LOCAL GOVERNMENT RECORDS MANUAL

Compiled by the Ohio County Archivists and Records Managers Association (CARMA)

2017

The Ohio History Connection

State Archives of Ohio

Local Government Records Program

800 E. 17

th

Ave.

Columbus, Ohio 43211-2497

www.

ohiohistory.org/lgr

localrecs@ohiohistory.org

614.297.2553

1

Table of Contents

Section I:

Purpose

2

Section II:

Definition of a Public Record

3

Section III:

Why Records Management is Important

4

Section IV:

Records Management and the Law

5

Section V:

The Principles of Record Keeping®

8

Section VI:

Establishing a Records Management Program and Archives

12

Appraisal

12

Accessioning and Processing

13

Organizational Control and Reference Services

14

Storage Facilities

15

Protection of Records

16

Preservation and Conservation

17

Section VII:

Records Retention

18

Inventory

18

Records Life Cycle

19

Appraisal – Records Analysis

20

RC Forms

22

RC Form Review/Approval Process

27

Transferring Public Records

30

Records Management and the Courts

31

Section VIII:

Imaging Records

32

Advantages and Disadvantages

33

Tips and Guidelines

33

Micrographics

34

Disposal of Paper Copies and Scans

35

Section IX:

Electronic Records

36

Authenticity and Reliability

36

Electronic Document Management Systems and Filing Conventions

37

Email

39

Social Media

40

Websites

41

Cloud Computing

42

Litigation Holds, E-Discovery, Disposition, and Sanitation

43

Ohio Electronic Records Committee

44

Section X:

Appendices

Record Series Inventory Form

45

Record Series Analysis Form

46

2

Section I: Purpose

Local Government Records Manual:

Intention and Scope

Local governments create records that must be safeguarded and made accessible to the

public. Ohio’s Public Records Act (1 Ohio Revised Code § 149) includes specific requirements

to make government records more accessible to the people. However, evolving challenges

will require local governments to write and revise policies and procedures to ensure access to

those public records. The purpose of this manual is to educate local government officials on

current methods available for managing public records under their jurisdictions. It provides the

tools to respond to the ever-changing climate of records keeping issues, increase efficiency

and safety, protect historical records, and save resources.

Elements of an effective records management system

All offices have current schedules of records retention and disposition

All public records are accessible to the public and to government entities

Active records stored at site of creation and inactive records are offsite, organized for

retrieval if requested

Permanent and historical records are properly preserved

Policies and procedures created for how to respond to a public records request

All local, state, and federal laws are followed

For additional assistance with records retention principles and other management practices,

please contact the State Archives of Ohio, Local Government Records Program (State

Archives-LGRP).

Ohio History Connection

State Archives

Local Government Records Program

800 E. 17

th

Ave.

Columbus, OH 43211

(614) 297-2553 (phone)

(614) 297-2546 (fax)

www.ohiohistory.org/lgr

3

Section II: Definition of a Record

Public records are subject to review by all individuals upon request. While governments are

obligated to supply public records, the Ohio Revised Code requires all records an office

creates to be maintained through their life cycle and placed on records retention schedules to

prevent unlawful destruction.

1

The Ohio Revised Code, Section 149.011(G) provides three criteria for what materials meet the

definition of a record. To be defined as a record, the item(s) in question must:

Be stored in a fixed medium (e. g. paper, digital image, audio/video)

Created or received during the course of a public office’s business

Document the functions, policies, procedures, activities, and decisions of the public

office

2

Not all materials an office collects, creates, or distributes meet the definition of a record as

noted above. For example, post-its and notes traditionally do not meet the definition of a

record. While the information on the note is on a fixed medium, paper, and it was created as

the result of the office’s business, its content may not always document an office’s function,

policy, procedure, activity, or decision. This is because notes can contain duplicate or general

information that was written for an employee’s personal use.

Examples of Records v. Non-records

Record Non-Record

Meeting Minutes Junk Mail

Drafts Not Yet Officially Adopted Blank Forms

Appointment Calendars Duplicate Copies Within One Office

Records that do not meet all three criteria are considered a non-record and are not subject to

the Ohio Public Records Law. When questioning whether or not an item meets the definition

of a record, please contact legal counsel for clarification.

Whether public or confidential, all documents meeting the definition of a record must be

placed on a records retention schedule. A retention schedule lists the types of records an

office creates, their media format (e.g. electronic, paper, etc.), and the minimum amount of

time they are required to be kept in the office. Records not placed on retention schedules

cannot be legally disposed of. If a public records request is made and the office has never

created a retention schedule that office must supply the requested records even though the

records being requested are past their retention period.

3

For more information on creating

and following a records retention schedule and other forms used to document legal records

destruction, please refer to Section VII.

1

1 Ohio Rev. Code. § 149.351 (2011), available at http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/149.351

2

1 Ohio Rev. Code. § 149.011 (G) (2011), available at http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/149.011

3

1 Ohio Rev. Code. § 149.351 (2011), available at http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/149.351

4

Section III: Why Records Management is Important.

The Ohio Revised Code states local governments must maintain their records throughout their

life cycle. Records need to be identified, defined, and placed on a records retention schedule

in order to prevent unlawful destruction. The act of properly managing your records is more

than simply saying, “It’s the law.” Records management is the foundation for an open,

transparent, government. Records that are being created everyday are important sources of

evidence and serve as justification for the decisions, policies, and procedures by which local

governments function.

Some of the benefits of properly managing your records include:

Space savings. The records that are being created can take up a lot of room. By

implementing a records retention schedule, you may properly dispose of records that

have come to the end of their life cycle. There is no need to have obsolete records

taking up valuable space.

Time savings. Good records management leads to effective filing systems that make

the retrieval of documents faster and easier. Not only does this apply for retrieving

records during the normal course of business, but it also expedites the retrieval of

information in order to fulfill public records requests.

Promotes overall public trust. Local governments ensure accountability by protecting

records from unauthorized alteration, defacement, transfer, and/or destruction.

Improper handling or falsification of public records can result in fines for public

entities.

Documentation of the institutional memory of your local government. Effective

records management ensures that records of enduring historical, legal, or fiscal value

are preserved for future generations to help them understand the history, culture,

people, and decisions of local governments and the individuals they serve.

These are just a few reasons why good records management is important. The proper

management of records offers tangible benefits to local governments that will save valuable

time, money, and resources.

5

Section IV: Records Management and the Law

Public records can and do provide critical evidence for the basic understanding of a

government agency. Identification and maintenance of records is the responsibility of each

agency that generates or receives them.

Records management not only establishes a strong foundation for the efficient management

of records by assisting with their creation, maintenance, retention, and ultimate protection and

preservation or destruction, but is evidence of government being accountable for their actions

and decisions.

Functionally, records management serves two purposes in conjunction with the Ohio Revised

Code. Practicing records management allows offices to organize records for public access

when requested for review.

4

Also, proper records management practices prevent illegal

records destruction.

Records Commissions

All local government entities in Ohio are required by law to establish a Records Commission to

review and approve records retention schedules and one-time records disposal requests

before documentation is sent to the Ohio History Connection for review and approval. The

Commission can also issue rules related to records retention and disposition.

Below are criteria for records commissions:

Counties

[ORC § 149.38]*

Member of the Board of County

Commissioners as chairperson

Prosecuting Attorney

Auditor

Recorder

Clerk of Court of Common Pleas

Meet at least once

every 6 months

Municipalities

[ORC § 149.39]*

Chief Executive (or appointed representative)

as chairman

Chief Fiscal Officer

Chief Legal Officer

Citizen (appointed by the chairman)

Meet at least once

every 6 months

Townships [ORC §

149.42]

Chairman of the Board of Township Trustees

Fiscal Officer of the Township

Meet at least once

every 12 months

School Districts and

Educational Service

Centers (ORC § 149.41]

Board President

Treasurer

Superintendent of Schools

Meet at least once

every 12 months

Public Libraries [ORC §

149.411]

Board of Trustees members

Fiscal Officer

Meet at least once

every 12 months

Special Taxing

Districts [ORC §

149.412]**

Chair of governing board

Fiscal representative from board

Legal representative from board

Meet at least once

every 12 months

4

1 Ohio Rev. Code. § 149.43(B)2 (2011), available at http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/149.43

6

* Counties and municipalities may hire an archivist or records manager and shall appoint a

secretary who may or may not be a member of the commission.

**Special taxing districts that fall completely within a county boundary line may designate the

county records commission as their records commission instead of creating their own. If this

occurs, the special district and county records commission may create a contract defining the

functions being provided to the special taxing district if both parties wish to do so.

After records retention and disposition paperwork has been approved by an entity’s records

commission, the documents are sent to the Ohio History Connection for review and approval.

For more information regarding this process, please see Section VII.

Consequences of Illegal Records Destruction

Records that have met their retention period are legally destroyed by filing disposal paperwork

with the state. Governments are not permitted to destroy records that have not met their

retention period.

5

Records that cannot be produced in response to a public records request can lead to litigation.

Local government entities can be responsible for litigation expenses, statutory damages at a

maximum of $10,000, and may have to pay attorney fees, which is determined by a judge as a

reasonable amount on a case-by-case basis.

Also, if illegal records destruction is suspected by a public office, an investigation may be

conducted to substantiate or dismiss the claims. Offices who have performed such

investigations in the past are local authorities, the Ohio Auditor of State’s Office, and the Ohio

Attorney General’s Office.

When records are illegally destroyed, it can impose heavy administrative hindrances to the

office. Losing needed records can result in offices not being able to fulfill essential job

functions and attempting to recreate lost information on those records can result in the loss of

staff time. This can negatively affect office employees, other government agencies, and the

general public.

The premature loss of records can also reach beyond the administrative functions of an office.

Records that have not gone through proper disposal procedures could result in the loss of

valuable historical information and institutional memory. Lost historical records do not allow

for governments to reflect on past decisions, prevents valuable information from being

discovered to advance historical research and thought, and prevents genealogical researchers

from personally connecting to their past.

5

1 Ohio Rev. Code. § 149.351 (2011), available at http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/149.351

7

Practices to Improve Public Records Access

The Ohio Revised Code requires public offices to perform other duties related to records

management in addition to creating retention schedules and following legal records disposal

practices. These practices serve to improve records access and promote government

accountability.

Public Records Policies

All government offices are required to create and post a public records policy in open public

view. This policy provides procedures for requesting records and costs associated with

requests. The policy must be distributed to individuals in custody of the records of that office

and the receipt must be acknowledged.

6

Sample public records policies are available online on the Ohio Attorney General’s website at

http://www.ohioattorneygeneral.gov/Files/Publications/Publications-for-Legal/Sunshine-Law-

Publications/Model-Public-Records-Policy and the Ohio Auditor of State’s website at

https://ohioauditor.gov/services/opengov/PublicRecordsPolicy85x11.pdf.

Certified Public Records Training

All elected officials or their designees are required by law to attend a Public Records Training

once an elected term. The training is three hours in length and covers the Public Records Law

and Open Meetings Act. Trainings are sponsored by the Ohio Attorney General and Ohio

Auditor of State’s Offices. Information is available on both offices websites,

https://ohioauditor.gov/open/trainings.html and https://sunshinelaw.ohioattorneygeneral.gov.

Optional training covering records management practices, including electronic records, for

local governments is hosted by the Ohio History Connection, State Archives. Information is

available at www.ohiohistory.org/lgrtraining.

Ohio History Connection, State Archives, Local Government Records Program (State

Archives-LGRP)

The Local Government Records Program has staff available to guide local governments with

records retention, maintenance, and disposition and is a division the State Archives at the Ohio

History Connection. Their website at http://www.ohiohistory.org/lgr has manuals and

publications for starting or building a local government records program. The program also

offers trainings to the public.

Ohio County Archivists and Records Managers Association (CARMA)

To aide county governments, the Ohio History Connection worked with county records

managers to create CARMA in 2004. Today, the group meets twice per year to share and

discuss issues related to county records management. More information about the

organization can be found at http://www.ohiohistory.org/carma.

6

Ohio Attorney General, Ohio Sunshine Laws: An Open Government Resource Manual (2016), 62. Available online at

http://www.ohioattorneygeneral.gov/yellowbook

8

Section V: The Principles of Recordkeeping

Effective recordkeeping is essential for the successful operation of any organization. As

records and information management (RIM) programs are developed and maintained within

local governments, it is necessary to develop strategies that will ensure information is

managed correctly. The adoption of best practices in information management assists

organizations in sustaining daily operations, support decision making and document

compliance with applicable laws and regulations. The Association of Records Managers and

Administrators, ARMA International, has developed The Principles® in an effort to assist

organizations in implementing effective record systems and programs. These values are based

on many years of records best practices and they promote a standard of conduct that

represents the processes, roles, standards and metrics that ensure the effective and efficient

use of information.

The Principles are outlined as follows

7

:

Principle of Accountability

The Principle of Accountability ensures that an organization has identified an individual with

the responsibility and authority to design and implement an auditable RIM program. Within a

local government, this individual is often referred to a Records Administrator, Records

Manager or Records Coordinator.

One of the primary responsibilities for the records senior executive is program development.

Compliance needs to be monitored and the overall program should be consistently reviewed

for improvement. Governance needs to be established to assign defined roles and

responsibilities to different staff. The chain of command will support the implementation and

upgrade of the recordkeeping system. It is essential to develop policies and procedures that

will standardize the program across the organization.

To protect the organization and its records while seeking areas for improvement, an audit

program needs to be designed and implemented. An organization’s recordkeeping audits

prove program adherence in accordance with established policies and procedures. Verifying

records are being retained for the right amount of time per the adopted retention schedule

and disposed when their life cycle has been met needs to be audited to ensure compliance.

7

About ARMA International and the Generally Accepted Recordkeeping Principles®

ARMA International (www.arma.org) is a not-for-profit professional association and the authority on information

governance. Formed in 1955, ARMA International is the oldest and largest association for the information management

profession with a current international membership of more than 10,000. It provides education, publications, and

information on the efficient maintenance, retrieval, and preservation of vital information created in public and private

organizations in all sectors of the economy. It also publishes Information Management magazine, and the Generally

Accepted Recordkeeping Principles®. More information about the Principles can be found at

www.arma.org/principles.

9

Principle of Integrity

This principle requires organizational records and information to be reasonably guaranteed as

authentic and unaltered. Authentic records are documents that actually are what they say they

are and are represented to be and are completely free from any additions, deletions or

corruption. Information that exhibits integrity is absolutely critical to the audit process. Overall

confidence in the integrity of records and information within a RIM can significantly increase

with the implementation of this principle.

Business records are strategic and operational assets. The authenticity of those records must

be maintained over a period of time. The recordkeeping system must be reliable to prove the

reliability and integrity of the records. Information management training and direction must be

provided to staff that interact with the system. Staff should be trained as well on the meaning,

importance and usage of recordkeeping policies and procedures.

In efforts to ensure records are created, used and managed in the normal course of business,

organizations must implement consistent recordkeeping practices throughout the records life

cycle. Audit and quality assurance processes must be in place to prove the reliability of the

recordkeeping actions of an organization.

Principle of Protection

This principle relates to the internal controls that protect the integrity of an organization’s

documented information. A Principle-based RIM program will guide management to

incorporate adequate protection to ensure records and information exhibit integrity and

processes and procedures preserve privacy and confidentiality.

It is essential that a recordkeeping program apply the appropriate protection controls to

information from the time it is created and throughout its life cycle until final disposition. All

systems that generate, store and distribute information need to be analyzed to ensure efficient

controls are in place. This applies to both electronic records and physical records. Information

management systems should include a structure where only personnel with a level of security

or clearance can gain access to the information. Protection controls such as key card access

and locked cabinets are measures that can protect physical records from unauthorized access.

Sensitive information must be protected from becoming available or “leaking” outside of an

organization. This can include physical files leaving the premises, electronic files being

downloaded and emailed or information being posted to social media sites. Mechanical

technology controls such as RFID, Radio Frequency Identification, can ensure physical files are

not removed from a records facility. System controls, audits and monitoring social media sites

are options that can assist an organization in safeguarding their records. Final disposition of

records requires the same level of security and confidentiality measures established

throughout its life cycle to ensure the information is protected from being recovered.

10

Principle of Compliance

The principle of compliance delegates that a RIM program manages organizational

information in a manner that satisfies legislative and industry requirements. Maintaining

compliance is a vital component of a RIM program and it is necessary to meet expectations in

an audit. In efforts to be compliant, the Principles of Accountability, Integrity and Protection

must be properly operationalized.

It is every organization’s duty to comply with applicable laws, including those pertaining to the

records management. Recordkeeping systems should support an organization’s activities are

conducted in a lawful manner and that information is being maintained as delegated by law. A

poor recordkeeping program can damage an organization’s credibility and legal standing.

The adoption and enforcement of policies that direct and control the recordkeeping program

are critical to support the internal rule of conduct. A policy imposes a duty of compliance

upon the organization and its personnel.

Principle of Availability

This principle requires that in order for records to be useful they must be available. As

mandated by the Ohio Public Records Law, all public records responsive to the request must

be promptly prepared and made available for inspection to any person at all reasonable times

during regular business hours. Upon request, a public office or person responsible for public

records shall make copies of the requested public record available at cost and within a

reasonable period of time. Section II and Section IV of the Local Government Records Manual

expand upon the definition of a record and the Ohio Public Records Law.

The RIM function is the primary resource within an organization where knowledge of the

organization and location of most of the records and information exists. Information is useless

if it is not available. Successful and responsible organizations have the ability to get the right

information to the right person at the right time. Organization is critical for efficient retrieval

and distribution of information. Recordkeeping systems that capture, maintain and store

information will not be efficient if personnel cannot access records. A properly structured

system with well-designed storage processes and access to understandable, consistent and

relevant information will improve personal productivity, minimize storage costs and optimize

the speed of information retrieval.

Both electronic and physical recordkeeping environments should include effective methods

and tools that will organize information to ensure availability in a timely manner. Policies and

procedural manuals that provide explicit instruction on consistent records management

processes will enhance employee performance. Sufficient training is necessary to successfully

utilize established methods and tools. To sustain ongoing accessibility, electronic information

needs to be routinely backed up for disaster recovery purposes, for system malfunctions and

to avoid the date becoming corrupt. It may also require migration to current supported

software and hardware. Removing unneeded information per the organization’s retention

schedule will reduce maintenance costs of the storage, back up and migration of records.

11

Principle of Retention

The Principle of Retention dictates that records and information are retained through their

useful and/or legal life. As approved by local Records Commissions, the Ohio History

Connection and the Ohio Auditor of State, Schedules of Records Retention and Disposition

identify what records are being retained within an organization and what length of time they

must be retained according to their administrative, legal, fiscal and historical value.

Principle of Disposition

The Principle of Disposition requires that once retention requirements have been satisfied,

records and information will securely and appropriately be deleted. The Principles of Retention

and Disposition define the time-span over which organizational records and information are

available. Through the systematic disposition of records once retention requirements have

been met, organizations will minimize the resources necessary to maintain, retrieve and

analyze information.

Principle of Transparency

This principle supports that a recordkeeping system is accurate and that it represents the

activities of an organization. It dictates that an organization’s RIM policies and procedures

must be understandably documented and that said documents will be available to appropriate

parties. The Transparency Principle will increase confidence in the integrity of auditable

information. This will result in increased speed of a conducted audit which ultimately

decreases overall associated costs.

12

Section VI: Establishing a Records Management Program and Archives

The term “archives” can have three basic meanings:

The noncurrent, semi-active, or inactive records of individual departments/agencies

which are preserved because of their legal, fiscal, administrative, or historical value.

The administrative office or agency responsible for the records should partner with the

center/archives to maintain the records and assist in the workflow process of how the

records will be retrieved and the records final disposition.

The physical building or repository, equipment and supplies necessary to house

records and archival records under specified environmental controls.

Because archival records originate from various offices and agencies, the most efficient way to

manage such a variety of records is to maintain all records with enduring value in a centrally

located archive/repository. Those responsible to retain the records should work with

stakeholders to help champion this concept. The more you involve stakeholders the better

your opportunity to leverage resources and build credibility for the records program.

With all the constraints on local government resources, a good place to start to establish

critical relationships is with the Records Commission. The members of the commission can

assist in providing critical budgetary and staff assistance for a centralized records management

program.

Once there is buy-in for a centralized solution, a good place to start organized records

management is to assign a person in each office to serve as the records officer. Ideally, the

designated staff member will have a working knowledge of the office workflow including how

records are created, how often they are referenced and when they can safely be either

disposed or archived. The designated person should have an opportunity to acquire additional

training in records management and archival techniques.

Archives should perform five basic functions: appraisal, accessioning, processing, and storage

of inactive, permanent records, and reference services for both internal government and the

public. Additionally, archives should have systems in place to ensure organizational control

and protection of records.

Appraisal

Records appraisal consists of determining the value of records. Public records document the

actions and transactions of government and must be retained for varying lengths of time in

accordance with administrative, legal, fiscal, and historical values. Appraisal is the process used

to apply these values to a record and then uses the appropriate retention schedule to decide

how long to keep it. Additional information on records appraisal can be found in Section VII.

13

Accessioning

Records are accessioned when they are transferred from the custody of the creating agency

or department into the care of the archive. This transaction should be documented by both

the sending and receiving agencies. Though records will be in the custody of the archive, they

are still ‘owned’ by the sending agency. Once received, records will be assigned retention

based upon their administrative, fiscal, historical, or legal value and the period of time for

which they will be retained is determined. The accessioning of the records into the custody of

an archive/records center should be documented by a form which may contain the following:

Identification of the office of origin

Date received

Barcode Label (if applicable)

Container Description

Record title and date range

Schedule number (#)

Destruction Date (Review date)

This form must be signed and dated by an authorized official of the transferring department

and accepted by an authorized official of the county archives/records center.

Processing

Archival records will need special care and attention to assure their preservation and usability.

Processing of records accessioned/barcoded into the archives/records center involves

preliminary inspection, arrangement, and description.

When records are ready to be accessioned or transferred, they should be checked regarding

the following:

Are any of the records in urgent need of repair or treatment for water damage, mold

or vermin infestation?

Are the files in archival boxes? Are there file folders within the boxes?

Are the file folders labeled and self-explanatory?

Are the records arranged in some type of order?

Answers to these questions should be noted while completing the accession/transmittal form.

You should note any concerns on this form and provide a copy to the office of origin.

The primary principle of archival arrangement is to maintain the order of records as received

from the office of origin. The initial treatment of records should reflect how the

department/agency handles the functions and actions of the agency that created the records.

This process will assist each agency in working as partners later.

The records of each department/agency should be coded separately, constituting a record

group. Records of administrative units within a major office can be filed as a subgroup, and

individual record series, as listed on appropriate retention schedules, should be arranged under

subgroups. Records may be processed to eliminate extraneous materials such as duplicates

and nonessential materials.

Records should be described and boxes labeled in a way that lets users understand the

contents. Good descriptions ensure the efficient retrieval of records for government and

public records requests.

14

Organizational Control

It is also important to establish a well-organized inventory of the contents of your facility. How

specific the inventory is, is dependent on your needs. The size of the collections and where

you have chosen to have the records stored can impact how you inventory your items as well.

With an in-house facility with several hundred to several thousand cubic feet of storage, a

box/book level inventory with location codes might suffice your needs. If you have chosen to

use an off-site vendor, a more specific item level inventory might fit your needs better as there

will be lack of control regarding the specifics of location codes when using a third party to

store your records.

However you chose to inventory your collection, be consistent with how you inventory.

Depending on your needs, a basic Access Database or Excel Spreadsheet might be sufficient

as these are cost-efficient. For larger institutions that are housing several thousand boxes of

storage, with working with your Data Processing and/or IT department, a homegrown

inventory system might work as you can implement an inventory database to specifically meet

your needs.

Make sure what you are inventorying is marked appropriately and consistent. This can be aided

with a unified box label for all items coming in and out of the facility. Update your inventory

immediately when items get added to the facility or leave the facility so you have a record of

exactly where those records are at all times. This is especially important if you are housing

semi-active files or having items be moved temporarily for imaging/scanning.

Additional information on inventorying records can be found in Section VII.

Reference Services

The archive/records center should include an area with set business hours designated for

public reference. The reference area should be in close proximity to the records allowing for

efficient retrieval of records and easy access for the public.

Reference services are a great benefit to constituents and can be as simple as answering

questions about the content of the materials requested for inspection. A person should be

designated to retrieve records for examination by patrons. If you have monetary issues, you

might consider working with organizations in your community that would consider

volunteering. You could also look at creating an accredited internship program that would

assist the records center/archives.

Create a policy that governs the handling of records from the storage area. The policy should

address restrictions on the handling of records by visitors. Examples of items to be covered

include that there will be no food, beverages, or smoking in the archive/records center.

Additionally, no records should be allowed to be removed from the reference area. Fees for

copies should be set by the appropriate authority. A daily log of who has visited and

referenced materials from the records center/archives should also be maintained.

15

Storage Facilities

It is neither practical nor possible to keep every record created or received within the confines

of most offices. Office space should contain only those records necessary for conducting daily

business effectively. Alternative methods of storage are needed for the maintenance of

records that must be kept for administrative, legal or fiscal reasons, but are not referenced

regularly — i.e., semi-current or inactive records. Many of these records will be disposed of

directly from the office due to their shorter retention period. Others require storage long after

removal from the office. These records, especially those with extended retention periods or

records kept permanently for historical value in their original format, require special storage

conditions so that they will not rapidly deteriorate or suffer damage from fire, flood,

infestation, or theft.

If large quantities of records are to be stored and a separate records center or archives is not

available, it is necessary to dedicate a specific area to serve as a records center or records

room. With proper care, this storage area will protect records from deterioration caused by

excessive heat and humidity or by vermin infestation. With proper safety precautions, stored

records will be relatively safe from fire, flood, or theft.

Records that are to be stored for extended periods require special storage conditions to avoid

rapid deterioration or damage from fire, flood or theft. An ideal storage area will include

temperature and humidity controls to keep the facility cool, dry and constant. Temperatures

should range between 60 – 70 degrees Fahrenheit. Humidity should be between 40-50%. The

storage area should be equipped with metal shelving 4-6 inches above the floor level.

Records should be contained in standard sized storage boxes in a cool, dry, and fire-resistant

room that can be kept locked against unauthorized entry. Boxes should be packed as if they

were file drawers, in the same order in which they were maintained and not over-packed.

Microfilm should be stored in metal microfilm storage cabinets. Fire alarms and extinguishers

and an intrusion alarm system are part of an ideal records storage area. Many localities cannot

provide the “ideal environment” to house records, but efforts should be made to meet as many

criteria as possible.

Vital records, those essential to the continued operation of an agency in case of emergency,

require the safest and most secure storage area possible, preferably in a building separate from

the office operation. Similarly, security copies of microfilm must be kept in a separate location

as stated in Ohio Revised Code § 9.01:

“… when recording or making a copy or reproduction of any such record, for the

purpose of recording or copying, preserving, and protecting them, reducing space

required for storage, or any similar purpose… the duplicates shall be stored in different

buildings.”

8

While this highlights typical hardcopy/physical media, it is also important to make sure that

you are maintaining your electronic media in a similar way. The EDMS (electronic document

management system) must be maintained in similar conditions as your

paper/tape/micrographics storage facility, on a server located in a secure, dry, and fireproof

location.

State Law 1 Ohio Revised Code § 149.43 requires that all public records be made available for

inspection to the public during regular business hours. Well-planned and orderly records

storage will facilitate compliance with this statutory requirement.

8

Ohio Rev. Code §9.01 (2011), available at http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/gp9.01v1

16

Protection of Records

The statutory requirement to preserve and make available the records of a public office

necessitate care is taken to protect public records. The following precautionary considerations

are taken from the New Jersey Records Manual, 2013 Revision

9

:

Fire

Records storage areas should minimize exposure to losses from accidental fire by

prohibiting smoking in the building and segregating combustible materials from

records content. Well-appointed records areas have automatic sprinklers, smoke

detection systems, fire doors and walls, and electrical wiring in metal conduit – all of

which are inspected periodically by general building and fire code officials.

Vermin and Contamination

Records storage areas should offer protection against damage from vermin and

environmental contamination. The organic substances in leather, pastes, and paper are

a good source of food for vermin. Accumulated dust and debris provide a haven for

the growth of insects and mold. Prevention measures depend upon the nature of the

pestilence and include keeping the building clean, as well as conducting periodic

exterminations and installing filtration for insects and fungus spores, if needed.

Temperature and Humidity

Records storage areas should provide environmental controls and inspection regimes

that guard against extreme fluctuations of temperature and humidity that hasten

records deterioration. Periodic inspections of the storage facility include monitoring

for plumbing leaks, standing water, and excess humidity. Records storage boxes may

be examined randomly for mold, infestation, or other signs of deterioration. An ideal

records storage area will have temperature and humidity controls that maintain 40%-

50% relative humidity and a temperature range of 60° – 70° Fahrenheit. The controls

should be set to prevent excessive and short-term fluctuations in temperature and

humidity. This storage area should be equipped with fireproof shelving, standard-sized

storage boxes, fire alarms and extinguisher, and an intrusion alarm system. If microfilm

is to be stored, the area should also have appropriate fire/humidity proof microfilm

cabinets. Inexpensive exhaust fans and portable dehumidifiers will help to maintain an

environment suitable for records storage.

Access Control and Physical Security

Only authorized staff members are allowed to access records stored in a records

storage center. Staff should maintain lists or registries of persons to whom records

may be released. Other security controls include video monitors, guards at stations

and on patrol, key card access (for authorized personnel only), central station intrusion

detection and alarm systems, and separate locks on all doors.

9

New Jersey Department of the Treasury, New Jersey Records Manual, chapter 3 (2013). Available online at

http://www.nj.gov/treasury/revenue/rms/RecordsManual.shtml

17

Preservation and Conservation

While most government records are in acceptable condition and maintained with diligence,

some records could be affected by adverse conditions which could hasten deterioration. Extra

emphasis should be placed on permanent/historical records that meet these criteria.

The main difference between preservation and conservation is that preservation strives to

prevent or slow down deterioration to records, whereas conservation is the use of treatments

to reverse damage to documents.

Preservation techniques include providing proper environmental controls, lighting, shelving,

boxes and folders. It can also include processing procedures such as removing paperclips and

staples or flattening documents. Microfilming and digitization can also be considered

preservation methods. Filming preserves older, deteriorating documents by generating durable

working copies for researchers as well as archival master copies for permanent storage, which

ensures access while protecting the original document. Fragile records can also be sleeved or

encapsulated using Mylar or other polyester film. This is not the same as laminating, which

should not be done, but rather creates a loose protective enclosure that can be removed if

necessary.

Conservation involves repairing and mending documents or removing adhesives.

Conservation techniques require knowledge and experience in order to ensure that their

application does not unwittingly hasten deterioration and should only be performed by a

trained conservator. If there is a need for conservation, local officials with assistance from

records manager should look for a private vendor to apply conservation techniques.

10

If moldy or insect-infested records are identified, they should be segregated from the

archive/records center to avoid contamination of other records. The Northeast Document

Conservation Center (NEDCC) is a nonprofit organization that publishes great resources for

dealing with issues like these. Their online preservation leaflets contain step by step

instructions for records emergency management.

11

Routine inspections of records can detect

potential problems.

10

John H. Slate & Kaye Lanning Minchew, Managing local government archives. (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield,

2016), 54.

11

Northeast Document Conservation Center, Preservation Leaflets. Available online at https://www.nedcc.org/free-

resources/preservation-leaflets/overview

18

Section VII: Records Retention

Establishing a records management program may seem like an overwhelming task, but

following the process below will get a local government on the right path in a few easy steps.

Inventory

Proper records management begins with a records inventory. An inventory should be done if

the agency has never worked on records management or has not revisited their plan in several

years. Inventories allow agencies to identify what records are created and stored (e.g. types,

formats, etc.), where they store them, and how often they reference them. This information

helps create a useful retention and disposition schedule. Inventory forms should not be

submitted to the State Archives-LGRP.

Records are categorized as “records series” during an inventory. A records series is defined as

“a group of similar records that are arranged according to a filing system and that are related

as a result of being created, received, or used in the same activity

12

.” Examples of records

series include committee minutes, purchase orders, executive correspondence, etc.

An inventory may seem like a daunting task, but the concept of a records series should help

dispel anxiety. The level of detail necessary to survey every single record is not necessary for

an inventory. Records are considered as a part of a larger group (i.e. the records series) instead

of individually, which eliminates the need to document the specific details of every record.

Several pieces of information need to be collected while performing a records inventory. The

Records Series Inventory Form (Appendix A) can be used to effectively collect and synthesize

this information. When identifying a record series address these questions: 1) are these records

filed together, 2) do these records have a common purpose, and 3) are they needed for the

same time period. When a records series is identified, the department where it originates

and/or is used should be recorded, the series should be given a name and a definition. If the

records series was previously scheduled the schedule number and date of records

commission approval should also be included. It is also a good idea to indicate whether the

record series is still being created or not. The arrangement (e.g. alphabetical, chronological, by

case number, etc.), inclusive dates, volume, location, and media types also need to be

included. Other pieces of information may be worth collecting as well, for example: the

individual responsible for these records, physical condition, rate of accumulation, how often

they are accessed, when they stop being accessed, any legal considerations, date of inventory,

if they are considered vital records, whether this department’s version is the record copy or the

use copy, recommended retention period, etc.

Another essential aspect of a records inventory is interviews with the staff who work with

particular records series. These conversations help uncover the general purpose and function

of the records series. They also can highlight any areas of concern that might be addressed by

a useful retention and disposition schedule. You may also want to designate a records officer

for each department before or during a records inventory.

The data collected in a records inventory is not limited in value to creating a retention and

disposition schedule. It can help determine when certain records series should be moved to

offsite storage (or if any should be returned), it may point out problems with

12

Richard Pearce-Moses. A Glossary of Archival and Records Terminology. (Chicago: The Society of American

Archivists, 2005), 338. Available at http://files.archivists.org/pubs/free/SAA-Glossary-2005.pdf.

19

retrieval/completing public records requests in a timely fashion, and it may allow an agency to

see an opportunity to take advantage of scanning, microfilming, or other duplication methods

in order to deal with storage and/or preservation concerns.

Records Life Cycle

Doing a records inventory will give you some insight into the records life cycle. The records

life cycle is defined as “the distinct phases of a record’s existence, from creation to final

disposition

13

.” There are several different records life cycle models, but they all contain stages

for creation/receipt, use, and disposition. The model may also distinguish between active and

inactive records. A record is first created/received and then used or referred to by the creating

office or by others. Then the record is determined to have met its useful life and been

disposed, retained permanently, or it is placed into storage where it may be inactive but still

necessary for the office. After storage a record may then face disposition or it may be retained

permanently either in the office, off-site, or, perhaps, at a new repository (e.g. local historical

society, public library, etc.). It is as important to dispose of records in a timely fashion as it is to

appropriately retain public records. The records life cycle makes this clear; otherwise useless

records become an unnecessary burden. Retaining records beyond their retention causes

local governments to spend money on storage, equipment, and supplies. Active records may

become harder to access due to an accumulation of records that have met their useful life

span. Huge stacks of records can be physically dangerous and pose safety threats.

Understanding the natural progression in the usefulness of a record plus the knowledge

gained in the inventory will help accomplish the next task: appraisal.

13

Pearce-Moses, 232.

20

Appraisal—Records Analysis

Once a records inventory is completed the various values associated with records need to be

evaluated in order to determine appropriate retention periods. This process is called “appraisal”

or “evaluation.” Evaluation is determining the value of records in regards to the records life

cycle. This is different from archival appraisal, which concerns whether a record is worth

permanent preservation in an archive or special collection, and from monetary appraisal.

There are four basic values that need to be assessed for each record series: administrative,

fiscal, legal, and historical.

Administrative Value - Use in carrying out an agency’s functions (Check with the

records creators)

Fiscal Value - Pertains to the receipt, transfer, payment, adjustment, or encumbrances

of funds; may be required for an audit (Check with the auditor, fiscal officer, etc.)

Legal Value - Documents or protects rights or obligations of citizens or of the agency

that created it; retain until all legal rights and obligations expire (Check with legal

counsel)

Historical Value - Documents an agency’s organization, policies, decisions,

procedures, operations, and other activities; contains significant information about

people, places, or events and may have secondary value as a source of information for

persons other than the creator (Check with the State Archives-LGRP)

The Record Series Analysis Form (Appendix 2) can help collect this information. It asks specific

questions about how often records are used, what would happen if they were no longer

available, how often audits are conducted, what Ohio Revised Code or Federal laws regulate

the records, if they are exempt from disclosure, if they contain necessary redactions before

disclosure, and whether there is any informational content that could be considered historical.

All records series will have administrative value, but not all records series will have the other

three values. Often there will be a combination of appropriate values.

Analyzing the four values will give you the minimum amount of time each record series needs

to be retained for each value. The retention period of a record series should be set based on

the value with the longest minimum amount of time necessary for retention. For example, an

agency may have a contracts record series that is necessary in the office until the contracts

expire (administrative value), necessary for an audit (fiscal value), and for which the statute of

limitations expires eight years after expiration per the Ohio Revised Code (legal value). The

retention period for this contracts record series should be set at “eight years after expiration.”

Retention periods can be expressed in one of three ways:

Time (e.g. 3 years, permanent, etc.)

Event/Action (e.g. until audited, until no longer of administrative value, etc.)

Combination (e.g. 3 years after case is closed, 8 years after expiration, etc.)

They can also be divided based on storage location or media type. For example, “retain in

office for 3 years, move to offsite storage and retain for 7 more years, then dispose” or “retain

paper version until scanned and quality control checked, then dispose; retain electronic

version for 10 years.”

During this procedure a local government may also consider all the copies, drafts, voicemail

messages, quick emails about changes in meeting locations, etc. that offices create or receive.

These types of records are called “transient” or “transitory.” They only have modest

administrative value. Usually they communicate information of temporary importance in lieu

of oral communication. While these records can be public records and they should be

21

properly scheduled on the RC-2 form, they need not be retained long term. The State

Archives-LGRP suggests that transitory records are scheduled as follows:

Schedule Number Record Series Title &

Description

Retention Period Media Type

#### COPIES OF RECORDS

Additional copies of

records or images

which are no longer

required and serve no

useful purpose.

Until no longer of

administrative value.

Paper/Electronic

#### DRAFTS/TRANSIENT

RECORDS

Preliminary working

documents and other

documents which

serve to convey

information of

temporary importance

in lieu of oral

communication.

Until no longer of

administrative value.

Paper/Electronic

It is important to remember that retention periods are not static. They change as laws and

business practices change. For example, the statute of limitations for contracts set in the Ohio

Revised Code changed from fifteen years to eight years, allowing the retention period for

contracts to shorten due to a change in their legal value. Remember to stay abreast of

legislation that will affect your records as well as making sure to alter retention periods as your

local business practices/procedures change.

22

The RC Forms

The RC forms are a standardized way for local governments in the state of Ohio to collect,

submit, and file the information necessary to be in compliance with the Public Records Law.

There are three different forms: Records Retention Schedule (RC-2), Certificate of Records

Disposal (RC-3), and One-Time Disposal of Obsolete Records (RC-1). Word and PDF versions

of these forms can be found on the State Archives-LGRP website.

Records Retention Schedules (RC-2)

The Records Retention Schedule (RC-2) is the basis of a local government’s records

management program. It lists all ongoing records series with appropriate retention periods and

media types. Proper scheduling of records series on an RC-2 allows for the legal disposal of

public records. An accurate RC-2 allows a local government to negotiate public records

requests as well.

Part 1 of the RC-2 form contains the signatures that authorize the retention schedule. Section

A should be filled out with the contact information for the department and contains the

signature of the responsible official. Section B should be filled out with the contact information

for the local records commission and the signature of the chairperson. The chairperson’s

signature certifies that the RC-2 was approved in an open meeting of the records

commission

14

. Section C has a signature from the reviewing party at the State Archives-LGRP

and Section D has a signature from the reviewing party at the Auditor of State’s office. All four

signatures must be present on the RC-2 form to make it valid.

In Part 2 Section E of the RC-2 form the retention schedule is laid out. It includes a unique

schedule number for each record series in column 1. Schedule numbers are a way of

organizing and labeling your records boxes/electronic folders in order to have more

intellectual control over your records. Labeling boxes and electronic folders with schedule

numbers allows the records manager to quickly identify the contents without having to rifle

through the papers or open up the folder on the server. Schedule numbers can be created in

the way that makes the most sense locally. Many local government agencies generate them

using acronyms related to the relevant department (e.g. HR-001, HR-002, ADM-035, ADM-

036, etc.). Other local governments create entirely numeric schedule numbers, often based on

the fiscal year of the creation of the RC-2 form (e.g. 2013-001, 2013-002, 2014-035, 2014-

036, etc.). Make sure there is a consistent system in place in order to avoid duplicate schedule

numbers and confusion between departments.

RC-2 forms also include the record series title and description, which were created during the

inventory, in column 2. The description is important because, while a record series’ contents

may seem obvious to the records creator, a member of the public may not understand what is

being scheduled and that knowledge might not be obvious to a subsequent person filling that

position in the office. It is also helpful to the State Archives-LGRP when reviewing the RC-2

form to understand exactly what pieces of information are found in any given records series.

Column 3 of the RC-2 form records the retention period. Retention periods should be

expressed by time, an event/action, or a combination of the two. Make sure that media types

are separated within the same record series if they have different retention periods. Media type

is recorded in column 4. Please leave column 5 blank; the State Archives-LGRP will use

14

1 Ohio Rev. Code §121.22 (2011), available at http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/121.22

23

column 5 to make any clarifying notes. The State Archives-LGRP will also use column 6 to

mark which records series require a Certificate of Records Disposal (RC-3) prior to disposal,

which will be discussed below.

Part 2 of the completed retention schedule should look like this:

24

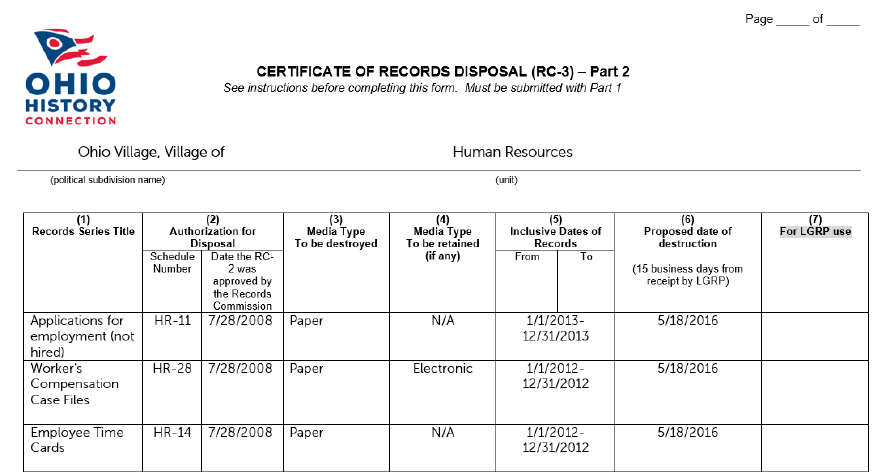

Certificates of Records Disposal (RC-3)

The Certificate of Records Disposal (RC-3) is the form which is used to propose the disposal of

records belonging to ongoing records series which have been properly scheduled on an RC-2

form. The RC-3 form only needs to be used for records series which have been marked by the

State Archives-LGRP as requiring an RC-3 prior to disposal for RC-2 forms which were signed

on or after September 29, 2011 by the local records commission chairperson. If the RC-2

predates September 29, 2011 please submit an RC-3 to the State Archives-LGRP for all records

series. The State Archives-LGRP strongly suggests that a permanent and internal record of all

public records disposals is maintained by the local records commission regardless of whether

the RC-3 form is required to be submitted or not.

The first page of the RC-3 form contains the contact information and authorization signature

from the responsible official. The signature certifies that the records listed on the RC-3 form

have met the respective retention periods based on approved RC-2 forms and that none of

the records proposed for disposal are relevant to any pending litigation/complaint. The RC-3

form only requires the signature of the responsible official and does not require the signature

of the chairperson of the records commission.

The second page of the RC-3 is where records are proposed for disposal. Column 1 contains

the record series title. It should be the same title found on the approved RC-2 form. Specific

information about case numbers, employee names, etc. does not need to be included.

Column 2a contains the appropriate schedule number for that record series title. The schedule

number should match the schedule number found on the approved RC-2. Column 2b

contains the date the RC-2 on which this schedule number is found was approved by the local

records commission. It is not the date the RC-3 was reviewed by the local records

commission. This date helps the State Archives-LGRP verify that approved retention periods

are being followed and allows the State Archives-LGRP to locate the appropriate RC-2 for that

verification. Column 3 records the media type which is proposed for disposal. Column 4 only

needs to be used if the record is being maintained on a different media type than the one

proposed for disposal. Column 5 lists the inclusive dates of the records proposed for disposal.

Please provide dates that are as specific as possible. Try to avoid phrases like “prior to,” “up to,”

“after,” etc. It is best to provide month and year information (e.g. 4/2008 through 3/2012). If

only years are provided the State Archives-LGRP will assume that the entire calendar year is

proposed for disposal. Dates help the State Archives-LGRP appraise the records for possible

historical value and enable the local government to fully document disposal. Please provide

the proposed date of destruction in column 6. This date must be at least 15 business days after

the State Archives-LGRP receives the RC-3 for review. The State Archives-LGRP will use

column 7 to make any clarifying notes or to mark records for possible transfer.

Note that with the passage of House Bill 153 by the 129

th

General Assembly, if your Records

RC-2 was signed by your local records commission after September 29, 2011, RC-3 forms will

only be required for records series indicated by State Archives-LGRP on your RC-2 form. If the

record series indicates that an RC-3 is required or if your RC-2 was signed on or before

September 29, 2011, an RC-3 is required before records are destroyed. The Local Government

Records Program has 15 business days to review the RC-3. Please contact the State Archives-

LGRP if you wish to dispose of a record that is more than 50 years old, even if the RC-2 does

not require a RC-3. While the age of a record is not the only factor that determines historical

value, in general, records that are 50 years old or older are more likely to have historical value.

We suggest that your local records commission continues to document the disposal of

records series internally. The local records commission can decide if they would like to receive

an RC-3 from a department/agency if one is not required by the State Archives-LGRP.

25

Part 2 of the completed RC-3 should look like this:

26

One-Time Disposal of Obsolete Records (RC-1)

The One-Time Disposal of Obsolete Records (RC-1) is the most difficult form to understand

and it should be used the least. RC-1 forms are used to propose the disposal of obsolete

records. Obsolete records are records that have never been properly scheduled on an RC-2

and are no longer created or were only created once. Records inventories often help local

governments discover obsolete records. If obsolete records are found and they no longer

have any administrative, fiscal, legal, or historical value they should be listed on the RC-1 form

and proposed for disposal. RC-1 forms are also used to document any early destruction of

records due to disaster as well as document records transfers. If there are any questions about

the appropriateness of the RC-1 form, please contact the State Archives-LGRP.

The first page of the RC-1 form is exactly the same as Part 1 of the RC-2 form. The second

page is where the obsolete records are listed for review prior to disposal. In column 1 please

provide a schedule number for each record series proposed for disposal. This can seem

confusing because a schedule number should not already exist for them and creating one

seems unnecessary since they will not require management once they are disposed. A simple

numbering down the list is sufficient here (e.g. 1, 2, 3, etc.) or even incorporating the RC-1

designation can work (e.g. RC1-001, RC1-002, etc.). Column 2 lists the records proposed for

disposal with a brief description and the inclusive dates. This information is vital to helping the

State Archives-LGRP appraise these records for possible historical value, so please be as

detailed as possible. Column 3 lists the media type to be disposed and column 4 lists any other

media types on which this record is being maintained. Please leave column 5 empty; the State

Archives-LGRP will use this column to make any clarifying notes or mark records for possible

transfer.

Part 2 of the completed RC-1 should look like this:

27

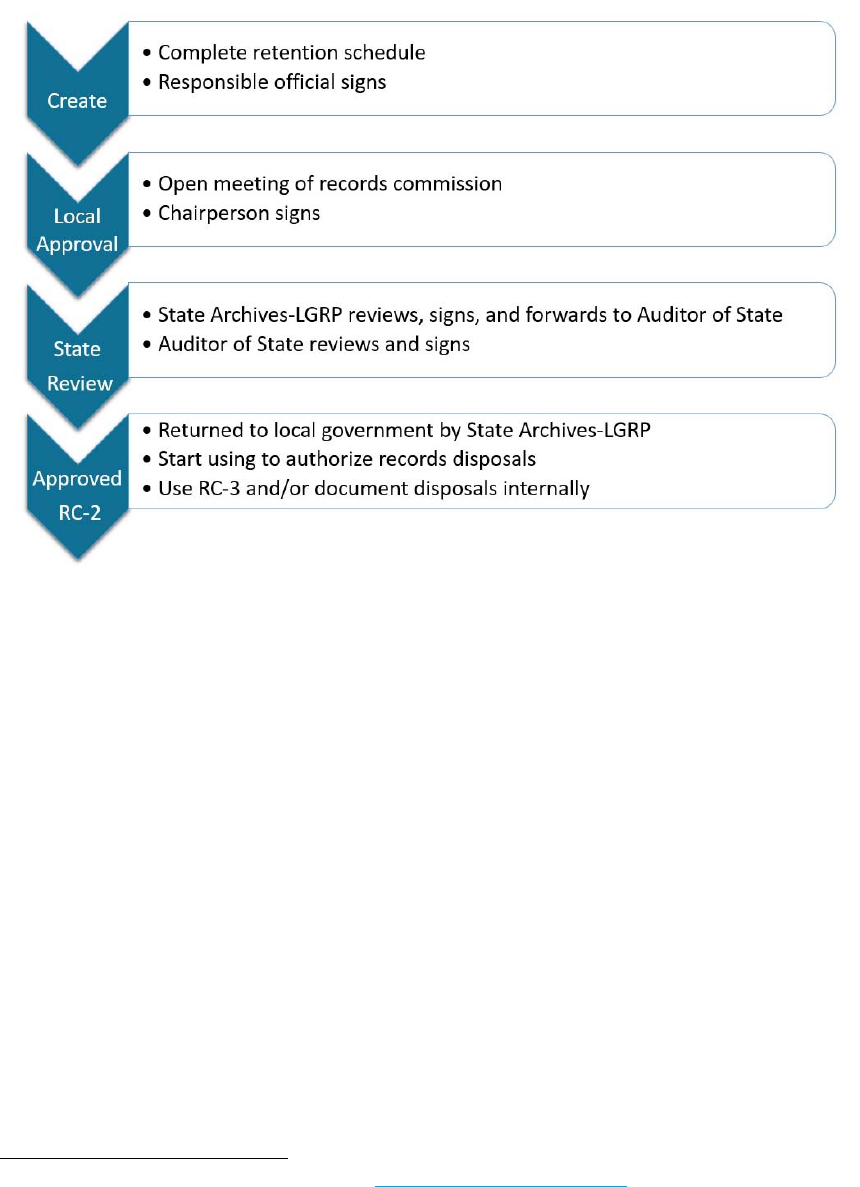

The RC Form Review/Approval Process

The RC form review and approval process can seem intimidating at first, but there are only a

couple of steps that a local government needs to remember. The processes for RC-2 and RC-

1 forms take the same amount of time and are very similar. RC-3 forms are processed within

fifteen business days.

RC-2 Review/Approval Process

Once the retention schedule has been compiled on the RC-2 (Section E) it is ready to begin

the review and approval process. It should first be signed by the responsible official for the

appropriate department in Section A. That signature means that the RC-2 is ready to be

discussed in an open meeting of the local records commission. Different records commissions

have different requirements on how often they are required by statute to meet; please consult

the Sunshine Laws Manual produced by the Ohio Attorney General’s office for more details

regarding records commission rules and rules concerning the Open Meetings Act. The

Sunshine Laws Manual can be found on the Ohio Attorney General’s website as a searchable

PDF. After the local records commission has discussed the RC-2 at an open meeting and

approved its contents, the chairperson must sign the RC-2 in Section B.

Those two signatures mean that the RC-2 is ready to be reviewed by the State Archives-LGRP.

Local governments can fax, mail, or email the signed RC-2:

Ohio History Connection

Attn: Local Government Records Program

800 E. 17

th

Ave.

Columbus, OH 43211

(614) 297-2546 [fax]

Only send the signed RC-2 to the State Archives-LGRP; it does not need to be sent to the

Auditor of State’s office at the same time. The State Archives-LGRP will forward it to the

Auditor of State’s office at the appropriate time.

State Archives-LGRP has 60 days to review an RC-2

15

. Records series which will require an

RC-3 prior to disposal will be marked by the State Archives-LGRP. During that time the State

Archives-LGRP may contact the local government for more information concerning the

records listed. There may also be issues with the retention schedule that require it to be sent

back to the originating department for revisions. The State Archives-LGRP will communicate

with the local government concerning all issues and questions. When the RC-2 is determined

to be sufficient by the State Archives-LGRP it will be signed and forwarded to the Auditor of

State’s office for approval.

The Auditor of State’s office also has 60 days to review an RC-2

16

. The total review process can

take up to 120 days. After the Auditor of State’s office has signed the RC-2 form they will send

it back to the State Archives-LGRP. The State Archives-LGRP will retain the RC-2 permanently.

A copy will be made and returned to the local government in the manner requested. If an

email address is provided in Section B of Part 1, the signed and approved RC-2 will be returned

as a PDF via email. If no email address is provided, a hardcopy version will be sent back to the

15

1 Ohio Rev. Code §149.381 (B) (2011), available at http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/149.381

16

1 Ohio Rev. Code §149.381 (B) (2011), available at http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/149.381

28

records commission via mail. Only one method will be utilized. The RC-2 is in effect once it

has all four signatures and has been returned to the local government.

The review process for RC-2 forms is as follows:

RC-3 Review/Approval Process

The RC-3 form can only be used if there is an approved RC-2 on file at the State Archives-

LGRP. After an RC-2 is completely signed and returned by the State Archives-LGRP it can be

used to authorize the disposal of the listed records series. Use the RC-2 to determine which

records series have met their retention periods and are eligible for disposal. If any records

series require an RC-3 prior to disposal (only on RC-2 forms signed on or after September 29,

2011) please complete the RC-3 form and submit it at least 15 business days before your

proposed date of disposal. The RC-3 form only needs to be signed by the responsible official

before being sent to the State Archives-LGRP. They can be sent via fax, postal mail, or email. If

a record series does not require an RC-3 form prior to disposal, please document the disposal

internally. It is the decision of the local records commission if they want to be notified before a

disposal. If a record series does not require an RC-3 form prior to disposal per the State

Archives-LGRP, contact your local records commission regarding if they request to review the

disposal. Please remember that all records series scheduled on RC-2 forms that were

approved prior to September 29, 2011 require RC-3 forms before disposal.

The State Archives-LGRP has 15 business days to review an RC-3

17

. During the review period

the State Archives-LGRP may contact the local government with questions about the records

proposed for disposal. Sometimes the State Archives-LGRP will contact the local government

about the possibility of transferring some of the records. In the event of a transfer the State

Archives-LGRP will guide a local government through the process. If there are no issues with

17

1 Ohio Rev. Code §149.381 (D) (2011), available at http://codes.ohio.gov/orc/149.381

29

the RC-3 form or they were resolved through phone calls and emails, the reviewing party from

the State Archives-LGRP will initial the RC-3 form. The RC-3 will be filed at the State Archives-

LGRP.

Local governments do not receive notice or a copy of the initialed RC-3 form. If they do not

hear from the State Archives-LGRP within the 15 business day review period they are free to

dispose of the records listed on the RC-3 form on their proposed date of disposal. Copies of

initialed RC-3 forms can be sent to the local government if requested in one of two ways: 1)

send in two signed RC-3 forms with a self-addressed, stamped envelope or 2) provide an

email address near the signature line on the RC-3 form.

The review process for RC-3 forms is as follows:

RC-1 Review/Approval Process

The review and approval process for the RC-1 form is the same as the process for the RC-2

form. The only difference is that when a local government receives the signed, approved RC-1

back from the State Archives-LGRP they may proceed with the disposal of the listed records

without filing an RC-3 form. Review and approval of the RC-1 form by the local records

commission, the State Archives-LGRP, and the Auditor of State’s office authorize the disposal

of the records listed. The State Archives-LGRP does suggest that a permanent and internal

record of disposals based on RC-1 forms be retained by the local records commission. An easy

way to follow this suggestion is to retain RC-1 forms permanently.

The review process for RC-1 forms is as follows:

30

Transferring Public Records

The inventory or RC form review and approval process may reveal records that could be better

served by being transferred. In Ohio public records can only be transferred by written

agreement to public or quasi-public institutions

18

. The State Archives-LGRP works to facilitate

these transfers to local historical societies, local genealogy societies, local public libraries,

members of the Ohio Network of American History Research (ONAHR) Centers, or the State

Archives, which is a member of the ONAHR Centers. As the archives administration for the

state of Ohio, the Ohio History Connection organized the ONAHR Centers in 1970 to provide

for the preservation of historically valuable local government records. Composed of four state

universities and Ohio's two largest historical societies, the network members preserve and

make available all forms of documentation relating to Ohio's past.

The State Archives-LGRP will initiate the process if records that are thought to be of enduring

historical value and worth transferring are found during the review of RC forms. Often records

worth transferring are found by the local government during an inventory or through the

normal course of business. Sometimes a relationship with a local institution provides an

opportunity for records transfer. In these cases, please contact the State Archives-LGRP to

discuss the transfer before proceeding. There are some records that should not be transferred

because of rules exempting them from disclosure

19

. For example, records containing

personally identifiable information about any student beyond what is considered “directory

information

20

” should not be transferred

21

.

Transfers to local historical societies, local genealogy societies, and local public libraries