’ - explaining the structure of the first-

year course in Spanish, incorporating a reading list of texts that you’ll need to work through

before you come up in October, and offering further suggestions of possible background reading

you might like to undertake. Ideally you should acquire your own copies of the prescribed texts

(for Papers III and IV) and you should take your time over the summer to read through them

carefully, taking notes to help you learn their content (plot, characters, interesting points of style,

etc.) in advance of the start of the academic year, when a good grasp of their detail will be

necessary. Knowing these materials well will make your first term easier and more productive.

You should also, please, make lists of the vocabulary you don’t know from these texts, and you

should try to learn it.

Please do keep the receipts of your book purchases as you can apply for a College book grant

to claim back up to £60 of the cost.

If you have any questions or doubts about how to approach the above, please do just get in

touch via the College’s Academic Office.

In the meantime, I hope you have an enjoyable summer.

Yours sincerely,

Dr Roy Norton

Lecturer in Spanish

St Hilda’s College, Cowley Place, Oxford OX4 1DY www.st-hildas.ox.ac.uk

Registered Charity Number 1137537

Starting Spanish at Oxford

General

Your initial terms at Oxford can seem daunting and you should not worry if they do. Your tutors will be

on hand to support your transition to university life and they understand the (often exciting) challenges

this involves. You will need to put in a significant amount of work to achieve the standard required by

the end of the first year, but, again, your tutors will help you gauge this, and they will offer guidance

and recommend that you read particular books and works of criticism, for instance. It is worth

highlighting now, just for the avoidance of doubt, that you will have to do much of the core work

independently, and that means learning to be well organized, to use your time effectively, and to be self-

disciplined. So that you can get as much as possible out of your contact time, you must attend all

tutorials, classes and lectures (unless you have a good reason for absence, e.g., illness, medical

appointments, etc.). What follows is a series of recommendations regarding both general background

reading and the specific works of literature that you will study in your first year, along with some

suggestions for boosting your Spanish-language knowledge and skills.

Language

Grammar and Syntax

Some Spanish A-level courses do not involve much formal study of grammar and syntax, so you will

need to study these quite intensively over the coming months, learning the associated technical

terminology in both English and Spanish. The best available textbook is Butt and Benjamin’s A New

Reference Grammar of Modern Spanish (6th edition), which you should buy, ideally, as we will be using

it in many of our college language classes. Also very useful is Batchelor and Pountain’s Using Spanish:

A Guide to Contemporary Usage. More recently, our own former Spanish Instructor, Javier Muñoz-

Basols, collaborated on two books which he wrote as a direct result of teaching the Oxford course. They

are titled Speed Up Your Spanish: Strategies to Avoid Common Errors (London: Routledge, 2009) and

Developing Writing Skills in Spanish (London: Routledge, 2011). The former will be of immediate and

lasting use to you, while the latter will come into its own in your second year.

Vocabulary

You will need to build up your Spanish vocabulary quickly and extensively. There is no easy way of

doing this – you must simply look up all the new words which you encounter and note them in a

designated vocabulary book. One excellent way of going about this is by studying the Prelim Paper III

texts in minute detail. You should also make sure to read a good Spanish-language newspaper online at

least once a week. El País, Spain’s leading national daily, charges modest subscription rates and they

are often on special offer. You should read the leading articles (especially on Sundays) and, on

Saturdays, the cultural supplement ‘Babelia’, which deals with recent developments in Hispanic

literature, art, music, etc. Many leading Spanish and Spanish American writers are regular contributors.

There are also various books which will help you increase your vocabulary and learn how to use it in

appropriate contexts. The two best are probably Using Spanish Vocabulary and Using Spanish

Synonyms, both by Batchelor and published by Cambridge University Press. The former is largely topic

based, is particularly useful when it comes to distinguishing between the register of words, and includes

many examples from Latin American Spanish. Your college library should have copies of all the books

mentioned here, so you do not necessarily need to acquire your own copy (except of Butt and Benjamin),

though you may wish to.

You should also read widely and frequently in English (a good newspaper, contemporary fiction, etc.),

both because you will be required to translate from Spanish into English throughout your degree and

because it will help you write your tutorial essays. Developing the range and fluency of your English

expression will be important.

Dictionaries

There is no wholly satisfactory bilingual dictionary currently available, though both the Oxford and

Collins dictionaries (full length) are usable for the basics. Both can be consulted online, though it would

be very useful for you to possess your own hard copy of one of them, since you will be using it virtually

every day.

Of the monolingual dictionaries, the Diccionario de la Real Academia Española is by far the most

comprehensive and can be accessed free at

www.rae.es. You should get used to using it. On the same

site you will also find the Diccionario panhispánico de dudas, which deals with common grammatical,

lexical and syntactical confusions in all forms of Spanish, and the Diccionario de americanismos, which

lists many thousands of words and expressions (designated by country and region) from across Spanish

America that are not found in peninsular Spanish. Also very useful, particularly with regard to precise

usage of words, is María Moliner’s Diccionario de uso del español (2 vols).

In your first year you will attend a variety of language classes and undertake a range of exercises in

those classes. At the end of the year, you will sit two language exams in Spanish. Paper I will involve

translating a passage of English and also twenty ‘grammatical sentences’ into Spanish. Paper II consists

of two passages in Spanish for translation into English.

Literature

General

Many incoming freshers will not have studied much literature formally prior to coming to Oxford.

Tutors are aware of and sensitive to this, so it should not be a cause of excessive concern. You will

gradually need to develop both a style and, in some cases, a specific critical vocabulary for writing

about literary texts. You will also want to think about what literature is, why people write it and what it

can, does and perhaps should do. A useful starting point for the consideration of these questions is

Warren and Wellek, Theory of Literature. If you want to find out about specific aspects or genres of

literature (for example, ‘metaphor’, ‘realism’, ‘the grotesque’, ‘pastoral’, ‘the short story’, etc.), an

excellent starting point is Routledge’s Critical Idiom series.

If most freshers will have studied at least some literary prose, fewer of you are likely to have much

experience reading and analysing poetry. Doing this well requires a good deal of technical knowledge,

both of rhetorical terms and metrics. You can find a list of the former in the appendix to Brian Vicker’s

In Defence of Rhetoric (Oxford: Clarendon), but better still is Richard Lanham’s A Handlist of

Rhetorical Terms (Berkeley: University of California). For the latter, you might consult Paul Fussell’s

Poetic Metre and Poetic Form (McGraw-Hill) and Phil Robert’s accessible and engaging How Poetry

Works (Penguin). Another very useful general work is Jeffrey Wainwright’s Poetry: The Basics

(London: Routledge), which covers both areas clearly and concisely.

As for Spanish metrics, you could begin by reading the ‘Introduction’ to Janet Perry’s Harrap Anthology

of Spanish Poetry. Another extremely useful primer, full of clear examples and also containing a potted

history of poetic form in Spanish, is Antonio Quilis’s Métrica española (Barcelona: Ariel). The most

technical discussion of the subject is provided by Tomás Navarro in his Métrica española.

Many of you will have done relatively little practical literary criticism when you arrive in Oxford and

may have no experience at all of writing literary commentaries. Again, tutors are aware of this and make

no assumptions about what you ‘should’ be able to do when you begin your degree course. Reading

John Peck and Martin Colye’s Practical Criticism (London: Palgrave) will help you get started.

The above are intended as suggestions of some useful background reading you might want to do before

coming up to Oxford. This is entirely optional, though. The next section details the pre-reading that is

compulsory (and which should, therefore, be your priority).

Set Texts for Papers III and IV

These are the two literature-based papers which you will be required to sit as part of the Preliminary

Examination at the end of your first year. You should obtain all the following texts before you come up

to Oxford, and you should read carefully (that means looking up all the unfamiliar vocabulary) all the

set texts for Paper IV (note the reverse order we’ll study the papers in), as we’ll be covering this paper

over the first term. Ideally, you would read the Paper III texts too before October (since time further

down the line might be tight), though this is not essential. You should try, wherever possible, to get hold

of the editions listed below (where a prescribed edition is designated), though the crucial thing is that

you read the texts (in any edition you can obtain) before you begin your course.

Note that anyone reading Spanish with a Middle Eastern language will only need formally to sit one of

these papers (Paper III). But such students will still follow the full course, including Paper IV, because

it is intended that the first-year course will offer a broad panorama of Hispanic literature that will inform

your paper choices from the start of your second year.

The teaching for these literature papers will involve lectures at the Faculty and college-based tutorials

with me and with one or two other first-year undergraduates.

Paper III: Introduction to Hispanic Prose

Campobello, Nellie, Cartucho, ed. Josebe Martínez (Madrid: Cátedra)

[ISBN-10: 8437634326].

Carpentier, Alejo, El reino de este mundo (Barcelona: Austral) [ISBN-10: 8432224952].

Cervantes, Miguel de, ‘Rinconete y Cortadillo’, in Novelas ejemplares I, ed. Harry Sieber (Madrid:

Cátedra) [ISBN: 9788437602219].

Matute, Ana María, Primera memoria (Barcelona: Destino) [ISBN: 9788423343591], or, alternatively,

within the trilogy Los mercaderes (Barcelona: Austral) [ISBN-10: 8423352781].

Paper IV: Introduction to Hispanic Poetry and Drama

El romancero viejo, ed. Monserrat Díaz Roig (Madrid: Cátedra) [ISBN: 9788437600802]

Poem numbers: 1, 3, 5-9, 14, 18, 38, 40, 50, 52, 54, 56, 66, 68, 72, 76, 86, 97, 97a, 99, 110-11, 117,

121, 125, 127-28.

A selection of Golden Age sonnets (PDF booklet to be made available in due course).

Calderón de la Barca, Pedro, El médico de su honra, ed. Don Cruickshank (Madrid: Castalia) [ISBN-

10: 8497403754].

García Lorca, Federico, Doña Rosita la soltera, ed. Mario Hernández Sánchez (Madrid:

Alianza) [ISBN: 9788420675725].

Vallejo, César, Los heraldos negros, ed. René de Costa (Madrid: Cátedra)

[ISBN-10: 8437616697].

If you have any questions about the above, please do feel free to get in touch. My email address is:

roy[email protected].ac.uk. I hope you enjoy the preparatory reading and I look forward to

meeting you properly in October. A happy summer in the meantime!

Dr Roy Norton

Trinity Term 2024

1

Preliminary Examination in Spanish

The Sonnet in the Spanish Golden Age

2

Introduction 4

Garcilaso de la Vega (Spain, c.1501–1536) 6

1. ’Escrito ‘stá en mi alma vuestro gesto’ (Sonnet v) 7

2. ‘En tanto que de rosa y d’azucena’ (Sonnet xxiii) 7

3. ‘A Dafne ya los brazos le crecían’ (Sonnet xiii) 8

4. ‘A Boscán desde la Goleta’ (Sonnet xxxiii) 9

Francisco de Terrazas (New Spain, 1525? –1580) 11

5. ‘¡Ay basas de marfil, vivo edificio…!’ 12

6. ‘Soñé que de una peña me arrojaba’ 12

Francisco de Aldana (Naples, 1537 – Morocco, 1578) 14

7. ‘¿Cuál es la causa, mi Damón, que estando…?’ 15

Fernando de Herrera (Spain, 1534–1597) 16

8. ‘Osé y temí, mas pudo la osadía’ 17

Luis de Góngora y Argote (Spain, 1561–1627) 18

9. ‘¡Oh claro honor del líquido elemento!’ (Sonetos amorosos XCIII, 1582) 19

10. ‘Mientras por competir con tu cabello’ (Sonetos varios LXVI, 1582) 19

11. ‘Grandes, más que elefantes y que abadas’ (Sonetos satíricos CCXXIII, 1588) 20

12. ‘Menos solicitó veloz saeta’ (Sonetos morales LIV, 29 de agosto de 1623. De la brevedad

engañosa de la vida) 20

Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio (Spain, 1562–1635) 23

13. ‘Versos de amor, conceptos esparcidos’ 24

14. ‘Un soneto me manda hacer Violante’ 24

15. ‘Pastor que con tus silbos amorosos’ 25

16. ‘Dice como se engendra amor, hablando como filósofo’ 26

Sor Ana de la Trinidad (Ana de Arellano y Navarra) (Spain, 1577–1613) 28

17. ‘Entre tantas saetas con que llaga’ (Sonnet 1) 29

18. ‘¡Oh peregrino, bien del alma mía…!’ (Sonnet 4) 29

Francisco de Quevedo Villegas (Spain, 1580–1645) 32

19. ‘Represéntase la brevedad de lo que se vive y cuán nada parece lo que se vivió’

(GS63, B2) 33

20. ‘Afectos varios de su corazón fluctuando en las ondas de los cabellos de Lisi’

(GS269, B449) 33

21. ‘Amor constante más allá de la muerte’ (GS281, B472) 34

22. ‘A un hombre de gran nariz’ (GS416, B513) 34

3

Leonor de la Cueva y Silva (Spain, 1611–1705) 37

23. ‘Introduce un pretendiente, desesperado de salir con su pretensión, que con el

favor de un poderoso la consiguió muy presto’ (Sonnet III) 38

24. ‘Ya ha salido el invierno: ¡albricias, flores!’ (Sonnet XXIII) 39

Juan del Valle y Caviedes (Spain, 1645–Peru,1697) 41

25. ‘Lo que son riquezas del Perú’ 42

26. ‘Remedio para ser caballeros los que no lo son en este’ 42

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez) (New Spain, 1651–1695) 44

27. ‘Procura desmentir los elogios que a un retrato de la poetisa inscribió la verdad,

que llama pasión’ (OC145, Inundación castálida, p.3) 45

28. ‘Que contiene una fantasía contenta con amor decente’ (OC165, Segundo volumen,

p.282) 45

29. ‘Soneto burlesco’ (OC160, Poemas, pp. 43) 46

30. ‘Soneto a san José, escrito según el asunto de un certamen que pedía las metáforas

que contiene’ (OC209, Segundo volumen p.546) 47

4

Introduction

The sonnet was one of the hallmark poetic forms of the early modern period. Its roots in

Spanish lie in the Italianate Petrarchan tradition of love poems, but, over time, it expanded

into an extraordinary range of other genres and themes. Reflecting the breadth and

diversity of the tradition, this anthology features thirty sonnets by eleven authors (men

and women, canonical and lesser-known, from Spain and the Americas). Subjects

explored include romantic love, religious devotion, political ambition, imperial

expansion, and urban life, all intertwined with reflection on the nature of writing itself

and the possibilities—and challenges—of poetic expression.

Recommended background reading (further specific reading is provided for each author,

but the below are a good starting point for understanding the poetry of this period). An

electronic version of the secondary reading lists, with links to e-texts, where available, can

be found here:

https://rl.talis.com/3/oxford/lists/60489DB4-4814-1EAB-5C14-

DE24521BD33E.html

Alonso, A., La poesía italianista (Madrid: Laberinto, 2002)

Cacho Casal, Rodrigo, ‘El ingenio del arte: introducción a la poesía burlesca del Siglo de

Oro’, Criticón, 100 (2007), 9–26

Fucilla, Joseph G., ‘Two Generations of Petrarchism and Petrarchists in Spain’, Modern

Philology, 27.3 (1950), 277–95

Gaylord, Mary, ‘Spain, Poetry of – to 1700’, in Princeton Encyclopedia of Poetry and Poetics,

4

th

ed. (2012)

López Bueno, Begoña, ed. La renovación poética del Renacimiento al Barroco (Madrid: Síntesis,

2006)

Manero Sorolla, M.P. Introducción al estudio del petrarquismo en España. Barcelona, PPU,

1987

Navarrete, Ignacio, Orphans of Petrarch: Poetry and Theory in the Spanish Renaissance (Los

Angeles: UP California, 1994)

Parker, A.A., The Philosophy of Love in Spanish Literature (Edinburgh: Edinburgh UP, 1985)

Prieto, Antonio, La poesía española del siglo XVI (Madrid: Cátedra, 1984)

Rodríguez-Moñino, Antonio, Construcción crítica y realidad histórica en la poesía española de

los siglos XVI y XVII [...] (Madrid, 1963)

Schwartz Lerner, Lía, ‘Golden Age Satire: Transformations of Genre’, Modern Language

Notes, 105 (1990), 260–82

Terry, Arthur, Seventeenth-Century Spanish Poetry (Cambridge, 1993)

Weiss, Julian, ‘Renaissance Poetry’, in The Cambridge History of Spanish Literature, ed.

David Gies (CUP, 2004)

Abbreviations

Auts. = Diccionario de autoridades (1726–1739) (

https://apps2.rae.es/DA.html)

Cov. = Sebastián de Covarrubias Horozco, Tesoro de la lengua castellana (1611)

(https://www.cervantesvirtual.com/obra-visor/del-origen-y-principio-de-la-lengua-

castellana-o-romance-que-oy-se-vsa-en-espana-compuesto-por-el--0/html/)

RAE. = Diccionario de la Real Academia Española, https://www.rae.es

5

6

Garcilaso de la Vega (Spain, c.1501–1536)

Garcilaso’s short life was seen by his early readers to be

the epitome of the Renaissance masculine ideal of arms

and letters, ‘tomando ora [ahora] la espada, ora la

pluma’ as he wrote in his third eclogue. Born into an

aristocratic family in Toledo, Garcilaso spent much of

his life away from Spain in the service of Charles V

(1500-1558) as soldier, courtier and ambassador during

the period in which Spanish hegemony both in Europe

and in its overseas empire was expanded and

consolidated, participating in military campaigns

against the Ottoman Turks and other European powers

until being mortally wounded in an incursion into

southern France. Influential commentators such as

Fernando de Herrera (fig. 1) co-opted Garcilaso’s

poetry, too, as an act of imperial service, elevating

Spanish to the expressive heights of Greek and Latin,

just as the classical poets had done for the Roman

empire. The reality is more complex. Garcilaso’s

relationship with the court was sometimes uneasy – his

brother was implicated in the revolt of the comuneros in

the 1520s, and Garcilaso himself was briefly exiled to the

Danube in the 1530s – and his poetry was circulated privately during his lifetime, only

coming to broader attention with the posthumous publication of Las obras de Boscán y

algunas de Garcilaso de la Vega in 1543.

Garcilaso is now known as one of the foremost ‘new poets’ of sixteenth-century

Europe. These ambitious literary innovators used foreign, unfamiliar language and forms,

usually adapted from the Latin and Italian traditions, to explore the new social,

psychological and political experiences of their period, often through the language of

unrequited love. Together with his friend Juan Boscán (c. 1490-1542), he is the first to

establish the Petrarchan sonnet as a Spanish poetic form. Many of his love poems were

initially thought to arise from a supposed romance with a Portuguese noblewoman, Isabel

Freire, but critics now recognise that most of the corpus resists such a biographical

reading. Rafael Lapesa demonstrated that Garcilaso’s style does evolve over time, initially

working within the late medieval Spanish tradition of courtly love poetry, the cancioneros,

before incorporating Italian and classical influences following his stays in Naples, but

these different currents often coexist. As Mary Gaylord puts it, ‘although often startling

in their movement between the stark conceits and insistent redundancy of cancionero

codes and the copious imagery of Latin and Italian material, [Garcilaso’s sonnets]

nonetheless achieve unprecedented collaboration among these traditions’.

Fig. 1: Obras de Garci Lasso

de la Vega con anotaciones de

Fernando de Herrera (Seville,

1580). Source:

Bibloteca Virtual

Miguel de Cervantes

7

1. ’Escrito ‘stá en mi alma vuestro gesto’ (Sonnet v)

1

Combining the themes of desire, imagination, and their textual representation, this sonnet

acts as a primer for the reader of Garcilaso’s poetry. Drawing on the language of

spiritualised devotion to the beloved from the cancionero tradition, it also presents a more

philosophical reflection on the relationship between perception and desire. Through these

twin strands, the text raises a crucial question: to what extent is the poet’s predicament

about love itself, and to what extent is it a construction in the service of poetic creation?

Escrito ‘stá en mi alma vuestro gesto

2

y cuanto yo escribir de vos deseo:

vos sola lo escribistes; yo lo leo,

tan solo, que aun de vos me guardo en esto.

3

En esto ‘stoy y estaré siempre puesto,

4

5

que aunque no cabe en mí cuanto en vos veo,

de tanto bien lo que no entiendo creo,

tomando ya la fe por presupuesto.

Yo no nascí sino para quereros;

mi alma os ha cortado a su medida; 10

por hábito del alma misma os quiero;

5

Cuanto tengo confieso yo deberos;

por vos nací, por vos tengo la vida,

por vos he de morir y por vos muero.

6

2. ‘En tanto que de rosa y d’azucena’ (Sonnet xxiii)

This sonnet develops the classical topos of carpe diem (‘seize the day’), in which a virginal

woman is counselled to enjoy her beauty before it is ravished by age. The quatrains set

out her beauty in Petrarchan terms, before the tercets introduce a temporal dimension

through allusion to the changing seasons. Which raises the question: in what ways does

the poet stand to gain from the woman’s youth, if he is so concerned about its loss?

1

Poems are taken from Garcilaso de la Vega, Obra poética y textos en prosa, ed. Bienvenido Morros (Barcelona:

Crítica, 2007).

2

gesto = rostro

3

According to the Aristotelian theory of perception, the phantasy, or imagination, only produces images of

objects in their absence (phantasma); it cannot do so while they are present. Furthermore, Aristotle argues

that our desire for anything not present to the senses must be mediated by an image of the desired object (De

anima III.3-11). For another reflection on the role of phantasy in mediating the object of desire, see sonnet 28

in this collection.

4

‘La repetición de en esto al principio de este verso y al final del anterior se llama anadiplosis’ (Herrera).

5

hábito is ambiguous here, and could refer to the item of clothing worn by monks or be read in the sense of

‘custom’, ‘behaviour’. It has also been suggested that the poem can be read as a transposition of the monk’s

religious devotion (marked by allusions to the scriptorium (ll.1-4), contemplation (ll.5-8), and the habit (l.11))

onto the experience of erotic desire.

6

This repetition of the same phrase at the beginning of successive clauses is called anaphora. Here, it serves

to emphasise the paradoxical notion that the love for his beloved gives the poet both life and death.

8

En tanto que de rosa y d’azucena

7

se muestra la color en vuestro gesto,

8

y que vuestro mirar ardiente, honesto,

con clara luz la tempestad serena;

Y en tanto que’l cabello, que’n la vena 5

del oro s’escogió, con vuelo presto

por el hermoso cuello blanco, enhiesto,

9

el viento mueve, esparce y desordena:

coged de vuestra alegre primavera

el dulce fruto, antes que’l tiempo airado

10

10

cubra de nieve la hermosa cumbre.

11

marchitará la rosa el viento helado,

todo lo mudará la edad ligera

por no hacer mudanza en su costumbre.

12

3. ‘A Dafne ya los brazos le crecían’ (Sonnet xiii)

This sonnet dramatises a classical myth famously rendered in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (book

1, lines 452-524) and featured in many works of art, in which the enamoured god Apollo

pursues the unenamoured nymph Daphne, who is transformed into a laurel tree to escape

his assault. Laurel then becomes the symbol of Apollo, the sun god and god of poetry,

and by extension of poets, who are often figured wearing laurel wreaths. In contrast to

Ovid, Daphne’s viewpoint is entirely eliminated here, and the moment of her

metamorphosis is transformed through the first-person verb ‘vi’ into an ekphrasis: a

literary description of a work of art. But who is the viewer?

A Dafne ya los brazos le crecían

y en luengos ramos vueltos se mostraban;

13

en verdes hojas vi que se tornaban

los cabellos qu’el oro escurecían:

14

7

The rose and the lily, representing the colours red and white, were the canonical markers of female beauty

in this period, representing sensuality (red) and honesty or purity (white). En tanto que: the comparator

conveys the Renaissance Neo-platonic understanding of human beauty as a reflection of the natural world.

8

gesto = rostro. The Petrarchan woman is never portrayed as a complete person, but rather as a series of

body parts, each according to a prescribed metaphor.

9

enhiesto: from ‘enhestar’, ‘to raise on end’.

10

coged … el dulce fruto: the key marker of the carpe diem topos, an allusion to Ausonius’ De rosae, v.49

(‘colligio, virgo, rosas’) and to Bernardo Tasso’s Gli amori, fol. 65 ‘cogliete, o giovenette, il vago fiore | dei

vostri più dolci anni’); airado: ‘enojado’,

11

cumbre a reference both to the snow-capped mountain-top and to the ageing women’s grey hair.

12

su costumbre: i.e. ‘de la edad’. The only unchanging thing about age is that it changes everything.

13

‘convertidos en largos ramos’.

14

The comparison of the beloved’s blonde hair to gold is a commonplace of Petrarchan love poetry. A

hyperbole here describes Daphne’s hair as so bright it makes gold look dark by comparison. The descriptio

9

de áspera corteza se cubrían

los tiernos miembros que aun bullendo ‘staban;

15

los blancos pies en tierra se hincaban

y en torcidas raíces se volvían.

Aquel que fue la causa de tal daño,

16

a fuerza de llorar, crecer hacía

este árbol, que con lágrimas regaba.

¡Oh miserable estado, oh mal tamaño,

que con llorarla crezca cada día

la causa y la razón por que lloraba!

4. ‘A Boscán desde la Goleta’ (Sonnet xxxiii)

17

The poem is one of what Richard Helgerson has termed the ‘Tunis cycle’ of Garcilaso’s

poems, written around the time he was participating in Charles V’s defeat of the Moorish

corsair Kheir-ed-Din in northern Africa in 1535. Goleta was a modern fortress near the

ruins of ancient Carthage. The first word of the poem shows that it is framed as an

epistolary sonnet, a missive from the lovesick poet to his faraway friend Boscán.

Boscán, las armas y el furor de Marte,

18

que, con su propia fuerza el africano

suelo regando, hacen que el romano

imperio reverdezca en esta parte,

han reducido a la memoria el arte

19

y el antiguo valor italïano,

por cuya fuerza y valerosa mano

África se aterró de parte a parte.

20

Aquí donde el romano encendimiento,

puellae or formulaic head-toe description of a woman’s beauty is another Petrarchan motif, although here the

body parts (arms, hair, limbs, feet) appear only as they change into something else.

15

The verb ‘bullir’ seems to correspond to the Latin ‘trepidare’, trembling or quivering.

16

‘Aquel’ refers to Apollo, who makes the tree grow with his tears.

17

The title first appears in the 1569 edition of Garcilaso. This poem is not included in the first, 1543 edition

of Garcilaso’s poems.

18

There is an allusion here to the opening of the most canonical Latin epic, Virgil’s Aeneid, arma virumque

cano [I sing of arms and of the man], or, in a well-known alternative version going back to the Roman

commentator Servius, ‘horrentia Martis / arma virumque cano’ [I sing of the bristling arms of Mars and of

the man’]. The man in question is Aeneas, the mythical founder of the city of Rome.

19

Reducir is a cultismo, a word originating in Latin (or occasionally Greek) which is not in common usage

and is used for poetic effect. This example is a cultismo semántico, where a word is used not with its everyday

meaning (in this period, to convince or to subdue) but with its original etymological Latin meaning, reducere,

to bring or lead back.

20

Here, not ‘to terrorise’ but ‘to level to the ground’, recalling the systematic destruction of the city of

Carthage which ended the Punic Wars between the Carthaginian and Roman empires.

10

donde el fuego y la llama licenciosa

21

solo el nombre dejaron a Cartago,

vuelve y revuelve amor mi pensamiento,

hiere y enciende el alma temerosa,

y en llanto y en ceniza me deshago.

Select bibliography

Cruz, Anne J., Imitación y transformación : el petrarquismo en la poesía de Boscán y Garcilaso

de la Vega (Amsterdam: Benjamins, 1988)

Heiple, Daniel L., Garcilaso de la Vega and the Italian Renaissance (University Park, Penn.:

Penn. State UP, 1994)

Helgerson, Richard, A Sonnet from Carthage: Garcilaso de la Vega and the New Poetry of

Sixteenth-Century Europe (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2007)

Rivers, Elias (ed), Garcilaso de la Vega: Poems, (London: Grant & Cutler, 1980) [CGST]

Stanton, Edward F., ‘Garcilaso’s Sonnet XXIII’, Hispanic Review, 40.2 (1972): 198-205

21

The ‘licentious flame’ refers to Dido, queen of Carthage, and her doomed love for Aeneas, in book four of

the Aeneid. When Aeneas abandons her, she commits suicide, and on her funeral pyre curses her lover and

his descendants, thus foreshadowing the later Punic Wars and the eventual devastation of the city she had

founded.

11

Francisco de Terrazas (New Spain, 1525? –1580)

The composition of poetry in Spanish in the early Americas dates back to the wars of

conquest and continues unabated throughout the colonial period. Terrazas is the first poet

whose name has survived to us to have been born in (rather than migrating to) the

viceroyalty of New Spain (i.e. in Spanish, a criollo), a vast administrative territory

comprising Mesoamerica with its capital in the viceregal court of Mexico City. His father

was a conquistador who had fought alongside Hernán Cortés, and Terrazas seems to have

spent his life in Mexico City. He soon acquired fame as a writer which brought him both

accolades and trouble. Five of his sonnets feature in the manuscript anthology Flores de

baria poesía, compiled in Mexico in 1577 but soon making its way to Spain, and his poetry

was known to Peninsular authors such as Miguel de Cervantes, who wrote in La Galatea

(1585), ‘Terrazas, tiene | el nombre acá y allá tan conocido’, suggesting a poetic reputation

which had spread to both sides of the Atlantic. Not all of his literary output was so

uncontroversial: a pasquín (a satirical composition, often attacking a particular individual

and affixed anonymously to a prominent urban landmark) and a theatrical piece landed

him in prison in 1574 together with his friend and fellow poet Fernán González de Eslava

(c. 1534-1601), and he also intervened in a polemical poetic debate, whose context remains

murky, about the relationship between the Law of Moses (i.e. the Jewish Law of the Old

Testament) and the Law of Christ.

As with many colonial American (and indeed Spanish) authors of this period,

Terrazas’s works were not printed during his lifetime, and more of them are missing than

those that survive. The extant works comprise ten sonnets, a love letter in verse, the

theological poems mentioned above, and fragments of a narrative epic poem on Cortés,

Nuevo mundo y conquista. Those that survive show a man of wide culture, familiar with

Latin verse and contemporary innovations in Italian poetry, and able to utilise and parody

the conventions of Petrarchan and Neo-Platonic love to create surprising and sometimes

provocative effects.

12

5. ‘¡Ay basas de marfil, vivo edificio…!’

1

The comparison of the human body to a building goes back to classical antiquity. Petrarch,

in his canzione ‘Tacer non posso’, compared the beloved Laura’s body to a beautiful prison

of her soul made of precious materials. The notion that the female body is God’s

masterpiece and that contemplation of its beauty can lead to an ascent towards

contemplation of the higher beauty of the Creator is a key tenet of Renaissance Neo-

Platonic thought. The Petrarchan descriptio puellae, however, usually contemplated a

woman’s body from head to waist before jumping decorously to the feet. But here the poet

is fixated on what lies in between…

¡Ay, basas de marfil, vivo edificio

2

obrado del artífice del cielo,

columnas de alabastro que en el suelo

3

nos dais del bien supremo claro indicio!

4

¡Hermosos chapiteles y artificio

5

del arco que aún de mí me pone celo!

¡Altar donde el tirano dios mozuelo

6

hiciera de sí mismo sacrificio!

¡Ay, puerta de la gloria de Cupido,

y guarda de la flor más estimada

7

de cuantas en el mundo son ni han sido!

Sepamos hasta cuándo estáis cerrada

y el cristalino cielo es defendido

a quien jamás gustó fruto vedado.

6. ‘Soñé que de una peña me arrojaba’

The Petrarchan ‘dream poem’, often used as an outlet for erotic wish fulfilment not

realisable in the waking world of impossible love objects, here turns into a vividly

imagined nightmare.

Soñé que de una peña me arrojaba

quien mi querer sujeto a sí tenía,

8

1

Poems are taken from Raquel Chang-Rodríguez, ed., “Aquí, ninfas del Sur, venid ligeras”: voces poéticas

virreinales (Madrid: Iberoamericana, 2008).

2

basa = ‘El asiento de la columna’ (Cov.)

3

cf. the Biblical Song of Songs, which praise the bride’s legs as (in Fray Luis de León’s sixteenth-century

translation) ‘columnas de mármol, fundadas sobre basas de oro fino’.

4

According to St Augustine, ‘The highest good, than which there is no higher, is God […] All other good

things are only from Him, not of Him’.

5

chapitel: ‘el remate de la torre alta, en forma de pirámide […] cubre la cabeza y altura de la torre’ (Cov.)

6

Cupid, who is often depicted as a mischievous boy.

7

Here, probably meaning keyhole (Cov., guardas).

8

querer = voluntad.

13

y casi ya en la boca me cogía

una fiera, que abajo me esperaba.

Yo, con temor, buscando procuraba

de dónde con las manos me tendría,

y el filo de una espada la una asía

9

y en una yerbezuela la otra hincaba.

La yerba, a más andar, la iba arrancando;

la espada, a mí la mano deshaciendo,

yo, más sus vivos filos apretando.

¡Oh, mísero de mí, qué mal me entiendo,

pues huelgo verme estar despedazando

10

de miedo de acabar mi mal muriendo!

11

Select bibliography

Chang-Rodríguez, Raquel, “Aquí, ninfas del sur, venid ligeras”: Voces poéticas virreinales

(Madrid: Iberoamericana, 2008), introduction and pp. 131-38

Flores de baria poesía, ed. Margarita Peña (Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2004)

Íńigo Madrigal, Luis, ‘Sobre el soneto de Terrazas “¡Ay, basas de marfil, vivo edificio!”’,

Anales de Literatura Hispanoamericana (25), 1996

9

asir = agarrar.

10

holgar = ‘alegrarse de una cosa’ (RAE).

11

‘mal’ can refer to any kind of trouble or illness, but is often used in love poetry to signify the mal de amor,

love sickness.

14

Francisco de Aldana (Naples, 1537 – Morocco, 1578)

Fig. 1: view of Florence, in Hartmann Schedel, Nuremberg Chronicle (=Liber chronicarum), 1493, fol. 87.

Francisco de Aldana was one of the leading lights of the second generation of Spanish

Renaissance poets. Born in 1537, probably in Naples, where his father served as captain

in the forces of the viceroy Pedro de Toledo, he was brought up in the cultured world of

Renaissance Italy. Like Garcilaso, and others (e.g. Cetina, Acuña), Aldana was a soldier-

poet. After early years in Naples, and then a lengthy formative period at the humanist

court of Cosimo de’ Medici in Florence, he participated in military campaigns in Flanders,

France, and North Africa. He relocated to Spain in 1576, and his last years were spent in

the service of Philip II’s nephew, King Sebastian of Portugal. In 1578, whilst leading the

infantry in Sebastian’s expedition in North Africa, he was killed, together with Sebastian

and large numbers of Portuguese nobles, at the Battle of Alcazarquivir (Ksar el-Kebir) in

Morocco.

Long neglected in later centuries, ‘el divino capitán’ was held in the highest regard by

Golden Age writers of the stature of Cervantes, Lope, and Quevedo. Shaped by his

immersion in the culture of Renaissance Italy, specifically Florence, Aldana’s poetry

betrays the influence not only of Petrarchism but also of Neoplatonic philosophy.

Aldana’s most famous poem, the 451-line epistle entitled ‘Carta para Arias Montano sobre

la contemplación de Dios y los requisites della’, is a ‘profound and moving meditation on

friendship as a pathway to Divine contemplation’ (Weiss, ‘Renaissance Poetry’, p. 172).

Aldana’s other poems range from sonnets on love (and other subjects) to longer pieces on

religious themes, classical mythology, and earlier Italian and Spanish works. As with

Garcilaso, his poetry appeared only posthumously; Aldana’s poems were collected by his

brother, Cosme, and published more than a decade after his death in two parts dedicated

to Philip II (Milan, 1589; Madrid, 1591).

15

7. ‘¿Cuál es la causa, mi Damón, que estando…?’

Aldana’s most famous sonnet, this snatch of dialogue between two lovers is striking for

its explicit references to reciprocated physical love (post-coital tristesse?), play with

established dynamics (notably, female/male and body/soul), and the image of the sponge

soaked with water in the second tercet.

‘¿Cuál es la causa, mi Damón, que estando

en la lucha de amor juntos, trabados

con lenguas, brazos, pies, y encadenados

cual vid entre el jazmín se va enredando,

1

y que el vital aliento ambos tomando

en nuestros labios, de chupar cansados,

en medio a tanto bien somos forzados

llorar y sospirar de cuando en cuando?’

‘Amor, mi Filis bella, que allá dentro

nuestras almas juntó, quiere en su fragua

los cuerpos ajuntar también tan fuerte

que no pudiendo, como esponja el agua,

pasar del alma al dulce amado centro,

llora el velo mortal su avara suerte.’

2

Select Bibliography

Aldana, Francisco de, Poesías castellanas completas, ed. José Lara Garrido, Letras

Hispánicas, 223 (Madrid: Cátedra, 2000)

Lennon, Paul Joseph, ‘The Nature of Love’, in his Love in the Poetry of Francisco de Aldana

(Woodbridge: Tamesis, 2019), pp. 89–123

Rutherford, John, ‘Francisco de Aldana (1537–1578)’, in his The Spanish Golden Age Sonnet

(Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2016), pp. 97–107

Terry, Arthur, ‘Thought and Feeling in Three Golden-Age Sonnets’, Bulletin of Hispanic

Studies, 59 (1982), 237–46

Walters, Gareth, The Poetry of Francisco de Aldana (London: Tamesis, 1988)

1

vid/jazmín: ‘vine’ and ‘jasmine’ intertwined, a simile for the lovers’ entangled bodies and limbs.

2

velo mortal: the body as the soul’s ‘mortal veil’; water soaks into the sponge, but the body cannot fuse with

the lover’s soul, giving rise to another form of unfulfilled desire.

16

Fernando de Herrera (Spain, 1534–1597)

Fig. 1: ‘Fernando de Herrera el Divino’, in Francisco Pacheco, El libro de descripción de verdaderos retratos

de ilustres y memorables varones, Seville, 1599.

Fig. 2: Fernando de Herrera, Algunas obras (Seville: Andrea Pescioni, 1582)

Born into a humble yet respectable family in 1534, Fernando de Herrera, who also came

to be known as ‘el Divino’, spent all his life in the Andalusian city of Seville. He did not

attend university, but he received a strong humanist education and, in taking minor

orders (by 1566), secured a modest income. Resisting offers of higher station, he dedicated

himself to study, developing a reputation as a scholar, linguist, and something of a

polymath. In ‘Seville’s golden age of letters’, he rose to prominence as a leading member

of the city’s literary and artistic circles, becoming most associated with the learned

academy initially led by the humanist Juan de Mal Lara (other members included

Francisco Pacheco, uncle to the painter of the same name, and Francisco de Medina).

1

Mal

Lara’s circle often met at the palace of their noble patron, the Count of Gelves, whose wife,

Leonor, is held to have been the muse for Herrera’s own love lyric.

One of the most influential writers of the second half of the sixteenth century, Herrera

is famous both as a literary critic and as a poet in his own right. Following a 1574 study

by El Brocense, Herrera’s edition of and commentary on Garcilaso, the mammoth 691-

page Anotaciones (1580), further cemented Garcilaso’s status as a classic. It also sets out

Herrera’s own theory of poetry, and poetic language, providing an important stepping-

stone to Góngora’s elitist and aristocratic verse. Like other poets of the period, Herrera

wrote in a variety of forms, and on a variety of subjects, but his songbook of love poems

to ‘Luz’ (elsewhere, e.g. ‘Lumbre’, ‘Estrella’), in imitation of Petrarch’s Canzoniere, has best

stood the test of time. Unusually, a volume of his poems—Algunas obras (Seville, 1582)—

was printed in his own life, soon after the death of his patrons (an expanded volume was

published in 1619, also in Seville, under the direction of Pacheco, the painter). Herrera

wrote less poetry after the appearance of the 1582 volume, and his collection of endlessly

revised papers disappeared on his death in 1597.

1

Jonathan Brown, ‘A Community of Scholars’, in his Images and Ideas in Seventeenth-Century Spanish Painting

(Princeton: Princeton UP, 1978), pp. 21–43 (at p. 25).

17

8. ‘Osé y temí, mas pudo la osadía’

The opening poem of Algunas obras, this prefatory sonnet sets the tone for Herrera’s

songbook. Drawing on conventions of courtly devotion (ascent, servitude), it establishes

the theme of osadía, contrasting the daring of youth with the wisdom of experience. The

poetic voice recognises the error of their younger ways, but can they choose a different

path?

Osé y temí, mas pudo la osadía

tanto que desprecié el temor cobarde;

subí a do el fuego más me enciende y arde

cuanto más la esperanza se desvía.

2

Gasté en error la edad florida mía,

ahora veo el daño, pero tarde,

que ya mal puede ser que el seso guarde

a quien se entrega ciego a su porfía.

3

Tal vez pruebo —mas, ¿qué me vale?— alzarme

del grave peso que mi cuello oprime,

aunque falta a la poca fuerza el hecho.

Sigo al fin mi furor, porque mudarme

no es honra ya, ni justo que se estime

tan mal de quien tan bien rindió su pecho.

Select Bibliography

Herrera, Fernando de, Poesía castellana original completa, ed. Cristóbal Cuevas, Letras

Hispánicas, 219 (Madrid: Cátedra, 1997)

Middlebrook, Leah, ‘Heroic Lyric’, in her Imperial Lyric: New Poetry and New Subjects in

Early Modern Spain (University Park: Pennsylvania State UP, 2009), pp. 138–74

Navarrete, Ignacio, ‘Love and Allusion: Petrarch and Garcilaso in the Poetry of Herrera’,

in his Orphans of Petrarch: Poetry and Theory in the Spanish Renaissance (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1994), pp. 168–89

Terry, Arthur, ‘The Inheritance’, in Seventeenth-Century Spanish Poetry: The Power of Artifice

(Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1993), pp. 1–34

Torres, Isabel, ‘Fernando de Herrera (1534–1597): ‘Righting’ the Middle – Centres, Circles

and Algunas Obras (1582)’, in her Love Poetry in the Spanish Golden Age: Eros, Eris and

Empire (Woodbridge: Tamesis, 2013), pp. 60–94

Valencia, Felipe, ‘The Apollonian and Orphic Masculinity of Fernando de Herrera’s

Algunas obras (1582)’, in his The Melancholy Void: Lyric and Masculinity in the Age of

Góngora (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2021), pp. 87–123

2

subí a do el fuego más me enciende: the notion of daring ascent towards fire recalls the classical tales of

Icarus and Phaethon, Renaissance shorthand for the folly of (youthful) overambition.

3

porfía: ‘Una instancia y ahínco en defender alguno su opinión o constancia en continuar alguna pretensión’

(Cov.).

18

Luis de Góngora y Argote (Spain, 1561–1627)

Fig. 1: Velázquez (attrib.), Luis de Góngora, 1622 (Boston, Museum of Fine Arts)

Fig. 2: title-page of the Chacón MS (Biblioteca Nacional de Madrid, Ms. Res 45, p. 1)

Born in Córdoba, Góngora was the eldest son of the cultured Francisco de Argote and the

classier Leonor de Góngora, from whom Luis took his surname. In 1576, a bachelor uncle

paid for him to enter the University of Salamanca to study canon law, but Luis developed

a reputation for frivolity and left Salamanca without a degree. He nevertheless inherited

his uncle’s position at Córdoba cathedral in 1585, frequently travelling north on cathedral

business thereafter. In 1603, he visited Valladolid (home to the court in 1601–6), where his

poetry attracted notice from grandee patrons close to Philip III’s all-powerful valido, the

duke of Lerma. In 1617, Lerma secured Góngora a post as royal chaplain. Góngora settled

in Madrid in the hope of further preferment, but Lerma soon fell, and the poet’s principal

patrons were eliminated. Góngora spent the rest of his life in penury as a pretendiente,

lodged not far from Lope de Vega. He hatched a plan to raise cash by selling his collected

poems to a publisher. However, work was cut short by a stroke in 1625, and he died two

years later, back in his family home in Córdoba.

A lifelong experimenter, Góngora composed in most poetic forms, high and low. His

early work includes beautifully crafted sonnets and sentimental or humorous ballads. His

fellow Andalusian, Pedro de Espinosa drew heavily from Góngora, and the younger

Quevedo (less so, Lope), in his influential anthology, Flores de poetas ilustres de España

(1605). Changing gear in the early 1610s, Góngora honed a self-consciously erudite and

challenging style characterised by highly wrought Latinisms, learned conceits, daring

metaphors, cryptic allusions to mythology, and dense rhetoric. His major poems (the

Polifemo and Soledades) unleashed a firestorm of polemic, shaping the course of poetry for

decades. Góngora influenced not only admirers such as Calderón and Sor Juana (see

below, n.27), but even detractors like Lope and Quevedo. Having fallen into disrepute in

the eighteenth century, he was resuscitated by the French symbolists and the poets of

Spain’s Generation of 1927, so called in homage to the tercentenary of Góngora’s death.

19

9. ‘¡Oh claro honor del líquido elemento!’ (Sonetos amorosos XCIII, 1582)

1

A fine example of the Renaissance doctrine of imitation—notably, in its dialogue with

Bernardo Tasso’s sonnet ‘O puro, o dolce, o fiumicel d’argento’—, this poem engages with

the Orphic conceit that a river might carry a reflection of the beloved’s face or the echo of

their name down to the sea (see, for example, Garcilaso, Égloga III. 246–47).

¡Oh claro honor del líquido elemento!,

2

dulce arroyuelo de corriente plata,

cuya agua entre la hierba se dilata

con regalado son, con paso lento,

pues la por quien helar y arder me siento, 5

mientras en ti se mira, Amor retrata

de su rostro la nieve y la escarlata

en tu tranquilo y blando movimiento,

vete como te vas, no dejes floja

la undosa rienda al cristalino freno 10

con que gobiernas tu veloz corriente,

que no es bien que confusamente acoja

tanta belleza en su profundo seno

el gran señor del húmido tridente.

3

10. ‘Mientras por competir con tu cabello’ (Sonetos varios LXVI, 1582)

An overt tribute to Garcilaso, this sonnet imitates the carpe diem theme and structure of

Garcilaso’s Sonnet XXIII ‘En tanto que de rosa y de azucena’ (above, no. 2 in this

anthology), but pushes the envelope through hyperbole, agudeza, play with symmetry,

and the final inflection into desengaño.

Mientras por competir con tu cabello

oro bruñido al sol relumbra en vano,

mientras con menosprecio en medio el llano

mira tu blanca frente el lilio bello,

mientras a cada labio, por cogello, 5

siguen más ojos que al clavel temprano,

y mientras triunfa con desdén lozano

del luciente cristal tu gentil cuello,

1

Headings and dates for the four Góngora sonnets are taken from the Chacón MS, prepared by the poet’s

friend Antonio Chacón Ponce de León for the Count-Duke of Olivares and completed in December 1628.

2

l. 5 of Tasso’s sonnet reads ‘O primo honor del liquido elemento’; compare, also, l. 12 of Tasso’s poem,

which begins ‘Ferma il tuo corso…’ [Stop your flow…], with Góngora’s volta in l. 9, ‘vete como te vas’.

3

el gran señor del húmido tridente: Neptune, his traditional attribute being the trident, i.e. the sea.

20

goza cuello, cabello, labio y frente,

4

antes que lo que fue en tu edad dorada 10

oro, lilio, clavel, cristal luciente

no sólo en plata o víola troncada

se vuelva, mas tú y ello juntamente

en tierra, en humo, en polvo, en sombra, en nada.

11. ‘Grandes, más que elefantes y que abadas’ (Sonetos satíricos CCXXIII, 1588)

A glittering burlesque of the evils of the court, this sonnet develops a series of paradoxical,

surreal images based on flashing puns. It drives, through its accumulation of laddish

wordplay and jibes, towards the punch in the final line.

Grandes, más que elefantes y que abadas,

títulos liberales como rocas,

gentiles hombres sólo de sus bocas,

illustri cavaglier, llaves doradas;

5

hábitos—capas, digo, remendadas—, 5

damas de haz y envés, viudas sin tocas,

carrozas de ocho bestias (y aun son pocas,

con las que tiran y que son tiradas);

6

catarriberas, ánimas en pena,

con Bártulos y Abades la milicia, 10

y los derechos con espada y daga;

7

casas y pechos, todo a la malicia;

lodos con perejil y hierbabuena:

esto es la Corte. ¡Buena pro les haga!

8

12. ‘Menos solicitó veloz saeta’ (Sonetos morales LIV, 29 de agosto de 1623. De la brevedad

engañosa de la vida)

Much later, and dated to the day, this sonnet engages in moral introspection on the nature

of human life, fleeting and deceptive. It is addressed to Góngora’s poetic alter ego, Licio,

4

goza: the imperative is a hallmark of the ‘carpe diem’ tradition (see Horace, Odes, I.11.8); a different approach

to the subject is found in Góngora’s ballad ‘¡Que se nos va la Pascua, mozas!’, also from 1582.

5

gentilhombres de la boca and caballeros de la llave dorada were ‘gentlemen of the royal chamber’ (Cov.).

6

hábitos: the uniform of knights decorated with the prestigious cross of e.g. the order of Santiago. sin toca:

‘en cabeza loca, poco dura toca’ (Correas); the toca or headscarf was the emblem of the matron or married

woman. carrozas: ‘four-horse coaches’; ocho thus underlines the animalistic nature of the passengers inside.

7

catarriberas: ‘retrievers’ (dogs, in hunting), i.e. pretendientes, hangers-on waiting for preferment. Bártulos y

Abades: Bartolus of Saxoferrato and the Abbot of Palermo (Panormitanus), authorities on civil and canon

law; soldiers become embroiled in lawsuits, while lawyers have recourse to arms.

8

casa a la malicia: ‘la que está edificada en forma que no se puede dividir para haber en ella dos moradores;

así evitaban la obligación de alojar a los criados del rey’ (Cov.). perejil and yerbabuena: ‘parsley and mint’,

slang euphemisms for excrement. Buena pro les haga: ‘much good may it do them.’

21

and is memorable for its compressed Latinate opening, its use of metaphors and symbols

drawn from the classical world, and the devastatingly lucid chain in the closing lines.

Menos solicitó veloz saeta

destinada señal que mordió aguda,

agonal carro por la arena muda

no coronó con más silencio meta,

que presurosa corre, que secreta 5

a su fin nuestra edad.

9

A quien lo duda,

fiera que sea de razón desnuda,

cada sol repetido es un cometa.

10

¿Confiésalo Cartago, y tú lo ignoras?

11

Peligro corres, Licio, si porfías 10

en seguir sombras y abrazar engaños.

Mal te perdonarán a ti las horas,

las horas que limando están los días,

los días que royendo están los años.

Select Bibliography

Alonso, Dámaso, Estudios y ensayos gongorinos, 2nd edn (Madrid: Gredos, 1960; 1st ed.

1955)

Calcraft, R. P., The Sonnets of Góngora (Durham: Durham University Press, 1980)

Góngora, Luis de, Sonetos completos, ed. Biruté Ciplijauskaité, Clásicos Castalia, 1 (Madrid:

Castalia, 1985)

------, Sonetos, ed. Juan Matas Caballero, Letras Hispánicas, 818 (Madrid: Cátedra, 2019)

Jammes, Robert, Études sur l’œuvre poétique de Don Luis de Góngora y Argote, Bibliothèque

de l’École des hautes études hispaniques, 40 (Bordeaux: Féret et Fils, 1967)

Navarrete, Ignacio, ‘Góngora and the Poetics of Fulfillment’, in his Orphans of Petrarch:

Poetry and Theory in the Spanish Renaissance (Berkeley: University of California Press,

1994), pp. 191–205

Rutherford, John, ‘Luis de Góngora y Argote (1561–1627)’, in his The Spanish Golden Age

Sonnet (Cardiff: University of Wales Press, 2016), pp. 117–49

Terry, Arthur, ‘Luis de Góngora: The Poetry of Transformation’, in his Seventeenth-Century

Spanish Poetry: The Power of Artifice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), pp.

65–93

9

agonal: relating to the Agonalia, a festival/games in honour of Agonius/Janus, celebrated in Rome (see Cov.,

on ‘Agonales fiestas’, s.v. agonía). meta: another Latinism, ‘the conical columns set in the ground at each end

of the Roman Circus, the goal, turning-post’ (Lewis & Short). The image of speed corresponds to the title-

word brevedad; the idea of silence, to engaño(sa).

10

cometa: a harbinger of doom.

11

Cartago: the great city of Carthage, razed to the ground by the Romans, was Antiquity’s finest exemplum

of mutability, transience, and the vanity of power and greatness.

22

Thompson, Colin, ‘The Late Sonnets (1623): “En este occidental, en este, oh Licio” and

“Menos solicitó veloz saeta”: On the Last Things’, in A Poet for All Seasons: Eight

Commentaries on Góngora, ed. Oliver J. Noble Wood and Nigel Griffin (New York:

Hispanic Seminary of Medieval Studies, 2013), pp. 211–27

23

Félix Lope de Vega y Carpio (Spain, 1562–1635)

Nicknamed by his contemporaries ‘el fénix de los ingenios’, the phoenix of wits, referring

to the mythical and unique bird which could regenerate itself from its ashes, Lope was

famed from his own day for his prodigious capacity for literary invention, and self-

reinvention. Born in Madrid of relatively humble origins, Lope was one of the first truly

professional writers of his age. While most authors exercised writing as a pastime – at

least in principle – Lope was able to make a living not through nobility of birth, or entering

the Church, the university, the army or the court, but directly through his own pen and

intellect, although this didn’t stop him seeking patronage too. Lope was, and is, best

known as a playwright: his youth coincided with the creation of Spain’s first commercial

theatres, the corrales, and he was widely seen as the inventor of a new form of drama, the

comedia nueva, which remained predominant throughout the Golden Age. However, he

wrote prolifically in multiple genres, composing three epic poems, prose fiction, semi-

autobiography, letters and shorter poetry of all kinds throughout his long career.

As Jonathan Thacker and Alexander Samson put it, ‘the confusion and conflation

of Lope’s life and art in his own work is systematic and deliberate’, and this is nowhere

more apparent than in his lyric poetry. In Lope’s youth, his ballads (romances) were widely

read and performed, in which he created different personas (a lovelorn shepherd, a

Moorish warrior) to voice aspects of his scandalous early love life, which had resulted in

him being exiled from Madrid for libel when his relationship with a married actress, Elena

Osorio, came to a stormy end. The sonnets are the work of a more mature and established

poet keen to secure a lasting reputation. Those represented here come from his three major

anthologies: the Rimas (1602), some two hundred love poems, the Rimas sacras (1614),

poems of divine love, and the Rimas humanas y divinas del licenciado Tomé de Burguillos

(1634), in which he again creates an alter ego, this time the antiheroic, impoverished

graduate (licenciado) Tomé, who is hopelessly in love with a down-to-earth

washerwoman, Juana. One further sonnet comes not from an anthology but from a

comedia – a reminder of the rich cross-over between plays and poetry in the period, and of

the fact that even the most immediate ‘yo’ of love lyric is a carefully constructed

performance.

24

13. ‘Versos de amor, conceptos esparcidos’

1

This prefatory sonnet opens Lope’s Rimas not, as is conventional, by addressing the

reader, or even the beloved, but the poems themselves, which, in an elaborate

‘concepto’, conceit, are compared to abandoned children.

Versos de amor, conce[p]tos esparcidos

engendrados del alma en mis cuidados;

2

partos de mis sentidos abrasados,

con más dolor que libertad nacidos;

espósitos

3

al mundo en que, perdidos,

tan rotos anduviste[i]s y trocados,

que sólo donde fuiste[i]s engendrados

fuérades

4

por la sangre conocidos;

pues que le hurtáis el Laberinto a Creta,

5

a Dédalo los altos pensamientos,

la furia al mar, las llamas al abismo,

si aquel áspid

6

hermoso no os ace[p]ta,

dejad la tierra, entretened los vientos:

7

descansaréis en vuestro centro mismo.

14. ‘Un soneto me manda hacer Violante’

8

This ‘sonnet on the sonnet’ appears in Lope’s play La niña de plata (1607). Combining the

poet’s usual romantic predicament with a literary one, it takes the self-referentiality of the

Petrarchan tradition to its logical extreme, thus also exposing its own artificiality.

Un soneto me manda hacer Violante

9

que en mi vida me he visto en tanto aprieto;

catorce versos dicen que es soneto;

1

Lope de Vega, Rimas, ed. Felipe Pedraza Jiménez (Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, 1993), vol. 1.

2

Hyperbaton: the sense is ‘engendrados en mis cuidados del alma’, engendered in my heart (‘soul’) felt

cares/woes. ‘cuidado’ can mean a care, or a love interest.

3

Niños espósitos were those abandoned, usually at birth, by their parents.

4

Fuérades: antiquated form of the imperfect subjunctive, fuerais/fueseis.

5

The legendary labyrinth of Crete was constructed by the master craftsman, Daedalus, to house and hide the

minotaur. The verses ‘steal’ Crete’s labyrinth, Daedalus’s exalted thoughts, the sea’s fury and hell’s flames

in the sense that they surpass them.

6

áspid: asp, a poisonous snake, here the conventionally unyielding beloved.

7

Unheeded words were conventionally said to be scattered to the winds.

8

Lope de Vega, Poesía. Antología, ed. Miguel García-Posada (Madrid: Espasa-Calpe, 1992), p.326. In La niña

de plata, it is spoken by the gracioso, Chacón, who claims it has won a poetry competition (ll.2608-2622).

9

The ‘sonnet on the sonnet’ is a genre of Spanish origin, much imitated in later poetry. It is first seen in 1605

in Diego Hurtado de Mendoza’s ‘Pedís, Reyna, un soneto, y ya le hago’, which was doubtless known to Lope.

25

burla burlando van los tres delante.

10

Yo pensé que no hallara consonante,

y estoy a la mitad de otro cuarteto;

mas si me veo en el primer terceto,

no hay cosa en los cuartetos que me espante.

Por el primer terceto voy entrando,

y parece que entré con pie derecho,

11

pues fin con este verso le voy dando.

Ya estoy en el segundo, y aun sospecho

que voy los trece versos acabando;

contad si son catorce, y está hecho.

15. ‘Pastor que con tus silbos amorosos’

12

Overlap between sacred and secular love poetry is extremely common in the pre-

modern period, and was not usually perceived as jarring. Garcilaso’s poems were

turned ‘a lo divino’, into devotional versions, by Sebastián de Córdoba in 1575, and

Lope’s penitential address to Jesus as ‘pastor’ follows in this tradition. Both Jesus and

God the Father are in various passages of the Bible the Good Shepherd, guiding and

protecting the flock, but this image is here conflated with the lovesick shepherds of

pastoral literature, while the shepherd’s crook becomes the cross.

Pastor que con tus silbos amorosos

Me despertaste del profundo sueño;

13

Tú que hiciste cayado de este Leño

14

En que tiendes los brazos poderosos;

Vuelve los ojos a mi fe piadosos,

Pues te confieso por mi amor y dueño,

Y la palabra de seguirte empeño

Tus dulces silbos y tus pies hermosos.

Oye, pastor, pues por amores mueres:

No te espante el rigor de mis pecados,

Pues tan amigo de rendidos eres.

15

Espera, pues, y escucha mis cuidados;

10

burla burlando: A colloquial phrase, describing the nonchalance with which a difficult or threating action

is made to look easy or harmless. Often rendered in the expression, ‘burla burlando, vase el lobo al asno’.

11

entrar con pie derecho: ‘empezar a dar acertadamente los primeros pasos en un asunto’ (RAE). There is

also a pun here on the metrical ‘foot’.

12

Lope de Vega, Rimas sacras, ed. Antonio Carreño and Antonio Sánchez Jiménez (Madrid: Iberoamericana,

2006), no. 18/XIV.

13

Building on Jesus’s parables, being in a state of sin is often described as being asleep, while repentance and

conversion is like waking up. The Rimas sacras appeared in the same year Lope was ordained a priest, already

in his fifties, at the end of an extended period of personal and professional crisis.

14

leño: the wood of the cross.

15

rendido: abject, surrendered (to love); in the courtly love tradition, the opposite of riguroso – cruel,

unmoved.

26

¿pero cómo te digo que me esperes,

si estás para esperar los pies clavados?

16. ‘Dice como se engendra amor, hablando como filósofo’

16

The Rimas humanas y divinas are part of Lope’s ciclo de senectute, works of his old age,

which are marked by illness, bereavements and disappointments, but not without

humour. This sonnet parodies Garcilaso’s sonnet VIII but also some of Lope’s own

earlier work. Tomé is expounding according to the best scientific and Neoplatonic

principles of his day the corporeal experience of falling in love – but it appears that his

listener has other things on her mind.

Espíritus sanguíneos vaporosos

suben del corazón a la cabeza

y saliendo a los ojos su pureza

pasan a los que miran amorosos.

17

El corazón opuesto los fogosos

rayos sintiendo en la sutil belleza

como de ajena son naturaleza

18

inquiétase en ardores congojosos.

Estos puros espíritus que envía

tu corazón al mío, por extraños

me inquietan, como cosa que no es mía.

Mira, Juana, qué amor, mira qué engaños,

pues hablo en natural filosofía

a quien me escucha jabonando paños.

Select bibliography

García Santo-Tomás, E., ‘Lope, ventrílocuo de Lope: capital social, capital cultural y

estrategia literaria en las Rimas de Tomé de Burguillos (1634)’, Bulletin of Hispanic

Studies 77 (2000): 287-303

Gaylord Randel, Mary, ‘Proper Language and Language as Property: the Personal

Poetics of Lope’s Rimas’, MLN, 101.2 (1986), 220-46

Samson, Alexander, and Jonathan Thacker, eds, A Companion to Lope de Vega

(Woodbridge: Tamesis, 2008), esp. ‘Introduction: Lope’s Life and Work’; chapter

4, Tyler Fisher, ‘Imagining Lope’s Poetry in the “Soneto primero” of the Rimas’;

16

Lope de Vega, Rimas humanas y divinas del licenciado Tomé de Burguillos, ed. Ignacio Arellano (Madrid:

Iberoamericana, 2021), no. 19.

17

Essentially, warm blood passes from beloved’s heart, to her head, and sends out warm rays through her

eyes to those of her admirer (in this period, the eyes were thought to be active as well as passive organs,

sending out rays which could cause a powerful emotional effect in those they encountered). Lovers were

often said to be able to communicate in this way from eye/heart/soul to soul, without the use of words.

18

Hyperbaton: ‘como son de ajena naturaleza’ (i.e. the rays have reached the lover’s heart, where they are

detected as a foreign force and cause ‘ardores congojosos’).

27

chapter 5, Arantza Mayo, ‘”Quien en virtudes emplea su ingenio…”: Lope’s

Religious Poetry’; chapter 6, Isabel Torres, ‘Outside In: the Subject(s) at Play in

Las rimas humanas y divinas de Tomé de Burguillos’

Weber, Alison, ‘Lope de Vega’s Rimas sacras: Conversion, Clientage, and the

Performance of Masculinity’, PMLA, 2005 (120.2), 404-21

28

Sor Ana de la Trinidad (Ana de Arellano y Navarra) (Spain, 1577–1613)

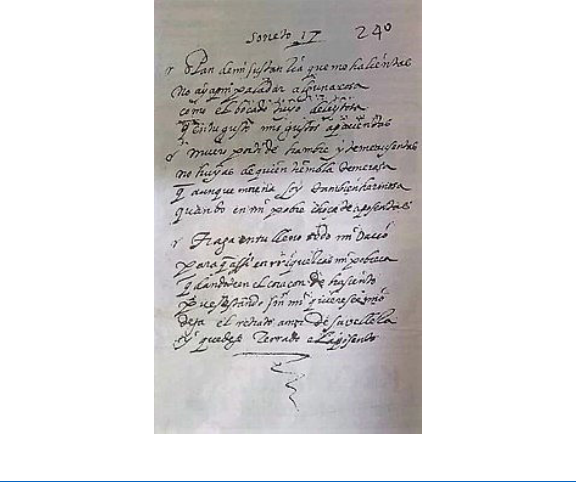

Fig. 1: Ana de la Trinidad, ‘Sonnet 17’ Source: Wikimedia commons

(

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Soneto_17_manuscrito.jpg)

Ana de Arellano y Navarra, born in 1577 to the family of the counts of Aguilar, was

destined for the life of a respectable Spanish noblewoman. Having received a humanist

education, excelling in mathematics, poetry, music, and Latin, she entered the Royal

Monastery of Herce, a Bernardine convent in the province of La Rioja. There, she

discovered the religious reforms begun by Teresa of Ávila (1505–1582) and Juan de la Cruz

(1542–1591), who sought to bring to their own Carmelite order a stricter rule of life and a

revival of Catholic mysticism. Ana, drawn to join their movement, and against her

parents’ wishes, staged a nocturnal escape to enter the newly founded discalced Carmelite

monastery at Calahorra, some twenty miles away. There, she came under the tutelage of

another educated woman and writer, Cecilia del Nacimiento, who acted as her mistress

of novices and prioress. From Calahorra, Ana (now Ana de la Trinidad) became engaged

in the Carmelite reform movement, corresponding with some of its most significant

figures, including the provincial superior, fray Antonio Sobrino, and the renowned

spiritual advisor, Tomás de Jesús. She also employed her literary talents to communicate

the mystical experience of union with God in poetry, inspired both by Cecilia and by their

Carmelite forbears, Teresa and Juan, both of whom had left extensive collections of poetry.

Much of Ana’s imagery is drawn from the tropes of mystical literature, each with their

symbolic significance.

Ana continually suffered from poor health, and died from tuberculosis on 2 April 1613,

aged 36. On her deathbed, Ana ordered that all her poetry be burnt. However, a copy of

19 sonnets had already been taken by Cecilia and kept at her convent in Valladolid. Since

these were copied in Cecilia’s hand, and kept among papers that included her own poetry,

they were attributed to Cecilia. More recently, however, a second manuscript was found

in which Cecilia affirms that the poems were Ana’s work. Many editions and studies still

attribute the poems to Cecilia, which is reflected in the bibliography below.

29

17. ‘Entre tantas saetas con que llaga’ (Sonnet 1)

1

Here, Ana develops the mystical image of the soul being pierced by the love of God, which

overcomes all worldly fortunes. Drawing on the language of courtly love, she describes

the experience as one of simultaneous pleasure and pain.

Entre tantas saetas con que llaga

mi corazón fortuna, que no queda

2

lugar do nueva herida le suceda,

3

hace la del amor sensible llaga.

4

Salud no busca el alma, que aunque haga 5

por sanar de sus males cuanto pueda,

tan dulce es el dolor que en ésta queda

5

que aposta se la rompe y se la estraga.

6

Mas tan secreta está que no parece

y el mismo amor la va desconociendo, 10

resurtiéndola el tiro juntamente.

7

Fortuna, suspendida en esta fuente,

8

mira correr mi llanto, atribuyendo

a Dios la causa, y no se ensoberbece.

9

18. ‘¡Oh peregrino, bien del alma mía…!’ (Sonnet 4)

Ana expresses the paradoxical joy of mystical union with Christ, experienced through a

process of kenosis, or self-emptying. The flame of Christ’s love both guides and purges her

desires; as he died and was resurrected, so his love will consume and renew her.

1

Poems are taken from Tomás Álvarez, ’19 sonetos de una poetisa desconocida. La Carmelita Ana de la

Trinidad del Carmelo de Calahorra’, Monte Carmelo 2 (1991), 241–272

2

fortuna: used here in the sense of ‘fate’. Unlike fortune, which is capricious, the love of God causes pain but

is ultimately healing.

3

do: poetic form of ‘donde’.

4

This line is an instance of hyperbaton: ‘hace la [saeta] del amor sensible llaga’. The image of the piercing of

the heart evokes Teresa of Ávila’s account of her transverberation, in which her heart was pierced by a ‘dart

of love’ (‘saeta de amor’) held by an angel: ‘V

eía un ángel cabe mí hacia el lado izquierdo, en forma corporal…

No era grande sino pequeño, hermoso mucho, el rostro tan encendido, que parecía de los ángeles muy

subidos … Veíale en las manos un dardo de oro largo, y al fin del hierro me parecía tener un poco de fuego.

Éste me parecía meter por el corazón algunas veces y que me llegaba a las entrañas; al sacarle, me parecía

consigo y me dejaba toda abrasada en amor grande de Dios’

(Vida, ch. 19).

5

esta = el alma;

6

aposta: ‘deliberately’; estraga: ‘arruinar, destruir, echar a perder, dañar y causar ruina y perjuicio’ (Auts.).

The subject of this line is, as in l.7, ‘el dolor’.

7

resurtiéndole (resurtir): ‘Dicho de un cuerpo: retroceder de resultas de un choque con otro’ (RAE).

8

suspendido: ‘vale también detener, o parar por algún tiempo’ (Auts.)

9

ensoberbecer: from soberbia (‘pride’), ‘to make proud’. The victory of humility over pride was seen by the

mystics, including Teresa of Ávila, as the hallmark of true Christian spirituality.

30

¡Oh peregrino, bien del alma mía,

10

que solo, sin resabios ni recelos

puedes matar mi sed, quitar mis duelos

y convertir mi llanto en alegría!

11

Pues, eres tú mi luz, mi guarda y guía

12

5

que tengo yo en la tierra ni en los cielos,

13

no quiero medios, no quiero consuelos,

fuera de ti de todo me desvía.

En soledad, de todo enajenada,

desnuda de mi ser y de mi vida, 10

para ser como fénix renovada,

14

en tu amorosa llama y encendida

me arrojo, que si fuere allí quemada,

seré cual salamandra renacida.

15

Select bibliography

NB:

† Indicates secondary literature that attributes Ana’s sonnets to Cecilia del Nacimiento.

The study of the sonnets themselves may nonetheless be helpful.

† Cecilia del Nacimiento, Obras completas de Cecilia del Nacimiento, ed. José Díaz Cerón

(Madrid: Editorial de Espiritualidad, 1970)

† ------Journeys of a Mystic Soul in Poetry and Prose, ed. and trans. by Kevin Donnelly and

Sandra Sider (Toronto: Iter, 2012) [N.B: The introduction to this volume is

helpful, but the translations themselves contain errors and misreadings]

Acereda Extremiana, Alberto, ‘Expresión poética y anhelo divino en Ana de la Trinidad’,

Kalakorikos 3 (1998) 59-71

Álvarez, Tomás, ’19 sonetos de una poetisa desconocida. La Carmelita Ana de la

Trinidad del Carmelo de Calahorra’, Monte Carmelo 2 (1991), 241–272

Cáseda Teresa, Jesús Fernando, Dolor humano, pasión divina (Logroño: Los Aciertos, 2020)

------'La poesía mística de Sor Ana de la Trinidad’, Kalakorikos 1 (1996), 85-94

Marcos Sánchez, Mercedes, Un mar de sed donde me anego: la obra poética de Ana de la

Trinidad (Burgos: Editorial de Espiritualidad, 2022)

10

Díaz Cerón (and other editions) read this as ‘hiende el alma mía’ (‘split (in the sense of wounding) my soul

in two’)

11

A reference to Psalm 29.12 [30.11] ‘Thou hast turned for me my mourning into joy’ (Douay Rheims).

12

See San Juan de la Cruz, Noche oscura del alma, ‘ni yo miraba cosa, sin otra luz y guía, sino la que en el

corazón ardía’ (ll.13–15).

13

A reference to the Lord’s Prayer (Pater noster) ‘sicut in cælo, et in terra’ (‘on earth as it is in heaven’).

14

fénix: The phoenix was said to die in flames and to rise reborn from its own ashes. In Christian imagery,

the phoenix symbolises the resurrection of Christ and the immortality of the human soul.

15

salamandra: In this period, salamanders were thought to be unaffected by fire.

31

† Olivares, Julián and Elizabeth Boyce, ‘Las madres Cecilia del Nacimiento y María de

San Alberto’ in their Tras el espejo la musa escribe: Lírica femenina de los Siglos de Oro

(Madrid: Siglo XXI de España, second edition, 2012), pp.271-88

Schlau, Stacey, ‘A Nest for the Soul: The Trope of Solitude in Three Early Modern

Discalced Carmelite Nun-Poets’ Scripta 7 (2016), 132-149

32