Primary Care

in the United States

A Chartbook of

Facts and Statistics

Primary Care in the United States 2

Prepared by:

Robert Graham Center (RGC)

1133 Connecticut Avenue NW, Suite 1100

Washington, DC 20036

www.graham-center.org

@TheGrahamCenter

IBM-Watson Health (IBM)

75 Binney St

Cambridge, MA 02142

www.ibm.com/watson-health

The American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) & afliated

Center for Professionalism & Value in Health Care (CPV)

1016 16th Street NW, Suite 700

Washington, DC 20036

https://professionalismandvalue.org/

Contributors:

Brian Antono, RGC

Andrew Bazemore, ABFM/CPV

Irene Dankwa-Mullan, IBM

Judy George, IBM

Anuradha Jetty, RGC

Stephen Petterson, RGC

Amol Rajmane, IBM

Kyu Rhee, IBM

Bedda L. Rosario, IBM

Elisabeth Scheufele, IBM

Joel Willis, ABFM/CPV

Acknowledgements:

Thanks to the many people who contributed to this report

throughout its development at IBM, ABFM, and the Robert

Graham Center. IBM colleagues include: Sean Kennedy, Tim

Bullock, Kay Miller, Amanda Mummert and Sarah Kefayati.

Published February 2021

Suggested Citation:

Willis J, Antono B, Bazemore A, Jetty A, Petterson S, George

J, Rosario BL, Scheufele E, Rajmane A, Dankwa-Mullan I,

Rhee K. The State of Primary Care in the United States:

A Chartbook of Facts and Statistics. October 2020.

Table of

contents

04 Preface

06 Executive Summary

07 I. Introduction

08 Why Primary Care?

09 Ecology of Medical Care

10 II. First Contact

11 Who Provides Primary Care?

11 Primary Care Physicians

12 Primary Care Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants

12 Age Distribution of Primary Care Physicians

13 Primary Care Physicians by Gender

13 Number of Graduates from Primary Care Residencies

14 Where is Primary Care Provided?

14 Ratios of Primary Care Professionals to Population

15 Primary Care Physician to Population Ratios by State

16 Primary Care Physicians by Rural/Urban Geography

16 Primary Care Practices by Ownership

18 III. Continuity

19 Who Visits Primary Care Practices?

19 Ofce Visits to Physicians by Specialty

20 Outpatient Visits to Primary Care Physicians

by Patient Age and Sex

21 IV. Comprehensiveness

22 What Medical Conditions do Primary

Care Physicians Address?

22 Primary Care Physicians’ Scope of Practice

23 Primary Care for Patients with Chronic Conditions

23 Changes in Primary Care Scope of Practice

24 V. Coordination

25 How Does Care Coordination Function in Primary Care?

27 VI. Cost

28 How Much Do We Spend on Primary Care?

29 Expenditures for Primary Care

30 Primary Care Payment Sources

30 Trends in Compensation for Primary Care Providers

31 VII. Preventive Care Visits

32 Why Preventive Care Visits?

33 Trend of Preventive Care Visit Utilization

34 Preventive Care Visit Utilization, Stratied by Age and Sex

35 Preventive Care Visit Utilization, Regional Distribution

36 Preventive Care Visit Utilization, by Health Plan

37 Patients with Preventive Care Visits, Primary Care and Non-

Primary Care Providers

38

Trend of Average Total Cost of Preventive Care Visit Utilization

39 VIII. References

42 Methods Appendix

44 Description of Data Sources

Primary Care in the United States 3

Preface

As we launched this project in the summer of 2019, we

could scarcely have imagined that just 12 months later,

the United States (U.S.) would be beleaguered in a global

pandemic by the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19).

What is even more surprising is that we would submit a

Chartbook for publication in the country facing the world’s

heaviest pandemic burden at that time, despite having the

greatest per capita wealth and health care spending

of any nation. The United States, home to 4% of the world’s

population, currently accounts for about a quarter of

both the world’s COVID-19 cases (4,000,000) and deaths

(150,000).

1,2

Such dismal gures coincide with an overly

specialized, and highly fragmented U.S. health care

system with a long history of underinvestment in both

primary care and public health.

At this moment, the only certainty seems to be more

uncertainty as we nd ourselves coming to grips with a

“new normal.” Yet, as the current situation continues to

evolve, the impact of COVID-19 will be felt far beyond its

population-based effects on morbidity and mortality,

3

with sequelae including:

4

severely strained management

of chronic disease,

5

increase in and worsening of mental

health,

6,7

and associated effects,

8

and exacerbation

9

in

disparity of an already existing and uneven provision

of medical and health care services

10

for vulnerable

populations. Despite the challenges being endured during

this pandemic, the practice of primary care stands to

play a signicant role in the management of these issues,

employing previously underutilized technology such as

telehealth, and overcoming the nancial and physical

limitations imposed by the pandemic on a practice model

built on routinely physician ofce-based patient care.

Primary care is not exempt from the strain facing so many

sectors of the U.S. economy, and health care in particular.

Early convenience sampled surveys administered weekly

to a cohort of over 700 U.S. primary care clinicians (across

49 states) suggested they experienced extreme mental

stress, increased morbidity and mortality among patients

from pandemic-related constraints, resource loss (due to

staff sickness and/or quarantine), and existential nancial

strain.

11

The means by which primary care practices meet

such challenges is evolving, but there is little doubt that

the pandemic will leave an indelible mark on primary care

access, team-structure, size, and delivery.

The health care community has also experienced a

transformation in clinical care delivery. After years of

lamenting the limited use, and sluggish adoption of

telehealth in primary care,

12

the swift pivot and embrace

of this platform by primary care clinicians and patients

alike to accommodate social distancing imperatives has

been remarkable. The demand and use of telehealth

services has accelerated rapidly as new rules relaxed prior

regulations, resulting in exponentially expanding access,

billing, and services.

13

A study by The Commonwealth

Fund showed that as in-person visits dropped early

in the pandemic, telemedicine visits briskly peaked

to 14% of weekly visits through mid-April. By mid-

June, telemedicine visits declined from its peak, but

remained substantially higher than pre-COVID-19 levels.

14

Unfortunately, primary care practices, that were unable to

shift to virtual care, were forced to restrict certain services

or to close.

11

One model examining the nancial impact of COVID-19

on U.S. primary care practices estimates that $15.1 billion

is needed to neutralize revenue losses nationally.

15

Even

assuming a rapid ramp up of telemedicine services to

offset losses of in-person visits, a variety of scenarios

estimates primary care practices losing over $65,000

per full-time equivalent (FTE) physician from current

fee-for-service payment structures.

15

An example in

Virginia demonstrated that a network of 12 primary care

ofces and 500 employees experienced 50% losses in

patient volume and 60% losses in revenue by May 2020

– resulting in furloughs of 50 employees, reduced staff

Primary Care Amidst

a Generational Pandemic

Primary Care in the United States 4

hours, and signicant pay cuts to clinician salaries.

16

Despite such nancial challenges, clinicians and primary

care practices around the country have fought hard to

keep their doors open.

17

As it currently stands, the direct costs of COVID-19

illustrate a disproportionate burden on minority

communities. Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and other

people of color are facing higher rates of hospitalization

or death from COVID-19 compared to non-Hispanic

white persons.

18

People of color have also suffered from

long-standing systemic health and social inequities

leading to higher rates of chronic conditions that worsen

the effects of COVID-19.

19

In addition to direct costs of

COVID-19 are indirect ones, or COVID collateral. These

include but are not limited to missed preventive care

needs, depression, anxiety, substance misuse, and

domestic violence increasingly witnessed by primary care

practices throughout the country.

11

Ultimately, the risks of

signicant morbidity and mortality from these sequelae

may far outweigh the enormous damage by the initial

wave of COVID-19.

With adequate attention and investment, primary care

– in coordination with public and community health

sectors – can mitigate both the long-established health

disparities and indirect sequelae facing the American

public after COVID-19 recedes. Whether this happens

depends on fundamental reforms to infrastructure and

associated payment models, and a renewed prioritization

of core functions. Empowered to provide ‘First Contact’ for

patients suffering directly or indirectly from COVID-19,

and coordinate contact tracing, primary care can help to

reduce emergency room and intensive care unit burden

from unnecessary care, expense, and overwhelmed

capacity. Primary care clinicians can further build on

‘Continuity’ relationships previously established with

their patients to offer reassurance, effective triage, and

certainty in a time rife with more questions than answers.

The ‘Comprehensive’ range of services that primary care

offers across the widest platform of delivery in America can

reduce the collateral damage from COVID-19 to support

patients with chronic diseases whose routine care was

usurped by the urgency of the pandemic and to incorporate

eventual vaccine and possible treatment regimens as they

emerge. And nally, well-supported primary care can

provide our patients and populations with ‘Coordinated’

care, including but not limited to mitigating challenges

in accessing mental health support and services as well

as securing affordable food, medications, and shelter.

Alternatively, the nancial apocalypse ushered in by the

pandemic for many primary care practices could leave

the nation with critical gaps in its most utilized and widely

distributed source of care, exactly when we need it most.

We hope that this Chartbook provides some utility to those

seeking to better understand primary care and to those

working to ensure its viability as we continue through the

pandemic-engendered “new normal.”

Primary Care in the United States 5Preface

Executive

Summary

Primary Care (PC) has entered a new decade facing truly

dynamic times for U.S. politics, culture, health, and the

system charged with its maintenance. And yet, just two

years after the world’s nations reafrmed primary care’s

central role in the achievement of “Health for All,” and as

we await the rst report from the National Academies of

Medicine on High Performing Primary Care since 1996,

20

not much has changed.

Despite renewed interest in strengthening primary

care in the United States in recent years, there remains

an inadequate understanding of what primary care is

and does, insufcient investment in its infrastructure

and growth, inadequacy in its workforce numbers and

distribution, and inefcient coordination with other sectors.

In what follows, we seek to improve upon gaps in knowledge

by offering a snapshot of the facts and gures that make up

contemporary U.S. Primary Care. It is our sincere hope that

such information not only ignites a curiosity to learn more,

but simultaneously serves as a foundation to improve upon

this vital health system function.

The Chartbook is loosely organized around Dr. Barbara

Stareld’s conceptual framing of primary care’s

salutary effects as “4 C’s” - First Contact, Continuity,

Comprehensiveness, and Coordination of care. Through

these four dimensions, Dr. Stareld explained how systems

emphasizing primary care achieved greater access to

higher quality health care at lower costs and with greater

equity across populations.

The analyses conducted within this Chartbook reafrm

Primary Care’s standing as the largest platform of health

care delivery in the United States, an idea rst quantied

and illustrated by the grandfather of Health Services

Research, Dr. Kerr White, in 1961 – and which still holds

true today. Additional analyses also conrm that the

proportion of the U.S. physician workforce in primary care

has diminished to 31% (Table 1), as specialist training

continues to grow in the absence of a National Workforce

Commission or federal agency directing workforce

planning. Hopes that nurse practitioners and physician

assistants might ll the gap remain. However, these groups

face the same incentives to specialize as physicians,

and their proportional PC contributions continue to lag

anticipated levels (Table 2).

Sections II and III of the Chartbook frames basic facts and

gures on patient contact with primary care, by exploring

visits,and how they vary by specialty type, age and gender.

Section IV tackles the frequency and range of conditions

seen in primary care, and how they are changing.

Remarkably, despite representing less than one-third of the

physician workforce, more than 80% of patients

with 8 common chronic conditions saw a primary care

physician for that condition within a two-year period.

Understanding the adequacy of a future PC workforce,

particularly for vulnerable areas and populations, requires

successful denition of who is currently practicing primary

care as well as elucidation of age and gender distributions,

and graduate outputs (Figures 2-4). Recent years have

seen misestimation of primary care physician supply that

have potentially dangerous implications for workforce

planning.

21

For example, Table 1 offers a contemporary

enumeration of the total physician workforce in primary

care. Other gures will help the reader understand the

percentage of the current PC workforce approaching

retirement age, who are serving rural communities, the

distribution across practice ownership types and sizes,

and how the ratios of primary care to population varies

across all 50 states (Figure 5).

In Section V, new analyses inform the coordinating

function of primary care, as exemplied by an evolving

and multifaceted primary care team. New conceptual

approaches to capturing overall investment in primary

care are the subject of Section VI. Using a nationally

representative data source, this section also reveals the

persistent underinvestment in primary care relative

to other sectors.

In Section VII, the Chartbook takes a novel look at

Preventive Care Visit (PCV) utilization. Using the largest

aggregation of commercial data available, we nd that PCV

use has steadily increased over the ten-year period of 2008-

2018. However, the results also suggest that PCV utilization

remains low (28.9% to 44.8% in 2018), particularly among

males and in rural communities and in the Western

U.S., suggesting that there remain policy and practice

opportunities to improve preventive care.

While it would be a daunting task for a chartbook to paint

a complete portrait of a domain as broad as primary care,

we hope that readers will nd the array of facts and gures

collected into this one to be helpful in their understanding

of primary care, well-established as the ‘central’ and

‘essential’ feature of any robust health system.

Primary Care in the United States 6

I. Introduction

Primary Care in the United States 7

Why Primary Care?

In 1978, the nations of the world gathered at Alma-Ata and

declared primary care as the key to attaining “Health for

All.”

25

In 1996, an Institute of Medicine (IOM) report dened

primary care as “the provision of integrated, accessible

health care services by clinicians who are accountable

for addressing a large majority of personal health care

needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients,

and practicing in the context of family and community.”

26

In her seminal work, Dr. Barbara Stareld, preeminent

scholar and health services researcher, conceptualized the

vital role and value of primary care as 4 C’s—First Contact,

Continuity, Comprehensiveness, and Coordination of

care. Over a 25 year career, Stareld reinforced primary

care’s strong association with improvement in overall

health outcomes for persons and populations, including

but not limited to broader access, lower costs, greater

health equity, and higher quality.

27

Presently, in the U.S.

primary care sits on the precipice of a broken health care

system. If strengthened in well-designed, well-delivered,

and well-used ways, the 4 C’s of primary care can provide

a solid foundation for achievement of the quadruple aim—

improving quality of care, health of people and populations,

reducing health care cost, and improving the work life of

health care clinicians and staff.

In 2000, the World Health Organization (WHO) assessed the

world’s health systems and ranked the United States 37

th

out of 191

countries.

22

Despite attempts at improvement, the United States in

2020 continues to woefully underperform in key aspects of health

care services including access, efciency, quality, and equity while

simultaneously spending more on health care than any other system

in the world—over $3 trillion per year.

23

One major culprit is a U.S.

health care system that has become increasingly fragmented in its

delivery, services, and attempts at solutions begetting unsustainability,

ineffectiveness, and more brokenness.

24

U.S. primary care can play

a critical role in reconnecting and correcting a system capable of

achieving safe, high-quality, accessible, equitable, and affordable

health care for all Americans. This chartbook describes the current

state of primary care in the United States presenting information from

a variety of national data sources to answer questions about who, what,

where, and how primary care is being delivered.

1. IntroductionPrimary Care in the United States 8

Figure 1 below shows the proportion of Americans who

seek various types of health care services in an average

month. For every 1,000 people in the United States:

– 800 report symptoms

– 327 consider seeking medical care

– 217 visit a physician’s ofce

(of which 113 visit a primary care physician)

– 104 visit a specialist physician

– 65 visit a complementary

or alternative medical care provider

– 21 visit a hospital-based outpatient clinic

– 14 receive health services at home

– 13 visit an emergency department

– Eight are hospitalized

– Less than one person is hospitalized

in an academic medical center

1. Introduction

Figure 1. The Ecology of Medical Care, 2001

Ecology of Medical Care

Primary care remains the largest platform of health care

delivery in the United States, rst demonstrated by Kerr

White in 1961. Forty years later, an updated and expanded

estimate of the use of all health services calculated the

number of Americans who experience certain health care

events in a typical one-month period. Using multiple data

sources and comparing primary care services to other

medical specialty services, the model showed that more

people seek primary care than any other type of health

care service.

1000 persons

800 report symptoms

327 consider seeking medical care

217 visit a physician’s ofce

(113 visit a primary care physician’s ofce)

65 visit a complimentary or alternative medical

care provider

21 visit a hospital outpatient clinic

14 receive home healthcare

13 visit an emergency department

8 are hospitalized

<1 is hospitalized in an academic medical center

Primary Care in the United States 9

II. First Contact

Primary Care in the United States 10

Who Provides Primary Care?

Unlike many other countries, the U.S. primary care workforce lags

woefully behind its specialty care counterparts. At present, primary

care physicians represent only about one-third of the overall physician

workforce in the United States.

28

This falls far short of the 40 percent

primary care workforce recommended by the Council on Graduate

Medical Education (COGME) report on Advancing Primary Care.

29

Although the 2010 COGME report outlined signicant evidence

demonstrating optimal health outcomes when 40 percent of the

physician workforce are primary care physicians,

the United States

has seen a decades decline in production of primary care physicians

relative to specialty physicians.

30

A closer look reveals declining trends

in U.S. medical graduates choosing family medicine—14 to 8 percent

among allopathic graduates from 2000 to 2005 and 34 to 29 percent

among osteopathic graduates from 2001 to 2008.

29

This decline is

further magnied by the looming retirement of one-quarter of the

primary care physician workforce,

28

and an anticipated increase in

demand for primary care physicians as the U.S. population grows

larger and older. If supply and demand trends persist, the American

Association of Medical Colleges (AAMC) estimates a shortage ranging

between 21,100 and 55,200 primary care physicians by 2032.

31

Primary Care Physicians

In 2019, there were more than 228,000 direct patient

care physicians in the ve major primary care specialties

(Table 1). The major specialty of primary care is family

medicine, accounting for nearly 40 percent of the total

primary care physician workforce, followed by general

internal medicine and general pediatrics. The number of

geriatricians is relatively small. Primary care physicians

make up less than one-third of the physicians who spend

most of their time caring for patients.

28

Table 1. Number of Ofce-Based, Direct Patient Care Physicians by Specialty, 2019

Physician Type Number of Physicians Percent of Primary Care Physicians Percent Total

Total Physicians 730,026 – 100.0%

Non-Primary Care Physicians 501,089 – 68.6%

Total Primary Care Physicians 228,936 100.0% 31.4%

Family Physicians 91,037 39.8% 12.5%

Geriatrics 4,495 2.0% 0.6%

General Practice 5,579 2.4% 0.8%

General Internal Medicine 78,984 34.5% 10.8%

General Pediatrics 48,842 21.3% 6.7%

Source: American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterle, 2019

Primary Care in the United States 112. First Contact

Figure 2. Age Distribution of Primary Care Physicians, 2019

Source: American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterle, 2019

Primary Care Nurse Practitioners

and Physician Assistants

Rapid growth in the number of nurse practitioners (NPs)

and physician assistants (PAs) have offered new hope for

lling gaps in access to primary care. However, the well-

documented decline in physicians choosing primary care

appears to be shared by NPs and PAs, which have seen

similar reductions in primary care as a preferred specialty

choice.

32

In recent reports, debate remains over what

portion of NPs and PAs enter primary care. For example,

the National Commission on Certication of Physician

Assistants (NCCPA) notes that only 25.8% of PAs (25,487)

currently work in primary care settings, versus ndings by

the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality (AHRQ)

in 2016 estimating 43.4% of PAs (36,119) practice primary

care.

33,34

It is clear in either case that ensuring PAs and NPs

entry into and retention in primary care is a challenge,

much like that faced in the physician workforce. Table 2

below shows an updated estimate of the total number

of PAs and NPs, and the proportion of each working in

primary care based on a ‘co-location’ method described

in the Appendix. Lacking the type of data Masterle that

is available to physicians, this is an estimate only.

Table 2. Estimates of Nurse Practitioners and Physician Assistants in Primary Care, 2020

Provider Type Total Number Percent in Primary Care Number in Primary Care

Nurse Practitioners 220,332 42.8% 94,302

Physician Assistants 118,195 35.7% 42,195

Source: Medicare Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System (PECOS), 2020

<35 35-39

0

5K

10K

15K

20K

25K

30K

35K

40K

40-44 45-49 50-54 55-59 60-64 65-69 70-74 75-80 80-84 85+

Age Distribution of Primary Care Physicians

Most primary care physicians arrive in the workforce in

their late 20s, and typically remain in the workforce for 40

years. The increased interest in primary care in the late

1990s likely explains the age peak of physicians in the mid-

late 40s (Figure 2). In 2019, nearly one-quarter of primary

care physicians were aged 60 years and older.

28

Compared to physicians, physician assistants (PAs) in

primary care tend to be younger on average. Only 14% of

primary care PAs are aged 60 years or older. The median

age is 40 years.

35

Age distribution data were not available for

primary care nurse practitioners.

Primary Care in the United States 122. First Contact

Figure 3. Primary Care Physicians by Gender and Specialty, 2019

Source: American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterle, 2019

Primary Care Physicians by Gender

The primary care physician (PCP) workforce in many

industrialized nations is increasingly female. In recent

decades, the proportion of PCPs who are women has

doubled or nearly doubled, often outpacing non-primary

care specialties in these industrialized countries.

36,37

Family Practice

Female Male

Geriatrics

General Practice

Internal Medicine

Pediatrics

All Primary Care Physicians

65%53%

46%

39%

26%

35%

47%

54%

61%

74%

Number of Graduates from Primary Care Residencies

The number of graduates from primary care residency

training programs peaked in the late 1990s and

subsequently declined for the next decade (Figure 4).

There appears to be a growth in the number of graduates

in recent years, though there is a long lag period after

Figure 4. Primary Care Physicians by Year of Residency Graduation, 1980-2015

Source: American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterle, 2019

5K

1980-1989 1990-1999 2000-2009 2010-2015

6K

7K

8K

9K

10K

42% 58%

There is an increasing balance by gender across most

of the primary care disciplines, and as of 2019, a majority

of pediatricians, geriatricians, and nurse practitioners

are women (Figure 3).

completion of training before a physician’s practice

specialty or location is certain. Data sources, such

as the AMA Physician Masterle, reect this period

of uncertainty for recent residency graduates.

Primary Care in the United States 132. First Contact

Where is Primary Care Provided?

Over a hundred years ago, Abraham Flexner noted the

disproportionate geographic distribution of physicians

38

–

an enduring access problem re-emphasized in numerous

federal agency reports and expert panels in recent decades.

According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation

and Development (OECD), the number of physicians per

1,000 residents in the United States is slightly lower than

the average in other similarly developed OECD countries —

2.6 for the United States compared to the OECD average of

3.5.

39

However, signicant state-level variation exists within

the United States.

40

Compared to any other specialty group, family physicians,

primary care nurse practitioners, and primary care

physician assistants are more likely to provide care in rural

and remote areas. The number of providers at practice

sites also varies signicantly, but as recently as 2016, the

majority of clinic sites have ve or fewer providers.

41

Ratios of Primary Care Professionals to Population

There are 223.1 physicians per 100,000 persons in the

United States. Of those, nearly one-third (70/223.1) are

primary care physicians (Table 3). There are 111.7 primary

care providers overall per 100,000 population, including

physicians, physician assistants, and nurse practitioners.

This translates to one primary care physician for about

every 1,429 people in the United States, and one primary

care professional for every 895 people.

28,42,43

There are substantial variations across the primary

care specialties and professions. Pediatric and geriatric

physician ratios are adjusted for the appropriate

population ages. Physician assistant and nurse

practitioner ratios are considerably higher because of

the smaller number of professionals. Table 3 shows both

the number of health care professionals per 100,000

population and the ratio of persons per provider.

28,42,43

Table 3. Primary Care Professionals

per 100,000 Population by Specialty, 2019

Specialty Providers

per 100,000

Persons

per Provider

Family Medicine 27.8 3,594

General Practice 1.7 58,643

General Internal Medicine 24.1 4,142

Geriatrics* 8.6 11,664

General Pediatrics

+

66.5 1,503

Primary Care Nurse

Practitioners

28.8 3,470

Primary Care Physician

Assistants

12.9 7,754

All Primary Care Physicians 70.0 1,429

All Primary Care Providers 111.7 895

All Physicians 223.1 448

Sources:

American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterle, 2019 (Physicians)

Medicare Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System (PECOS),

2020 (NP/PA)

United States Census Bureau, 2018 population estimates

*Population: Persons over age 65

+Population: Persons under age 18

Primary Care in the United States 142. First Contact

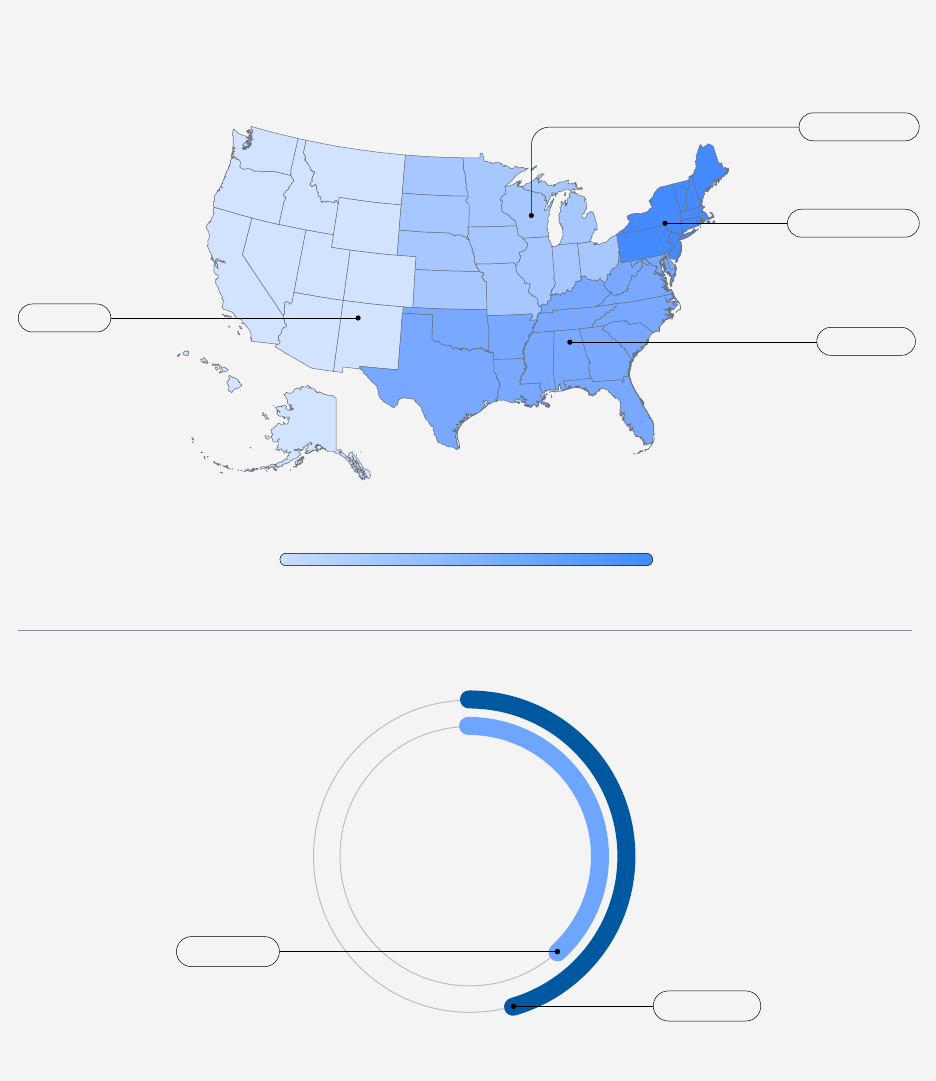

Primary Care Physician to Population Ratios by State

The number of primary care physicians per 100,000

population varies signicantly by state (Figure 5).

Mississippi has the lowest, with 49.1, and Vermont the

highest, with 103.9 primary care physicians per 100,000

people. The District of Columbia has an even higher

physician-to-population ratio of 130.7. The Northeast,

Northwest, and northern Midwest regions have the highest

ratios of primary care physicians per population.

28

Source: American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterle, 2019;

United States Census Bureau, 2019 population estimates

44

MS

NV

UT

TX

OK

KY

AL

ID

AZ

GA

SC

IN

LA

AR

TN

MO

NC

FL

WY

IA

NM

OH

NE

DE

VA

KS

49.1

52.6

52.7

55.5

56.1

58.3

58,6

58.9

60.0

60.1

60.6

60.6

61.7

62.7

63.2

64.4

64.5

66.0

66.3

67.4

68.9

69.0

69.1

69.2

69.5

69.6

69.7

70.8

71.1

72.1

72.4

72.5

73.0

73.4

74.1

74.9

75.1

75.2

75.4

77.0

79.3

80.8

82.4

84.5

85.2

88.7

89.0

91.0

91.3

100.3

103.9

130.7

ND

MI

SD

IL

CA

WI

PA

WV

CT

MT

CO

NJ

NY

WA

MD

MN

NH

OR

HI

RI

PR

MA

AK

ME

VT

DC

Figure 5. Primary Care Physicians per 100,000 Population by State, 2019

Primary Care in the United States 152. First Contact

Figure 6. Primary Care Physicians by Employment Status

Source: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), 2016

Primary Care Physicians by Rural/Urban Geography

Table 4 shows that primary care physicians are better

represented in rural areas than specialist physicians.

Among primary care physicians, family physicians and

general practice physicians are more highly concentrated

Owner, physician practice

Owner, insurance company or health plan, HMO, or other

Employee, physician owned practice

Employee, not physician owned practice

Contractor

4%

1%

48%

16%

32%

in rural areas compared to geriatricians, internists, and

pediatricians. Conversely, geriatricians, internists, and

pediatricians are as highly concentrated in urban areas as

specialist physicians.

Table 4. Primary Care Physicians by Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) Designation

Rural

Status

Percent

of U.S.

Population

Non-Primary

Care

Primary

Care

Family

Medicine

Geriatrics General

Practice

Internal

Medicine

Pediatrics

Urban 84.2% 95.1% 91.8% 87.6% 95.9% 87.6% 94.7% 95.1%

Large Rural 8.7% 3.3% 4.5% 6.2% 2.3% 5.8% 3.3% 3.2%

Small Rural 4.1% 0.9% 2.2% 3.8% 0.9% 3.6% 1.1% 1.0%

Isolated Rural 3.0% 0.4% 1.1% 2.1% 0.6% 2.3% 0.5% 0.4%

Sources: American Medical Association (AMA) Physician Masterle, 2019

American Community Survey (ACS), 5-Year Summary File, 2014-2018 population estimates

45

Rural-Urban Commuting Area (RUCA) Codes

46

Primary Care Practices by Ownership

Some primary care physicians own their practices,

while others work as employees of another physician,

as employees in non-physician owned practices, or as

independent contractors (Figure 6). The majority of

primary care ofces are owned by a physician or physician

group. Nearly half (48%) of primary care physicians are

full or partial owners of their practices, which is a decline

compared to our previous calculation.

47

Conversely, the

other half (48%) of primary care physicians belong to a

rapidly growing cohort of employed physicians. Of the

48% employed primary care physicians, two-thirds work

in non-physician owned practices while one-third work in

physician owned practices. A small percentage of primary

care physicians (4%) are independent contractors.

Primary Care in the United States 162. First Contact

Figure 7. Distribution of Primary Care Physicians

in Non-Physician Owned Practices

Source: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), 2016

Of the primary care physicians who work in non-physician

owned practices, half (50%) are in practices owned

by insurers, health plans, HMOs, or other corporate

entities. Approximately 47% are in medical, academic, or

community health centers (Figure 7).

Medical/academic health center;

Community health center; other hospital

Insurance company, health plan, or HMO;

other health corporation; other

Other

3%

47%

50%

Primary Care in the United States 172. First Contact

III. Continuity

Primary Care in the United States 18

Who Visits Primary Care Practices?

In 2016, Americans made nearly 900 million visits to ofce-based

physicians with almost half of those visits made to primary care

physicians.

48

As previously discussed, many Americans also seek

primary care services from nurse practitioners and physician

assistants, though their scope of practice varies by state and by practice

site. The benets to populations that establish a relationship with

primary care are numerous in the literature. Consistently, studies show

a link between having a primary care provider and improved patient

health outcomes with a simultaneous reduction in overall cost for health

care services and utilization.

49,50

Ofce Visits to Physicians by Specialty

The largest number of ofce-based primary care physician

visits (over 200 million) were to family medicine or general

practice physicians (Table 5). Visits to general pediatricians

and general internists represent the second and third-most

visited primary care specialties, with more than 207 million

combined visits.

Table 5. Physician Ofce Visits by Specialty

Physician Specialty Number of Visits Percent of Visits

General and

Family Medicine

202,494,171 22.9%

Internal Medicine 81,700,886 9.2%

Pediatrics 126,063,214 14.3%

All Primary Care 410,258,271 46.4%

Other Medical

Specialties

238,945,991 27.0%

Surgical Specialties 234,520,916 26.5%

All Visits 883,725,178 100.0%

Primary Care in the United States 193. Continuity

Figure 8 shows the proportion of ofce visits to primary

care physicians and specialists compared to each

specialty’s percentage of total workforce.

Figure 8. Visits to Ofce-Based Physicians by Specialty

Outpatient Visits to Primary Care Physicians by Patient Age and Sex

The number of visits to primary care physicians varies

by age and sex (Figure 9). According to the Medical

Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS),

51

which provides

nationally representative information about all health

services in the United States, the youngest (< 1 year) and

oldest patients (75+ years) tend to visit primary care

0%

0

1

2

3

4

General and

Family Medicine

Internal Medicine Pediatrics All Primary Care All Other

Specialties

10%

20%

30%

50%

40%

60%

0 1-4 5-9 10-14 15-17 18-24 25-29 20-54 55-64 65-74 75+

Female

Male

Percent of Visits

Percent of Workforce

Source: National Ambulatory

Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), 2016

Figure 9. Primary Care Ofce Visits by Age and Sex, 2017

Source: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), 2017

offices most frequently. The youngest age group averages

nearly 4 visits per year; older age groups average 2.5 to

3 visits per year. Across all age groups, females have a

higher mean number of primary care office visits (1.47)

per year than males (1.24).

Primary Care in the United States 203. Continuity

IV. Comprehensiveness

Primary Care in the United States 21

Primary Care Physicians’ Scope of Practice

Primary care physicians continue to care for the broadest

range of conditions and illnesses among the physician

specialties. One lens on the scope of physician practice

is the distribution of the diagnosis codes in their billing

for services rendered. The number of diagnosis codes

used by primary care physicians is broader than that of

non-primary care physicians, whose diagnosis codes

What Medical Conditions do Primary Care Physicians Address?

Primary care physicians care for patients of all ages and with a broad

range of acute and chronic physical and psychological conditions,

including multiple chronic conditions. Primary care physicians also

deliver clinical preventive services, provide patient education, and

perform procedures from minor (e.g. skin biopsy) to major (labor and

delivery). Comprehensive care delivers better clinical outcomes for

patients and lowers overall health spending for the health system.

52

Figure 10. Scope of Practice by Number of ICD-10 Diagnosis Codes

for Primary Care and Selected Physician Specialties

Source: National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), 2016

General/family practice

Internal medicine

Pediatrics

Otolaryngology

Obstetrics and gynecology

Dermatology

Orthopedic surgery

Neurology

General surgery

Ophthalmology

Urology

Cardiovascular diseases

Psychiatry

200 400 600 800 1,0000

cluster around the organs or illnesses of their specialty.

Figure 10 indicates the number of unique International

Classication of Disease, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis

codes by primary care and selected specialties. Primary

care physicians treat a wide range of conditions along the

spectrum of ICD-classied conditions.

Primary Care in the United States 224. Comprehensiveness

Primary Care for Patients with Chronic Conditions

Chronic conditions are prolonged in duration. They

include hypertension, arthritis, diabetes, heart disease,

and asthma. Today, six of every ten adults in the United

States have at least one chronic condition.

53

Primary care

physicians care for a large portion of patients with chronic

diseases. Primary care nurse practitioners and physician

assistants see patients with these chronic diseases as

well. However, data about the care they provide are not

easily accessible. Within a group of eight common chronic

diseases, primary care physicians see a large proportion of

patients with these conditions (Table 6). For example, 61

million Americans with high blood pressure sought care in

2017 and 81% of them visited a primary care physician.

More people with hypertension, diabetes, and asthma visit

a primary care physician each year than visit a specialist

for treatment of these conditions. Even people with less

common, severe chronic diseases, such as Parkinson’s

disease, generally see a primary care physician each year,

in addition to seeing a specialist, such as a neurologist.

Changes in Primary Care Scope of Practice

Scope of practice is changing across the primary care

disciplines, none so dramatically perhaps as in family

medicine. As the gures above and below reects, family

physicians are increasingly likely to care for complex,

multimorbid patients in the outpatient and community

setting, and less likely to report care in a hospital setting

they once commonly tread. Similar trends have been

observed in other settings of care for family physicians

– e.g. prenatal care, home visits, nursing home care, and

obstetric care.

54

Not all of these trends reect trainee intent,

and early studies linking broader scope to positive policy

outcomes and lower burnout suggest the need for further

research on the impact that shifting scope may have on

patients and health systems.

55

Condition Total

Patients

Saw Primary

Care Physician

Saw Subspecialist

Hypertension 61,329,148 49,859,952 81% 44,001,040 72%

Arthritis 27,601,748 22,029,728 80% 22,303,648 81%

Diabetes 24,984,656 20,862,664 84% 18,365,792 74%

Asthma 19,485,934 15,721,782 81% 12,798,045 66%

Glaucoma 4,838,642 3,880,411 80% 4,555,869 94%

Macular Degeneration 2,724,906 2,212,159 81% 2,603,656 96%

Congestive Heart Failure 1,797,097 1,440,255 80% 1,545,735 86%

Parkinson's 598,042 514,940 86% 506,450 85%

Source: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), 2017

Table 6. Patients with Chronic Conditions Who Visited or Talked to a Physician, 2017

Table 7. Family Physicians’ Self-Reported Provision of Inpatient Care, 2013-2018

Year of Survey 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017* 2018*

Total FPs surveyed 10,673 10,064 8,464 8,886 8,675 8,727

FPs reporting inpatient care 3,637 3,386 2,551 2,551 2,182 2,091

Share of FPs reporting inpatient care 34.1% 33.6% 30.9% 28.7% 25.2% 23.9%

Source: American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) Demographic Survey, 2013-2018.

FP: family physician. Sample restricted to FPs in direct patient care

*In 2017 and 2018, ABFM Diplomates were asked whether they provided “adult inpatient care” instead of “inpatient care” in the previous years.

Primary Care in the United States 234. Comprehensiveness

V. Coordination

Primary Care in the United States 24

Figure 11. Percentage of Family Physicians Reporting Having a Care Coordinator at Their Primary Practice,

by Practice Size and Patient-Centered Medical Home (PCMH) Status

How Does Care Coordination Function in Primary Care

According to the Institute of Medicine, “primary care is the provision

of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are

accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care

needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing

in the context of family and community.”

56

A model encompassing this

type of care is known as the Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH),

originally introduced by the American Academy of Pediatrics in 1967

and re-energized through accreditation programs in 2008. PCMH

has since focused on activities of care coordination, enhanced access

and payment reform.

57

Several primary care practices in the United

States have adopted the PCMH model and in so doing have been able to

increase their coordination capabilities (Figure 11).

58

Source: American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) Recertication Examination Application Survey, 2016

0%

10%

20%

30%

70%

50%

90%

40%

80%

60%

100%

Solo Small

(2-5 Providers)

Medium

(6-20 Providers)

Large

(>20 Providers)

PCMH = Yes (N=716)

PCMH = No (N=1,241)

Primary Care in the United States 255. Coordination

Table 8. Percent Family Physicians Working Alongside Other Health Care Providers by Year

Provider 2014

(N=10,836)

2015

(N=9,198)

2016

(N=9,780)

2017

(N=8,161)

2018

(N=8,026)

Nurse Practitioner* 54.0 55.9 59.9 53.7 55.9

Registered Nurse* 47.0 48.7 49.8 53.5 53.8

Physician Assistant* 41.3 42.8 44.3 41.6 42.5

Licensed Practical Nurse* 34.5 35.1 37.1 49.7 49.3

Clinical pharmacist* 21.7 22.9 24.8 24.9 25.8

Behavior Specialist* 21.2 22.7 24.2 24.5 26.3

Social Worker* 20.9 22.0 24.6 24.0 26.3

PT/OT 14.8 16.4 17.5 14.5 14.4

Psychiatrist 12.1 12.5 14.2 13.1 13.1

Midwife 4.6 4.0 4.3 4.6 5.0

Reproduced by permission of the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM)

Source: 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, and 2018 ABFM Recertication Examination Application Surveys.

PT, physical therapist; OT, occupational therapist.

* Signicant to the P < .001.

Primary care, more than any other specialty, is uniquely

suited to coordinate care in a way that meets the needs of

the people it serves. Indeed, there are various health care

providers whose roles in primary care clinics improve the

overall health and welfare of patients through meeting

multifaceted needs, including but not limited to the realm

of social work, behavioral health, physical therapy, and

clinical pharmacy. Furthermore, collaboration between

family physicians and other health care providers appears

to be on the rise (Table 8).

59

Primary Care in the United States 265. Coordination

VI. Cost

Primary Care in the United States 27

How Much Do We Spend on Primary Care?

According to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS),

total health care spending in the United States reached $3.6 trillion

in 2018.

60

Despite being the largest specialty in the U.S. health system,

primary care accounts for a mere 5-7% of total health care spending.

61

This investment pales in comparison to other developed nations who

average 14% of their total health care spending on primary care.

62

As the

United States evaluates its primary care investment, the Primary Care

Spend model (Figure 12) may be a useful tool – a framework appraising

primary care resource allocation and prioritization in the context of a

system’s overall health budget, while simultaneously acknowledging the

complex multifaceted components of primary care.

63

Figure 12. The Constituent Components of the Primary Care Spend Model

Reprinted with permission. © (2019). BMJ. All rights reserved. Adapted by permission from BMJ Publishing Group Limited. [publication title, author, volume number,

pagenumbers, copyright notice year]

Spending on primary care provided

within the context of the 4Cs (rst

contact, continuous, comprehensive,

& coordinated care)

Spending on the provision

of primary care services delivered

by primary care professionals

Spending on essential

primare care services

Total primary care spend

Total Healthcare spending

Primary Care in the United States 286. Cost

Expenditures for Primary Care

According to the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey

(MEPS), which captures household expense data for non-

institutionalized populations in the United States, ofce-

based primary care accounted for only ve percent of

total health expenditures in 2017 (Table 9). Furthermore,

Americans spent three times more on ofce-based

specialist services than primary care services.

Table 9. Expenditures on Health Care by Service Type

Services Total Expenses (In Millions) Percent of Total

Primary care, ofce-based $91,663 5.3%

Specialist, ofce-based $273,565 15.9%

Non-physician, ofce-based $211,999 12.3%

Emergency room $64,153 3.7%

Prescriptions $409,409 23.8%

Home Health $96,959 5.6%

Dental $106,156 6.2%

Inpatient $422,364 24.5%

Vision $17,943 1.0%

Other $28,918 1.7%

Total $1,723,130 100.0%

Source: Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS), 2017.

Note: Ofce-based and outpatient expenditures consist of facility and physician expenses for all ofce-based and outpatient visits.

‘Other’ includes expenditures on medical equipment and services.

Primary Care in the United States 296. Cost

Trends in Compensation for Primary Care Providers

While physician compensation has steadily increased in

recent years, primary care physicians continue to earn

much less than their specialist counterparts.

65

The 2020

Provider Compensation and Production Report from the

Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) revealed

that primary care physicians earned a median total

compensation of $273,437 in 2019, compared to $448,353

for specialist physicians.

66

Notably, however, was the rise

in median primary care physician compensation (10.46%)

outpacing that of specialist physicians (7.78%) between

2014 and 2018.

67

Perhaps more striking was a 12% rise in

family medicine physician median compensation, despite

little change to ‘work relative value units’ (wRVU) – a

measure of clinical productivity – over the same period.

This incongruent relationship between productivity and

compensation exposes the potential for two broader trends:

(1) a growing recognition of the primary care workforce

shortage that has made primary care physicians a valuable

commodity in a competitive market, and (2) the rise in

value-based incentives that has shifted the calculus for

physician compensation from volume (fee-for service) to

quality that primary care provides.

68

Additional factors that

inuence compensation include specialty, practice setting

(academic vs. private practice), and geographic location.

more than half of their patients have commercial insurance.

Internists care for a large number of elderly patients,

which is reected in the high percentage of patients who

participate in Medicare. General pediatricians see a larger

percentage of children, which is reected in the high

percentage of patients who participate in Medicaid.

64

Figure 13. Primary Care Payment Sources, 2014

Source: Medical Group Management Association (MGMA), Cost and Revenue Survey, 2015

Primary Care Payment Sources

The proportion of care provided for patients using public

health insurance (Medicare and Medicaid) varies among

the three major primary care specialties: family medicine,

internal medicine, and pediatrics (Figure 13). This is largely

reective of the age ranges of the patients that different

primary care specialists treat. For all three specialties,

0%

10%

20%

30%

70%

50%

40%

60%

Family Medicine

Internal Medicine

Pediatrics

Medicare Medicaid Commercial Self-Pay Other

Primary Care in the United States 306. Cost

VII. Preventive Care Visits

Primary Care in the United States 31

Why Preventive Care Visits?

A cornerstone of primary care practice is the delivery of preventive

care where the consistent delivery of preventive care services

contributes to the fundamental medical practice components of the

quadruple aim. In particular, major contributions include improving

the health of people and population, and reducing health care cost.

69,70,71

To promote utilization, the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) enacted

into law the provision for preventive care services to be covered by

insurances at no cost to patients.

72

However, recently, the U.S. has failed

to reach the 4 goals for clinical preventive care set out by Health People

2020 (which, for 2019, included colorectal screening, blood pressure

and blood glucose control, and childhood immunizations).

73

Even in

commercially insured individuals, which is 55% of the U.S. population

74

and the largest source of revenue for primary care practices,

75

recommended preventive care is not received by all.

76,77

The relationship that a patient has with their primary care provider

and primary care organization has a great impact on mitigating their

individual health risks and is associated with greater adherence to

preventive care services.

78,79

These services are typically addressed

with patients during physician ofce encounters, and for both

children, and adults, these visits are expected to be billed as preventive

medicine encounters according to CPT

®

terminology.

80,81

This report

denes the set of preventive medicine encounters as Preventive

Care Visits (PCV) and describes the utilization of PCVs using the IBM

®

MarketScan

®

Commercial Research Database, which is a large sample

of a commercially insured population and their dependents in the

U.S.

82

This report focuses primarily on PCV utilization, which is dened

as the proportion of individuals who had at least one PCV within a given

year, as well as the trend of utilization from 2008 to 2018. In particular,

for the year of 2018, PCV utilization is stratied by individual patient

factors that may inuence the consumption of or access to medical

care and include age, sex, U.S. region of residence, and insurance

plan type.

83,84,85

Primary Care in the United States 327. Preventive Care Visits

Figure 14. Trend of Preventive Care Visit Utilization, 2008–2018

Source: IBM Marketscan, 2008-2018

Trend of Preventive Care Visit Utilization

From 2008 to 2018, the number of outpatient encounters

billed as preventive care visits steadily increased from 30%

in 2008 to 44% in 2018, through the transition stages of the

ACA legislation.

2008

50%

45%

40%

35%

30%

25%

20%

Preventive Care Visit Utilization

Year

2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

Primary Care in the United States 337. Preventive Care Visits

Preventive Care Visit Utilization,

Stratied by Age and Sex

In 2018, females have a higher proportion of preventive

care visits when compared against males, by 53% vs

36%, respectively. From age 15 to 64 years, women have

consistently higher PCV utilization when compared against

men. In particular, the preventive care visit utilization for

females aged 18-24 (41%), 25-39 (47%), 40-54 (53%) and

55-64 (52%) years were higher than for males in those age

groups (18%, 21%, 30%, 37%, respectively). With regard to

age, PCV utilization were higher with children than adults.

Proportions were particularly high (above 80%), in the rst

year of life and in years 1-4.

The proportion for children with age ranges 5-9 years and

10-14 years were around 60% across the board for males

and females. The lowest PCV utilization was in males and

females at ages 18-24, with results for females still over

twice as high as males, 41% vs 18%, respectively. The PCV

utilization begins to uptick after the age group of 18-24

years, reaching the highest post-adolescent rates of 53% for

females at 40-54 years and 37% for males at 55-64 years.

Table 10. Preventive Care Visit Utilization, Stratied by Age and Sex

Age Group (in years) Overall Female Male

0 86.34% 86.38% 86.29%

1-4 84.06% 83.81% 84.31%

5-9 63.43% 62.98% 63.86%

10-14 60.49% 60.39% 60.59%

15-17 51.30% 53.13% 49.58%

18-24 28.88% 41.16% 17.51%

25-39 34.01% 47.14% 20.80%

40-54 41.54% 52.72% 29.93%

55-64 44.84% 51.74% 37.47%

Source: IBM Marketscan, 2018

Figure 15. Preventive Care Visit Utilization, Stratied by Age and Sex, 2018

Source: IBM Marketscan, 2018

0 1-4 5-9 10-14 15-17 18-24 25-39 40-54 55-64

Female

Male

Preventive Care Visit Utilization

Age Group ( Years)

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Primary Care in the United States 347. Preventive Care Visits

Preventive Care Visit Utilization, Regional Distribution

In 2018, the PCV utilization by U.S. geographical regions

were 43% for the South, 38% for the West, 45% for the

Midwest, and 53% for the Northeast. Also, the rates were

higher for urban (45%) regions than for rural (35%) regions.

West: 38%

U.S. Census Geographical Regions

Rural vs Urban, U.S.

38% 53%

Midwest: 45%

South: 43%

Urban: 45%

Rural: 35%

Northeast: 53%

Preventive care

visit ultilization (%)

Source: IBM Marketscan, 2018

Figure 16. Preventive Care Visit Utilization, by U.S. Region, 2018

Primary Care in the United States 357. Preventive Care Visits

Source: IBM Marketscan, 2018

Preventive Care Visit Utilization, by Health Plan

The health plans types that are billing for PCVs within

this database include point of service (POS) plan with

capitation, high deductible plans, consumer-driven health

plan (CDHP), POS, exclusive provider organization (EPO),

preferred provider organization (PPO), health maintenance

organization (HMO), and fee-for-service (FFS).

POS with

capitation

High

deductible

CDHP POS EPO PPO HMO FFS

Preventive Care Visit Utilization

Health Plan

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

In 2018, preventive care visit utilization by health

insurance plan ranged from 40% to 48%. PCV rates were

higher for the POS with capitation plan (48%) and lowest

for the fee for service plan (40%) when compared to other

health plans.

Figure 17. Preventive Care Visit Utilization, by Health Plan, 2018

Primary Care in the United States 367. Preventive Care Visits

Patients with Preventive Care Visits, Primary Care

and Non-Primary Care Providers

Primary care providers billing for PCV encounters

encompass physicians in family practice, internal

medicine, pediatrics, and obstetrics and gynecology, as

well as nurse practitioners (NP) and physician assistants

(PA) in primary care. Non-primary care providers were

also included (e.g., endocrinologist, cardiologist) if they

billed for preventive care visits. We included geriatricians

to be complete, but as our cohort does not include patients

65 years and older, there were not many PCVs billed

by geriatricians (about 0.05%) in this report. Provider

types/specialties were derived from the claims-based

classications of the provider who billed the service.

A total of 71,558,728 patients had preventive care visits

in 2018. Family practice and pediatricians saw the largest

number of patients for preventive care visits, accounting

for 27% and 26% of the total number of all patients who

had preventive care visits, respectively. With regard to

non-physician providers, NP had 3% and PA had 1% of all

patients who had preventive care visits. Family practice,

internal medicine, pediatrician, geriatric medicine,

nurse practitioner, physician assistant, obstetrics and

gynecology accounted for approximately 95% of all

patients who had preventive care visits. Non-preventive

care provider or other type of practitioner accounted for

14% of the total number of patients who had preventive

care visits. (Provider type % sum can be greater than

100% because beneciaries can have more than one

preventive care visit per year.)

Figure 18. Distribution of Patients with Preventative Care Visits Across Provider Types, 2018

Source: IBM Marketscan, 2018

Family Practice Pediatrics Obstetric &

Gynecology

Internal Medicine Non-Primary

Care Provider

Nurse Practicioner/

Physician Assistant

Proportions of Patients with

Preventative Care Visits

Provider Type

0%

5%

10%

15%

20%

25%

30%

Primary Care in the United States 377. Preventive Care Visits

Trend of Average Total Cost

of Preventive Care Visit Utilization

The PCV costs reect the total payments made by the health

plan and the patient, including out-of-pocket costs, after

any contractual discounts. The average total cost for PCVs

per member per year (PMPY) for 2018 was $182. When

compared to the average total cost for PCV PMPY in 2008

of $160, there was an increase of 14% over the timespan.

Figure 19. Trend of Average Total Cost of Preventive Care Visits, 2008–2018

Source: IBM Marketscan, 2018

The average annual PCV cost increase is approximately

1% over those 10 years and after adjusting for the 2018

consumer price index for medical care. By U.S. Census

region, the average total costs of PCV PMPY for 2018 are

$181 for the Midwest, $198 for the Northeast, $162 for

the South and $202 for the West.

Year

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

$145

$150

$155

$160

$165

$170

$175

$180

$185

Average Total Preventive Care Visit Cost

(per member per year)

Primary Care in the United States 387. Preventive Care Visits

VIII. References

1. World Health Organization. Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Situation Report - 174. 2020.

https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200712-covid-

19-sitrep-174.pdf?sfvrsn=5d1c1b2c_2. Accessed July 13, 2020.

2. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019: Cases in the U.S.

Published Aug 3, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-

in-us.html. Accessed Aug 4, 2020.

3. Excess Deaths Associated with COVID-19. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/

excess_deaths.html. Accessed August 5, 2020

4. The need to atten the 4 curves of COVID-19. https://www.ibm.com/blogs/watson-health/

atten-the-curves-of-covid-19/ Accessed August 5, 2020

5. Rubin R. COVID-19’s Crushing Effects on Medical Practices, Some of Which Might Not

Survive. JAMA. 2020;324(4):321–323. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.11254

6. Torales J, O’Higgins M, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Ventriglio A. The outbreak of COVID-19

coronavirus and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66(4):317-

320. doi:10.1177/0020764020915212

7. COVID-19 is affecting Black, Indigenous, Latinx, and other people of color the most. https://

covidtracking.com/race. Accessed August 5, 2020

8. Provisional Drug Overdose Death Counts. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-

overdose-data.htm. Accessed August 5, 2020

9. Provisional Death Counts for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) https://www.cdc.gov/

nchs/nvss/vsrr/covid19/health_disparities.htm. Accessed August 5, 2020

10. Kanter GP, Segal AG, Groeneveld PW. Income Disparities In Access To Critical Care Services.

Health Aff (Millwood). 2020;39(8):1362-1367. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00581

11. Primary Care Collaborative. Quick COVID-19 Primary Care Survey: Series 15, Fielded June

26-29, 2020. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d7ff8184cf0e01e4566cb02/t/5efcd6

35282fcf7d1f1282ff/1593628214171/C19+Series+15+National+Executive+Summary.pdf.

Accessed July 9, 2020.

12. Moore MA, Coffman M, Jetty A, Klink K, Petterson S, Bazemore A. Family Physicians Report

Considerable Interest in, but Limited Use of, Telehealth Services. J Am Board Fam Med.

2017;30(3):320-330. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2017.03.160201.

13. Center for Connected Health Policy. Telehealth Coverage Policies in the Time of COVID-19.

Published April 30, 2020. https://www.cchpca.org/resources/covid-19-telehealth-coverage-

policies. Accessed July 13, 2020.

14. Mehrotra A, Chernew M, Linetsky D, Hatch H, Cutler D. The Impact of the COVID-19

Pandemic on Outpatient Visits: A Rebound Emerges. To the Point (blog), Commonwealth

Fund. Published May 19, 2020. https://doi.org/10.26099/ds9e-jm36. Accessed July 13, 2020.

15. Basu S, Phillips RS, Phillips R, Peterson LE, Landon BE. Primary Care Practice Finances In

The United States Amid The COVID-19 Pandemic. Health Affairs. Published online June 25,

2020:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00794. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00794.

16. Kimball S. Doctors face pay cuts, furloughs and supply shortages as coronavirus

pushes primary care to the brink. CNBC. Published May 25, 2020. https://www.cnbc.

com/2020/05/25/coronavirus-family-doctors-face-pay-cuts-furloughs-and-supply-

shortages.html. Accessed July 16, 2020.

17. Phillips RL, Bazemore A, Baum A. The COVID-19 Tsunami: The Tide Goes Out Before It

Comes In. Health Affairs Blog. Published April 17, 2020. 10.1377/hblog20200415.293535.

Accessed July 8, 2020.

18. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus Disease 2019: Racial and Ethnic

Minority Groups. Published February 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-

ncov/need-extra-precautions/racial-ethnic-minorities.html. Accessed July 16, 2020.

19. Nania R. Blacks, Hispanics Hit Harder by the Coronavirus, Early U.S. Data Show. AARP.

Published May 8, 2020. http://www.aarp.org/health/conditions-treatments/info-2020/

minority-communities-covid-19.html. Accessed July 16, 2020.

20. National Academy of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Implementing High-Quality

Primary Care. https://www.nationalacademies.org/our-work/implementing-high-quality-

primary-care. Accessed July 27, 2020.

21. Bazemore A, Petterson S, Levin Z. Comparing Spending on Medical Care in the United States

and Other Countries. JAMA. 2018;320(8):839-839. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.8004

22. World Health Organization. The World Health Report 2000: Health Systems: Improving

Performance. Geneva, Switzerland; 2000. https://www.who.int/whr/2000/en/whr00_

en.pdf?ua=1. Accessed July 8, 2020.

23. Hartman M, Martin AB, Benson J, Catlin A. National Health Care Spending In 2018: Growth

Driven By Accelerations In Medicare And Private Insurance Spending. Health Affairs.

2019;39(1):8-17. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01451.

24. Stange KC. The Problem of Fragmentation and the Need for Integrative Solutions. Ann Fam

Med. 2009;7(2):100-103. doi:10.1370/afm.971.

25. World Health Organization. Declaration of Alma-Ata International Conference on Primary

Health Care, Alma-Ata, USSR, 6–12 September 1978; https://www.who.int/publications/

almaata_declaration_en.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2020.

26. Institute of Medicine. Primary Care: America’s Health in a New Era. Washington, DC:

National Academy Press; 1996. doi:10.17226/5152.

27. Stareld B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of Primary Care to Health Systems and Health.

Milbank Quarterly. 2005;83(3):457-502. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x

28. American Medical Association. AMA Physician Masterle. https://www.ama-assn.org/

practice-management/masterle/ama-physician-masterle. Accessed July 7, 2020.

29. Council on Graduate Medical Education. Twentieth Report: Advancing Primary Care.

Rockville, MD; 2010. https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/les/hrsa/advisory-committees/

graduate-medical-edu/reports/archive/2010.pdf. Accessed July 8, 2020.

30. Makaroff LA, Green LA, Petterson S, Bazemore A. Trends in Physician Supply and

Population Growth. Am Fam Physician. 2013;87(7). https://www.aafp.org/afp/2013/0401/

od3.html. Accessed July 8, 2020.

Primary Care in the United States 39

31. Dall T, Reynolds R, Jones K, Chakrabarti R, Iacobucci W. The Complexities of Physician

Supply and Demand: Projections from 2017 to 2032. Washington, DC: Prepared for the

Association of American Medical Colleges; 2019. https://aamc-black.global.ssl.fastly.net/

production/media/ler_public/31/13/3113ee5c-a038-4c16-89af-294a69826650/2019_

update_-_the_complexities_of_physician_supply_and_demand_-_projections_from_2017-

2032.pdf. Accessed July 7, 2020.

32. Colwill JM, Cultice JM, Kruse RL. Will Generalist Physician Supply Meet Demands Of An

Increasing And Aging Population? Health Affairs. 2008;27(Supplement 1):w232-w241.

doi:10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.w232.

33. National Commission on Certication of Physician Assistants, Inc. 2018 Statistical Prole

of Certied Physician Assistants: An Annual Report of the National Commission on

Certication of Physician Assistants. April 2019. http://www.nccpa.net/research. Accessed

on April 28, 2020.

34. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The Number of Nurse Practitioners and

Physician Assistants Practicing Primary Care in the United States. Rockville, MD. Content

last reviewed September 2018. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/ndings/factsheets/primary/

pcwork2/index.html. Accessed on April 28, 2020.

35. American Academy of Physician Assistants. 2013 AAPA Annual Survey Report. 2014.

https://www.aapa.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/Annual_Server_Data_Tables-S.pdf.

Accessed July 13, 2020.

36. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Women make up most of the

health sector workers but they are under-represented in high-skilled jobs. March 2017.

Available from: https://www.oecd.org/gender/data/women-make-up-most-of-the-health-

sector-workers-but-they-are-under-represented-in-high-skilled-jobs.htm. Accessed April

28, 2020.

37. American Association of Medical Colleges. 2018 Physician Specialty Data Report:

Percentage of Active Physicians Who Are Female, 2017. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/

workforce/interactive-data/2018-physician-specialty-report-data-highlights. Accessed July

8, 2020.

38. Flexner A. Medical education in the United States and Canada. A report to the Carnegie

Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. The Carnegie Foundation, Bulletin Number

Four, 1910.

39. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Health at a Glance 2019: OECD

Indicators. Paris, France; 2019. https://doi.org/10.1787/b33ab4c1-en. Accessed July 8,

2020.

40. Young A, Chaudhry HJ, Pei X, Arnhart K, Dugan M, Steingard SA. FSMB Census of Licensed

Physicians in the United States, 2018. J Med Regul. 2019;105(2):7-23. doi:10.30770/2572-

1852-105.2.7.

41. Liaw WR, Jetty A, Petterson SM, Peterson LE, Bazemore AW. Solo and Small Practices: A

Vital, Diverse Part of Primary Care. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(1):8-15. doi:10.1370/afm.1839.

42. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. Table 2. Cumulative Estimates of Resident

Population Change for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico and Region and

State Rankings: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2018 (NST-EST2018-02). Released Dec 2018.

43. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Fee-For-Service Public Provider

Enrollment Data. Medicare Provider Enrollment, Chain, and Ownership System (PECOS).

https://data.cms.gov/public-provider-enrollment. Accessed July 28, 2020.

44. U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division. Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Resident

Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1,

2019 (NST-EST2019-01). Released date: December 2019.

45. American Community Survey. 2014-2018 ACS 5-Year Estimates. United States Census

Bureau. https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/data/summary-le.html. Accessed

July 20, 2020.

46. Rural-Urban Commuting Area Codes. United States Department of Agriculture: Economic

Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-commuting-area-

codes/. Accessed July 20, 2020.

47. Petterson S, McNellis R, Klink K, Meyers D, Bazemore A. The State of Primary Care in the

United States: A Chartbook of Facts and Statistics. January 2018.

48. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Health Statistics.

Ambulatory Health Care Data. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS). 2016.

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/index.htm. Accessed July 8, 2020.

49. Pourat N, Davis AC, Chen X, Vrungos S, Kominski GF. In California, Primary Care Continuity

Was Associated With Reduced Emergency Department Use And Fewer Hospitalizations.

Health Affairs. 2015;34(7):1113-1120. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1165.

50. Mundt MP, Gilchrist VJ, Fleming MF, Zakletskaia LI, Tuan W-J, Beasley JW. Effects of Primary

Care Team Social Networks on Quality of Care and Costs for Patients With Cardiovascular

Disease. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(2):139-148. doi:10.1370/afm.1754.

51. Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

https://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/. Accessed July 20, 2020.

52. Bazemore A, Petterson S, Peterson LE, Phillips RL. More Comprehensive Care Among

Family Physicians is Associated with Lower Costs and Fewer Hospitalizations. Ann Fam

Med. 2015;13(3):206-213. doi:10.1370/afm.1787.

53. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention

and Health Promotion (NCCDPHP). Chronic Disease in America. Last reviewed October 23,

2019. https://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/resources/infographic/chronic-diseases.htm.

Accessed July 8, 2020.

54. Coutinho AJ, Cochrane A, Stelter K, Phillips RL, Peterson LE. Comparison of Intended