Bill de Blasio, Mayor

Carmelyn P. Malalis, Chair and Commissioner

NYC.gov/HumanRights

@NYCCHR

Central Office Address:

22 Reade Street

New York, NY 10007

July 2020

NYC Commission on Human Rights

Legal Enforcement Guidance on

Employment Discrimination on the Basis of Age

I. Introduction

Age discrimination in the workplace is an undeniable reality. Stereotypes about age,

whether about being “too old” or “too young,” permeate employment spaces. It is

particularly insidious because much of age discrimination stems from biases entrenched

in and perpetuated through media, caricatures, paternalistic assumptions, and more.

Compounding the problem, “[h]istorically, Congress, the courts, and society have

viewed age discrimination as less malevolent than race, gender, and other forms of

discrimination. Workplace age issues are perceived more as economic issues and not

as fundamental civil rights issues.”

1

Age discrimination is often more acute for certain

populations of workers because of intersecting discrimination related to their race,

2

gender (including gender identity),

3

immigration status,

4

and other protected categories.

Older workers are particularly at risk of being pushed out of long-term positions.

5

They

report that treatment at the workplace begins to deteriorate around age fifty, often

contributing to decisions to retire earlier than planned.

6

Additionally, older workers are

more likely to be laid off, and once out of a job, studies show that this same age group

is much more likely to remain unemployed or under-employed than younger workers.

7

The COVID-19 pandemic is also likely to exacerbate existing obstacles for older

workers, increasing their vulnerability to layoffs and creating additional barriers to

1

Laurie A. McCann, When Will the ADEA Become a “Real” Civil Rights Statute? 33 A.B.A. J. OF

LAB. & EMP. L. 89, 95 (2018).

2

Nicole Delaney & Joanna N. Lahey, The ADEA at the Intersection of Age and Race, 40 BERKELEY

J. EMP. & LAB. L. 61, 62 (2019).

3

See Shaleen Morales Saldarriaga, Flaming Fifties and Beyond: An International Comparison of

Age Discrimination Laws and How the United States Could Improve the Laws for Elderly Women, 25

ELDER L.J. 101, 102–03 (2017); see also Joanne Song McLaughlin, Limited Legal Recourse for Older

Women’s Intersectional Discrimination Under the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, 26 E

LDER L.J.

287, 288–92 (2019).

4

See Angely Mercado, Dynamics of Race, Poverty Deepen the Challenges of NYC’s Aging

Population, C

ITY LIMITS (Apr. 26, 2019), https://citylimits.org/2019/04/26/dynamics-of-race-poverty-

deepen-the-challenges-of-nycs-aging-population-brings/.

5

Peter Gosselin, If You’re Over 50, Chances Are the Decision to Leave a Job Won’t be Yours, PRO

PUBLICA (Dec. 28, 2018, 5:00 AM), https://www.propublica.org/article/older-workers-united-states-pushed-

out-of-work-forced-retirement.

6

See id.

7

See Patricia Cohen, New Evidence of Age Bias in Hiring, and a Push to Fight It, N.Y. TIMES, June

7, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/07/business/economy/age-discrimination-jobs-hiring.html

; see

also Kenneth Terell, Age Discrimination Goes Online, AARP (Nov. 7, 2017),

https://www.aarp.org/work/working-at-50-plus/info-2017/age-discrimination-online-fd.html (one study

found that older applicants for jobs, who demonstrated the same skill set as younger employees, received

significantly fewer callbacks that younger employees).

2

finding employment.

8

As of April 2020, unemployment rates for workers fifty-five and

older jumped from 3.3% to 13.6%.

9

Age discrimination also impacts younger workers. One survey found that employers can

be reluctant to hire people under thirty because they perceive younger workers to be

“unpredictable” and believe “‘they don’t know how to work.’”

10

Further, during times of

financial instability, for example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, younger workers have

been particularly vulnerable to layoffs;

11

specifically, 48% of young adult workers

between ages sixteen and twenty-four were employed in heavily-impacted industries,

such as restaurants, coffee shops, and gyms, as compared to 24% of workers overall.

12

Since 1977, the New York City Human Rights Law (“NYCHRL”) has included

protections against age discrimination for all workers,

13

regardless of one’s age, unlike

federal law that only protects older workers who are at least the age of forty.

14

The

NYCHRL prohibits discrimination on the basis of actual or perceived age by most

employers,

15

housing providers,

16

and providers of public accommodations in New York

8

See Aida Farmand & Teresa Ghilarducci, Older Workers Are Underrepresented in “Safe” Jobs in

the COVID-19 Recession, A

MERICAN SOCIETY ON AGING, https://www.asaging.org/blog/older-workers-are-

underrepresented-safe-jobs-covid-19-recession (last accessed June 23, 2020).

9

Employment Data Digest, April 2020, AARP PUB. POL’Y INST. 1 (May 8, 2020),

https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/ppi/2020/05/april-data-digest.pdf

.

10

Caroline Beaton, Too Young To Lead? When Youth Works Against You, FORBES, (Nov. 11,

2016),

https://www.forbes.com/sites/carolinebeaton/2016/11/11/too-young-to-lead-when-youth-works-

against-you/#71d78fad3c2a (citing Scott Wooldridge, Millennials: The New Victims of Age

Discrimination?, BENEFITSPRO (Sept. 30, 2015; 8:17 AM),

http://www.benefitspro.com/2015/09/30/millennials-the-new-victims-of-age-discrimination).

11

Taylor Nicole Rogers, Gen Z Is Going to Get Slammed Even Worse than Boomers by

Coronavirus Layoffs, B

USINESS INSIDER (Mar. 26, 2020),

https://www.businessinsider.com/harris-poll-gen-z-more-likely-laid-off-over-coronavirus-2020-3

.

12

Rakesh Kochhar, Hispanic Women, Immigrants, Young Adults, Those with Less Education Hit

Hardest by COVID-19 Job Losses, P

EW RESEARCH CENTER (June 9, 2020),

https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/06/09/hispanic-women-immigrants-young-adults-those-with-

less-education-hit-hardest-by-covid-19-job-losses/.

13

See Marta B. Varela, The First Forty Years of the Commission on Human Rights, 23 FORDHAM

URB. L. J. 983, 987 (1996); N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(1).

14

29 U.S.C.A. § 631(a).

15

In the employment context, the NYCHRL covers entities including employers, labor organizations,

or employment agencies, or any employee or agent thereof. N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(1). Under the

NYCHRL:

[T]he term “employer” does not include any employer that has fewer than four persons in

the employ of such employer at all times during the period beginning twelve months before

the start of an unlawful discriminatory practice and continuing through the end of such

unlawful discriminatory practice . . . [N]atural persons working as independent contractors

in furtherance of an employer's business enterprise shall be counted as persons in the

employ of such employer . . ..

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-102.

16

The NYCHRL prohibits unlawful discriminatory practices in housing, and covers entities including

the “owner, lessor, lessee, sublessee, assignee, or managing agent of, or other person having the right to

sell, rent or lease or approve the sale, rental or lease of a housing accommodation, constructed or to be

constructed, or an interest therein, or any agent or employee thereof.” N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(5).

3

City.

17

The NYCHRL also prohibits discriminatory harassment

18

and bias-based profiling

by law enforcement because of actual or perceived age.

19

Pursuant to Local Law No. 85

(2005), the NYCHRL must be construed “independently from similar or identical

provisions of New York state or federal statutes,” such that “similarly worded provisions

of federal and state civil rights laws [are] a floor below which the [NYCHRL] cannot fall,

rather than a ceiling above which the local law cannot rise.”

20

Any exemptions to the

NYCHRL must be construed “narrowly in order to maximize deterrence of discriminatory

conduct.”

21

The New York City Commission on Human Rights (the “Commission”) is the City

agency charged with enforcing the NYCHRL. Individuals interested in pursuing their

rights under the NYCHRL can choose to either file a complaint with the Commission’s

Law Enforcement Bureau within one (1) year of the alleged discriminatory act and within

three (3) years for claims of gender-based harassment,

22

or to file a complaint in state

or federal court within three (3) years of the alleged discriminatory act.

23

The protections

of the NYCHRL related to employment apply to all employees, freelancers, independent

contractors, and interns (whether paid or unpaid).

24

Covered entities also include real estate brokers, real estate salespersons, or employees or agents

thereof. Id. The NYCHRL defines the term “housing accommodation” to include “any building, structure or

portion thereof that is used or occupied or is intended, arranged or designed to be used or occupied, as

the home, residence or sleeping place of one or more human beings. Except as otherwise specifically

provided, such term includes a publicly-assisted housing accommodation.” N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-102.

However, the NYCHRL exempts from coverage:

(1) [ ] the rental of a housing accommodation, other than a publicly-assisted housing

accommodation, in a building which contains housing accommodations for not more than

two families living independently of each other, if the owner [or] members of the owner’s

family reside in one of such housing accommodations, and if the available housing

accommodation has not been publicly advertised, listed, or otherwise offered to the general

public; or (2) [ ] the rental of a room or rooms in a housing accommodation, other than a

publicly-assisted housing accommodation, if such rental is by the occupant of the housing

accommodation or by the owner of the housing accommodation and the owner or members

of the owner’s family reside in such housing accommodation.

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(5)(a)(4).

17

The NYCHRL prohibits unlawful discriminatory practices in public accommodations and covers

entities including any person who is the owner, franchisor, franchisee, lessor, lessee, proprietor,

manager, superintendent, agent or employee of any place or provider of public accommodation. N.Y.C.

Admin. Code § 8-107(4).

18

N.Y.C. Admin. Code §§ 8-602–603.

19

Id. § 14-151.

20

Local Law No. 85 § 1 (2005); N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-130(a) (“The provisions of this title shall be

construed liberally for the accomplishment of the uniquely broad and remedial purposes thereof,

regardless of whether federal or New York state civil and human rights laws, including those laws with

provisions worded comparably to provisions of this title, have been so construed.”).

21

Local Law No. 35 § 2 (2016); N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-130(b).

22

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-109(e).

23

Id. § 8-402.

24

Id. § 8-107(23).

4

This document serves as the Commission’s legal enforcement guidance on the

NYCHRL’s protections against employment discrimination based on actual or perceived

age. The NYCHRL is uniquely broad and reflective of New York City’s commitment to

eliminate all forms of discrimination,

25

offering more protections against age

discrimination in the workplace than its state or federal analogues. For instance, the

federal Age Discrimination in Employment Act (“ADEA”) has a minimum age

requirement of forty to file a claim,

26

permits preferential treatment for older workers in

certain circumstances,

27

and does not permit mixed-motive claims.

28

By contrast, the

NYCHRL imposes no age restriction and permits mixed-motive claims.

29

For an in-

depth, side-by-side comparison of the NYCHRL and the ADEA, as well as New York

State law, please see the Appendix at the end of this document.

30

This document is not

intended to serve as an exhaustive description of all forms of age-related claims of

employment discrimination under the NYCHRL.

II. Prohibitions on Age Discrimination in Employment Under the NYCHRL

Age discrimination in employment can manifest as disparate treatment, disparate

impact, and/or retaliation. An individual may present a claim of disparate treatment if

they are subject to discrimination “in compensation or in terms, conditions or privileges

of employment” because of their actual or perceived age.

31

To establish disparate

treatment, an individual must show that they were treated less well or subjected to an

adverse action motivated, at least in part, by discriminatory animus.

32

An individual may

demonstrate this through direct evidence of discrimination or indirect evidence that

gives rise to an inference of discrimination.

33

25

See Williams v. N.Y.C. Hous. Auth., 61 A.D.3d 62, 66–68 (1st Dep’t 2009).

26

29 U.S.C.A. § 631(a).

27

Gen. Dynamics Land Sys., Inc. v. Cline, 540 U.S. 581, 600 (2004) (finding the ADEA does not

prevent “an employer from favoring an older employee over a younger one”). By comparison, because

the NYCHRL protects workers of all ages from age discrimination, it generally does not permit favoring an

older employer over a younger one.

28

While courts have found that “mixed-motive” claims are not viable for most claims under the

ADEA, and that ADEA plaintiffs must show that age was the “but-for cause” of the challenged adverse

employment action to prevail on their age discrimination claim, Gross v. FBL Fin. Servs. Inc., 557 U.S.

167, 176–77 (2009), the standard for liability under the NYCHRL is whether age discrimination played any

role, in whole or in part, in the employer’s motivation, Melman v. Montefiore Med. Ctr., 98 A.D.3d 107, 128

(1st Dep’t 2012).

29

See Williams, 61 A.D.3d at 78, n.27 (for mixed-motive claims, “the question on summary

judgment is whether there exist triable issues of fact that discrimination was one of the motivating factors

for the defendant's conduct. Under Administrative Code § 8-101, discrimination shall play no role in

decisions relating to employment, housing or public accommodations.”).

30

While this document focuses on the NYCHRL, the Commission cites to federal authority where

instructive and for reasons of comparison. This document does not constitute legal enforcement guidance

of federal law.

31

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(1)(a)(3).

32

See Williams, 61 A.D.3d at 78.

33

Examples of direct evidence could include explicit statements by a covered entity that an adverse

action was based on a protected status, or explicitly discriminatory policies. See In re Comm’n on Human

Rights ex rel. Stamm v. E&E Bagels, OATH Index No. 803/14, Comm’n Dec. & Order, 2016 WL 1644879,

at *4 (Apr. 21, 2016). If plaintiff makes a prima facie showing of discrimination based on indirect evidence,

5

It is unlawful for an employer to have a neutral policy that has a disparate impact on

older workers, job applicants, or potential job applicants.

34

To show that a policy has a

disparate impact, an individual must demonstrate that an employer covered by the

NYCHRL has “a policy or practice . . . or a group of policies or practices . . . [that]

result[] in a disparate impact to the detriment of” individuals based on age.

35

An

employer has an affirmative defense if the “policy or practice bears a significant

relationship to a significant business objective[;]” however, if the complainant can show

that other practices would serve the business objective as well, the defense will fail.

36

Stereotypes and assumptions about age are at the root of most discriminatory practices

outlined below. One such pervasive belief is that age predicts overall ability, such as

physical or cognitive capacity to perform a job.

37

Unfounded age-related judgments

regarding ability are insidious in our society and must not be used as pretext for

unlawful discriminatory decisions in employment. In fact, decades of social science

research document that age does not predict one’s ability, performance, or

intelligence.

38

On the contrary, having an intergenerational workforce has been shown

to increase productivity and promote general wellbeing in the workplace.

39

From

then the burden shifts to the employer to rebut the presumption of discrimination by demonstrating that

there was a legitimate and non-discriminatory reason for its employment decision. Id. If the employer

articulates a legitimate, non-discriminatory basis for its decision, then the burden shifts back to the plaintiff

“to prove that the legitimate reasons proffered by defendant were merely a pretext for discrimination.”

Ferrante v. Am. Lung Ass’n, 90 N.Y.2d 623, 629–30 (1997). See Texas Dep’t of Cmty. Affairs v. Burdine,

450 U.S. 248, 253 (1981); Fields v. Dep’t of Educ. of New York, No. 154283/2016, 2019 WL 1580151

(Sup. Ct. N.Y. Cty. Apr. 12, 2019).

34

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(17).

35

Id.

36

Id.; see Teasdale v. N.Y.C. Fire Dep’t, FDNY, 574 F. App’x 50, 52 (2d Cir. 2014).

37

See generally Steven J. Kaminshine, The Cost of Older Workers, Disparate Impact, and the Age

Discrimination in Employment Act, 42 F

LA. L. REV. 229 (1990).

38

Victoria A. Lipnic, The State of Age Discrimination and Older Workers in the U.S. 50 Years After

the Age Discrimination in Employment Act, U.S.

EQUAL EMP’T OPPORTUNITY COMM’N, § IV(A)(1) & n.132

(2018) (citing several studies) (internal citations omitted); see K. Warner Schaie, The Longitudinal Study:

A 21-year Exploration of Psychometric Intelligence in Adulthood,” L

ONGITUDINAL STUDIES OF ADULT

PSYCHOLOGICAL DEVELOPMENT, 33 (K.W. Schaie, ed., 1983); Glen M. McEvoy & Wayne F. Cascio,

Cumulative Evidence of the Relationship between Employee Age and Job Performance, 74 J.

OF APPL.

PSYCH. 11 (1989) (finding age bears no relationship to employee performance); Ursula M. Staudinger,

Steven W. Cornelius & Paul B. Baltes, The Aging of Intelligence: Potential and Limits, 503 A

NNALS OF THE

AM. ACAD. OF POL. AND SOC. SCI., 43, 46 (1989) (“[P]ersons of the same chronological age are not

identical as to their mental status. There are 70-year-olds who function like 30-year-olds and vice versa.”);

Diane B. Howelson, Cognitive Skills and the Aging Brain: What to Expect,

DANA FOUNDATION: CEREBRUM

(Dec. 1, 2015), https://www.dana.org/article/cognitive-skills-and-the-aging-brain-what-to-expect/

.

39

See Wes Gay, Why A Multigenerational Workforce Is A Competitive Advantage, FORBES (Oct. 20,

2017), https://www.forbes.com/sites/wesgay/2017/10/20/multigeneration-workforce/#7d93430f4bfd

; see

generally Dawn C. Carr & Justine A. Gunderson, The Third Age of Life: Leveraging the Mutual Benefits of

Intergenerational Engagement, 26.3 P

UB. POL’Y & AGING REP. 83 (2016),

https://academic.oup.com/ppar/article/26/3/83/2460877 (discussing intergenerational engagement,

incuding in the workplace and in other areas of life).

6

cognitive and creative functions

40

to physical capability,

41

ability varies considerably

from person to person regardless of age. Other common discriminatory stereotypes

about older workers may include assumptions about a lack of flexibility, absence of

energy, and incapacity to work as a “team player.”

42

Younger workers also face harmful

stereotypes; for instance, “millennials,” referring to people born between 1980 and

1996, and “Generation Z,” referring to people born between 1997 and 2012, are often

stigmatized as lazy, craving recognition, and lacking the loyalty to commit to one job for

a long period of time.

43

Such stereotypes, directed toward any age group, are harmful

and can fuel unlawful discriminatory behavior.

The sections below provide examples of violations of the NYCHRL based on age

discrimination in recruitment, hiring, terms and conditions of employment, layoffs,

termination, and retirement. The examples highlight instances of unlawful disparate

treatment based on age, as well as instances where “age-neutral” policies may have a

disparate impact on a particular age group.

A. Job Postings and Recruiting

Under the NYCHRL, employers may not directly or indirectly express an age limitation

in a job posting unless explicitly required under federal, state, or local law.

44

Job

postings should convey the required qualifications of the position without stating

implicitly or explicitly that younger candidates are preferred. Job postings must not

contain explicit language that communicates a preference based on age, and should

also avoid using language

45

that suggests that the job requires that someone be of a

particular age group. For example, job postings that explicitly seek “recent college

graduates” may suggest that only young adults will be considered, and may exclude

40

Diane B. Howelson, Cognitive Skills and the Aging Brain: What to Expect, DANA FOUNDATION:

CEREBRUM (Dec. 1, 2015), https://www.dana.org/article/cognitive-skills-and-the-aging-brain-what-to-

expect/.

41

Glen P. Kenny, Herbert Groeller, Ryan McGinn, & Andreas D. Flouris, Age, Human Performance,

and Physical Employment Standards, 41 A

PPLIED PHYSIOLOGY, NUTRITION, AND METABOLISM S92 (2016).

42

See Cathy Ventrell-Monses, It’s Unlawful Age Discrimination—Not the “Natural Order” of the

Workplace!, 40

BERKELEY J. EMP. & LAB. L. 91, 96–98, 100–06 (2019).

43

See Siobhan Kelley, Jessica Perry & Julie Totten, Optimizing Generational Differences, 34.3 ACC

Docket, Apr. 2016, at 60, 63; Aisha Gani, Millennials at Work: Five Stereotypes – and Why They Are

(Mostly) Wrong, T

HE GUARDIAN (Mar. 15, 2016),

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/mar/15/millennials-work-five-stereotypes-generation-y-jobs

;

Mark C. Perna, Surprise—Millennial And Gen-Z Workers Are More Loyal Than You Think, FORBES (Mar.

3, 2020),

https://www.forbes.com/sites/markcperna/2020/03/03/surprisemillennial-and-gen-z-workers-are-

more-loyal-than-you-think/#3f8e27771df1.

44

Such permissible age limitations include, but are not limited to, the prohibition on individuals

under eighteen years old from serving alcohol (N.Y. A

LCO. BEV. CONT. LAW § 100 (McKinney 2020)) and

the general requirement that a worker be at least fourteen years old to be employed in most jobs in New

York State. N.Y. L

AB. LAW §§ 130, 131, 132. See also N.Y. CIV. SERV. LAW § 58 (prohibiting police officers

from being “less than twenty years of age as of the date of appointment nor more than thirty-five years of

age as of the date when the applicant takes the written examination”).

45

See Ann Brenoff, 5 Ageist Phrases to be Aware Of, AARP (June 12, 2019),

https://www.aarp.org/disrupt-aging/stories/info-2019/ageist-phrases.html

.

7

older qualified candidates who are interested in an entry-level position.

46

While it is

permissible for employers to recruit among college students or recent college

graduates, they must not restrict the applicant pool based on age and must ensure that

all applicants are assessed on their qualifications, regardless of age or potentially age-

related factors, such as year of graduation.

47

In addition, placing a cap on job

experience in job postings to a certain number of years suggests the employer will not

consider applicants who are older and have more years of experience, and may

discourage more experienced applicants from applying.

Characterizing certain necessary skills or traits in a way that is likely to discourage

applicants of a certain age group from applying may expose an employer to liability

under the NYCHRL.

48

For example, phrases such as “youthful energy” and “fresh-

minded” may suggest a preference for a younger applicant and dissuade older workers

from applying. In addition, expressing a preference for “digital natives”—which refers to

people who became comfortable using technology at an early age and who typically

were born after 1980

49

—suggests an impermissible limit based on age, and may

indicate an unlawful discriminatory motivation to hire younger people. As an alternative,

employers should frame job qualifications in an age-neutral way; for instance, for a

technology-related position, a job posting could list specific skills, such as familiarity with

a particular software or program that is necessary to the job, and assess candidates

based on their abilities to perform those skills.

Fellowships or training programs may permissibly limit the level of experience for

applicants, by, for example, stating that applicants have zero to two years of

experience, where the fellowships and programs are: intended to be term-limited; are

focused on bringing new entrants into the field; and include training and mentorship as a

46

U.S. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n, Prohibited Employment Policies/Practices,

https://www.eeoc.gov/prohibited-employment-policiespractices (“It is illegal for an employer to publish a

job advertisement that shows a preference for or discourages someone from applying for a job because

of his or her . . . age . . .. For example, a help-wanted ad that seeks . . . ‘recent college graduates’ may

discourage . . . people over 40 from applying and may violate the law.”).

47

See 29 C.F.R. § 1625.4(a), which states that advertisements for “recent college graduate[s]”

discriminate against older persons, unless an ADEA exception applies. See also Magnello v. TJX

Companies, Inc., 556 F. Supp. 2d 114, 123 (D. Conn. 2008). Recruiting preferences for “recent

graduates” have survived challenges under the ADEA. See, e.g., Mistretta v. Sandia Corp., 1977 WL 17

(D.N.M. Oct. 20 1977), aff'd sub nom. Equal Emp’t Opportunity Comm’n v. Sandia Corp., 639 F.2d 600

(10th Cir. 1980) (“There is nothing inherently suspicious about on-campus recruiting programs”;

engineering graduates have recent exposure to new techniques and are job hunting, so campus

recruiting gives effective access to available labor market).

48

See N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(1)(d).

49

The term digital native has a direct relationship to the age of an individual, since digital natives

are generally defined as those individuals who were born after 1980. “Digital native” does not connotate

an individual’s skill level or ability to use technology. See Digital Native (Sept. 19, 2012), T

ECHNOPEDIA,

https://www.techopedia.com/definition/28094/digital-native

; Kate Moran, Millennials as Digital Natives:

Myths and Realities, NIELSEN NORMAN GROUP (Jan. 3, 2016),

https://www.nngroup.com/articles/millennials-digital-natives/; see also Ann Brenoff, 5 Ageist Phrases to

be Aware Of, AARP (June 12, 2019), https://www.aarp.org/disrupt-aging/stories/info-2019/ageist-

phrases.html.

8

core component.

50

Despite the disparate impact that such programs may have based

on age, a covered entity may demonstrate the requisite “significant relationship to a

significant business objective” where the purpose of the program is to foster

professional development among new entrants into a field, build a pipeline of qualified

workers, and/or encourage workers to undertake less lucrative work in fields that may

be harder to break into.

51

Employers and other entities that administer such fellowships

and programs should be able to demonstrate how their fellowships and programs satisfy

a significant business objective, as they are subject to a disparate impact analysis under

the NYCHRL.

52

Examples of violations

• An employer uses an online screening algorithm that excludes older applicants

who report having more than ten years of experience because the employer

believes they will demand higher salaries than the employer is able to pay.

• A business posts an ad which says it is seeking an “energetic person who is a

cultural fit for a company of young entrepreneurs” and only invites applicants

under the age of thirty for interviews.

• A job posting requires that applicants have “no more than seven years of work

experience.”

B. Hiring

Age discrimination is arguably most pervasive in the hiring process.

53

It is a violation of

the NYCHRL for a covered “employer, employment agency, or labor organization” to

discriminate against job applicants based on their actual or perceived age.

54

A

discriminatory motive may be inferred where an employer unnecessarily inquires about

an applicant’s age.

55

It is a violation of the NYCHRL if age discrimination constitutes

even part of the employer’s motivation for denying a person employment.

56

In addition,

50

See, e.g., Neary v. Gruenberg, No. 16-CV-5551 (KBF), 2017 WL 4350582, at *3 (S.D.N.Y. July

26, 2017), aff'd, 730 F. App’x 7 (2d Cir. 2018) (“President Barack Obama . . . establish[ed] the ‘Pathways

Program’ to encourage recruitment of ‘students and recent graduates . . . as an ever-growing number of

Federal employees nears retirement age’ and to ‘clear paths to civil service careers for recent

graduates.’. . . Similar to the FDIC’s CEP, the [program] provides that to qualify for the Pathways

Program, applicants must have obtained a degree within the previous two years.”).

51

Cf. id. at 10 (affirming motion to dismiss age-related claim because government employer’s

proffered a rational basis for its hiring practices to replenish a workforce containing an “ever-growing

number of Federal employees near[ing] retirement age with students and recent graduates,” and forty-

one-year-old job applicant’s allegations were insufficient to give rise to inference of discriminatory motive).

52

See N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(17).

53

See Patricia Cohen, New Evidence of Age Bias in Hiring, and a Push to Fight It, N.Y. TIMES, June

7, 2017, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/07/business/economy/age-discrimination-jobs-hiring.html

.

54

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(1)(a)(2).

55

Date of birth may be requested when necessary to conduct background checks. It is a best

practice for employers to wait until after an offer is made to make such an inquiry.

56

Bennett, 92 A.D.3d at 39–41.

9

a hiring policy which disparately impacts older job applicants

57

based on job applicants’

actual or perceived age violates the NYCHRL.

58

Relying on inappropriate age-related factors and stereotypes to deny employment is a

violation of the NYCHRL. For example, employers should not exclude candidates on the

ground of “overqualification” for a position based on their years of work experience.

59

Indeed, doing so often “mask[s] the real reason for refusal, namely, in the eyes of the

employer the applicant is too old.”

60

If an employer is concerned that applicants with

more work experience might be bored by the position or dissatisfied with the

compensation, the best approach is to be clear about the responsibilities and

expectations for the job, as well as the level of compensation that is available and to let

the candidates decide for themselves whether the position is of genuine interest, rather

than to reject someone as overqualified. Employers also must not stereotype younger

applicants, for example, by relying on assumptions that younger workers will lack

sufficient commitment or loyalty to a job.

It may be a violation of the NYCHRL if an employer uses hiring policies or practices

which appear to be age-neutral and have a disparate impact on a particular age

group.

61

Application processes without structured interviews or consistently-applied

standards may expose employers to liability where such practices lead to a disparate

impact on applicants based on age. For example, if younger applicants are consistently

preferred over equally qualified older applicants and the employer uses unstructured

interviews and purely subjective criteria to evaluate candidates, it may constitute a

violation of the NYCHRL on the basis of age. Some element of subjectivity in hiring is

permitted, but just as “an employer may not use wholly subjective and unarticulated

standards to judge employee performance,”

62

it is also potentially unlawful where it has

a disparate impact on a protected category. Where job applicants of a particular age are

consistently chosen or rejected for certain job opportunities, employers should be

prepared to demonstrate non-discriminatory reasons for their selection.

57

In contrast, under federal law, the question of whether job applicants may benefit from a disparate

impact theory of liability pursuant to the ADEA is much less clear. See William Hrabe, Will You Still Need

Me, Will You Still Hire Me, When I'm Sixty-Four: Disparate Impact Claims and Job Applicants Under the

ADEA, 26 E

LDER L.J. 395, 405–09 (2019).

58

See N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(1).

59

See, e.g., Alexia Elejalde-Ruiz, Overqualified? Or Too Old? Age Discrimination Case Takes Aim

at Biased Recruiting Practices, C

HICAGO TRIBUNE, Sept. 28, 2018,

https://www.chicagotribune.com/business/ct-biz-age-discrimination-lawsuit-dale-kleber-0930-story.html

.

60

Taggart v. Time, Inc., 924 F.2d 43, 47 (2d Cir. 1991); see also Vaughn v. Mobil Oil Corp., 708 F.

Supp. 595, 601 (S.D.N.Y. 1989).

61

An assessment of liability would turn on whether the policy or practice bears a significant

relationship to a significant business objective. N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(17).

62

DeLuca v. Sirius XM Radio, Inc., No. 12-CV-8239 (CM), 2017 WL 3671038, at *15 (S.D.N.Y. Aug.

7, 2017) (quoting Knight v. Nassau Cty. Civil Serv. Comm’n, 649 F.2d 157, 161 (2d Cir. 1981)).

10

Examples of violations

• An interviewer asks applicants she perceives to be older, “How old are you?”

during their interviews and does not seriously consider anyone over the age of

forty-five.

• An interviewer tells a qualified applicant who is perceived to be younger than

thirty that they are looking for someone who is “committed to old-school values of

loyalty” and not just some “young, fly-by-night person who’s looking to make a

quick buck.”

• An employer requires graduation dates on its application for a position and has a

policy of only interviewing those who have graduated college in the last ten

years.

63

C. Discrimination During Employment: Disparate Treatment, Harassment

Disparate treatment includes being subjected to lesser terms or conditions of

employment, including denials of work opportunities, demotions, or unfavorable

scheduling because of a person’s age. Disparate treatment may manifest as

harassment when an employee is subjected to behavior that is demeaning, humiliating,

or offensive because of their age. Harassment covers a broad range of conduct.

64

The

severity or pervasiveness of the harassment is only relevant to damages.

65

Even an

employer’s single comment made in circumstances where that comment would signal

discriminatory views about one’s age may be enough to constitute harassment.

66

An

individual does not need to be the target of the harassment to feel its impact and have

legal recourse.

67

63

An employer requesting information such as date of birth, age, or graduation date on an

employment application form is not a per se violation of the law; however, because requests that

implicate age may suggest a limitation based on age, they will be closely examined to ensure they are

used for a permissible purpose and not a violation of the NYCHRL. Accord 29 C.F.R. § 1625.5.

64

An employer may assert the affirmative defense that the derogatory comment about the

individual’s age would be perceived as a petty slight or a trivial inconvenience by a reasonable person in

the complainant’s shoes. Williams, 61 A.D.3d at 79–80.

65

See Goffe v. NYU Hosp. Ctr., 201 F. Supp. 3d 337, 351 (E.D.N.Y. 2016) (“the federal severe or

pervasive standard of liability no longer applies to NYCHRL claims, and the severity or pervasiveness of

conduct is relevant only to the scope of damages”) (emphasis in original); Williams, 61 A.D.3d at 76.

66

See Cardenas v. Automatic Meter Reading Corp., OATH Index No. 1240/13, Comm’n Dec. &

Order, 2015 WL 7260567, at *8 (Oct. 28, 2015) aff’d sub nom. Automatic Meter Reading Corp. v. N.Y.C.,

63 Misc. 3d 1211(A) (Sup. Ct. N.Y. Cty. Feb. 28, 2019) (citing Williams, 61 A.D.3d at 80 n.30). Under

federal law, a single comment is not sufficient to allege a violation of the ADEA because discriminatory

comments based on age must be severe and pervasive in order to establish a claim for a hostile work

environment. See, e.g., Kassner v. 2nd Ave. Delicatessen, Inc., 496 F.3d 229, 240 (2d Cir. 2007) (several

ageist comments made by managers to older waitresses that they should “retire early,” “take off your wig,”

or “drop dead” was not enough to maintain a claim for a hostile work environment under the ADEA or Title

VII because the conduct was not considered severe or pervasive).

67

See Mihalik v. Credit Agricole Cheavreux N. Am., Inc., 715 F.3d 102, 113–15 (2d Cir. 2013);

Leibovitz v. N.Y.C. Transit Auth., 252 F.3d 179, 190 (2d Cir. 2001).

11

Employers are strictly liable where the harasser exercises managerial or supervisory

responsibility.

68

Employers are also strictly liable for a non-managerial employee’s

discriminatory conduct if the employer: (1) knew about the employee’s conduct and

“acquiesced in such conduct or failed to take immediate and appropriate corrective

action;”

69

or (2) should have known about the employee’s discriminatory conduct and

“failed to exercise reasonable diligence to prevent such discriminatory conduct.”

70

Examples of violations

• A manager frequently calls an independent contractor doing work on the

premises “old man,” “pops,” and “grandpa.”

• An employer denies training opportunities to an older worker that the worker

needs to complete in order to be considered for a promotion, explaining that

providing those opportunities would be “a waste of time and resources at your

age.” The employer provides those opportunities to a younger employee who is

subsequently promoted.

71

• A twenty-seven-year-old woman is regularly talked down to, has her ideas

dismissed in meetings by her supervisor, and is not given major projects despite

strong performance, while a colleague, who is a forty-five year old man, is not

subjected to the same treatment and is given increasing responsibilities.

72

• An employee in his sixties regularly endures inappropriate comments related to

his age by his coworker.

73

The employee tells his project manager, but the

manager says that the coworker is “only kidding” and takes no action.

• An employee has worked for a company for more than thirty years and is the

oldest person on her team. Despite receiving consistently positive performance

reviews, her new manager is giving her fewer projects and dividing up her

portfolio among her younger colleagues. When she asks her manager about the

change, he tells her he does not want to “overwhelm her with such a large

portfolio, given her age.”

• A supervisor consistently singles out the youngest member of his team, calling

him “kid” and “young blood” and yelling at him in front of his colleagues, “it’s time

for you to grow up and put your big boy pants on.”

D. Layoffs and Termination

It is unlawful for employers to terminate or lay off an employee if motivated at least in

part by their actual or perceived age.

74

Older workers are particularly vulnerable during

68

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(13)(b)(1).

69

Id. § 8-107(13)(b)(2).

70

Id. § 8-107(13)(b)(3).

71

See, e.g., Cross v. N.Y.C. Transit Auth., 417 F.3d 241, 250 (2d Cir. 2005).

72

This could be a claim of both age and gender discrimination.

73

See Dediol v. Best Chevrolet, Inc., 655 F.3d 435, 439–40 (5th Cir. 2011).

74

See N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(1)(a)(2); Weiss v. JPMorgan Chase & Co., No. 06 Civ.

4402(DLC), 2010 WL 114248, at *1 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 13, 2010) (“[T]he NYCHRL requires only that a plaintiff

prove that age was ‘a motivating factor’ for an adverse employment action.”); Williams, 61 A.D. 3d at 78 n.

12

employer layoffs.

75

It is a violation of the NYCHRL when employers disproportionately

lay off older workers if the employer does not have a legitimate non-discriminatory

reason for the staff reduction.

76

While corporate or organizational restructuring,

downsizing, and financial considerations, such as budgetary constraints, are often

legitimate business decisions,

77

they may not be used as a pretext for unlawful

discrimination based on age

78

and, moreover, employers should be mindful of the

potential disparate impact that such decisions may have on older workers.

79

Employers

should be able to show a legitimate business purpose for, for example, eliminating an

older worker’s specific position, or for engaging in lay-offs that disproportionately impact

workers over a certain age. Although replacing an older worker with a younger worker is

not on its own a violation of the NYCHRL, it could support a claim of age discrimination

against the terminated employee.

80

However, policies related to employee retention

based on seniority policies, such as in collective bargaining agreements, are generally

permissible.

81

Examples of violations

• During a company’s layoffs, only one poorly performing younger employee is laid

off, while everyone else who was laid off was an older employee with satisfactory

or excellent performance and there is no business justification for selecting the

older workers for layoff.

27 (“[u]nder Administrative Code § 8-101, discrimination shall play no role in decisions relating to

employment, housing or public accommodations”); see also Local Law No. 85 §§ 1, 7 (2005).

75

Kate Rockwood, Hiring in the Age of Ageism, SOC’Y FOR HUMAN RESOURCES MGMT. (Jan. 22,

2018), https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/0218/pages/hiring-in-the-age-of-ageism.aspx.

76

See, e.g., Kaiser v. Raoul’s Rest. Corp., 112 A.D.3d 426, 427 (1st Dep’t 2013).

77

See, e.g., Elfenbein v. Bronx Lebanon Hosp. Ctr., No. 08-CV-5382, 2009 WL 3459215, at *6

(S.D.N.Y. Oct. 27, 2009) (assessing whether hospital’s restructuring amounted to pretext for age

discrimination under the ADEA, NYCHRL, and NYSHRL); Matter of Laverack & Haines v. N.Y. State Div.

of Human Rights, 88 N.Y.2d 734, 738 (1996); Roundtree v. School Dist. of Niagara Falls, 294 A.D.2d 876,

877–78 (4th Dep’t 2002) (budget deficit required a workforce reduction); Genesky v. Local 1000, 287

A.D.2d 594, 594–95 (2d Dep't 2001) (the termination of the plaintiff's employment was in response to

budgetary constraints and thus not age discrimination).

78

See Carras v. MGS 782 Lex, Inc., 310 F. App’x 421, 423 (2d Cir. Dec. 19, 2008) (denying

defendant’s motion for summary judgment, concluding that there was a triable issue of fact as to whether

the employer’s cost-cutting rationale was pretext for age discrimination in violation of the ADEA,

NYCHRL, and NYSHRL, especially considering other employer behavior that may suggest discriminatory

animus).

79

See Bennett v. Time Warner Cable, Inc., 138 A.D.3d 598, 598–99 (1st Dep’t 2016) (denying

motion to dismiss disparate impact claim under the NYCHRL, in which plaintiffs challenged the

employer’s decision to eliminate general foreman position, which was generally held by workers in their

fifties and sixties).

80

This would be especially true where an employer unquestionably has a practice of replacing older

workers with younger workers. See Olivia Carville, IBM Fired as Many as 100,000 in Recent Years,

Lawsuit Shows, B

LOOMBERG (July 31, 2019), https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-07-31/ibm-

fired-as-many-as-100-000-in-recent-years-court-case-shows (“The company started firing older workers

and replacing them with millennials, who IBM’s consulting department said ‘are generally much more

innovative and receptive to technology than baby boomers.’”).

81

See generally Matter of Sauer v. Donaldson, 49 A.D.3d 656, 656–57 (2d Dep’t 2008); Brooks v.

Purcell, 131 A.D. 2d 620, 621–22 (2d Dep’t 1987); 53 N.Y. Jur. 2d E

MP’T REL. § 615.

13

• In a situation in which there is no statutorily mandated retirement age, after an

employee who is fifty-two is selected for a layoff, a supervisor tells them, “We

want someone that will give us another ten or so years.”

82

• An employee is repeatedly told they are getting “too old for the job” and is fired

shortly thereafter.

• An older worker who consistently met expectations in their performance reviews

is terminated for lacking “twenty-first century skills” by a supervisor who, at an all-

staff meeting, praised the superior technological ability of younger workers

because “they were born into a world of technology.”

83

• A new supervisor comments that an older employee “reminds me of my

grandma, who can be difficult” and terminates her a week later for a series of late

arrivals and absences, but does not discipline any of the younger, less

experienced workers for similar late arrivals and absences.

84

• A younger worker whose work output exceeds that of her colleagues is laid off

after her supervisor explained that he “just can’t relate to millennials” and he

preferred to keep on someone who is a better “generational fit” for the team.

E. Retirement

It is unlawful under the NYCHRL for an employer to force an employee to retire at a

specific age,

85

unless there is a legally mandated retirement age.

86

Mandatory

retirement ages violate the NYCHRL because such policies treat workers less well

based on their age and are premised on discriminatory stereotypes about older workers’

ability or desire to continue working. Similarly, taking a worker’s age into account when

considering whether to renew their employment contract is impermissible under the

NYCHRL.

87

82

See Sharp v. Acker Plant Servs. Grp., Inc., 726 F.3d 789, 794 (6th Cir. 2013).

83

See, e.g., Marlow v. Chesterfield Cty. Sch. Bd., 749 F. Supp. 2d 417, 421 (E.D. Va. 2010)

(holding there was a genuine issue of material fact as to whether an employer harbored age bias against

plaintiff where an employer made comments that plaintiff lacked twenty-first century skills and referred to

“digital natives” born when particular technology existed versus older “digital immigrants” with “thick

accents”).

84

See, e.g., Gorzynski v. JetBlue Airways Corp., 596 F.3d 93, 98 (2d Cir. 2010) (holding defendant

employer enforced rules and disciplined employees in a discriminatory way toward older workers).

85

See, e.g., Comm’n on Human Rights ex rel. Joo v. UBM Bldg. Maint. Inc., OATH Index No.

384/16, 2018 WL 6978286 (Dec. 20, 2018) (finding respondent liable for forcing complainant to retire at

sixty-five pursuant to a policy of not employing people over sixty-five, where there was no applicable law

mandating retirement based on age).

86

For example, certain civil service positions, including public safety officers in the state and local

police force and fire department, have retirement ages which are mandated by law. N.Y. C

IV. SERV. LAW §

54 (McKinney 2020) (age requirements for civil service positions); N.Y. R

ETIRE. & SOC. SEC. LAW § 384

(retirement for police officers and firefighters); 29 U.S.C.A. § 623(j) (retirement for law enforcement

officers and firefighters).

87

See Delville v. Firmenich Inc., 920 F. Supp. 2d 446, 460 (S.D.N.Y. 2013).

14

Voluntary early retirement incentive programs (“ERIPs”)

88

that are consistent with the

Older Workers’ Benefit Protection Act’s (“OWBPA”) amendments to the ADEA are

permissible under the NYCHRL.

89

Under the OWBPA, an employer’s ERIP must be

voluntary and consistent with the purposes of the ADEA.

90

ERIPs that categorically

provide lesser benefits to older beneficiaries as compared to younger beneficiaries

violate the NYCHRL.

91

Examples of violations

• An employer tracks all contract employees’ ages and makes decisions about

whether to renew those employees’ contracts based on how soon the employer

thinks the employees intend to retire. The employer does not renew the contract

of any employees over the age of fifty, while renewing the contracts of

employees younger than fifty.

92

• A company has a policy requiring all employees to retire at sixty-five, when there

is no relevant legal mandatory retirement age.

93

• An employer has an ERIP with an age-based window defining benefits

dependent on age in which those retiring at age fifty-eight would have received

four years of incentive payments, those retiring at age sixty only two years of

payments, and those retiring at age sixty-two or later, nothing.

94

88

In an ERIP, “older employees typically are offered a financial incentive in exchange for their

agreement to leave the workforce earlier than they had planned.” U.S. EQUAL EMP’T OPPORTUNITY

COMM’N, EEOC COMPLIANCE MANUAL, DIRECTIVES TRANSMITTAL 915.003, CH. 3: BENEFITS, § VI(A) (2000),

https://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/benefits.html. Employers may benefit from this “since the older workers

who accept the incentive usually are the higher-paid individuals in the workforce” and “[t]he older

employees also benefit inasmuch as they are able to retire with larger benefits earlier than otherwise

would have been possible.” Id.

89

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(1)(e); see 29 U.S.C.A. § 623(f)(2)(B)(ii); Abrahamson v. Bd. of

Educ. of Wappingers Falls Cent. Sch. Dist., 374 F.3d 66, 74 (2d Cir. 2004); U.S.

EQUAL EMP’T

OPPORTUNITY COMM’N, EEOC COMPLIANCE MANUAL, DIRECTIVES TRANSMITTAL 915.003, CH. 3: BENEFITS, §

VI(A) (2000), https://www.eeoc.gov/policy/docs/benefits.html.

90

Workplace Flexibility 2010, Geo. Univ. L. Cent., Early Retirement Incentive Plans and the Age

Discrimination in Employment Act, M

EMOS AND FACT SHEETS 54, at 1–2 (2010) (citing 29 U.S.C. §

623(f)(2)(B)(ii)), https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/legal/54. Such explicit purposes are: “to promote

employment of older persons based on their ability rather than age; to prohibit arbitrary age discrimination

in employment; and to help employers and workers find ways of meeting problems arising from the impact

of age on employment.” 29 U.S.C.A. § 621(b).

91

See N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(1)(a)(3); see also Auerbach v. Bd. of Educ. of Harborfields

Cent. Sch. Dist. of Greenlawn, 136 F.3d 104, 114 (2d Cir. 1998) (discussing Karlen v. City Colleges of

Chicago, 837 F.2d 314 (7th Cir. 1988), in which an ERIP arbitrarily discriminated based on age by

offering lesser benefits to beneficiaries over age sixty-four than to younger beneficiaries); O'Brien v. Bd.

of Educ. of Deer Park Union Free Sch. Dist., 127 F. Supp. 2d 342, 350 (E.D.N.Y. 2001) (ERIPs “that

reduce the value of the retirement benefit as the putative retiree ages are impermissible”).

92

See, e.g., Delville, 920 F. Supp. 2d at 460.

93

See, e.g., Joo, 2018 WL 6978286, at *3–4.

94

Solon v. Gary Comty. Sch. Corp., 180 F.3d 844, 853 (7th Cir. 1999) (striking down discriminatory

ERIP where “[i]n this respect, employees who retire at a younger age are treated more favorably than

those who retire later, based not on years of service or some other nondiscriminatory factor, but solely on

their age at retirement.”).

15

F. Retaliation

A covered entity may not retaliate against an individual because they engaged in

protected activity. Protected activity includes: (1) opposing a discriminatory practice

prohibited by the NYCHRL;

95

(2) raising an internal complaint regarding a practice

prohibited under the NYCHRL; (3) filing a complaint with the Commission or any other

enforcement agency or court; or (4) testifying, assisting, or participating in an

investigation, proceeding or hearing related to an unlawful practice under the

NYCHRL.

96

In order to establish a prima facie claim for retaliation, an individual must

show that: the individual engaged in a protected activity; the covered entity was aware

of the activity; the individual suffered an adverse action; and there was a causal

connection between the protected activity and the adverse action.

97

When an individual

opposes what they believe in good faith to be unlawful discrimination, it is illegal to

retaliate against the individual, even if the underlying conduct they opposed is not

ultimately determined to violate the NYCHRL.

An action taken against an individual that is reasonably likely to deter them from

engaging in such activities is considered unlawful retaliation. The action need not rise to

the level of a final action or a materially adverse change to the terms and conditions of

employment to be retaliatory under the NYCHRL.

98

The action could be as severe as

demotion, removal of job responsibilities, or termination, but could also be less severe

such as relocating an employee to a less desirable part of the workspace, shifting an

employee’s schedule, or reducing their inclusion in group projects.

G. Remedies for Violations of the NYCHRL

Individuals who have been unlawfully discriminated against based on their age under

the NYCHRL are entitled to various kinds of compensatory damages, including back

pay, front pay, and damages for emotional distress.

99

In addition, punitive damages may

be available to plaintiffs who prevail on age discrimination claims in state court. In

administrative proceedings, a finding of an age discrimination violation may result in the

imposition of civil penalties, which are paid to the City,

100

and/or other affirmative relief,

95

The NYCHRL has more liberal retaliation protections than federal law. Under federal law,

retaliation must involve some kind of materially adverse change in the terms and conditions of

employment, while under the NYCHRL, retaliation can involve any act which would be reasonably likely to

deter a person from engaging in protected activity (e.g., changing the location of plaintiff's locker or

warning her about allegedly excessive use of sick days might not qualify as retaliation under the federal

law but might qualify under the NYCHRL). Selmanovic v. NYSE Grp., Inc., No. 06 Civ. 3046, 2007 WL

4563431, at *6 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 21, 2007).

96

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(7).

97

Id.; Selmanovic, 2007 WL 4563431, at *5.

98

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(7).

99

Id. § 8-126.

100

Damages and remedies under the ADEA are more limited than under the NYCHRL. Plaintiffs who

prevail on their ADEA claims are only able to receive back pay, promotion, and reinstatement of

employment, and, for willful violations of the law, liquidated damages. 29 U.S.C.A. § 626(b). Unlike under

the NYCHRL, claimants are not entitled to receive emotional distress damages.

16

such as restorative justice interventions, anti-discrimination training, and changes to

workplace policies.

101

III. Best Practices for Employers

To ensure that a workplace is free from age discrimination, employers should make

significant efforts to foster an intergenerational workforce. As best practices, employers

should:

• Avoid putting a maximum number of years of experience in a job posting, to

encourage all candidates to apply, including workers who may exceed the

requirement.

• Ensure that both externally and internally facing materials, including recruitment

materials, reflect the entity’s age diversity and do not exclusively target a specific

age group.

• Avoid hiring requirements that may have a disparate impact based on age, such

as requiring that a letter of recommendation be provided from a college

professor.

102

An employer should allow for letters of recommendation from

previous employers, co-workers, and others who have relevant knowledge of the

applicant’s skills.

• Require that employees and supervisors take implicit bias trainings related to age

discrimination.

• Eliminate job application questions that require birth dates or date of graduation,

as such practices may deter or disadvantage older applicants.

• Avoid terms in job descriptions that suggest a bias based on age, such as

“young,” “youthful energy,” “digital native” or “fresh-minded.” As an alternative,

consider words that reflect the job requirements in an age-neutral way.

103

• Include age in diversity and inclusion efforts in order to foster a multigenerational

workforce.

104

• Avoid exclusively recruiting applicants from campus job fairs and instead ensure

that recruitment is conducted in a way that captures a diversity of applicants,

including through posting on different job search websites, through community

job fairs, and through professional associations and networks.

• Invest in training and professional development to ensure all workers, including

older workers, are trained in relevant skills.

101

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-120(a).

102

Kate Rockwood, Hiring in the Age of Ageism, SOC’Y FOR HUMAN RESOURCES MGMT. (Jan. 22,

2018), https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/0218/pages/hiring-in-the-age-of-ageism.aspx.

103

See Insperity Staff, 6 Top Tips for Preventing Ageism in the Workplace, INSPERITY,

https://www.insperity.com/blog/preventing-age-discrimination/

(last accessed July 20, 2020).

104

One survey found that only 8% of employers’ diversity and inclusion strategies included the goal

of increasing age diversity. Lori A. Trawinski, Leveraging the value of an Age-Diverse Workforce, SHRM

F

OUNDATION, at 1, https://www.shrm.org/foundation/ourwork/initiatives/the-aging-

workforce/Documents/Age-Diverse%20Workforce%20Executive%20Briefing.pdf (last accessed July 20,

2020).

17

• Create and incorporate structured interviewing as a part of employer implicit bias

training.

• When offering voluntary buyouts during layoffs, avoid targeting employees based

on age, but instead offer buyouts in an age-neutral fashion and provide

transparency regarding the terms of the buyouts.

*******

The Commission is dedicated to eradicating workplace age discrimination in New York

City. If you believe you have been subjected to unlawful discrimination on the basis of

your actual or perceived age or membership in another protected class, please contact

the Commission at 311 or at (212) 416-0197 to file a complaint of discrimination with the

Commission’s Law Enforcement Bureau.

18

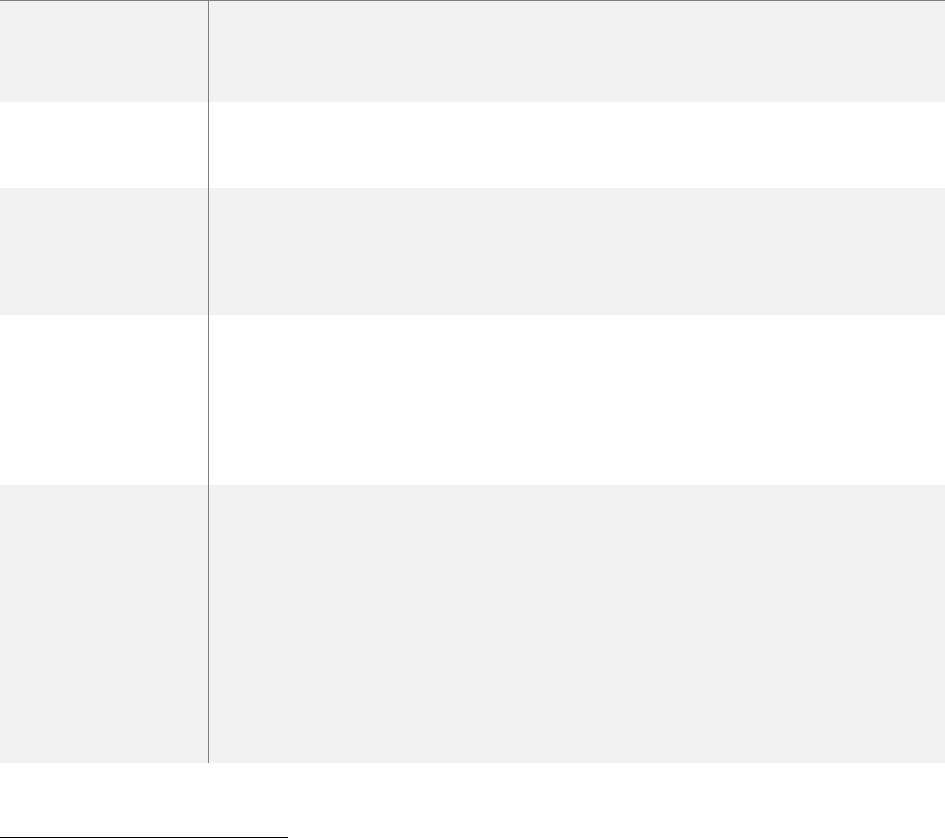

KEY DIFFERENCES BETWEEN FEDERAL, STATE, AND CITY AGE

DISCRIMINATION LAWS (AS OF JULY 2020).

STATUTE

Age

Discrimination in

Employment Act

(ADEA)

105

New York State

Human Rights Law

106

New York City

Human Rights Law

107

AGE

THRESHOLD

40 years old and

up

108

18 years old and up

109

No age limit

ECONOMIC

DAMAGES

(FRONT PAY

AND BACK PAY)

Available

110

Available

111

Available

112

COMPENSATORY

DAMAGES FOR

EMOTIONAL

DISTRESS OR

PAIN AND

SUFFERING

Not available

113

Available; no statutory

cap

114

Available; no statutory

cap

115

PUNITIVE

DAMAGES

Liquidated

damages equal to

back pay which

may be imposed to

penalize willful

violations

116

Punitive damages

available, civil penalties

up to $100,000 are

available in

administrative and

judicial proceedings

117

Punitive damages

available in judicial

proceedings, with no

statutory cap.

118

Civil penalties available

up to $125,000, or

$250,000 for willful

violations, in

administrative

proceedings

119

105

29 U.S.C.A. §§ 621–634.

106

N.Y. EXEC. LAW § 290 et seq. (McKinney 2020).

107

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-101 et seq.

108

29 U.S.C.A. § 631.

109

N.Y. EXEC. LAW § 296(3-a).

110

29 U.S.C.A. § 626(b).

111

See N.Y. EXEC. LAW § 297(4).

112

See N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-120.

113

29 U.S.C.A. § 626(b); Comm’r v. Schleier, 515 U.S. 323, 326 (1995); see

Collazo v. Nicholson, 535 F.3d 41, 45 (1st Cir. 2008).

114

See N.Y. EXEC. LAW § 297(4)(c).

115

See N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-120.

116

29 U.S.C.A. § 626(b).

117

N.Y. EXEC. LAW §§ 297(4)(c)(iv–vii).

118

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-502(a).

119

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-126(a).

19

BURDEN OF

PROOF,

GENERALLY

In cases against

private employers

and state and local

government

employers, age

must be a but-for

cause of the

adverse

employment

action.

120

In cases

against federal

employers,

employment

decisions must be

entirely free from

age discrimination

(although but-for

causation must be

shown to obtain

certain forms of

relief)

121

Must show employer

subjected employee to

“inferior terms,

conditions or privileges

of employment”

because of their age

122

Must show employer

treated employee less

well because of their

age

123

PROVING THAT

DEFENDANT’S

REASON FOR

ADVERSE

EMPLOYMENT

ACTION WAS

PRETEXT FOR

AGE

DISCRIMINATION

To show

employer’s

explanation is

pretext, plaintiff

must show that age

was the “but-for

cause” of the

challenged adverse

employment

action

124

Plaintiff can establish

employer’s proffered

reason was pretext

when it is shown both

that reason was false

and that discrimination

was the real reason

125

Only requires some

evidence that at least

one of the reasons

proffered by the

defendant is false,

misleading, or

incomplete to defeat a

motion to dismiss

126

HOSTILE WORK

ENVIRONMENT

Conduct must be

“severe or

pervasive”

Conduct must subject

plaintiff to “inferior

terms, conditions or

privileges” because of

age.

127

It is an

affirmative defense that

the conduct was

Conduct must treat

plaintiff “less well”

because of age. It is an

affirmative defense that

the behavior was a “petty

slight or trivial

inconvenience”

129

120

See Gross v. FBL Fin. Servs., Inc., 557 U.S. 167, 176 (2009).

121

Babb v. Wilkie, 589 U.S. __ , 140 S. Ct. 1168, 1171 (2020).

122

N.Y. EXEC. LAW § 296(1)(h).

123

Parsons v. JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A., No. 16-CV-0408 (NGG)(JO), 2018 WL 4861379, at *12

(E.D.N.Y. Sept. 30, 2018).

124

Ehrbar v. Forest Hills Hosp., 131 F. Supp. 3d 5 (E.D.N.Y. 2015).

125

Ferrante v. Am. Lung Ass’n, 90 N.Y.2d 623, 630 (1997).

126

Bennett, 92 A.D.3d at 43.

127

N.Y. EXEC. LAW § 296(1)(h).

129

Williams, 61 A.D.3d at 78, 80.

20

nothing more than

“petty slights or trivial

inconveniences”

128

AVAILABILITY

OF DISPARATE

IMPACT THEORY

OF LIABILITY

FOR JOB

APPLICANTS

There is a split

among federal

courts as to

whether or not job

applicants may

benefit from a

disparate impact

theory of

discrimination

(where a neutral

policy

disproportionally

affects older

applicants) under

the ADEA

130

Disparate impact

claims may be brought

by job applicants

131

Disparate impact claims

may be brought by job

applicants

132

EMPLOYER SIZE

Employers with

twenty or more

employees

133

All employers within

the state regardless of

size

134

Employers with four or

more employees and/or

independent

contractors

135

128

Id.

130

See generally Villareal v. R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., 839 F.3d 958 (11th Cir. 2016) (ruling that

job applicants are not able to bring disparate impact claims against employers); see generally Kleber v.

CareFusion Corp., 914 F.3d 480 (7th Cir. 2019) (ruling same), cert. denied, 140 S. Ct. 306, 205 L. Ed. 2d

196 (2019) (ruling same); see generally Rabin v. Pricewaterhouse Coopers LLP, 236 F. Supp. 3d 1126

(N.D. Cal. 2017) (holding job applicants can bring disparate impact claims against employers).

131

See N.Y. EXEC. LAW § 296(1).

132

See N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-107(17).

133

29 U.S.C.A. § 630(b).

134

N.Y. EXEC. LAW § 292(5).

135

N.Y.C. Admin. Code § 8-102. Except for claims of gender-based harassment where there is no

employee minimum. Id.