What Are the Effects

of the ECB’s N

egative

Interest Rate Policy?

Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies

Directorate-General for Internal Policies

Author: Grégory CLAEYS

PE 662.922 - June 2021

EN

IN-DEPTH ANALYSIS

Requested by the ECON committee

Monetary Dialogue Papers, June 2021

Abstract

Several central banks, including the European Central Bank since

2014, have added negative policy rates to their toolboxes after

exhausting conventional easing measures. It is essential to

understand the effects on the economy of prolonged negative

rates. This paper explores the potential effects (and side effects)

of negative rates in theory and examines the evidence to

determine what these effects have been in practice in the euro

area.

This paper was provided by the Policy Department for Economic,

Scientific and Quality of Life Policies at the request of the

committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs (ECON) ahead of

the Monetary Dialogue with the ECB President on 21 June 2021.

What Are the Effects

of the ECB’s N

egative

Interest Rate Policy?

Monetary Dialogue Papers

June 2021

This document was requested by the European Parliament's committee on Economic and Monetary

Affairs (ECON).

AUTHOR

Grégory CLAEYS

1

, Bruegel

ADMINISTRATOR RESPONSIBLE

Drazen RAKIC

EDITORIAL ASSISTANT

Janetta CUJKOVA

LINGUISTIC VERSIONS

Original: EN

ABOUT THE EDITOR

Policy departments provide in-house and external expertise to support European Parliament

committees and other parliamentary bodies in shaping legislation and exercising democratic scrutiny

over EU internal policies.

To contact the Policy Department or to subscribe for email alert updates, please write to:

Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies

European Parliament

L-2929 - Luxembourg

Email: Poldep-Economy-[email protected]

Manuscript completed: June 2021

Date of publication: June 2021

© European Union, 2021

This document was prepared as part of a series on “Low for Longer: Effects of Prolonged Negative

Interest Rates”, available on the internet at:

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/committees/en/econ/econ-policies/monetary-dialogue

Follow the Monetary Expert Panel on Twitter: @EP_Monetary

DISCLAIMER AND COPYRIGHT

The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not

necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorised, provided the source is

acknowledged and the European Parliament is given prior notice and sent a copy.

For citation purposes, the publication should be referenced as: Claeys, G, What Are the Effects of the

ECB’s Negative Interest Rate Policy? Publication for the committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs,

Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies, European Parliament,

Luxembourg, 2021.

1

The author is grateful to Marta Dominguez Jimenez, Lionel Guetta-Jeanrenaud and Monika Grzegorczy for excellent research assistance

and to Rebecca Christie, Maria Demertzis, Francesco Papadia, Nicolas Véron and Guntram Wolff for their useful comments.

What Are the Effects of the ECB’s Negative Interest Rate Policy?

3 PE 662.922

CONTENTS

LIST OF BOXES 4

LIST OF FIGURES 4

LIST OF TABLES 4

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS 5

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6

INTRODUCTION 8

EFFECTS OF CENTRAL BANK NEGATIVE RATES IN THEORY 10

2.1. Potential positive effects on lending, output and ultimately inflation 10

2.2. Possible negative side effects for the financial sector 11

2.3. Possible reduced response of economic activity to interest rates 12

EFFECTS OF CENTRAL BANK NEGATIVE RATES IN PRACTICE 13

3.1. Transmission to market (interest and exchange) rates 13

3.2. Effects of negative rates on banks 15

3.2.1. Direct cost of a negative deposit facility rate for euro-area banks 15

3.2.2. Impact on other components of the balance sheets of commercial banks 18

3.3. Macro and financial stability impact 22

CONCLUSIONS: WHAT DO WE KNOW AND WHAT SHOULD THE ECB DO? 24

REFERENCES 27

IPOL | Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies

PE 662.922 4

LIST OF BOXES

Box 1: Estimating the pass-through of monetary policy to bank rates 20

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: Interest rates 9

Figure 2: Policy and market interest rate in the euro area 14

Figure 3: Euro nominal effective exchange rate 14

Figure 4: Excess liquidity held at the ECB and direct costs for the banks of the euro area 16

Figure 5: Direct cost of a negative deposit facility rate per country 17

Figure 6: Composite bank interest rates for households and corporations (%) 19

Figure 7: Bank lending to the private sector in the euro area (YoY, %) 22

Figure 8: Estimated impact of three ECB rate cuts (by 10 bps) on macro variables 23

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Relationship between monetary policy rate and banking rates 20

Table 2: Relationship between and banking rates in case of negative rates 21

What Are the Effects of the ECB’s Negative Interest Rate Policy?

5 PE 662.922

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ECB

European Central Bank

ELB

Effective lower bound

EU

European Union

GDP

Gross domestic product

NIRP

Negative interest rate policy

NFC

Non-financial corporations

PEPP

Pandemic emergency purchase programme

QE

Quantitative easing

TLTRO

Targeted longer-term refinancing operations

ZLB

Zero lower bound

IPOL | Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies

PE 662.922 6

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

• Since the global financial crisis, several central banks around the world have added negative

policy rates to their toolboxes after exhausting conventional easing measures.

• The European Central Bank introduced its negative interest rate policy (NIRP) in June 2014

when it decided to cut for the first time its deposit facility rate below 0%, to -0.1%. Since then, the

ECB has cut its deposit rate four more times, each time by 10 basis points, to reach -0.5% in

September 2019.

• NIRP has now been in place for seven years in the euro area and markets currently expect

rates to stay negative for at least five years. It is therefore crucial to fully understand the effects

on the economy of prolonged negative rates.

• Central banks which have adopted NIRP are generally positive about its use in helping them

fulfil their objectives. However, NIRP remains controversial and has been accused of causing

significant side effects in particular for the financial sector. Indeed, the existence of various

frictions (e.g. physical cash and possible cognitive biases) means that going below 0% could lead

to additional channels and non-linear effects of monetary policy.

• In this paper, we look at the potential (positive and negative) effects of negative rates and

describe the potential mechanisms at work when this measure is used, before turning to the

evidence.

• The experience of the euro area since 2014 shows that the negative deposit facility rate is

fully transmitted to the benchmark overnight rate and then propagates along the whole

yield curve.

• There is some evidence (in particular from Denmark and Switzerland) that NIRP also impacts

the exchange rate through a change in cross-border flows.

• As far as bank rates are concerned, it appears that the effects of rate cuts in negative territory

are not different to “standard” rate cuts. Like them, they reduce banks’ interest margins because

rates on banks’ assets are more sensitive to policy rates than rates on banks’ liabilities, but this effect

does not appear to be amplified below 0% (at least at the current minimal level of negative rates).

• A negative deposit facility rate implies some cost for banks that hold excess reserves at the

ECB. This cost has been growing significantly, in particular since the introduction of the pandemic

emergency purchase programme (PEPP) in 2020. Moreover, this cost is concentrated in the

countries that host the main European financial centres (where investors that have sold assets to

the ECB park their euro deposits).

• A more difficult and more fundamental question about negative rates is whether output,

employment and inflation are still sensitive to these financial variables when rates are very

low or negative. The ECB’s own research is confident that the effect of NIRP on these variables in

the short- to medium-term is positive. Potential negative side effects do not appear to have

materialised in a significant way for the moment.

• However, a long period of negative rates could also entail some medium- to long-term risk,

in particular in terms of financial stability. Financial institutions seem to have increased their risk-

taking with the advent of negative rates. Whether this risk-taking is excessive remains to be seen

and will need to be monitored carefully.

What Are the Effects of the ECB’s Negative Interest Rate Policy?

7 PE 662.922

• The direct cost incurred by banks that hold excess reserves appears to be the most tangible

side effect at this stage. The easiest solution to mitigate this would be to adjust the two-tier

system put in place in 2019 and to increase the quantity of excess reserves exempted from the

negative rate.

• If the ECB believes it is approaching the reversal rate but needs to provide more monetary

easing, it should refrain from cutting its deposit facility rate again, and instead cut further its

targeted longer-term refinancing operations rate.

• Negative rates for a too-long period could lead to financial instability. The best way to deal

with potential financial imbalances is to use macroprudential tools. However, the euro area’s

current macroprudential framework might not be capable of playing its role. It is therefore critical

to build a better set-up for the use of macroprudential tools, so that they can be used forcefully and

in a timely way when needed.

• Finally, given the current economic situation, the ECB should be extremely cautious and not

rush before exiting negative rates. Even if negative rates proved to be ineffective, it would be

extremely dangerous to exit negative rates too soon as it could harm the post-COVID-19 recovery

and destabilise European sovereign debt markets.

IPOL | Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies

PE 662.922 8

INTRODUCTION

Since the global financial crisis, and after exhausting conventional easing measures, several central

banks around the world have added negative policy rates to their toolboxes, in addition to other

unconventional measures such as asset purchases and forward guidance. The central bank of Sweden,

in July 2009, was the first to move one of its policy rates into negative territory. It was followed by the

central banks of Denmark (in July 2012), Switzerland (in January 2015), Japan (in February 2016) and by

the European Central Bank (ECB).

In the euro area, the ECB introduced its negative interest rate policy (NIRP) in June 2014 when the ECB

Governing Council decided to cut for the first time the ECB’s deposit facility rate (DFR) – the main policy

rate to influence market rates since the global financial crisis – below 0% to -0.1%. Since then, the ECB

has cut its deposit rate four more times, each time by 10 basis points (bps), to reach -0.5% in September

2019.

How did the ECB end up resorting to negative rates? While the ECB’s main refinancing operations rate

averaged around 3% between the creation of the ECB in 1999 and the failure of Lehman Brothers in

September 2008, it has averaged less than 0.5% in the 13 years since then. One obvious reason for this

is that the ECB has in that time faced the two most important economic crises in almost a century and

had to provide highly accommodative monetary policy to fulfil its price stability mandate. Another

more fundamental reason is that interest rates have declined in the last four decades in advanced

economies and their central banks have had to adjust.

Indeed, according to the current macroeconomic consensus, the steady-state level of central bank

policy rates should be guided by the so-called neutral rate, i.e. the real rate compatible with inflation

around target and output at potential, which is driven by fundamental factors including productivity,

demographic growth and the saving behaviour of households. This rate is not directly observable, and

its measurement is highly uncertain, but most estimates point towards a significant decline in the

neutral rate, in particular since the global financial crisis (see, for example, the estimates of Holston et

al., 2016, in Figure 1 panel A). If a central bank’s reaction function can be characterised through a simple

Taylor rule

2

, with a neutral rate close to 0% and an inflation target of 2%, this means that the ECB’s

nominal steady-state policy rate would be around 2%, leaving the ECB without enough conventional

ammunition to face shocks, given that historically, central banks have cut rates by around 300 bps

during recessions

3

.

As a result, if the neutral rate were to remain at a low level, unconventional tools, and possibly NIRP,

would have to be used often in order to make monetary policy accommodative enough when there is

slack in the economy and inflation is below target. Actually, markets currently believe that the

overnight interest rate in the euro area will stay negative at least until 2026 (Figure 1, panel B).

2

The basic Taylor rule, following Taylor’s original specifications and coefficients (Taylor, 1993), looks like this: r=inflation+r*+0.5(inflation-

target) +0.5(output gap)

3

The US Fed cut its policy rates on average by 330 basis points during recessions from 1920 to 2018, the Bank of England by 290 bps from

1955 to 2018, and the central bank for Germany (the Bundesbank followed by the ECB) by 260 bps from 1960 to 2018 (Bruegel calculations

based on OECD, Fed, BoE and Bundesbank).

What Are the Effects of the ECB’s Negative Interest Rate Policy?

9 PE 662.922

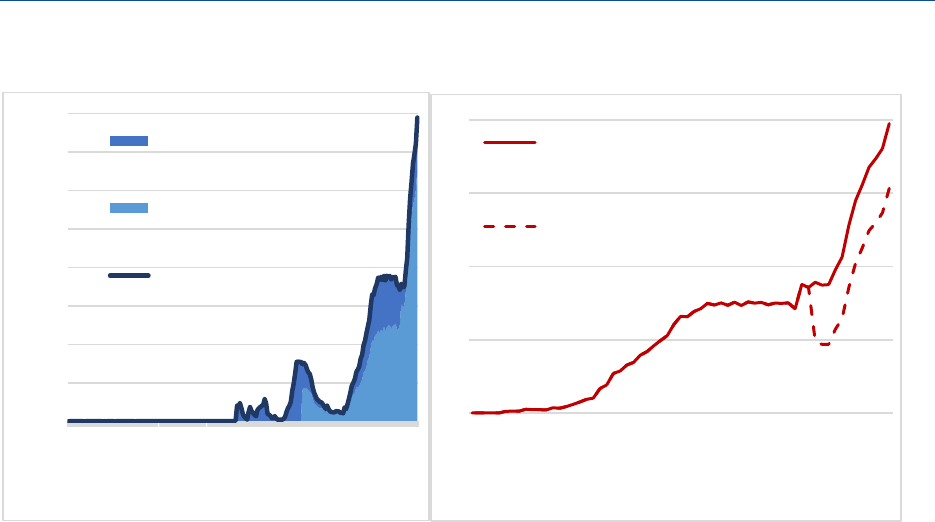

Figure 1: Interest rates

Panel A: Neutral real rate estimates (%) Panel B: expectations for euro area overnight rate (%)

Note: Interest rate expectations as of May 2021, derived from EONIA zero-coupon swaps of different terms (1 year, 2 years, up

to 10 years), which provide information on market expectations of the compounded overnight EONIA over the contract term.

Expectations for 2022 interest rate, for instance, are derived through expected compounded EONIA over the next year (2021),

given by the 1-year swap, and expected compounded EONIA over the next two years (2021 and 2022), given by the 2-year

swap.

Source: Panel A: Holston et al. (2016), updated in 2021. Panel B: Bruegel based on Bloomberg.

If NIRP becomes an often-used monetary policy tool, it is crucial to fully understand the effects on the

economy of prolonged negative rates. Central banks which have been part of this experiment are

generally positive (see e.g., Schnabel, 2020) about the use of negative rates in helping them fulfil their

objectives (whether it is to bring inflation towards target, as in the euro area or in Sweden, or to stabilise

the exchange rate as in Denmark or Switzerland). However, NIRP remains controversial and has been

accused of causing significant side effects in particular for the banking sector. As a result, two major

central banks, the US Fed and the Bank of England (BoE), have refrained from using that tool despite

facing the same crises as the countries that have resorted to it.

This is because the effects of NIRP could be different to those of traditional rate cuts in positive territory,

and the net effect could more be ambiguous because of the presence of various frictions in the

economy: the existence of cash yielding a 0% nominal interest rate, cognitive biases of investors and

households, and financial and legal constraints. In this paper, we first look at the potential effects of

negative rates and describe the potential mechanisms at work when this measure is used (section 2),

before turning to the evidence (section 3). We conclude with a discussion on what the ECB can do to

reduce or avoid potential side effects (section 4).

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

1961

1965

1970

1974

1979

1983

1988

1993

1997

2002

2006

2011

2016

US Euro Area

-1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

2001

2003

2006

2008

2011

2013

2016

2019

2021

2024

2026

2029

EONIA

(realised)

EONIA

(expectations)

IPOL | Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies

PE 662.922 10

EFFECTS OF CENTRAL BANK NEGATIVE RATES IN THEORY

2.1. Potential positive effects on lending, output and ultimately inflation

First, NIRP is the logical extension of the main monetary policy tool used in the two decades that

preceded the financial crisis: rate cuts. Compared to quantitative easing (QE), the transmission channels

for which are relatively complex, or to forward guidance, which relies on the role played by

expectations (and which could be fraught with time-consistency issues), NIRP is the most conventional

of the unconventional tools introduced since the financial crisis, and a much more mechanical tool.

Indeed, the main transmission channel of NIRP to the economy should be very similar to that of

traditional rate cuts. When needed, central bank rate cuts provide monetary accommodation through

the easing of financing conditions, which tends to boost credit demand for investment and

consumption, provide some fiscal space to governments, and thus increase aggregate demand and

inflation. Negative policy rates, as long as they are transmitted to bank and market rates, are supposed

to function in the same way.

However, the existence of various frictions (e.g. physical cash yielding a 0% nominal interest rate and

possible cognitive biases) means that going below 0% could lead to additional channels and non-

linear effects of monetary policy at the “zero lower bound” (ZLB), or more precisely at the “effective

lower bound” (ELB), which could be slightly below 0% because of the cost of cash storage. There could

therefore be several additional channels of central bank policy rate cuts in negative territory.

First, going negative could have a stronger impact on the whole yield curve. The reason is that

breaching the ZLB for the first time and/or announcing that negative rates will be part of the central

bank toolbox in the future, could lead investors who might not have thought negative rates were

possible to revise their expectations about what minimum rates can be in the future (by removing

any non-negativity restriction), and thus reduce rates along the whole yield curve.

Second, the traditional portfolio rebalancing effect that already exists with standard rate cuts

(pushing investors towards riskier assets in a search for yield) could be boosted by the aversion of some

investors to negative rates. This could be for contractual reasons, for instance if redemption at par is

guaranteed on some savings products. It could also be for behavioural reasons if economic agents

(households or corporations) are subject to some form of loss aversion. This could, for instance, lead

cash-rich corporations to increase fixed investment to avoid negative rates. At the bank level, portfolio

rebalancing could also be boosted by negative rates because of a “hot-potato” effect pushing banks to

purchase various assets in order to shift negative-yielding reserves to other banks (even if the

aggregate level of reserves cannot be controlled by banks and is now mainly determined by the pace

of ECB asset purchases).

Third, the exchange rate channel, which matters a lot in small open economies like Denmark, Sweden

and Switzerland, could also be stronger when rates are negative. Conventional rate cuts influence

exchange rates through the interest rate parity: a negative expected interest rate differential with

partners leads to a depreciation of the currency, which in turn tends to boost exports and increase the

price of imports, therefore impacting positively output and inflation. This effect could be increased if

cross-border capital flows are more sensitive to negative rates (again because of investors’ aversion to

them and greater portfolio rebalancing effects). In fact, this is how Denmark justified the introduction

of NIRP, as a tool to defend its peg with the euro, at a time when inward capital flows (because Denmark

was perceived at a safe haven during the euro crisis) were leading to an appreciation of its currency

that could have hampered its exports and reduced inflation below a desired level.

What Are the Effects of the ECB’s Negative Interest Rate Policy?

11 PE 662.922

Finally, if all these positive effects were to materialise and result (after also taking into account potential

negative effects discussed below) in an improved macroeconomic outlook, general equilibrium

effects may also have knock-on benefits for banks’ profitability. Higher economic activity could lead to

an increase in the demand for credit and in banks’ non-interest income, but it would also improve their

borrowers’ creditworthiness, thereby improving the credit quality of their assets and reducing non-

performing loans and loan-loss provisioning. Moreover, capital gains derived from the increase in the

value of the securities held by banks would increase their net worth and increase their distance to

default (as discussed by Chodorow-Reich, 2014). This improved health of the banking sector could in

turn enhance the ability of banks to finance the economy.

2.2. Possible negative side effects for the financial sector

Most criticism of negative rates focuses on the potential negative side effects for the financial sector,

which could at some point hinder the crucial role the sector plays in financing the economy.

First, it is true that a negative deposit facility rate represents a direct cost for banks that hold reserves

above the minimum reserves required by the central bank. The problem for banks is that with the

adoption of various asset purchase programmes, on aggregate, the banking sector is flooded with

excess liquidity and cannot avoid that cost.

However, although banks’ reserves at the ECB have increased very significantly in recent years, they

still represent a relatively limited share of the total assets held by banks in the euro area. What really

matters is thus not only the direct cost of these reserves held at the ECB, but how negative rates

influence other components of banks’ balance sheets that could reduce their overall profitability.

Indeed, negative rates could also lead to a potential decline in net interest income of banks if there

is a non-linear threshold effect at the ZLB (or near it, at the ELB). This would happen if the returns on

their assets are reduced (even more so because negative rates have led to a flattening of the curve, as

discussed above), while the policy rate cut does not fully translate into a fall in the interest rates paid

on their liabilities, because of a downward rigidity of deposit rates below 0%.

This could happen if banks are reluctant to pass on negative rates to deposits because they fear

households or corporations will start to hoard cash or move their accounts to another bank to avoid

negative rates. A reduction of net interest margins of banks could then lead either to reduced lending

volumes or to more expensive lending, as banks try to pass the cost of negative rates to their customers

to restore their intermediation margins. Both possibilities would reduce the transmission of the

monetary policy easing to the real economy. However, as discussed before, this could in part be

compensated for by the positive macro impact on lower rates that could lead to a reduction in non-

performing loans and to an increase in asset values held by banks, which would improve the banks’

financial health. Which effect dominates is not clear in theory and is ultimately an empirical question.

Negative rates could also impact non-bank financial institutions such as money market funds. Their

business model (i.e. issuing short-term, very liquid, almost cash-like, liabilities to invest in liquid safe

assets) could be particularly compromised by the combination of negative rates and a flattening of the

yield curve, given their already thin interest margins.

Finally, another important potential side effect is simply the corollary of the increase in the portfolio

rebalancing effect: an increase in risk-taking by banks and by other financial institutions such as

insurance companies, could if it becomes excessive lead to the emergence of bubbles and financial

instability episodes. This is a crucial element to take into account as this could make the use of

negative rate counterproductive in the long run, even if positive effects dominate in the short run.

IPOL | Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies

PE 662.922 12

2.3. Possible reduced response of economic activity to interest rates

Conventional monetary policy, as it has been applied by all major central banks in the last decades,

relies on the conjecture that reducing nominal rates stimulates economic activity (see e.g., Woodford,

2003). This notion is also what supports the use of negative rates, if the fall in the policy rate passed to

market/bank rates then translates to higher demand for credit for consumption and investment, and

thus to increased output and inflation (as discussed in section 2.1). This is the idea behind the neutral

rate discussed above: as long as the central bank can reduce interest rates sufficiently (either through

standard rate cuts, or through negative rates, QE or forward guidance when the ZLB is reached) it

should be able to bring inflation back towards target and ensure that the economy is at full

employment. The question in that case is more how to go sufficiently low than whether it can be done.

However, after years of too-low inflation, the idea that such a neutral rate can be reached is now being

questioned. Maybe full employment and targeted inflation cannot be attained through the lowering

of rates only, without the support of other policies (fiscal and structural). This could be the case either

because the “reversal rate”

4

, at which negative effects start dominating, would be above the

presumptive neutral rate, or more simply because the sensitivity of output to interest rates would not

be as large as usually considered.

There could be multiple reasons behind this (Stansbury and Summers, 2020). The sensitivity of output

and inflation to interest rate cuts could be lower than it used to be because of sectoral changes in the

economy (towards less interest-sensitive sectors), or because fixed-capital investment is less sensitive

than before (e.g., because intangible capital depreciates more quickly and needs to be replaced often

whatever the interest rate is)

5

. It could also be diminished when rates are low or negative (e.g., because

some households target a minimum level of savings which is negatively affected by low rates

6

). The

responsiveness of output to rates could also be reduced during recessions (if firms are too pessimistic

about future demand). Or it could also decrease after a period of prolonged low rates (for instance

because demand for durable goods or housing is satiated or because agents are already overly

indebted). Finally, the response of the real economy to rates could be asymmetric: economic agents

might react differently to rate increases than to rate cuts (e.g., because credit constraints become

binding when central banks tighten their policies). For all these possible reasons, negative rates (and

monetary policy in general) could be an insufficient tool to achieve full employment and price stability.

4

An expression coined (and a concept formalised) by Brunnermeier and Koby (2018).

5

Or, as discussed by Geerolf (2019), it could be that fixed capital investment has never really been sensitive to interest rates and that firms

invest only when they need to produce more to meet increasing expected demand, as posited in the accelerator model of investment.

6

Guerrón-Quintana and Kuester (2019), exploring the implications of pension systems for the design of monetary policy, show that if the

public pension system is not generous enough, low for long interest rates can reduce aggregate activity.

What Are the Effects of the ECB’s Negative Interest Rate Policy?

13 PE 662.922

EFFECTS OF CENTRAL BANK NEGATIVE RATES IN PRACTICE

In practice, these various effects, positive and negative, coexist. Which one dominates depends on

multiple parameters, including in particular the magnitude of negative rates. The ‘reversal rate’

represents the interest rate at which negative effects start dominating and at which further rate cuts

become counterproductive and contractionary

7

.

However, this will also depend on structural features of the economy: the prominence of banks in the

financial sector (vs markets), the financial structure of banks, the aversion of households and the

behaviour of non-financial corporations with respect to negative rates, the costs of holding cash

(storage, transportation, insurance, but also the convenience of electronic payments provided by bank

deposits), etc. This means that the net effect of negative rates is probably time- and country-specific. In

this section, we look at the evidence to see what the effects of negative rates have been in practice in

the euro area since their introduction in 2014.

3.1. Transmission to market (interest and exchange) rates

How have negative policy rates been transmitted to the main benchmark market rates? Given the

abundance of liquidity in the euro area’s banking sector due to the introduction of a very large amount

of reserves by the ECB through its various refinancing operations (LTROs and TLTROs) and asset

purchase programmes (in particular since 2015), the deposit facility rate has de facto become the main

ECB policy rate influencing market rates. As far as the short-term rate is concerned, we observe a full

pass-through from the ECB’s deposit facility rate to the operational target rate of the ECB, the

EONIA (replaced recently by the €STR). As Figure 2 Panel A shows clearly, breaching the ZLB did not

affect the transmission from the policy rate to the overnight rate (on the contrary, it even appears that

the volatility of the EONIA has been reduced).

Concerning the rest of the yield curve, a fall in long-term yields of euro area countries is visible to the

naked eye in Figure 2 Panel B after the introduction of negative rates, suggesting that this has led

investors to revise their expectations about the possible future path of policy rates. This observation is

confirmed formally by the literature. Christensen (2019), who studied the reaction of markets rate in all

countries that have adopted negative rates, found that the entire cross section of government bond

yields exhibits an immediate, significant, and persistent response to the introduction of negative

rates, with a maximum impact on yields with a maturity of 5 years. Rostagno et al. (2021) confirmed

that the negative ECB rate propagated across the whole sovereign yield curve. According to them, the

response of long-term rates to the NIRP even surpasses the response to conventional rate cuts by a

wide margin.

7

The concept of “reversal rate” is related but different from the concept of ELB, as the latter represents the interest rate at which agents

are indifferent between holding deposits and cash and which should be slightly negative to account for the costs/risks of holding cash.

The level of the reversal rate could thus be above or below the ELB.

IPOL | Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies

PE 662.922 14

Figure 2: Policy and market interest rate in the euro area

Panel A: ECB rates and EONIA (%) Panel B: Government bond yields: 10-year (%)

Note: black vertical line indicates the introduction of NIRP in the euro area in June 2014.

Source: Bruegel based on ECB and FRED (https://fred.stlouisfed.org

).

On the effects of negative rates on the exchange rate, although their introduction was followed by a

strong depreciation of the euro clearly visible in Figure 3, the evidence from the literature is mixed.

While Hameed and Rose (2017) did not find a significant impact of NIRP on the evolution of the

exchange rate, it appears that in Denmark and Switzerland the appreciation of their respective

currencies was halted by the introduction of negative rates, which led to an adjustment in cross-border

bank flows (see Khayat, 2018, on Denmark; Basten and Mariathasan, 2018, on Switzerland). More

generally, Ferrari et al. (2017) also showed that the sensitivity of exchange rates to changes in policy

rates is stronger when rates are lower.

Figure 3: Euro nominal effective exchange rate

Notes: Index 2010 = 100. Nominal effective exchange rates are calculated as geometric weighted averages of bilateral

exchange rates. Black vertical line indicates the introduction of NIRP in the euro area in June 2014.

Source: Bruegel based on BIS and retrieved from FRED (https://fred.stlouisfed.org

).

-1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

1999

2001

2003

2005

2007

2009

2011

2013

2015

2017

2019

2021

Deposit Facility Rate

Marginal Lending

Rate

Main Refinancing

Rate

EONIA

-2

-1

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

2013

2013

2014

2015

2015

2016

2017

2017

2018

2019

2019

2020

2021

Spain Germany

France Portugal

Euro area Italy

90

95

100

105

110

115

2004

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2019

2020

What Are the Effects of the ECB’s Negative Interest Rate Policy?

15 PE 662.922

3.2. Effects of negative rates on banks

3.2.1. Direct cost of a negative deposit facility rate for euro-area banks

First, as its name suggests, a negative deposit facility rate implies a direct cost charged on excess

liquidity deposited by commercial banks at the ECB. In the first decade of the euro, banks did not hold

excess liquidity at the ECB and held only enough reserves to fulfil the reserves officially required by the

central bank (Figure 4 panel A).

However, with the financial crisis and the COVID-19 crisis, the ECB injected a very large quantity of

reserves into the banking sector. Total reserves of banks at the ECB went up from around EUR 10 billion

at the beginning of 1999 (compared to total assets of euro area banks of EUR 14 trillion, i.e. 0.7%) to

above EUR 4 trillion in April 2021 (compared to total assets of EUR 36 trillion i.e. 11.3%).

At first, the ECB injected reserves mainly through refinancing operations (MROs and then LTROs). This

meant that the banks could control the quantity of reserves they wanted to hold because they were

given the choice to participate in these operations. Thus, that before the financial crisis, no bank sought

to hold reserves above what was required (see Figure 4 panel A). During the financial crisis (2008-12),

some banks decided to hold extra reserves to insure themselves against possible liquidity shortages,

but gradually reduced these holdings after the euro crisis ended. Nevertheless, with the launch of the

public sector purchase programme (PSPP) in 2015, banks lost control of the aggregate level of reserves.

Since then, this level is fully determined by the ECB because central bank reserves created for the

purchases inevitably end up as deposits in a bank. With the addition of the pandemic emergency

purchase programme (PEPP) in 2020, excess liquidity is now quickly approaching EUR 4 trillion (Figure

4, panel A).

As a result, the direct cost of holding excess liquidity for banks has also risen significantly. After

levelling off at about EUR 7.5 billion annually between 2017 and 2019, the ECB decided in September

2019 to put in place a “two-tier system” by exempting part of the excess reserves from the negative

deposit rate (equal to six times required reserves). This led to a significant fall in the direct cost incurred

by banks, from around EUR 8.5 billion to EUR 4.6 billion. However, with the launch of the PEPP in March

2020, the cost for banks (even with tiering) has now increased to around EUR 15 billion per year (Figure

4 panel B).

IPOL | Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies

PE 662.922 16

Figure 4: Excess liquidity held at the ECB and direct costs for the banks of the euro area

Panel A: Excess liquidity (in EUR bn) Panel B: Direct cost of negative DFR for banking sector (in EUR bn)

Notes: Excess liquidity is defined as deposits at the deposit facility net of the recourse to the marginal lending facility plus

current account holdings in excess of those contributing to the minimum reserve requirements. Direct cost is measured as

the excess liquidity (as defined in Panel A) x (- deposit rate). Direct cost net of tiering is measured as direct cost - tiered reserves

x (- deposit rate), with tiered reserves = excess liquidity exempted from negative rates, i.e., 6 times required reserves of the

whole banking sector since June 2019 and 0 before tiering was introduced.

Source: Bruegel based on ECB.

Moreover, this cost is unevenly distributed across the euro area (Figure 5 Panel A) and is mainly

concentrated in Germany, France, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Finland (up to 95% of the cost

was incurred in these countries in July 2019, but it is down to 72%). As discussed in Darvas and Pichler

(2018), the main reason why excess liquidity is concentrated in these five countries is that for a large

share of asset purchases made by the ECB counterparties have headquarters outside of the euro area

and their euro liquidity is parked in bank accounts in a few euro area financial centres.

In some countries these costs represent a non-negligible share of the profits generated by European

banks (Figure 5 Panel B). However, again, the share of profits that these costs represent varies greatly

across the euro area. In that regard, the comparison between France and Germany is enlightening. Even

though the banks from these two countries both represent a high share of excess reserves and thus

bear a high cost, the situation is very different when these costs are compared to the profits generated

by their banking sectors. While the cost associated with the negative deposit facility rate of the ECB

represented 28.2% of the profits of German banks, this only represented only 4.8% of the profits of

French banks in 2019. This suggests that a negative deposit facility rate is not the main driver of the

low profitability of banks in some countries, but that there are some structural (efficiency) issues

affecting the banks’ profitability in these countries.

0

500

1.000

1.500

2.000

2.500

3.000

3.500

4.000

2021-Apr

2019-Apr

2017-May

2015-Apr

2013-Nov

2012-Jul

2011-Mar

2009-Nov

2008-Jul

2007-Mar

2005-Nov

2004-Jul

2003-Feb

2001-Oct

2000-Jun

1999-Feb

Deposit facility

Excess reserves on current

account facility

Excess liquidity

0

5

10

15

20

2021-Apr

2020-Nov

2020-May

2019-Oct

2019-Apr

2018-Oct

2018-May

2017-Oct

2017-May

2016-Oct

2016-Apr

2015-Oct

2015-Apr

2014-Nov

2014-Jul

2014-Mar

direct cost of negative

deposit rate on excess

liquidity

direct cost net of tiering

What Are the Effects of the ECB’s Negative Interest Rate Policy?

17 PE 662.922

Figure 5: Direct cost of a negative deposit facility rate per country

Panel A: Annualised direct cost per country (in EUR millions)

Panel B: Direct cost per year and per country compared to profits (in EUR millions and % of profits)

Notes: Direct costs are calculated in the same way as in Figure 4. Profits are derived indirectly through the return on equity of

banks.

Source: Bruegel based on ECB.

The only way for banks to circumvent the cost related to a negative DFR is to convert ECB reserves into

cash. Actually, cash held by monetary and financial institutions in the euro area has increased since

the ECB started imposing a negative rate on excess reserves. Nonetheless, amounts are still marginal

compared to excess reserves, and the movement is still mainly circumscribed to German banks (ECB,

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

10000

12000

14000

16000

Austria Belgium Cyprus Germany Estonia

Spain Finland France Greece Ireland

Italy Lithuania Luxembourg Latvia Malta

Netherlands Portugal Slovenia Slovakia

IPOL | Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies

PE 662.922 18

2018). This probably means that the policy rate is still above or around the ELB

8

. This remains a fairly

limited phenomenon at the moment, but if this shift towards cash becomes more widespread, it could

reduce the transmission from policy rates to the overnight market rate.

3.2.2. Impact on other components of the balance sheets of commercial banks

However, even if the share of excess reserves on the banks’ balance sheet has increased considerably

in the last 10 years, it is still relatively limited (at around 11%). The costs associated with excess reserves

could thus be manageable if the maturity transformation business model of banks is not affected by

negative rates. Indeed, a compression of the spread between credit and deposit rates and a

general flattening of the curve, which reduce the returns from maturity transformation, would be

much more damaging for the banks’ overall profitability than the mere negative DFR imposed on

excess liquidity.

How has the negative policy rate been transmitted to the euro-area banks’ rates? In order to answer

this question and determine if the net interest margins of banks have been compressed, we look

separately at the rates on loans and on deposits for both households and corporations. Figure 6

displays these four different bank rates. It is difficult to see precisely with the naked eye how policy

rates influence these bank rates and if the effects change below the ZLB/ELB, but our simple

econometric analysis (see Box 1 for details) confirms that in general the pass-through is incomplete for

all interest rates. In other words, a 1-point decrease in the policy rate (proxied by the EONIA) does not

fully translate into a 1-point decrease in bank rates. But we find that the pass-through is significantly

higher for rates on banks’ assets (loans) than on their liabilities (deposits). It is also higher for

corporations than for households (see detailed results in Table 2).

Overall, our results imply that rate cuts indeed compress banks’ interest margins. However, we also

check if the relationships change when the EONIA becomes negative (and when the EONIA falls below

other more negative thresholds down to -0.5%) and we fail to find any evidence of a non-linearity of

this effect below 0%. In other words, monetary policy easing appears to have a negative impact on

banks’ net interest margins (at least directly, because indirectly an improvement in the economy due

to the easing could counterbalance this effect in the medium to long run

9

), but rate cuts in negative

territory do not seem to amplify this negative impact on banks’ margins in a significant way.

8

This would be compatible with the estimation of the ELB at -0.7% by Rostagno et al. (2016) based on the cost of holding cash at 0.4% plus

some extra inconvenience of transacting in cash.

9

One important channel leading to the improvement at the macro level is that the banks’ loss of interest margins represents a gain for

households and corporations which can borrow more cheaply, while the rate on their deposits do not fall as much.

What Are the Effects of the ECB’s Negative Interest Rate Policy?

19 PE 662.922

Figure 6: Composite bank interest rates for households and corporations (%)

Notes: Rates are weighted averages of rates applied by maturity/type of loan. For instance, "Household Deposit Rate" is an

average of the annualised agreed rates with maturities below and above 2 years weighted by outstanding amounts remaining

at the end of the periods. See details in box 1. Black vertical line indicates the introduction of NIRP in the euro area in June

2014.

Source: Bruegel based on ECB.

The fact that rates on households’ deposits are still above 0% is generally interpreted as a non-linearity:

banks are not passing negative rates to households’ deposits because they are afraid of cash

withdrawal (because cash cannot be submitted to negative rates). But it is also possible that this rate is

still above 0% because of its usual stickiness. Rate cuts, which are generally passed more quickly to

corporate deposits, have actually led some banks to impose negative rates on their deposits despite a

similar risk of cash hoarding for non-financial corporations (NFC) than for households: the average euro

area rate on NFC’s overnight deposits is still positive, but the averages in Germany and in particularly

the Netherlands are negative (Schnabel, 2020).

Concerning cash hoarding, as seen earlier, the conversion of reserves into cash by banks is still

marginal. This is also true for deposits of households and corporations. Cash hoarding is not happening

yet, probably because the negative rate applied to deposits is still lower than the cost of storing cash

and because of the convenience of bank deposits and electronic payments (especially with the recent

increase in online shopping).

Nevertheless, our results also mean that the effect of rate cuts (whether below or above the ZLB) on

banks will depend on their financial structures, and in particular on the composition of their assets

and liabilities (which differs across banks and across countries): if a bank is heavily reliant on

households’ deposits and if lending rates to households and corporations decrease more steeply than

the rates applied to deposits, then its net interest income will be particularly reduced.

The literature generally shows that, on average in the euro area, banks’ overall profitability has not been

particularly affected by the introduction of negative rates (Jobst and Hin, 2016; Stráský and Hwang,

2019) in part because increased asset values and stronger economic activity have offset the negative

effects. But the literature also suggests that banks with higher shares of households’ deposits have

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

2003

2003

2004

2005

2005

2006

2007

2007

2008

2009

2009

2010

2011

2011

2012

2013

2013

2014

2015

2015

2016

2017

2017

2018

2019

2019

2020

2021

EONIA

Corporate Loans Interest Rate

Household Loans Interest Rate

Household Deposits Interest Rate

IPOL | Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies

PE 662.922 20

either seen their profitability more affected by the fall in rates (Heider et al., 2019) or that they have not

passed the rate cuts to their loans to try to compensate (Amzallag et al., 2019).

Box 1: Estimating the pass-through of monetary policy to bank rates

In order to assess the impact of changes of central bank policy rates to bank rates, we first construct

composite interest rates for households and corporations on loans and deposits. Using ECB data, we

weight various interest rates with different maturities and destination of use (e.g., loans for house

purchase with a maturity of more than 10 years) by the importance of its amount of relative to its

category (other loans made to households).

This provides us with four composite time series of interest rates for the euro area. Next, we explore

the relationship between the monetary policy rate (proxied by the EONIA) and these different bank

rates. First, we estimate the long-run relationship between the two variables with the following

regression:

= +

+

where

is a given bank rate (e.g., loans for households),

is the monetary policy rate (proxied here

by the EONIA). The table below summarizes the results for all four types of interest rates.

Table 1: Relationship between monetary policy rate and banking rates

Household

Deposits

Corporate

Deposits

Household

Loans

Corporate Loans

0.46***

0.73***

0.92***

0.92***

*** statistically significant at the 1% threshold

Source: Bruegel.

The results indicate that the pass-through is incomplete for all interest rates. In other words, a 1-

point decrease in the policy rate is not translated into a 1-point decrease of banking rates. In addition,

these results indicate that the pass-through is significantly higher for rates applied on banks’ assets

(loans) than on their liabilities (deposits). Similarly, the pass-through is higher for corporations than

for households.

Next, we look at the short-term effect of changes in the policy rate on bank rates in order to assess

whether this relationship has changed since rates are negative. We estimate the following

regression:

=

+

+

+

+

+

(

×

) +

where

=

for =

{

,

}

and (

) is a vector with the error terms of equation 1

(in other words the difference between the actual value of the given bank rate in t-1 and the

predicted bank rate estimated above).

is a dummy variable equal to 1 when the policy rate is

below 0, making

(

×

)

the interaction variable between changes in the policy rate when

the rate is negative. In other words,

captures the effect of a change in t-1 of the monetary policy

What Are the Effects of the ECB’s Negative Interest Rate Policy?

21 PE 662.922

rate on changes in the bank rate and

the additional effect when the rate is negative. If

is not

null and statistically significant, this would mean that the pass-through changes when rates are

negative.

Table 2: Relationship between and banking rates in case of negative rates

Household

Deposits

Corporate

Deposits

Household

Loans

Corporate Loans

0.46***

0.73***

0.92***

0.92***

Short-term effect

(

)

0.07*** 0.18*** 0.34*** 0.52***

Additional effect

when rates are

negative (

)

-0.01 -0.27 -0.6 -0.65

***, ***, *: statistically significant at the 1%, 5% and 10% threshold respectively.

Source: Bruegel.

While the coefficients of the short-term changes in the policy rate confirm that the pass-through is

stronger for banks’ assets (loans) than for their liabilities (deposits) as well as for corporate rates, the

effect of the interaction variable is not statistically significant. This suggests that there is no change

in the relationship between the policy rate and bank rates when the policy rate is negative. In other

words, nothing indicates the presence of non-linearity of the effect below the threshold of zero. We

test other thresholds by steps of 10 bps below 0% (-0.1%, -0.2%, etc.) and find similar results.

What has been the effect on banks’ lending volumes? Whether for households or NFCs, lending has

grown steadily from the introduction of negative rates to the COVID-19 crisis (Figure 7)

10

. However, it

is extremely difficult to disentangle the effect of NIRP from other potential drivers. Part of this strong

growth can surely be explained by the recovery that took place in the euro area from 2014 to 2020

(which increased demand for loans), but at least at the aggregate level, we observe neither reduced

lending nor an increase in rates to compensate for lost profits (Figure 6). This suggests, at first sight,

that in terms of bank lending volume, the economy has reacted to negative rates similarly than to rate

cuts in positive territory. The results from the literature on that question are mixed, but some studies

confirm that banks have indeed increased lending volumes after the introduction of negative rates, in

particular banks that rely less on deposits (e.g. Heider et al., 2019).

10

The data after March 2020 is clearly influenced by economic policies (e.g. government guarantees on bank loans) and lockdowns put in

place to respond to the COVID-19 crisis which have respectively led to high borrowing from firms and low borrowing from households

for consumption.

IPOL | Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies

PE 662.922 22

Figure 7: Bank lending to the private sector in the euro area (YoY, %)

Note: black vertical line indicates the introduction of NIRP in the euro area in June 2014.

Source: Bruegel based on ECB.

To conclude on the effects of negative rates on banks, there are nevertheless two important caveats.

First, the evidence discussed and the literature (in the euro area but also in other jurisdictions that have

adopted NIRP) has been gathered with negative rates relatively close to 0%. This means that a strong

non-linearity could still arise at lower rates. Second, the impact on banks could also vary over time.

Effects of prolonged negative rate could be different: at the beginning, the effect is positive as the one-

off mark-to-market revaluation dominates, but, if negative rates are prolonged, maturing assets are

gradually replaced by low-yielding loans, which could lead to a persistent decline in interest margins.

In addition, the reduction of net interest income compensated for at the beginning by higher volumes

and increased fees might not last (or banks will have to adjust their business model in order to rely

more on fees than on interest margins).

3.3. Macro and financial stability impact

This is undoubtedly the most difficult and the most crucial question to answer. There is now a fast-

expanding literature on the effects of negative rates, but it has not yet led to a clear consensus on the

macro effect of negative rates or on its long-term effects on financial stability.

It is still very difficult to measure precisely the macro effects of NIRP for various reasons. First, various

other unconventional measures were implemented at the same time and are difficult to disentangle

from negative rates. Second, NIRP was only adopted in a few countries. And, finally, there could also be

a possible selection bias, as central banks that that have concluded less favourable cost-benefit

analyses might have decided not to use NIRP (this could be the case with the Fed and the BoE).

On the macro effects, ECB papers are generally (and not surprisingly) positive about the effects of

NIRP. They generally find a positive (although not very high) impact of negative rates on output,

employment and inflation compared to a counterfactual without negative rates (see Figure 8 borrowed

from Rostagno et al., 2021), and that the reversal rate is not yet a valid concern in the euro area at this

stage.

-6

-4

-2

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

Loans to non-financial corporations

Loans to households (consumption)

Loans to households (house purchase)

What Are the Effects of the ECB’s Negative Interest Rate Policy?

23 PE 662.922

Figure 8: Estimated impact of three ECB rate cuts (by 10 bps) on macro variables

Notes: Their analysis is based on a Bayesian vector autoregression (BVAR) model with 17 variables and a dense, controlled

event-study approach to identification. The shaded area reflects the dispersion of the median responses obtained over the

simulation samples. See Rostagno et al. (2021) for details on the methodology used.

Source: Figure 12.1 from Rostagno et al. (2021).

However, other papers are more doubtful about the positive macro effects of negative rates, especially

in the long run. Stansbury and Summers (2020) in particular documented extensively all the possible

reasons why the sensitivity of output, employment and inflation to interest rates might have

declined in recent decades, and why this could run counter to the argument for negative policy rates.

The sum of evidence collected by the authors is definitely thought-provoking, but it does not provide,

at this stage, a clear picture and a quantification of the overall macro effect. Moreover, the evidence

collected is mainly about the US and could be very different in Europe given the massive differences in

the functioning of the two economies, e.g. in the financial sector, in the housing market, in the social

safety net and pension systems, and in households’ behaviours.

Nevertheless, one particular reason why negative rate could be counterproductive is if low and

negative rate were to have long-term consequences for financial stability and lead to the formation of

bubbles and ultimately to financial stress episodes. There is strong evidence that financial institutions

in the euro area have increased their risk taking and have engaged in search-for-yield as a result of

negative rates (Bubeck et al., 2020; Heider et al., 2019). However, as discussed earlier, increasing risk-

taking and pushing financial institutions to rebalance their portfolios is essentially a feature not a bug

of accommodative monetary policy, but it is very difficult to say if/when this additional risk-taking

becomes excessive.

IPOL | Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies

PE 662.922 24

CONCLUSIONS: WHAT DO WE KNOW AND WHAT SHOULD THE

ECB DO?

Despite the burgeoning literature, the debate on the effects of NIRP is not yet fully settled.

Nevertheless, we have already learned a few things about how negative rates work. First, the

experience of the euro area since 2014 shows that the negative deposit facility rate is fully transmitted

to the benchmark overnight rate and then propagates along the whole yield curve. Second, there is

also some evidence (in particular from Denmark and Switzerland) that NIRP also impacts the exchange

rate through a change in cross-border flows. Third, as far as bank rates are concerned, despite some

concerns about a stronger negative impact of NIRP on net interest margins and banks’ profitability, it

appears that the effects of rate cuts in negative territory are not different to “standard” rate cuts. Like

them, they reduce banks’ interest margins because rates on banks’ assets are more sensitive to policy

rates than rates on banks’ liabilities, but this effect does not appear to be amplified below 0% (at least

at the current relatively low level of negative rates). Finally, a negative deposit facility rate implies some

cost for banks that hold excess reserves at the ECB. This cost has been growing significantly, in

particular since the introduction of the PEPP in 2020. Moreover, this cost is concentrated in the

countries that host the main European financial centres (where investors which have sold assets to the

ECB park their euro deposits). In some of these countries, Germany in particular, where the banking

sector is not as profitable as in other jurisdictions, this direct cost can represent a significant share of

banks’ profits (28% in 2019 in Germany). However, other examples, such as France, show that if the

banking sector is sufficiently profitable, the cost as a share of profits remain small (4.8% in 2019).

A more difficult and more fundamental question about negative rates, and for monetary policy in

general at this stage, is whether output, employment and inflation are still as sensitive to these

financial variables as they used to be when rates are very low or even negative. The ECB’s own

research is confident that the effect of NIRP on these variables in the short- to medium-term is positive

at this stage. Potential negative side effects do not appear to have materialised in a significant way for

the moment, which might mean that the ECB rate is still above the reversal rate. However, a long period

of negative rates could also entail some medium- to long-term risk, in particular in terms of financial

stability. Financial institutions seem to have increased their risk-taking with the advent of negative

rates. Whether this risk-taking is excessive remains to be seen and will need to be monitored carefully.

What should the ECB do at this stage? The ECB, like other central banks which have adopted NIRP, will

need to continue to monitor carefully the potential side effects, see if its policy rate approaches the

reversal rate, or even if this reversal rate is evolving (and potentially increasing) as negative rates are in

place for a prolonged period, in order to update its cost-benefit analysis.

The direct cost incurred by banks that hold excess reserves appears to be one of the most tangible side

effects at this stage. So, the first thing the ECB could do is to mitigate this visible side effect (which is

problematic in a few countries and which makes this policy very unpopular despite its potential

benefits). The easiest solution would be to adjust the two-tier system put in place in 2019 and to

increase the quantity of excess reserves that are exempted from the negative deposit facility rate

(currently equal to six times required reserves). Potentially, the ECB faces a trade-off between

mitigating the direct cost for banks and reducing the influence of the deposit facility rate on short-term

market rates if too much reserves are exempted. However, for the moment, despite the current tiering,

the overnight rate continues to trade near the DFR. The ECB could thus experiment and try to increase

the level of exempted reserves in a gradual way (for instance by raising the tiering multiplier from 6

to 8) to see if this trade-off materialises and if the influence of the DFR on the overnight rate diminishes.

What Are the Effects of the ECB’s Negative Interest Rate Policy?

25 PE 662.922

But apart from this, what could the ECB do to avoid or overcome the reversal rate problem (if it were

to materialise)? The ECB has actually introduced an innovative tool in recent years: the TLTROs. This

new type of refinancing operation has attracted less attention than other unconventional tools, such

as QE or its negative DRF, but we believe it could actually help overcome the reversal rate issue. With

the launch of the TLTRO III in March 2019

11

, the ECB decided for the first time that the rate could be

negative and as low as the deposit facility rate (if some conditions were fulfilled in terms of lending

volume). In practice, this means that the banks resorting to TLTROs are paid to borrow from the ECB,

which partly compensates for the negative DFR on excess reserves.

At the start of the COVID-19 crisis, on 12 March 2020, the ECB went further and for the first time reduced

its TLTRO rate by 25 bps below the DFR, for banks fulfilling their lending benchmarks to the real

economy. On 30 April 2020, the ECB decided to further ease the conditions on its TLTROs by cutting

the applicable rate by a further 25 bps to as low as -1% (i.e. 50 bps below the DFR).

As discussed in Claeys (2020), making the level of the TLTRO rate independent from the DFR provides

a new way for the ECB to ease financing conditions. This allows the central bank to adopt a more

accommodative stance without having to cut its DFR further, thus avoiding its potential side effects.

Given that the rate is lower than what banks pay on their excess liquidity, this provides banks with a

strong incentive to borrow long-term from the ECB and to grant more loans. This, in turn, should

mechanically increase their reserve requirements, since these are calculated as a ratio of a bank’s

liabilities – mainly its customers’ deposits. Considering the new tiering system on reserve

remuneration, their exempted reserves would also be increased, even more than proportionally. This

ultimately should create a virtuous cycle for bank profitability and incentivise banks to lend to the

economy, despite negative policy rates (or more precisely thanks to a negative spread between the

DFR and the TLTRO rate). The main caveat is that the ECB will actually lose money on these operations.

However, this should not be a major source of concern, given that, as discussed in Chiacchio et al.

(2018), while it is preferable for the ECB to make profits rather than to record losses, it is not a profit-

maximising institution and its overriding mandate is price stability. As such, recording losses in the

short-to-medium term

12

when seeking to fulfil its macroeconomic function, should not stop the ECB

from using such a policy if it is effective.

If the ECB believes it is approaching the reversal rate but it needs to provide more monetary easing, it

should therefore refrain from cutting its DFR again, and instead reduce further its TLTRO rate below

its DFR.

Next, how to deal with potential financial stability issues? As discussed before, negative rates for a

too-long period, which could be necessary to fulfil the ECB’s price stability mandate, could nonetheless

lead to financial instability in the medium- to long-run. In our view, the best way to deal with financial

imbalances is to use macroprudential tools as the first line of defence. However, the euro area’s

macroprudential institutional framework might not be able of playing this crucial role, given its

decentralised nature and heterogenous functioning across European countries. It is therefore critical

to build a better set-up for the use of macroprudential tools in Europe to ensure that they can be used

forcefully and in a timely way when needed.

11

TLTROs I, which were the first refinancing operations conditional on new lending by the banks, were announced in June 2014. TLTROs II

were launched in March 2016.

12

Assuming that the negative spread of 50 basis points between the deposit rate and the TLTRO rate would in the end apply to a volume

of between €500 billion and €1 trillion in loans, this would lead to losses on these operations of between €2.5 and 5 billion, compared

with an average of €14 billion of distributable profits per year for the Eurosystem from 1999 to 2017 (Chiacchio et al, 2018).

IPOL | Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies

PE 662.922 26

Finally, at the current juncture, given the situation after one and a half years of the COVID-19 pandemic

and in 2020 the largest decline in GDP in the euro area since the Second World War, the ECB should be

extremely cautious and not rush before exiting unconventional monetary policies including

negative rates. Even if negative rates proved to be ineffective, or insufficient to bring the economy to

full employment, given the full pass-through between the deposit rate and market rates

13

, it would be

extremely dangerous to exit negative rates too soon as it could harm the post-COVID-19 recovery as

well as destabilise European sovereign debt markets. This would be highly damaging given the

increased role played by fiscal policy in terms of macroeconomic stabilisation.

13

This could be particularly relevant in particular if, as discussed above, the effects of interest rate changes are asymmetric and if the effects

of tightening are much stronger than the effects of rate cuts.

What Are the Effects of the ECB’s Negative Interest Rate Policy?

27 PE 662.922

REFERENCES

• Amzallag, A., Calza, A., Georgarakos, D. and Soucasaux Meneses e Sousa, J.M. (2019). “Monetary

Policy Transmission to Mortgages in a Negative Interest Rate Environment”, ECB Working Paper

2243. https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2243~a1f298ab9d.en.pdf

• Basten, C., and Mariathasan, M. (2018). “How Banks Respond to Negative Interest Rates: Evidence

from the Swiss Exemption Threshold”. CESifo Working Paper 6901, Munich.

• Bubeck, J., Maddaloni, A. and Peydró, J.-L. (2020). “Negative monetary policy rates and systemic

banks’ risk-taking: evidence from the euro area securities register”. ECB Working Paper Series No

2398 / April 2020

• Brunnermeier, M., and Koby, Y. (2018). “The Reversal Interest Rate”. NBER Working Paper No. 25406.

December 2018. https://www.nber.org/papers/w25406

• Chodorow-Reich, G. (2014). “Effects of unconventional monetary policy on financial institutions”,

Brookings Papers on Economic Activity (Spring), 155–204.

https://www.brookings.edu/wp-

content/uploads/2016/07/2014a_ChodorowReich.pdf

• Chiacchio, F., Claeys, G. and Papadia, F. (2018). “Should we care about central bank profits?”, Policy

Contribution 2018/13, Bruegel.

https://www.bruegel.org/2018/08/should-we-care-about-central-

bank-profits/

• Claeys, G. (2020). “The European Central Bank in the COVID-19 crisis: Whatever it takes, within its

mandate”, Study for the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs, Policy Department for

Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies, European Parliament, Luxembourg, 2020.

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2020/648811/IPOL_IDA(2020)648811_EN

.pdf

• Christensen, J.H.E. (2019). “Yield Curve Responses to Introducing Negative Policy Rates”, FRBSF

Economic Letter 2019–27, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco.

• Darvas Z. and Pichler, D. (2018). “Excess Liquidity and Bank Lending Risks in the Euro Area”, Study

for the Committee on Economic and Monetary Affairs, Policy Department for Economic, Scientific

and Quality of Life Policies, European Parliament, Luxembourg, 2018.

https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2018/626069/IPOL_STU(2018)626069_E

N.pdf

• ECB. (2018). “The cash holdings of monetary financial institutions in the euro area”, European

Central Bank, Economic Bulletin Issue 6/2018.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/economic-

bulletin/articles/2018/html/ecb.ebart201806_03.en.html

• Ferrari, M., Kearns, J. and Schrimpf, A. (2017). “Monetary policy’s rising FX impact in the era of ultra-

low rates”, BIS Working Paper, No 626. https://www.bis.org/publ/work626.pdf

• Geerolf, F. (2019). “A Theory of Demand Side Secular Stagnation”. Working Paper.

https://fgeerolf.com/hansen.pdf

• Guerrón-Quintana, P., and Kuester, K. (2019). “The dark side of low(er) interest rates”. Working

Paper. https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/files/4-Guerron-Quintana.pdf

• Hameed, A., and Rose, A. K. (2018). “Exchange Rate Behaviour With Negative Interest Rates: Some

Early Negative Observations”. Pacific Economic Review 23 (1): 27-42.

IPOL | Policy Department for Economic, Scientific and Quality of Life Policies

PE 662.922 28

• Heider, F., Saidi, F. and Schepens, G. (2019). “Life below Zero: Bank Lending under Negative Policy

Rates”, The Review of Financial Studies 32 (10): 3728–61.

• Holston, K., Laubach, T. and Williams, J. (2016). “Measuring the Natural Rate of Interest: International

Trends and Determinants”. Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, 2016-11, 43.

https://www.frbsf.org/economic-research/publications/working-papers/2016/11/

• Jobst, A., and Lin, H. (2016). “Negative Interest Rate Policy (NIRP): Implications for Monetary

Transmission and Bank Profitability in the Euro Area”. IMF Working Papers, 16(172), 48.

https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/wp/2016/wp16172.pdf

• Khayat, G. A. (2018). “The Impact of Setting Negative Policy Rates on Banking Flows and Exchange

Rates”. Economic Modelling 68: 1–10.

• Rostagno, M., Bindseil, U. Kamps, A., Lemke, W., Sugo, T. and Vlassopoulos, T. (2016). “Breaking

through the Zero Line: The ECB’s Negative Interest Rate Policy”, Presentation at Brookings

Institution, June 6.

https://www.brookings.edu/wp-

content/uploads/2016/05/20160606_Brookings_final_background-Compatibility-Mode.pdf

• Rostagno, M., Altavilla, C., Carboni, G. , Lemke, W., Motto, R. and Saint Guilhem, A. (2021).

“Combining negative rates, forward guidance and asset purchases: identification and impacts of

the ECB’s unconventional policies”, ECB Working Paper Series No 2564 / June 2021.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpwps/ecb.wp2564~e02f3aad4c.en.pdf

• Schnabel, I. (2020). “Going negative: the ECB’s experience”, Speech at the Roundtable on Monetary

Policy, Low Interest Rates and Risk Taking at the 35th Congress of the European Economic

Association, Frankfurt am Main, 26 August 2020.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2020/html/ecb.sp200826~77ce66626c.en.html

• Stansbury, A. and Summers, L. (2020). “The End of the Golden Age of Central Banking? Secular

stagnation is about more than the zero lower bound”, unpublished manuscript

• Stráský, J., and Hwang, H. (2019). “Negative interest rates in the euro area: Does it hurt banks?”,

OECD Economics Department Working Papers, 1574, 35.

https://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=ECO/WKP(2019)44&

docLanguage=En#:~:text=This%20conflation%20is%20confirmed%20by,of%20the%20ECB%20a

sset%20purchase

• Taylor, J.B. (1993). “Discretion versus policy rules in practice”, in Carnegie-Rochester conference

series on public policy, Vol. 39: 195-214, North-Holland.

https://web.stanford.edu/~johntayl/Onlinepaperscombinedbyyear/1993/Discretion_versus_Polic

y_Rules_in_Practice.pdf

• Woodford, M. (2003). Interest and Prices, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

PE 662.922

IP/A/ECON/2021-24

PDF ISBN 978-92-846-8184-6 | doi:10.2861/041324 | QA-09-21-214-EN-N

Several central banks, including the European Central Bank since 2014, have added negative policy

rates to their toolboxes after exhausting conventional easing measures. It is essential to understand

the effects on the economy of prolonged negative rates. This paper explores the potential effects

(and side effects) of negative rates in theory and examines the evidence to determine what these

effects have been in practice in the euro area.