30 October 2023

ESMA50-524821-2954

0

ESMA TRV Risk Analysis Orderly Markets

Evolution of EEA share market

structure since MiFID II

ESMA TRV Risk Analysis 30 October 2023 2

ESMA Report on Trends, Risks and Vulnerabilities Risk Analysis

© European Securities and Markets Authority, Paris, 2023. All rights reserved. Brief excerpts may be reproduced or translated provided the source

is cited adequately. The reporting period for this Report is 1 January 2019 to 31 December 2022, unless otherwise indicated. Legal reference for

this Report: Regulation (EU) No. 1095/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 November 2010 establishing a European

Supervisory Authority (European Securities and Markets Authority), amending Decision No 716/2009/EC and repealing Commission Decision

2009/77/EC, Article 32 ‘Assessment of market developments, including stress tests’, ‘1. The Authority shall monitor and assess market developments

in the area of its competence and, where necessary, inform the European Supervisory Authority (European Banking Authority), and the European

Supervisory Authority (European Insurance and Occupational Pensions Authority), the European Systemic Risk Board, and the European

Parliament, the Council and the Commission about the relevant micro-prudential trends, potential risks and vulnerabilities. The Authority shall include

in its assessments an analysis of the markets in which financial market participants operate and an assessment of the impact of potential market

developments on such financial market participants.’ The information contained in this publication, including text, charts and data, exclusively serves

analytical purposes. It does not provide forecasts or investment advice, nor does it prejudice, preclude or influence in any way past, existing or future

regulatory or supervisory obligations by market participants. The charts and analyses in this report are, fully or in part, based on data not proprietary

to ESMA, including from commercial data providers and public authorities. ESMA uses these data in good faith and does not take responsibility for

their accuracy or completeness. ESMA is committed to constantly improving its data sources and reserves the right to alter data sources at any time.

The third-party data used in this publication may be subject to provider-specific disclaimers, especially regarding their ownership, their reuse by non-

customers and, in particular, their accuracy, completeness or timeliness, and the provider’s liability related thereto. Please consult the websites of

the individual data providers, whose names are given throughout this report, for more details on these disclaimers. Where third-party data are used

to create a chart or table or to undertake an analysis, the third party is identified and credited as the source. In each case, ESMA is cited by default

as a source, reflecting any data management or cleaning, processing, matching, analytical, editorial or other adjustments to raw data undertaken.

PRINT ISBN 978-92-95202-87-0, doi :10.2856/574362, EK-05-23-306-EN-C

PDF ISBN 978-92-95202-88-7, doi :10.2856/982068, EK-05-23-306-EN-N

European Securities and Markets Authority (ESMA)

Economics, Financial Stability and Risk Department

201-203 Rue de Bercy

FR-75012 Paris

risk.analysis@esma.europa.eu

ESMA - 201-203 rue de Bercy - CS 80910 - 75589 Paris Cedex 12 - France - www.esma.europa.eu

Cover photo: Image Microsoft 365

ESMA TRV Risk Analysis 30 October 2023 3

Orderly Markets

Evolution of EEA share market

structure since MiFID II

Contact: caroline.le[email protected]pa.eu

1

Summary

Since the launch of the EU capital markets union initiative, new legislative and non-legislative proposals

have aimed at fostering a single market for capital in the EU. These regulatory proposals, together with

other external events including mergers, have shaped the integration and competition level of trading

platforms. Making use of regulatory data, this article presents the evolution of the European share

market microstructure from 2019 to 2022, with a specific focus on the impact of the UK’s withdrawal

from the EU, given its pivotal role in equity markets. The important decrease in trading volumes

observed after 2021 was accompanied by four main changes: a decrease in the number of

infrastructures trading shares, even though they remain elevated; a new distribution of trading, both by

market type and by country, with a concentration of trading in a few EU countries; the relocation of

domestic trading for many European countries; and the increased specialisation of venues. Confirming

the transfer of volumes in a few countries, share trading remains highly concentrated on a few trading

venues after the UK’s withdrawal.

1

This article was written by Lorenzo Danieli and Caroline Le Moign (ESMA). The article also benefited from discussions and

analyses held at the Committee for Economic and Markets Analysis MiFID Task Force, as well as from precisions from

colleagues from the Markets and Digital Innovation Department.

ESMA TRV Risk Analysis 30 October 2023 4

Introduction

Since the launch of the EU capital markets union

(CMU) initiative in 2015, new legislative and non-

legislative proposals have been made to create a

single market for capital

2

, including reviews of the

main legislation of capital markets: the markets in

financial instruments directive (MiFID II) and the

markets in financial instruments regulation

(MiFIR)

3

. The MiFID II / MiFIR package started

applying in January 2018.

In 2020, the European Commission’s

assessment on CMU stated that ‘while progress

has been made […], EU capital markets remain

fragmented [meaning] that European citizens and

businesses are not able to fully benefit from the

sources of funding and investment that capital

markets can offer.’ Thus, an action plan was

adopted in 2020 with a focus on integrating

national capital markets into a genuine single

market, followed up in 2022 with new legislative

proposals aiming at streamlining the listing

process on EU stock exchanges and clearing

services.

In parallel, several events have affected

European equity markets in the last years, such

as the COVID-19-related market stress, and the

withdrawal of the UK from the EU. Furthermore,

equity markets also saw the increase in retail

trading activity

4

, mergers among important

exchanges

5

and the evolution of their business

models. If trading venues (TVs) continue to

compete for listings and order flow, through fee

structure or competing services (e.g. clearing and

settlement, different trading protocols), their

revenues from trade-data-related services have

become more important (Duffie et al., 2022). In

an upcoming ESMA working paper, we will test

the significance of these main changes through a

panel regression model, to test the descriptive

statistics described in this article.

The aim of our analysis is to present the evolution

of the European market structure making use of

2

See CMU-dedicated web pages on the Commission

website, presenting action plans, legislative proposals,

packages already put in place and progress reports.

3

Directive 2014/65/EU on markets in financial

instruments and amending Directive 2002/92/EC and

Directive 2011/61/EU (recast); and Regulation (EU) No

600/2014 on markets in financial instruments and

amending Regulation (EU) No 648/2012.

4

Retail traders appear to participate more in European

stock markets, both in all-to-all trading mechanisms

where they interact with all types of traders, or in venues

operating retail-specific mechanisms (Aramian and

Comerton-Forde, 2023). See ESMA (2022), Key Retail

Risk Indicators for the EU Single Market. Reflecting the

importance of retail risk monitoring, since 2020, ESMA

regulatory data, with a specific focus on share

trading since 2019

6

. In the MiFIR review

7

that has

been agreed in July 2023, one of three priorities

for the review is to ‘improv[e] the level-playing

field between execution venues’. Thus,

identifying and understanding the evolution of the

European market structure during the recent

transformative years is key to assess this

objective, and the new level of trading

concentration. On the one hand competition

among venues can lead to more innovative

services and lower fees, on the other a

fragmented trading landscape may also impact

market liquidity. This article contributes to

ESMA’s work to promote effective and stable

financial markets.

Share trading competition

in the economic literature

The literature on trading venue competition

highlights a trade-off between the positive effects

that arise from increased competition, such as

reduced spreads and increased price efficiency

(O’Hara and Ye, 2011), and negative network

externalities that arise when liquidity is dispersed

among venues.

A consolidated market leads to better execution

as more traders are present, leading to higher

liquidity (Pagano, 1989). However, where traders

are heterogeneous with respect to their beliefs

and motives, different market structures can

better serve their needs (Harris and Raviv, 1993).

Increasing electronification has brought these

views together, highlighting the crucial role of

transparency: the market is virtually

unfragmented to traders with informational

access to all venues (Gresse, 2017). But fast-

trading technology has also intensified

competition for order flow between TVs, with the

possible consequence of additional costs

stemming from the speed race to react to

information. Thus, while competition reduces

has an additional specific mandate to develop ‘retail risk

indicators for the timely identification of potential causes

of consumer and investor harm’ (Article 9(1ab) of the

revised ESMA regulation).

5

For instance, Euronext acquired Borsa Italiana in 2021

and the London Stock Exchange acquired the data

vendor Refinitiv.

6

This article is a companion analysis to the Market

Report on EU Securities Markets, which provides an

overview of all equity and bond markets.

7

See Proposal for a Regulation of the European

Parliament and of the Council amending Regulation

(EU) No 600/2014.

ESMA TRV Risk Analysis 30 October 2023 5

trading costs, an increase in the number of TVs

may also lead to more arbitrage opportunities and

heightened adverse selection for liquidity

providers, which respond to increased spreads

(Baldauf and Mollner, 2021).

Another important feature of market

fragmentation is that its benefits are not linear

depending on the characteristics of the stocks, for

example a moderate degree of fragmentation can

be liquidity maximising for large capitalisation

stocks (Degryse et al., 2015), but detrimental for

small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and

other less-actively traded stocks (Lausen et al.,

2021).

Analysing the mergers, the economic literature

points towards overall positive effects on stock

liquidity, which are, however, concentrated on

stocks with large market capitalisation or foreign

exposure (Nielsson, 2009, on the Euronext

mergers during the 2000s). In terms of overall

market structure, exchange mergers do not lead

to significant increase in industry concentration in

the long term (Otchere and Abukari, 2020,

analysing six trading venue mergers in the EU

and the US).

Evolution of EEA share

market structure

Using transparency data reported from 2019 to

2022, this section analyses the evolution of the

European Economic Area (EEA) equity market

structure following the implementation of MiFID

II

8

. This dataset includes reference data from the

Financial Instruments Reference Database

System (FIRDS), and additional reference and

trading activity information from the Financial

Instruments Transparency System (FITRS)

9

.

8

The perimeter includes all EEA countries since MiFID

II / MiFIR are texts with EEA relevance. For further

information on European markets, including on all

equity and bond instruments, see ESMA (2021), EU

Securities Markets – ESMA annual statistical report.

9

See ESMA (2020), EU Securities Markets – ESMA

annual statistical report for a presentation of the data

collection and treatment. See also the ESMA website to

access the data registers.

10

The UK, which remained part of the EU single market

as part of the transition period stipulated in the EU–UK

Withdrawal Agreement, continued to submit data to the

MiFID II reporting system throughout 2020. In all the

charts, the perimeter is always described: when ‘EEA’

is mentioned, the perimeter is the current EEA

perimeter of 30 countries; when ‘EEA + UK’ is

presented, the perimeter is EEA pre-withdrawal of the

UK, meaning the EEA with 31 countries, including the

UK.

11

RMs are multilateral systems operated by a market

These figures are also compared to the US

microstructure using public and commercial data

on share trading in the US. In order to show the

impact of the UK’s withdrawal from the EU, our

analysis presents the evolution of the EEA

including UK numbers until the end of the

transition period at the end of 2020, and without

afterwards

10

. This article focuses on the

microstructure of share trading in the EEA and

does not integrate volumes traded for other

equity instruments such as exchange-traded

funds.

In the EEA and according to MiFID II / MiFIR,

shares can be traded on exchange or off

exchange. On-exchange trades can be carried

out on TVs, through a regulated market (RM) or

a multilateral trading facility (MTF). Off-exchange

trades can be carried out through a systematic

internaliser (SI) or over the counter (OTC)

11

.

The share trading obligation (STO) was

introduced in the MiFIR framework

12

in order to

increase market transparency by shifting OTC

share trading onto lit trading platforms.

Investment firms that undertake trading in shares

have to ensure that trading takes place on a RM,

MTF or SI, or a third-country TV assessed as

equivalent, except for infrequent or exceptional

trades that do not contribute to the price

discovery process.

The UK had a pivotal role in European

securities trading, and its withdrawal from the

EU brought a significant drop in overall trading in

2021. Trading volumes on UK TVs in 2019 and

2020 accounted respectively for 50 % and 69 %

of share volumes traded on exchange in the

EEA + UK. Since all EEA shares are within the

scope of the STO

13

, this meant that all EEA

shares had to be traded on EEA or equivalent

third-country venues. Thus, the end of the

transition period and the STO translated into an

operator, which bring together multiple third parties

buying and selling interests in financial instruments, in

accordance with its non-discretionary rules, and in a

way that results in a contract. MTFs are another type of

non-discretionary venue, very similar to RM, but they

can be operated by an investment firm or a market

operator. SIs are investment firms that, on an

organised, frequent, systematic and substantial basis,

deal on own account when executing client orders,

proposing a bilateral discretionary system. They offer

an avenue for trading outside a lit market, but without

the liquidity disadvantage of pure bilateral OTC

transactions.

12

Article 23 of Regulation (EU) No 600/2014.

13

ESMA clarified that in the context of Brexit, the STO

applies to all EEA shares, aside from EU investment

firms trading EEA shares on UK TVs in pound sterling –

fewer than 50 shares.

ESMA TRV Risk Analysis 30 October 2023 6

important drop in share trading in 2021, from

EUR 25.0tn in the EEA + UK to EUR 13.5tn in the

EEA (– 46 %), since many EEA shares were

mainly traded in the UK (see following sections).

In comparison, UK shares were only seldom

traded on EEA TVs, with 11% of UK share

volumes traded on EEA TVs on average in

2019/20.

This important decrease in volumes was

accompanied by four main changes of the EEA

market structure: a decrease in the number of

infrastructures trading shares, even though they

remain elevated; a new distribution of trading,

both by market type and by country; the

relocation of domestic trading; and the increased

specialisation of venues. However, the

concentration of trading on a few venues remains

elevated.

High number of EEA groups and

infrastructures, even after 2021

For TVs, the market structure in Europe

encompasses three layers of consolidation.

Exchange groups represent the highest level of

consolidation among stock exchanges (Chart 1).

They are the parent company of a set of operating

entities (from one or multiple countries) that work

with the same set of group-specific rules, single

disclosure and governance regimes, and single

tax treatment (Wright and Hamre, 2021). All

those entities are identified through international

indicators called market identifier codes (MICs)

14

.

Exchange groups are composed of market

operators that may run one or more TVs (market

segments). Operating entity MICs identify market

operators, and market segment MICs classify a

section of the market operator, usually a

specialisation in one or more specific instruments

(equity, bonds, derivatives, SME shares, etc.)

15

.

There are also cases in which a market operator

does not have a parent company and is therefore

considered as non-consolidated. Off-exchange

SIs do not have the same structure: as

investment firms, they are not part of an

exchange group but frequently operated by large

banks. By combining the information on TVs

14

For the definitions presented in the paragraph, see

International Organization for Standardization 10383

frequently asked questions, November 2020.

15

For example, the operating MIC for the Athens

Exchange Group is ‘ASEX’. Under ASEX, there are five

associated market segment MICs: ENAX (alternative

market, where investors can trade in stocks), HOTC

(OTC market), XADE (RM, where instruments available

for trading are futures, options and repos), XATH (RM,

where investors can trade – among other things – in

stocks, exchange-traded funds and bonds), XIPO

publicly available on the ESMA registers with

publicly available information on their parent

companies, it is possible to trace the ownership

structure of consolidated groups

16

.

The number of consolidated groups remains

elevated at the end of 2022, even though some

mergers have occurred since the application of

MiFID II (Chart 2). The number of groups with

EEA operators trading shares slightly declined

from 40 groups in 2019 to 37 in 2021 and 2022 –

out of which 26 groups are domiciled in the EEA,

four in the UK and seven outside the EEA (mostly

in Japan, Switzerland and the US). Among these

groups, few have only one single TV trading

share (nine in 2019 and 2020, and eight in 2021

and 2022), and the largest group included seven

market operators and 34 TVs trading shares in

2022.

On-exchange volumes from groups domiciled in

the EEA have increased from 30 % in 2019/2020

to 39 % in 2021/2022, with a comparable

decrease of volumes from groups in the UK (– 8

percentage points (ppt) from the 2019/2020

simple average to the 2021/2022 simple average)

and outside of the EEA (– 1 ppt). UK-domiciled

groups concentrate the largest share of dark

trading on exchange (57 % of trading under pre-

(specialised in initial public offerings).

16

Each TV has a legal entity identifier that enables unique

identification of legal entities participating in financial

transactions, which can be matched with ‘level 2’ data

available on the Global Legal Entity Identifier

Foundation (GLEIF) website. These data include

information on legal entities that report their ‘direct

accounting consolidated parent’ together with their

‘ultimate accounting consolidated parent’. See GLEIF

‘Level 2 data: Who owns whom’.

Chart 1

Example of on-exchange equity market structure

Consolidating

group

Country 1

Country 2

Country 3

Market

operator 1

Market

operator 2

Market

operator 3

TVa

TVb

TVc

Exchange

group

Operating

entity

Market

segment

Country 1

Market

operator 4

Non-

consolidating

TVd

TVe

TVf

TVg

TVh

TVi

TVj

ESMA TRV Risk Analysis 30 October 2023 7

trade waivers and 97 % of trading under post-

trade deferrals in 2021/2022 – see the following

subsections for definitions).

The European share trading landscape is

characterised by a high number of

infrastructures split among RMs, MTFs and SIs

(Chart 3). By the end of 2020, there were 181 TVs

(59 RMs, 122 MTFs) and 63 SIs trading shares in

the EEA + UK

17

. Among them, a large number

were domiciled in the UK (30 MTFs, two RMs and

19 SIs).

After the withdrawal of the UK from the EU, the

number of active EEA infrastructures decreased

only slightly. At the end of 2020 there were

respectively 57 RMs, 92 MTFs and 44 SIs in the

EEA. In terms of new authorisations, two new

RMs, nine new MTFs and 21 new SIs were

authorised in the EEA in 2021 and 2022, with

some of those infrastructures not or not yet

trading shares. Hence, the number of active

infrastructures stood at 158 TVs (59 RMs, 99

MTFs) and 47 SIs at the end of 2022.

17

In this article we report the number of TVs and SIs

(identified with segment MICs) on which share trading

occurred at least once during the reporting year.

18

See the US Securities and Exchange Commission

website. The four groups are Cboe Global Markets,

Intercontinental Exchange, Nasdaq and Miami

International Holdings. The four remaining exchanges

are independent, with most of them recently created,

with the explicit aim to improve transparency and

competition for smaller investors (e.g. IEX or Members

Exchange).

19

The US microstructure was always much more

The European share trading landscape appears

to be significantly more fragmented if

compared to the US markets, where only 24

national stock exchanges were active at the end

of 2022 – out of which 20 belong to only four

groups

18

. Different historical evolution and

regulatory choices help to explain the current

market structures, such as the introduction since

2005 in the US of a central data consolidation

system for pre- and post-trade transparency

information and a dynamic best execution rule

19

.

This difference is also a reflection of the

European jurisdictions that have each grown

national markets, as wells as the many types of

infrastructures in the EU regulation that can

propose specific trading characteristics (see for

instance the differences between RMs and MTFs

in the sub-section Increase in trading

specialisation of venues).

Despite the larger number of infrastructures,

trading activity in the EEA remains

comparatively low in comparison to the US.

Trading volumes in shares in the US amounted to

EUR 86.3tn in 2022, compared to EUR 13.4tn in

concentrated: in 2000, the New York Stock Exchange

and NASDAQ accounted for 95 % of US on-exchange

trading volumes. The Regulation National Market

System implemented in 2005 increased competition

between venues: by mandating connectivity between

the markets, it removed the barriers to entry and

increased competition (Haslag and Ringgenberg,

2022). By 2016, NYSE and NASDAQ accounted for

less than 30 % of US volumes. The American market

capitalisation is also more important than the European

one.

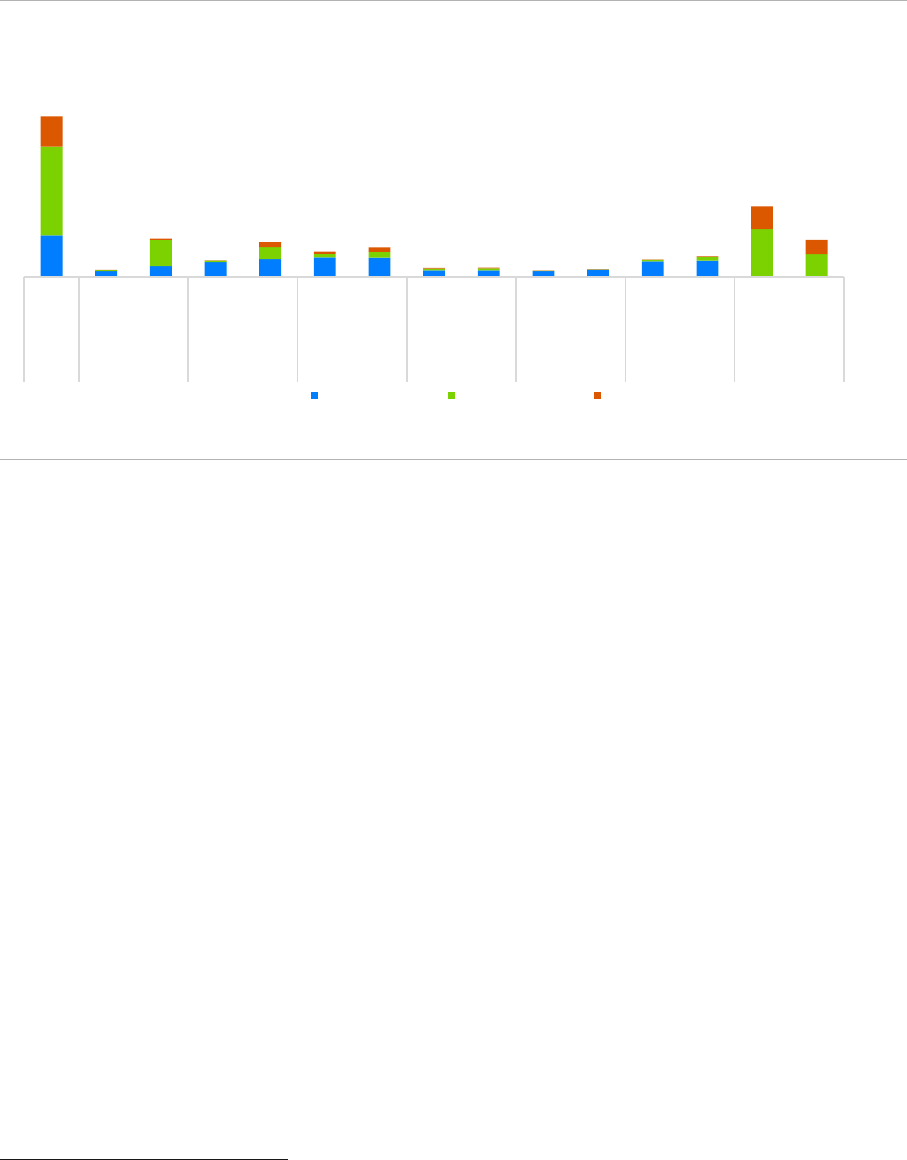

Chart 2

Number of groups trading shares, by domicile

High number, slight decrease since 2019

Chart 3

Number of venues and SIs trading shares

High number of infrastructures, also after

Brexit

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

2019 2020 2021 2022

EEA UK non EEA

Note: Number of unique groups with venues trading shares in the EEA, by

country domicile.

Sources:FITRS, GLEIF, ESMA.

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

200

EEA UK EEA UK EEA EEA

2019 2020 2021 2022

RM MTF SI

Note: Number of unique venues and SIs trading shares in the EEA and UK,

by type.

Sources: FITRS, ESMA.

ESMA TRV Risk Analysis 30 October 2023 8

the EEA (6.4 times less). Even before the UK’s

withdrawal, US share trading volumes were close

to three times higher than in the EEA + UK

(EUR 71.7tn compared to EUR 25tn).

Changing trading landscape after

2020

While turnover volumes were equally distributed

across market types in 2019 and 2020, the

trading landscape shows a significantly higher

share of on-exchange trading (from 53 % and

55 % in 2019 and 2020 to more than 70 % both

in 2021 and 2022). The largest change was

observed off-exchange, with the share of SI

activity more than halving since 2021 (7 % and

6 % of share turnover volumes in 2022), as the

majority of SIs that were authorised in the

EEA + UK were domiciled in the UK. OTC trading

slightly declined by 4 ppt to 22 % of total shares’

volumes in 2021 and 2022 (v 27 % in 2019 and

26 % 2020).

On-exchange volumes were almost equally

distributed between RMs and MTFs prior to the

UK’s withdrawal (29 % of overall shares’ volumes

on RMs and 27 % on MTFs in 2020), while there

has been a greater amount of activity on RMs

since then. RMs have increased their market

share, with 40 % of total share trading in the EEA

in 2021/2022, while MTFs have increased theirs

only slightly, to 32 % in 2021/2022.

The changing composition of the structure of on-

exchange trading is explained by the fact that

MTF trading was highly concentrated in the UK,

with 30 UK MTFs in 2020 out of a total of 122

MTFs in the EEA + UK, concentrating an average

of 93 % of the trading volumes on MTFs in

2019/2020 (Chart 5).

Since the UK’s withdrawal, the concentration of

MTF trading remained concentrated within three

countries, making up 95 % of MTF trading in

2022: the Netherlands (57 %), France (29 %) and

Germany (9 %). This is linked to the migration of

some of the volumes traded on UK MTFs to the

Netherlands’ MTFs (volumes multiplied by 633,

from EUR 3.5bn on average in 2019/2020 to

EUR 2.2tn on average in 2021/2022) and to

France’s MTFs (volumes multiplied by 121, from

EUR 11.6bn to EUR 1.4tn).

Turnover volumes on RMs remained more evenly

distributed among EEA countries (Chart 5). If the

two UK RMs were gathering 21 % of share

trading on EEA + UK RMs in 2019/2020,

Germany (21 % on average in 2019/2020) or

France (17 %) also had significant shares of RM

trading. After the UK’s withdrawal, domestic

trading on RMs increased in general. Germany

and France continued to have the highest share

of RM volumes on average in 2021/2022 (24 %

and 20 % respectively), followed by the

Netherlands (12 %) and Italy (11 %).

Relocation of domestic trading

The evolution of share market microstructure

after Brexit is also characterised by a change in

trading patterns related to the domicile of the

traded shares. In this article, we characterise

shares by issuer domicile, with ‘domestic share’

meaning that the domicile of the share is the

same as the domicile of the TV or SI it is traded

on; ‘other EEA share’ or EEA ‘cross-border

trading’ when the share domicile is different from

Chart 4

Annual turnover volumes by market type

On-exchange trading increased after Brexit

Chart 5

Annual trading volume by venue domicile

UK dominated MTF turnover pre-Brexit

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

On exchange SI OTC

2019 2020 2021 2022

Note: Share of annual turnover volumes in shares by market type, in %. In

2019 and 2020 the perimeter is the EEA + UK, in 2021 and 2022 the EEA.

Sources: FIRDS, FITRS, ESMA.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

MTF RM MTF RM MTF RM MTF RM

2019 2020 2021 2022

DE FR NL IT SE UK Other

Note: Annual trading volumes in shares by market type and trading venue

domicile. Share of the total, in %.

Sources: FIRDS, FITRS, ESMA.

ESMA TRV Risk Analysis 30 October 2023 9

the domicile of the TV or SI, but from another EEA

country; and ‘non-EEA share’ when the share has

an issuer from outside the EEA

20

.

Overall, a decrease of trading of non-EEA

shares is observed after the UK’s withdrawal,

since most of those transactions took place in the

UK. Turnover of non-EEA shares decreased by

– 54 % after Brexit, from EUR 4.1tn in 2019/2020

to EUR 1.9tn in 2021/2022. This decrease is

particularly large on venues and SIs, with a

– 64 % decrease (from EUR 2.4tn to EUR 869bn)

(Chart 6). In 2019/2020, 90 % of those volumes

on venues and SIs were traded on UK TVs or SIs

(EUR 2.2tn), with other volumes in Germany

(EUR 161bn, 7 %).

In 2021/2022, non-EEA shares were mostly

traded on French (41 %) and German (37 %) TVs

and SIs. This translated into large surges of non-

EEA volumes in France, with non-EEA turnover

growing from EUR 6.5bn to EUR 361.2bn in

France, and from EUR 161bn to EUR 322.8bn in

Germany on average from 2019/2020 to

2021/2022 (multiplied by 55 and doubled

respectively). Non-EEA shares were also traded

OTC, with an increase of this trading type after

2021 (from 40 % of overall non-EEA volumes in

2019/2020 to 54 % in 2021/2022).

Similarly, intra EEA cross-border trading

decreased and migrated towards a few

countries. Before the UK’s withdrawal, 90 % of

20

The regulatory dataset does not allow the domicile of

transactions happening OTC to be characterised, thus

it is not possible to compare the domicile of the share

intra-EEA cross-border trading volumes were

observed on UK TVs and SIs, with EUR 7.2tn on

average in 2019/2020. Cross-border share

trading on TVs and SIs halved to EUR 3.7tn on

average in 2021/2022. The volumes are mainly

concentrated in the Netherlands (52 %), France

(24 %) and Germany (12 %). This new

specialisation in trading shares from other

Member States was accompanied by an increase

in EEA cross-border volumes in the Netherlands

and France (respectively multiplied by 25 and

6.5).

Another transformation is the relocation of

domestic shares trading. Before the UK’s

withdrawal, only 41 % of the volumes of the

shares issued in an EEA country were traded on

the TVs or SIs of the same country (Chart 7). For

instance, 30 % of Dutch shares volumes on

venues and SIs were traded in the Netherlands in

2019/2020, and similarly 38 % of French shares

volumes on venues and SIs were traded in

France. This means that on average in the EEA,

59 % of the domestic shares trading was

occurring in other EEA countries’ TVs and SIs in

2019/2020, with the vast majority of those

volumes in the UK (see previous chart).

issuer and the domicile of the OTC transactions. Only

venues and SIs domicile is taken into account.

Chart 6

Shares volumes by issuer and venue domicile

Decrease in non-EEA shares volumes, concentration of EEA cross-border trading

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

2021—2022

2019—2020

2021—2022

2019—2020

2021—2022

2019—2020

2021—2022

2019—2020

2021—2022

2019—2020

2021—2022

2019—2020

2021—2022

2019—2020

2019—2020

OTCOtherSEITDEFRNLUK

Domestic Other EEA Non-EEA

Note: Average share turnover on venues and SIs, EUR trillion, in shares with an issuer from the same country (domestic), from another EEA country (other EEA) or

outside the EEA (non-EEA), for 2019/2022 and 2021/22.

Sources: FIRDS, FITRS, ESMA.

ESMA TRV Risk Analysis 30 October 2023 10

This situation, observed on average, was not

similar in all EEA countries, with some smaller

Member States observing more than 95 % of

their domestic shares traded on their domestic

TVs and SIs in 2019/2020 (e.g. Estonia, Latvia,

Lithuania, Slovenia or Slovakia). From 2021, a

relocation of domestic share trading is observed

on average, with 61 % of volumes on TVs and SIs

traded in the same country as the issuer of the

shares. This relocation is particularly noticeable

for the Netherlands (+ 32 ppt between the

2019/2020 and 2021/2022 average), France

(+ 27 ppt), Ireland (+ 20 ppt) and Germany

(+ 18 ppt).

Increase in trading specialisation of

venues

Venues tend to specialise by proposing different

trading characteristics, with some that are

observable in the transparency data, such as

trading certain domestic shares or shares from

small or large companies. Introduced by MiFID I,

MTFs adopted a similar microstructure as RMs,

characterised by a visible order book and the

presence of central clearing counterparties, with

some proposing more diverse trading protocols.

Several MTFs operate as dark book only. Since

their creation, those trading platforms are also

competing on fees and technology, as well as on

the number of instruments available for trading by

21

Based on Article 4 of MiFID II, SMEs are defined in this

article as the listed companies the market capitalisation

offering a wide range of EEA and non-EEA

securities (Fioravanti and Gentile, 2011).

On average, the number of shares available for

trading on MTFs is 10 times higher than on RMs

in 2019 and 2020 (around 1 600 v 160), and 11

times in 2021 and 2022 (around 1 500 v 140)

(Chart 8). Nevertheless, only half of these shares

available were actually traded on MTFs (55 % in

2019 and 2020, 62 % in 2021 and 2022),

whereas 83 % of the shares available for trading

on RMs were traded on RMs in 2021 and 2022

(80 % in 2019/2020).

The second main trading characteristic of MTFs

is their specialisation in foreign trading,

meaning a major part of their volumes comes

from trading shares issued in an EEA country

different from the MTF domicile and non-EEA

shares. In this respect, domestic trading

accounted for only 21 % of MTF share trading in

2019/2020 and 18 % in 2021/2022 (Chart 9),

while trading of shares from other EEA Member

States amounted to 65 % (vs. 68 % in

2019/2020) and non-EEA share trading to 14 %

(vs. 11 % in 2019/2020).

MTFs are the main venue for trading in SMEs

shares

21

, especially since the introduction of the

possibility for SMEs to be listed on growth

markets in MiFID II / MiFIR as part of the CMU

agenda, which provides for a lighter reporting

of which is below EUR 200 million.

Chart 7

Share of domestic shares trading by country

Domestic trading of shares increased

Chart 8

Average number of instruments available to trade

Far higher number of shares available on

MTFs

0% 20% 40% 60% 80%

IE

ES

SE

IT

DE

FR

NL

EEA

EEA + UK

2019—2020 2021—2022

Note: Domestic share trading on domestic infrastructures, in % of total

domestic share trading on all venues and SIs, for 2019/2020 and 2021/2022.

Lecture: In 2019/2020, 18% of trading volumes in Irish shares were traded

on Irish venues or SIs. In 2021/2022, 38% of the Irish share volumes on all

venues and SIs were traded on Irish venues or SIs.

Sources: FIRDS, FITRS, ESMA.

0

0.1

0.2

0.3

0.4

0.5

0.6

0.7

0.8

0.9

-

200

400

600

800

1,000

1,200

1,400

1,600

1,800

MTF RM MTF RM MTF RM MTF RM

2019 2020 2021 2022

Listed % traded

Note: Average number of shares available for trading (lhs) and share of

traded stocks by market type (rhs).

Sources: FIRDS, FITRS, ESMA.

ESMA TRV Risk Analysis 30 October 2023 11

burden and reduced compliance costs for SME

listing

22

.

Overall, SME trading volumes were higher on

MTFs than on RMs. Although this difference was

small before the UK’s withdrawal (SME trading

volumes amounted to 1.5 % and 1.3 % of MTFs

and RMs volumes respectively in the EEA + UK

on average in 2019/2020), the activity in SME

shares on MTFs increased afterwards. SME

volumes represented 2.2 % of MTF shares’

volumes on average in 2021/2022, while this

share went down on RMs to 0.7 % of RM shares’

volumes in 2021/2022.

The UK dominated SME trading in 2019 and

2020 with respectively 35 % and 39 % of the total

trading in SMEs. SME volumes continued to be

concentrated after the UK’s withdrawal, mainly in

French and German venues and SIs (20 % and

16 % of SME volumes on average, respectively,

in 2021/2022), with also an increase in OTC

22

Market operators can apply for their MTF to be

registered as an SME growth market, provided that

50 % of the issuers with shares available for trading on

their MTF are SMEs.

23

See ESMA (2022), Annual Report 2022 Waivers and

Deferrals, for more detailed information on pre- and

post-trade deferrals and their implementation, along

with statistics of volumes and transactions under each

waiver and deferral. Article 4 of MiFIR sets out four

different type of pre-trade transparency waivers for

equity instruments: the reference price; negotiated

trade; large-in-scale and order management facilities

waivers. In terms of numbers of waivers, large-in-scale

waivers are the main type.

trading (from an average of 15 % in 2019/2020 to

41 % in 2021/2022).

MTFs are also specialised in dark trading.

Under the MiFID II / MiFIR framework, market

operators and investment firms are required to

publicly provide both the current bid and offer

prices and the depth of trading interests at those

prices (pre-trade transparency), along with the

price, volume and time of the executed

transactions (post-trade transparency), both as

close to real time as is technically possible.

‘Dark trading’ is defined as trading under pre-

trade waivers, meaning when the pre-trade

transparency requirements are waived by

national competent authorities. For equity

instruments, MiFID II / MiFIR allow the pre-trade

transparency obligations to be waived (in

particular for transactions that are large in scale

compared to the normal market size, for using the

available reference price or for systems that

formalise negotiated transactions) and allow

post-trade transparency publication to be

deferred, mainly for large-scale transactions

23

.

Trading under waivers and deferrals has

decreased since the UK’s withdrawal, especially

trading under pre-trade waivers (dark trading).

The decrease in trading under post-trade

deferrals went down in the same levels as the

overall trading volumes, from EUR 4.4tn on

average in 2019/2020 to EUR 2.6tn in 2021/2022

(– 43 %), whereas trading under pre-trade

waivers decreased by – 55 %, from EUR 4.0tn in

2019/2020 to EUR 1.8tn in 2021/2022

24

.

This type of trading is also increasingly

concentrated on MTFs after 2021: 92 % of all

volumes in shares traded under pre-trade

waivers and 40 % under post-trade deferrals in

2021/2022 occurred on MTFs (v respectively

90 % and 34 % in 2019/2020 for pre- and post-

trade waivers and deferrals volumes). The rest of

trading under pre-trade waivers happens on RMs

(8 % of volumes under pre-trade waivers in

2021/2022), while deferred volumes are also

24

Turnover statistics for pre trade waivers and deferrals

are only presented for MTFs and RMs. In general, there

are no waivers for OTC-trading given that OTC-trading

is not subject to pre-trade transparency. There are

exceptions for SIs, where the concept of standard

market size (SMS) applies for determining the quoting

obligations. MiFID II requires that SIs publish bid and

offer prices for a size at least equal to 10 % of the SMS

for liquid shares and equivalent liquid instruments (such

as ETFs and certificates). However, SIs are free to

propose to their clients, in addition to their public

quotes, bilateral quotes that are not subject to pre-trade

transparency when they are higher than the SMS.

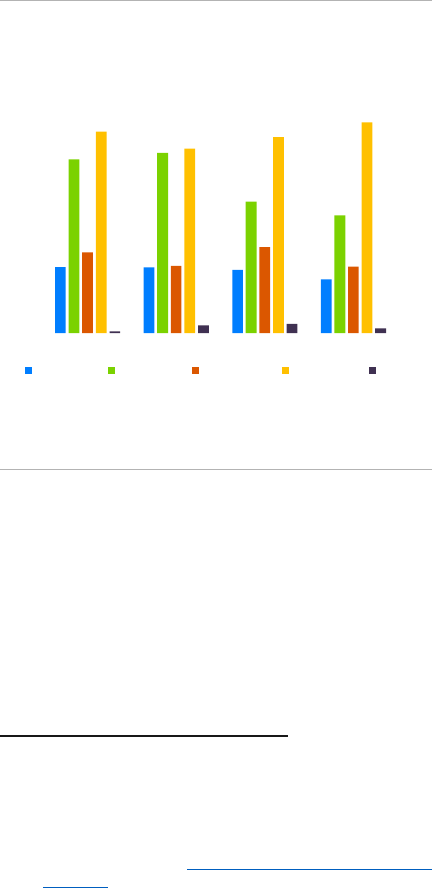

Chart 9

MTF share trading by characteristics

MTFs specialised in foreign, SME, dark

trading

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

2019 2020 2021 2022

Domestic Pre-trade Post-trade Large cap SME

Note: Annual turnover in shares on multilateral trading facilities. Domestic =

turnover in 'domestic' shares. Large cap = turnover in shares with a market

capitalisation larger than EUR 20bn. SME = turnover in shares with a market

capitalisation smaller than EUR 200mn. Pre-trade = turnover under pre-trade

waiver. Post-trade = turnover under post-trade deferral.

Sources: FIRDS, FITRS, ESMA.

ESMA TRV Risk Analysis 30 October 2023 12

observed OTC (55 % of volumes under post-

trade waivers) and on SIs (4 % in 2021/2022).

Trading under waivers or deferrals therefore

represents the majority of MTF volumes: 39 % of

MTFs volumes in shares came from volumes

under pre-trade waivers and 24 % from volumes

under post-trade deferrals in 2021/2022

(respectively 56 % and 23 % in 2019/2020). In

comparison, on RMs, trading under pre-trade

waivers represented only 2 % of share volumes

in 2021/2022 (3 % in 2019/2020) and 0.3 % for

volumes under post-trade deferrals (1 % in

2019/2020).

Finally, and contrary to MTFs, RMs specialise in

trading quasi-exclusively domestic shares (i.e.

shares from an issuer of the same country as the

venue). This characteristic remained stable over

time, with 90 % of domestic trading on average in

2019/2020 and 88 % in 2021/2022. This is linked

to RMs being most often the primary market

where companies issue their stock.

By instrument size, the majority of turnover

volumes on MTFs and RMs is in shares from

very large capitalisation companies (with a

market capitalisation above EUR 20bn). It

accounted for more than half of total trading

volumes on each market type in 2019/2020 (55

% on average on RMs and 61 % on MTFs). After

the UK’s withdrawal, RMs increased their

specialisation in trading very large cap. shares,

which represented 62 % of the volumes traded on

RMs in 2021/2022 (64 % on MTFs in 2021/2022).

Overall, RMs increased their share in total large-

cap. volumes in the EEA, reaching 39 % in

2021/2022 (25 % on average in 2019/2020),

when MTFs share went from 27 % to 31 %.

High level of on-exchange trading

concentration remains

Share-trading activity on exchange is mostly

concentrated on few large TVs. The first 10 TVs

in shares turnover volumes have gathered almost

three quarters of on-exchange volumes in shares

since 2019. Even after 2021, the top 10 recorded

74 % of all on-exchange turnover in 2021 and

2022, with five new venues joining this ranking.

Concentration is particularly high for the top 10

RMs, which concentrated 95 % of RM volumes in

2019 and 2020 (93 % in 2021 and 2022). The 10

largest MTFs in terms of turnover volumes were

all from the UK in 2019 and 2020, and

concentrated respectively 88 % and 85 % of

MTFs volumes. After 2021, the first 10 MTFs

were domiciled in four different countries but

were even more concentrated (89 % of MTF

volumes in 2021 and 90 % in 2022).

The trading concentration in the US, even with

a smaller number of venues, appears higher. The

first five venues accounted for 74 % of US on-

exchange share turnover in 2022, a

concentration that has remained stable in the last

years (76 % on average since 2019). Considering

a similar perimeter, the first five venues trading

shares concentrated 67 % of the EEA + UK

volumes on average in 2019/2020, with the

Chart 10

RM share trading by characteristics

RMs specialised in domestic, large-cap.

trading

Chart 11

Share trading concentration by market type

Very high trading concentration, especially

on RMs

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

2019 2020 2021 2022

Domestic Pre-trade Post-trade Large cap SME

Note: Annual turnover in shares on regulated markets. Domestic = turnover in

'domestic' shares. Large cap = turnover in shares with a market capitalisation

larger than EUR 20bn. SME = turnover in shares with a market capitalisation

smaller than EUR 200mn. Pre-trade = turnover under pre-trade waiver. Post-

trade = turnover under post-trade deferral.

Sources: FIRDS, FITRS, ESMA.

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Top 10 venues Top 10 RM Top 10 MTF

2019 2020 2021 2022

Note: Share of on-exchange share trading on first 10 venues, RM and MTF by

turnover volumes, in % of each market type by turnover volumes.

Lecture: In 2022, the first 10 RMs concentrated 93% of share turnover

volumes traded on all EEA RMs.

Sources: FITRS, FIRDS, ESMA.

ESMA TRV Risk Analysis 30 October 2023 13

majority of them established in the UK

25

. After the

UK’s withdrawal, the concentration level declined

to 60 % on average in 2021/2022, with an

increased number of venue domiciles.

Conclusion

European market structure has changed in an

important manner since the implementation of

MiFID II / MiFIR. Making use of the regulatory

transparency data, this article analyses the

evolution of the EEA share market structure from

2019 to 2022.

Given its pivotal role in stock markets, the impact

of the UK’s withdrawal led to a major decrease in

trading volumes, and a decrease in the number

of infrastructures trading shares, even though

they remain elevated.

Since the beginning of 2021, a new distribution of

trading has been observed, both by market type

and by country, as well as the relocation of

domestic trading; and an increased specialisation

of venues. In an upcoming ESMA working paper,

we will test the significance of these main

changes through a panel regression model, to

test the descriptive statistics described in this

article. By identifying the evolution of trading

concentration and share trading competition

during the recent transformative years, this article

25

To allow for comparability with US figures that are

available at the operating entity levels, numbers are

presented here at the operating MIC level for the US

and the EEA, as opposed to the previous subsection

where the number of venues is presented at the

contributes to ESMA’s work to promote effective

and orderly financial markets.

segment MIC level. This is a natural choice given that

the Refinitiv Eikon market share reporter used for US

data provides figures at the operating MIC level.

Chart 12

Annual on-exchange turnover on EEA and US venues

Higher concentration of trading in the US

0% 20% 40% 60% 80% 100%

US

EEA + UK

US

EEA + UK

US

EEA

US

EEA

2019

2020

2021

2022

Top five venues Other

Note: Share of annual on-exchange turnover volumes in shares on the top

five US venues, compared to EEA + UK venues in 2019 and 2020 and EEA

venues in 2021 and 2022, in % of on-exchange trading volumes.

Sources: FIRDS, FITRS, Refinitv Eikon, ESMA.

ESMA TRV Risk Analysis 30 October 2023 14

Related reading

Anselmi, G., Nimalendran, M. and Petrella, G. (2022), ‘Order flow fragmentation and flight-to-

transparency during stressed market conditions: Evidence from COVID-19’, Finance Research

Letters, Vol. 44.

Aramian, F. and Comerton-Forde, C. (2023), ‘Retail trading in European equity markets’, Plato

Partnership.

Baldauf, M. and Mollner, J. (2021), ‘Trading in fragmented markets’, Journal of Financial and

Quantitative Analysis, Vol. 56, No 1, pp. 93–121.

Degryse, H., de Jong, F. and van Kervel, V. (2015), ‘The impact of dark trading and visible

fragmentation on market quality’, Review of Finance, Vol. 19, No 4, pp. 1587–1622.

Duffie, D., Foucault, T., Veldkamp, L. and Vives, X. (2022), Technology and Finance, Centre for

Economic Policy Research, Paris.

Fioravanti, S. F. and Gentile, M. (2011), ‘The impact of market fragmentation on European stock

exchanges’, CONSOB Working Paper, No 69.

Gresse, C. (2017), ‘Effects of lit and dark market fragmentation on liquidity’, Journal of Financial

Markets, Vol. 35, pp. 1–20.

Haslag, P. H. and Ringgenberg, M. C. (2022), ‘The demise of the NYSE and NASDAQ: Market quality

in the age of market fragmentation’, Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, pp. 1–30.

Lausen, J., Clapham, B., Gomber, P. and Bender, M. (2021), ‘Drivers and effects of stock market

fragmentation – Insights on SME stocks’, SAFE Working Paper, No 367.

Harris, M. and Raviv, A. (1993), ‘Differences of opinion make a horse race’, The Review of Financial

Studies, Vol. 6, No 3, pp. 473–506.

Nielsson, U. (2009), ‘Stock exchange merger and liquidity: The case of Euronext’, Journal of Financial

Markets, Vol. 12, No 2, pp. 229–267.

O’Hara, M. and Ye, M. (2011), ‘Is market fragmentation harming market quality?’, Journal of Financial

Economics, Vol. 100, No 3, pp. 459–474.

Otchere, I. K. and Abukari, K. (2020), ‘Are super stock exchange mergers motivated by efficiency or

market power gains?’, Journal of International Financial Markets, Institutions and Money, Vol. 64.

Pagano, M. (1989), ‘Trading volume and asset liquidity’, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 104,

No 2, pp. 255–274.

Wright, W. and Hamre, E. F. (2021), ‘The problem with European stock

marketshttps://newfinancial.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/2021.03-The-problem-

with-European-stock-markets-New-Financial.pdf’, New Financial.

ESMA TRV Risk Analysis 30 October 2023 15