Report

/

March 2021

Build Back Better Homes

How to Unlock America’s Single-Family Green Mortgage Market

Authors

Rita Ballesteros, Consultant

David Heslam, Earth Advantage

Greg Hopkins

Authors listed alphabetically. All authors from RMI unless otherwise noted.

Contacts

Greg Hopkins, ghopkins@rmi.org

Copyrights and Citation

Rita Ballesteros, David Heslam, and Greg Hopkins, Build Back Better Homes: How to Unlock

America’s Single-Family Green Mortgage Market, RMI, 2021,

http://www.rmi.org/insight/build-back-better-homes.

RMI values collaboration and aims to accelerate the energy transition through sharing

knowledge and insights. We therefore allow interested parties to reference, share, and cite our

work through the Creative Commons CC BY-SA 4.0 license. https://creativecommons.org/

licenses/by-sa/4.0/.

All images used are from iStock.com unless otherwise noted.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Madeline Salzman from the US Department of Energy for

technical feedback and non-policy content review throughout the development of this report.

The authors also thank the following individuals for offering their insights and perspectives

on this work:

Steve Baden, Residential Energy Services Network (RESNET)

Elizabeth Beardsley, U.S. Green Building Council

Alysson Blackwelder, U.S. Green Building Council

Jeremy Bourne, RiskSpan

Jacob Corvidae, RMI

Michelle Foster, Home Innovation

Ken Gear, Leading Builders of America

Jim Gray, Lincoln Institute of Land Policy

Janet Jozwik, RiskSpan

Cliff Majersik, Institute for Market Transformation (IMT)

Ryan Meres, Residential Energy Services Network (RESNET)

Robert Sahadi, Montgomery County Green Bank

Andrew Speake, National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL)

Clayton Traylor, Leading Builders of America

Signo Uddenberg, MKThink

Lowell Ungar, American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy (ACEEE)

This work was generously supported by Energy Foundation and the Ray & Tye

Noorda Foundation.

Authors & Acknowledgments

www.rmi.org

/

2Build Back Better Homes

About Us

About Earth Advantage

Earth Advantage is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization based in Portland, Oregon, that

addresses the environmental impacts of residential buildings by developing and promoting

green home standards, conveying green home data to the residential real estate market, and

supplying training to building professionals and a growing energy efficiency workforce.

About RMI

RMI is an independent nonprofit founded in 1982 that transforms global energy systems

through market-driven solutions to align with a 1.5°C future and secure a clean, prosperous,

zero-carbon future for all. We work in the world’s most critical geographies and engage

businesses, policymakers, communities, and NGOs to identify and scale energy system

interventions that will cut greenhouse gas emissions at least 50 percent by 2030. RMI has

offices in Basalt and Boulder, Colorado; New York City; Oakland, California; Washington, D.C.;

and Beijing.

www.rmi.org

/

3Build Back Better Homes

www.rmi.org

/

4Build Back Better Homes

Table of Contents

Executive Summary

Introduction

Background

Green Mortgages as a Scalable, Cross-Cutting Tool

Recommendations to Structure Single-Family Green

Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS)

Methods to Scale Single-Family Green Mortgages

Opportunities for Federal Policymakers

Conclusion

Appendices

Appendix A: Calculations and Assumptions

Appendix B: Proposed Calibration Framework for Green Mortgages

Appendix C: Existing Green Mortgage Origination Process Map

Appendix D: NREL Home Energy Cost Estimator Methodology

Appendix E: ResStock Representative State-Level Information

Appendix F: Additional Green Mortgage Product/Process Recommendations

Appendix G: Model Language for the GSEs’ 2022–2024 Duty to Serve Plans

Appendix H: Residential Green and Energy-Related Data Sources

Endnotes

5

7

10

16

19

24

29

32

35

56

36

39

43

44

49

50

51

54

Executive

Summary

www.rmi.org

/

6Build Back Better Homes

Executive Summary

The vast majority of America’s housing

stock is in need of improvements—not for

cosmetics, but for performance, health, and

safety. Over the next decade, shifts in utility

models, energy and climate policy, weather events,

and recognition of health and resilience priorities

will greatly expand this need. This is especially true

for low- to moderate-income (LMI) households and

communities of color. And yet, because the upfront

costs for these kinds of improvements largely fall on

homeowners, they are not likely to happen fast enough

without scalable low-cost financing solutions.

Concurrently, there is growing interest and demand

among capital markets investors for environmental,

social, and governance (ESG) investment options and

“green” securities. Financial institutions representing

over $18 trillion globally recently committed to align

their portfolios with the goals of the Paris Agreement,

1

but they lack sufficient market-ready green

investments to fully make this shift. The mortgage

industry is well positioned to help fill this gap.

Mortgages can become a primary investment vehicle

for deploying billions of dollars to meet this investor

demand while also fulfilling consumer demand for

green home improvements. Although the market

for multifamily green mortgage-backed securities

has grown tremendously (making Fannie Mae the

largest green bond issuer in the world for the fourth

consecutive year in 2020

2

), the single-family market

has only just begun to emerge as a destination for

green capital.

Innovations in housing data analysis, mortgage

processing and automation, and low-interest financing

products can facilitate this market transformation

through the existing real estate transaction process.

This report proposes practical solutions to reduce

friction in originating and securitizing single-

family green mortgage products already offered by

government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac (the “GSEs”) to create a new $2+ trillion

market within a decade. Specifically, this report offers:

•

A framework and qualification criteria for the GSEs

to structure single-family green mortgage-backed

securities. This would allow green mortgages for

retrofitting existing homes and for high-performing

new construction to be converted into a massive

new green bond market.

•

Methods for the GSEs and lenders to scale single-

family green mortgages. These include leveraging

green home data in underwriting and appraisal

processes to enable greater market efficiency

(targeting dedicated additional proceeds to higher-

opportunity homes and borrowers to pay for

improvements) and automating systems to reduce

existing burdens on lenders and appraisers.

•

Opportunities for federal regulators and

policymakers to support these goals, including

by ensuring information transparency to correct

major market failures and by climate-aligning GSE

lending activities.

As the primary engines in US housing finance,

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac offer the scale and the

mechanisms for market transformation. The GSEs

and other housing finance leaders can capitalize on

favorable market and policy trends and other key

windows of opportunity underway to position this

market for success.

Introduction

www.rmi.org

/

8Build Back Better Homes

The US housing market faces a dynamic set of

interrelated challenges: affordability, equity, health

and safety, and resilience, all in the face of an

increasingly urgent climate crisis. These challenges

disproportionately affect low- to moderate-income

(LMI) households and communities of color. Housing

market actors are not yet effectively directing

resources toward addressing these issues. However,

scaling readily available mortgage products can

help change that by increasing access to green

home improvements. This report recommends

targeted interventions to scale up single-family

green mortgage products offered by Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac through pathways that protect both

borrowers and lenders.

A robust single-family green mortgage market

can deliver significant benefits and investor-ready

environmental, social, and governance (ESG) impacts.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac could generate more

than $2 trillion of new green mortgage-backed

securities (MBS) within a decade by streamlining and

scaling up their existing green mortgage products to

comprise 15% of their annual single-family mortgage

volumes (half the penetration level achieved on the

multifamily side). This would improve nearly 9 million

homes across the country, generate net cost savings

of $12 billion for consumers, create roughly 650,000

domestic jobs, and avoid 57 million metric tons of

carbon emissions (see Appendix A for calculation and

assumption details).

3

Why Now?

Different market actors have attempted to scale

versions of green or energy-efficient mortgages in

the past, without much success at a national level.

In recent years, however, supply-side motivation and

consumer demand have become better aligned toward

common goals.

Capital markets have been seeing ESG demand from

investors continue to outpace supply, resulting in a

modest premium (or “greenium”) for green and ESG

investments like green bonds.

4

In the spring of 2020,

Fannie Mae launched its first single-family green MBS, in

part to meet such demand, sending a powerful market

signal. By the end of 2020, Fannie Mae had issued $111

million in these green bonds,

5

backed only by loans on

ENERGY STAR® Version 3.0 certified new construction

homes. However, this program can go further to include

pathways for millions of existing single-family homes to

benefit from green improvements.

Estimated 10-year impacts of scaling up single-family green mortgagesExhibit 1

Estimated 10-Year Impacts

$2.2 trillion 8.7 million $12 billion 650,000 57 million

Single-family green

mortgage-backed

securities market

Homes improved in

quality, performance, &

resilience nationwide

Net savings to

consumers, after higher

loan payments

Jobs created based on

consumer savings and

investment

Metric tons of

cumulative carbon

emissions avoided

www.rmi.org

/

9Build Back Better Homes

Streamlining mortgage financing for green home

upgrades will also support the efforts of many large

financial institutions (including some of America’s

top mortgage lenders) that have committed to

“climate-align” their portfolios with the goals of

the Paris Agreement through greener lending and

investment activities.

6

Additionally, there are now sophisticated, credible,

and readily available home energy data systems and

tools that can integrate into increasingly automated

mortgage underwriting and appraisal processes. The

GSEs have a timely opportunity to leverage these

tools and pursue tactical policy updates to streamline

single-family green mortgage adoption. The GSEs can

integrate these objectives into their upcoming Duty

to Serve plans (see Appendix G) and ensure that their

ongoing Uniform Appraisal Dataset (UAD) redesign

captures critical green data fields for all homes to

facilitate market development.

7

Now is the time to spur green products in the

mortgage market: historically low interest rates are

driving record high refinancing activity and can offer

attractive financing terms for green upgrades that

improve overall home quality and value. Finally, this

opportunity aligns well with key priorities of the new

Biden Administration to address inequities, housing,

and the climate crisis (including stated plans to

weatherize 2 million homes, retrofit 4 million buildings,

and build 1.5 million affordable new homes

8

), which can

be mutually tackled by unlocking a fair and data-driven

single-family green mortgage market.

Background

www.rmi.org

/

11Build Back Better Homes

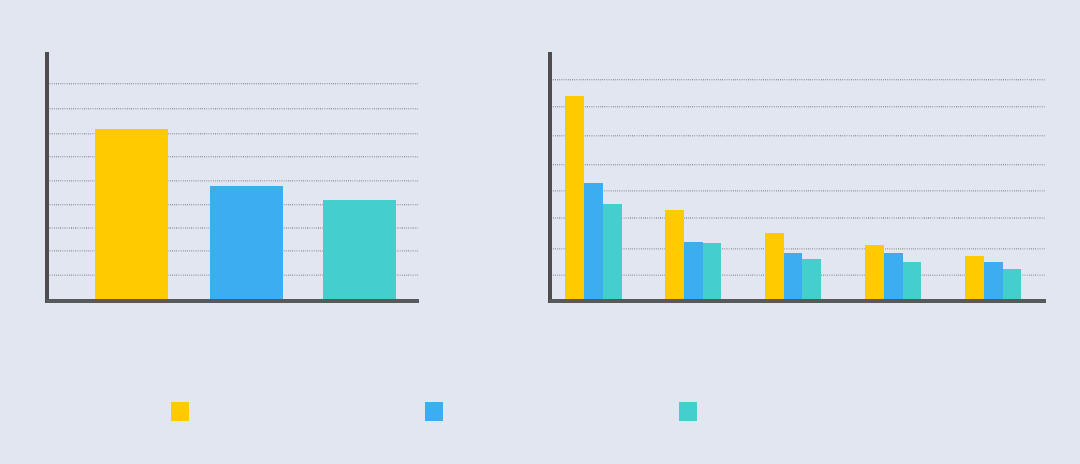

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Expenditure Survey 2019

Average expenditures as % of net income for the 80 million households earning <$70k/yearExhibit 2

Concurrent Housing Crises

When attempting to fundamentally shift how the

mortgage market works at scale, it is important to

fully understand the current market’s impacts and

ripple effects across the economy. The solutions

posed in this report will not solve every housing crisis

mentioned in this section. Rather, the aim of this

report is to propose solutions that can help and that,

at minimum, do not exacerbate these crises. The goal

of this section is to acknowledge the array of complex

and interrelated housing issues affecting homeowners

and residents today for consideration by the GSEs

and other mortgage industry leaders, as well as

policymakers, regulators, and program designers.

For most households in America, energy costs are

higher than either property taxes or home insurance

(as shown in the graphs below), yet these costs are

not systematically included in mortgage affordability

calculations.

9

Energy costs amount to significant

financial burdens for many Americans. Barriers to

funding and financing for cost-effective housing

improvements have led to persistent underinvestment

in housing infrastructure, resulting in too many

Americans living in substandard housing that is

expensive to operate. There are more than 98 million

single-family homes in the United States, roughly half

of which were built before building energy codes were

introduced over 40 years ago.

10

Poor energy performance is really a symptom of

larger housing crises concurrently impacting American

homeowners and renters. Today’s housing affordability

crisis, often concentrated in densely populated urban

areas, is due in large part to a lack of supply.

11

This

issue is especially pronounced in rental housing, where

in recent decades, the real income of renters has

not risen at the same rate as rental costs.

12

Although

housing prices have increased over time, asset quality

of existing homes has largely stalled or declined due to

aging features and typical wear and tear.

7.1%

4.8%

4.2%

9%

8%

7%

6%

5%

4%

3%

2%

1%

16%

14%

12%

10%

8%

6%

4%

2%

Energy

Costs

Energy Costs Property Taxes Insurance & Maintenance

Income Band:

Households:

Property

Taxes

<$15k

7M (13%)

$15k–$30k

22M (17%)

$30k–$40k

13M (10%)

$40k–$50k

11M (8%)

$50k–$70k

17M (13%)

Insurance &

Maintenance

www.rmi.org

/

12Build Back Better Homes

This creates situations where both a home’s upfront

costs and maintenance costs rise, compounding the

cost pressure on home buyers and renters.

13

In addition,

inefficient homes are not only more expensive to

operate, but on average also have worse indoor air

quality that can increase occupants’ healthcare costs.

Without convenient and affordable capital investments,

these properties face higher risks in terms of energy

costs, health threats, and loan performance.

Increasingly frequent extreme weather events

pose additional risks. Older homes with deferred

maintenance may be more susceptible to significant

damage from high winds, heavy rainstorms, smoke

from wildfires, and extreme temperatures during

heat waves and cold snaps. According to the National

Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA),

2020 was the sixth consecutive year with ten or more

billion-dollar weather and climate disaster events in

the United States.

14

In 2020 alone these disasters

caused $95 billion in damage nationwide, almost

doubling the damage in 2019.

15

As a result, insurance

costs to cover damages have been increasing or

becoming entirely unavailable to some homes.

16

A recent report commissioned by the Commodity

Futures Trading Commission issued stark warnings

about the impacts of climate change on financial

markets for these same reasons.

17

Fortunately, the

most exhaustive cost-benefit analysis of natural

hazard mitigation to date found that every $1 invested

in home retrofits to protect against floods and

hurricanes can save $6 (every $1 invested in retrofits

to protect against fires and earthquakes can save $2

and $13 respectively).

18

These housing risks disproportionately impact

lower-income households and households of color.

Nearly 31 million US households face high energy

burdens (i.e., spend more than 6% of their income

on utility bills, roughly double the national average).

And a staggering 16 million US households face

severe energy burdens (i.e., spend more than 10% of

their income on energy).

19

Approximately 25 million

households have reported foregoing necessities like

food or medicine to pay their energy bills (7 million of

which face that decision on a monthly basis).

20

High energy burdens can also lead households to

dangerous situations, such as using ovens for heat or

risking unsafe indoor temperatures. These burdens are

particularly concentrated in communities of color: the

median energy burden for Black households is 43%

higher, and for Hispanic households 20% higher, than

for non-Hispanic White households.

21

There has been a long history of racist housing and

lending policies and practices (including but not

limited to: New Deal enforced segregation, redlining,

restrictive covenants, biased appraisals, and real

estate agent steering). This has resulted in households

of color disproportionately making up lower-income

households and occupying lower quality housing

in the United States.

22

Intergenerational wealth is

often generated in families through homeownership

(and the financial security that assets can provide).

Thus, strategies that can upgrade existing housing

and reduce the costs of, while increasing access to,

homeownership can be particularly beneficial for

households that have been precluded from such wealth

accrual opportunities.

It has been found that the median White household has

nearly 20 times more wealth than the median Black

household.

23

And although 73% of White households

own their home, only 41% of Black households

do.

24

Additionally, communities of color are more

geographically concentrated in regions where land

prices have been increasing rapidly, contributing

to displacement as property taxes rise. These

communities are also often more exposed to, and

harder hit by, the fallout from natural disasters and

extreme weather, and are more likely to live close to

power plants and high-pollution areas.

25

This leads to

higher rates of health complications and particularly

asthma, which affects Black children at more than

double the rate of White children (16% versus 7%).

26

Meanwhile, the backdrop behind all these challenges

is an increasingly urgent climate crisis. The scientific

consensus is clear: to avoid the catastrophic effects of

climate change, we must limit global temperature rise

to 1.5°C, which will require a 50% reduction in global

emissions by 2030 compared with 2010 and net-zero

global emissions by 2050.

27

www.rmi.org

/

13Build Back Better Homes

Household energy use accounts for roughly 20% of

all US greenhouse gas emissions. However, our homes

represent a critical segment of the economy that is

not decarbonizing at nearly the rate required.

28

A lack

of information transparency and awareness, market

signals and incentives, and scalable low-cost financing

solutions all contribute to stagnant residential sector

progress on climate and equity issues. Failure to

change this trajectory will mean substantial risk

to both the housing stock and the mortgage and

insurance industries in the years ahead.

Single-Family Market Context

Together, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac back nearly half

of all single-family mortgage originations, to the tune

of approximately $1 trillion per year.

29

The GSEs are

federally backed home mortgage companies that buy

single-family and multifamily mortgages originated by

lenders across the country, guarantee their principal

and interest payments, and then repackage and sell

them as mortgage-backed securities (MBS) on the

secondary market. This makes the mortgage market

more liquid, stable, and affordable. To that end, they

also standardize requirements to which lenders and

appraisers nationwide conform.

Between 2009 and 2019, annual mortgage origination

volume averaged $1.8 trillion for one- to four-unit

residential buildings, split roughly equally between

refinance and purchase products.

30

Yet only a tiny

fraction of this volume prioritized getting families into

homes with low energy costs or improving the housing

stock. In 2018, only 3% of the total mortgage loan

volume was in home improvement financing products,

and limited data suggests only a small portion of these

are dedicated to green home improvements.

31

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac both offer green

mortgage products that finance energy (and other

green) improvements, but neither have been

effectively adopted by lenders at scale to allow

widespread access. Furthermore, neither GSE has yet

identified a full framework for green improvement

financing of existing homes to be included in single-

family green MBS; Fannie Mae’s new single-family

green MBS program currently only covers ENERGY

STAR certified new construction homes.

Although the percentages of mortgage loan volume

including home improvement costs so far are

small, the total potential for financing green home

improvements is compelling. To put this market in

context, the total annual budget of the Weatherization

Assistance Program (WAP)—the US government’s

energy improvement assistance program for low-

income families—is $1.1 billion, less than 2% of the

annual volume of home improvement mortgage loans.

i

Adding in the total annual amount spent on residential

energy efficiency through all utility-funded programs

nationwide, this volume of annual spending is still only

about 6% of the existing home improvement mortgage

loan market size, or only 0.18% of the total annual

mortgage market by volume.

ii

Unlocking even a fraction of the existing single-family

mortgage market to enable streamlined access to low-

interest financing for green improvements will help

millions more residents access the benefits of higher-

performing homes. Given the significant potential for

cost-effective green home upgrades, a substantial

portion of the GSEs’ single-family mortgage issuance

could become green within 10 years.

Today, homeowners are spending money on home

improvements, but typically need to seek out

upgrade packages, financing, and products on

their own. According to Harvard’s Joint Center for

Housing Studies report, Improving America’s Housing

2019, US homeowners spent $68 billion in 2017 on

improvements to roofing, siding, windows, doors,

HVAC systems, and insulation—all projects that could

generate meaningful home energy savings if more

i

2018 home improvement loans were $60 billion; WAP in FY18 totaled $1.1 billion ($250M from DOE, $453M from LIHEAP, $407M from

nonfederal sources).

ii

Utility energy efficiency program spending on residential programs was slightly under $3 billion in 2018:

https://www.eia.gov/todayinenergy/detail.php?id=42975

www.rmi.org

/

14Build Back Better Homes

efficient options are installed. Such systems and

equipment replacements were the fastest growing

segment of the home improvement market in recent

years (see pie charts below).

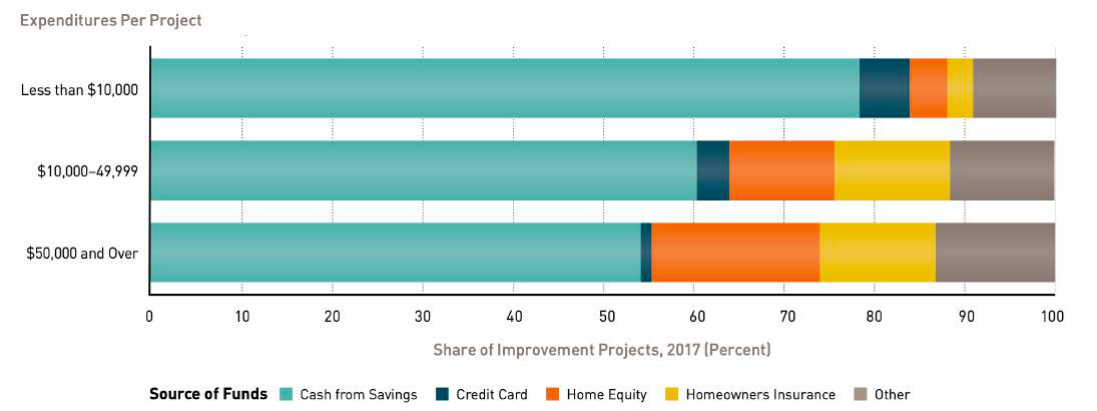

Notably, US homeowners used cash from savings to

pay for 77% of home improvement projects, with

the next largest sources being credit cards or retail

store charge cards. This paradigm disproportionately

excludes lower-income households that do not have

the savings or credit to pay for these upgrades.

The report concludes that the share of replacement

projects is likely to remain high in the coming

decade as the housing stock ages, and that offering

homeowners additional financing options (in lieu of

cash savings) would likely lead to significantly stronger

growth in improvement expenditures.

32

Replacement projects take up a growing share of homeowner improvement budgets Exhibit 3

Notes: Replacements include exterior, systems and equipment, and interior projects. Discretionary projects include kitchen and bath remodels,

room additions, and outside attachments. See Table A-1 in Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies report, Improving America’s Housing 2019,

for more detailed definitions of project categories. Homeowner improvement spending totaled $220 billion in 2007 and $233 billion in 2017.

Source: Improving America’s Housing 2019, Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University.

www.rmi.org

/

15Build Back Better Homes

Most homeowners rely on cash from savings to finance improvementsExhibit 4

In addition to replacements, national surveys show

that consumers want energy efficiency in their homes

but the market is not yet meeting that demand.

In a Demand Institute survey of more than 10,000

households, increased energy efficiency was the

number one housing desire, ranked according to the

size of the “satisfaction gap.” In other words, 71% of

respondents thought energy efficiency is important

but only 35% were satisfied with their current home.

Increased energy efficiency was ranked higher than

updated kitchens and finishes, safe streets, privacy,

and more.

33

Key findings from the National Association of

REALTORS’ latest annual survey of its members

include that: 70% of agents and brokers reported

that energy efficiency promotion in listings is valuable

and 61% found that consumers are interested

in sustainability. Yet 61% were not confident

connecting clients with green lenders, and the highest

ranked market issue (from a list of 13 issues) is

“understanding lending options for energy upgrades

or solar installations.”

34

Notes: Credit Card category includes retail store charge cards. Home Equity includes cash from refinancing, home equity loans, and home

equity lines of credit. Other includes contractor-arranged financing and all other funding sources, including those not reported.

Source: Improving America’s Housing 2019, Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University.

Green Mortgages as

a Scalable, Cross-

Cutting Tool

www.rmi.org

/

17Build Back Better Homes

These trends point to a compelling opportunity for

green mortgages to overtake a substantial market

share in the years ahead, if the delivery process

can be sufficiently streamlined and scaled. A viable

solution requires the right mortgage products and

the right processes to make delivering those products

easy, targeted, and scalable. The right products

are largely in place now, but process improvements

are still needed so that these products can become

standard offerings to borrowers. The following

sections of this report discuss how to better activate

the market for deployment.

Fannie Mae’s HomeStyle® Energy mortgage and

Freddie Mac’s GreenCHOICE® mortgage allow

borrowers to use mortgage proceeds to finance the

cost of green single-family home improvements

when purchasing or refinancing a home, up to 15%

of its “as-completed” value. Eligible improvements

within their “green” scope include energy efficiency

measures (e.g., air sealing, insulation, high-efficiency

windows and HVAC equipment), water efficiency

measures (e.g., low-flow fixtures), renewable energy

(e.g., solar panels), and also resilience improvements

(e.g., hazardous brush and tree removal in fire zones,

storm surge barriers and retaining walls, foundation

retrofitting for earthquakes).

They also permit homeowners to finance certain pre-

existing debt related to green improvements (e.g.,

from residential PACE,

iii

utility efficiency programs,

consumer loans), rolling those pre-spent dollars into the

new mortgage. This takeout mechanism can enable the

GSEs to play a role in providing liquidity for other green

home financing providers in the marketplace. This can

free up more capital for those actors to redeploy within

their programs while affording borrowers the lower

interest rates of a mortgage product.

These types of green home improvements are not

a comprehensive solution for all the housing crises

described above. However, when well-implemented,

they can meaningfully improve affordability and health

and safety outcomes for borrowing households, while

also reducing loan performance risk and climate risk

at scale. Given the housing and energy burdens that

iii

Property-assessed clean energy, a loan product financed through the property’s tax assessment.

www.rmi.org

/

18Build Back Better Homes

LMI households and households of color often face,

these groups can benefit significantly from well-

designed and consumer-protected financing products.

At current historically low interest rates, mortgage

products offer what may be the most affordable

financing available for such projects. When offered

through standard real estate transaction and refinance

processes, these mortgage products can scale to

impact millions of homes each year.

Appendix A includes an example of project-level

financial benefits for households that finance energy-

and/or water-saving green home improvements

through green mortgages at a basic level (15%

savings) and deeper level (25% savings). In practice

these figures will vary depending on the measures

and technologies installed. A household could

realize average annual net savings (i.e., utility cost

savings offset by slightly higher mortgage payments,

assuming the full project size is added to the mortgage

balance) of $314 after a basic retrofit and $326 after a

deeper retrofit based on the assumptions in Appendix

A. The GSEs and/or lenders can set up automated

checks to confirm that expected net savings are

estimated to be positive for borrowers upfront to

better protect consumers. Note that these examples

do not take into account other potential value streams,

such as reduced health and safety costs or increased

home value.

Green homes offer more than just utility cost

savings. Residents also benefit from improved

comfort and indoor air quality, increased resilience

to environmental disasters, and reduced carbon

emissions.

35

Green homes also have the potential

to experience reduced loan default rates: one study

covering a time period that included the Great

Recession found 32% lower default rates for energy-

efficient homes than non-energy-efficient homes.

36

Freddie Mac’s own analysis found that RESNET’s

Home Energy Rating System (HERS) rated homes sold

for 2.7% more than comparable unrated homes, and

that better-rated homes sold for 3%–5% more than

lesser-rated homes. Additionally, the study showed

that loans with high debt-to-income ratios (45% or

above) with ratings appear to have lower delinquency

rates than unrated homes.

37

A separate meta-analysis

of dozens of valuation studies found a 4.3% value

premium for certified green homes.

38

Given that

appraisal standards do not yet explicitly account for

home performance, this premium is likely based on

perception and may be understated.

Recommendations

to Structure Single-

Family Green

Mortgage-Backed

Securities (MBS)

www.rmi.org

/

20Build Back Better Homes

The ability to pool and securitize a sufficient volume of

eligible mortgages that can be sold in the secondary

market as green MBS is key to keeping capital flowing

to finance green homes and improvements. This value

chain can generate mutually reinforcing benefits

for the GSEs, lenders, and borrowers. Studies have

found that capital markets investors pay a premium

for green bonds, particularly for those that are

government issued and investment grade, and that

follow defined governance and reporting procedures.

For example, an average “greenium” up to 9 basis

points has been observed on the secondary market.

39

The additional cash flow stream from such premiums

can benefit market participants in different ways,

depending on the type of securitization. In the case of

lender swap transactions (the most common type), this

can be a significant incentive for lenders and, in turn,

can enable lenders to offer discounted interest rates

to borrowers of green mortgages, bolstering demand.

In the case of portfolio securitization transactions, this

can be a significant incentive for the GSEs themselves,

which could be partially passed on to the benefit of

lenders and/or borrowers of green mortgages.

40

The GSEs’ single-family green MBS business can take

lessons learned from their successful multifamily

counterparts, which began issuing green MBS in 2012

and grew substantially—likely in part thanks to the

use of incentives. Although it took five years for the

multifamily market to achieve multibillion dollar scale,

existing performance standards and access to data

in the single-family market means there does not

need to be such a long period for a robust and viable

single-family green MBS market. Although single-

family loan sizes are inherently smaller and more

fragmented with more participants, adding complexity

to the securitization process relative to the multifamily

business, this can also offer advantages for investors

in terms of risk diversification across MBS pools.

As mentioned above, the securitization of single-

family green MBS started in 2020 with Fannie Mae’s

new program. At time of writing, that program only

uses one method to identify properties for inclusion:

the EPA’s ENERGY STAR Certified Homes program

for new construction. Expanding the single-family

green MBS market to include homes that are already

green, as well as homes that can access financing to

become green, is necessary for equitable distribution

of benefits and achieving scale. This report proposes a

framework and qualification criteria to that end.

www.rmi.org

/

21Build Back Better Homes

Multifamily Green MBS Context

Fannie Mae offered its first multifamily green

mortgage loans in 2011 and issued its first

multifamily green MBS in 2012. These were initially

based on multifamily new construction projects.

In 2014, Fannie Mae and the EPA announced the

ENERGY STAR Score for multifamily buildings,

creating a consistent method to measure

performance of existing multifamily buildings.

In 2018, Fannie Mae established a Green Bond

Framework. By the end of 2020, Fannie Mae had

issued over $85 billion in multifamily green bonds,

making it the world’s largest green bond issuer

for four straight years.

41

On average over those

four years, Fannie Mae’s multifamily green MBS

represented over 30% of its total multifamily

mortgage volume.

42

Although Freddie Mac started

this effort after Fannie Mae, its multifamily green

business has also been growing. It has purchased

$63 billion in multifamily green mortgages since

2016 and issued over $3 billion in multifamily green

MBS since 2019. In the multifamily market, the

large majority of green MBS volume has been for

green improvements to existing buildings, primarily

through Fannie Mae’s Green Rewards program.

Fannie Mae’s cumulative green MBS issuanceExhibit 5

Source: Fannie Mae Capital Markets, “Multifamily Green MBS," 2021; excludes retired Fannie Mae green programs.

$90,000M

$80,000M

$70,000M

$60,000M

$50,000M

$40,000M

$30,000M

$20,000M

$10,000M

Single-Family (ENERGY STAR Certified

Construction)

Multifamily Green Building Certification Multifamily Green Rewards

2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020

$72B

$13B

$111M

www.rmi.org

/

22Build Back Better Homes

Methods to Scale Single-Family

Green MBS

Given the needs of much of the single-family

housing stock, there is a significantly larger market

opportunity for single-family green mortgages. Single-

family green MBS achieving market penetration of

15% of total GSE single-family mortgage volumes (half

the level achieved by Fannie Mae’s multifamily green

business) would equate to over $150 billion per year

as shown in Appendix A, with most of that financing

existing homes.

The single-family green MBS market can expand

into both new and existing homes simultaneously by

continuing to identify and securitize more new green

homes, and by developing a framework to identify

and categorize green improvements for existing

homes. The discussion below provides a summary of

this proposal, which follows the logic of Fannie Mae’s

Multifamily Green Bond Framework. Further details

can be found in Appendix B, along with a discussion

of the importance of leveraging rating systems in

addition to certification programs.

Single-family green mortgages can be categorized for

three types of homes: new construction that meets

varying levels of above-code criteria, comprehensively

retrofitted existing homes, and existing homes

that have had basic (yet impactful) upgrades. We

propose a framework to establish these qualifications

for evaluation into green MBS with five tiers of

related performance and impact (details on specific

certifications, ratings, and other criteria are included

in Appendix B).

Existing homes that undergo improvements should

achieve a rating or certification with appropriate

designation based on the level of savings or impact.

This framework can be used to give green designations

to homes with mortgages that finance energy- or

water-saving improvements with independent third-

Methods to measure required achievement for single-family green mortgage tiersExhibit 6

Qualifying Home

Types

Towards Zero Group 1:

High

Performance +

Ventilation

Group 2:

High Efficiency

Group 3:

Base

Certifications/

Ratings

Group 4

Basic

Retrofits

High-Performance

New Construction

Homes

Via Certification Via Certification Via Certification

or Rating*

Via Certification

or Rating*

N/A

Comprehensive

Retrofits and/or

Solar

Via Certification Via Certification Via Certification

or Rating*

Via Certification

or Rating*

N/A

Basic Retrofits

and/or Solar

N/A N/A Via Rating Via Rating Via Rating

* Note on certifications versus ratings: green home certifications such as LEED, ENERGY STAR, and Passive House establish that a home

has achieved a target level of high performance and/or met other criteria. Home energy ratings such as HERS and Home Energy Score can

assess any home’s assets (equipment, envelope, etc.) and model energy consumption, assigning a score and recommending cost-effective

improvements that save energy and money. At a practical level, ratings can be more easily leveraged to gauge retrofit impacts while more

comprehensive certifications will typically apply to higher tiers.

www.rmi.org

/

23Build Back Better Homes

party verified or modeled savings of at least 15% on

a whole-home basis, measured against the home’s

current performance. This 15% savings threshold is

based on the GSEs’ multifamily green criteria and

aligns with existing Duty to Serve criteria for single-

family green mortgages.

In cases where the green mortgage allows for basic

improvements without an energy report (currently

up to $6,500 for Freddie Mac or $3,500 for Fannie

Mae—which we recommend increasing to at least

$5,000), those basic improvements should be chosen

from prequalified lists of cost-effective measures

that have been determined to reliably deliver cost-

effective savings. Such eligible measure lists can be

curated, short, easily verifiable (as better than existing

conditions), and reevaluated annually based on

studies of a sampling of homes to verify that expected

savings are being realized. For reference, the DOE’s

Weatherization Assistance Program achieves average

energy cost savings of 13% with basic measure

packages that cost on average $4,695 per home.

43

The expansion of multifamily green MBS to handle

existing buildings required the development of a rating

system for existing multifamily buildings. In the single-

family market there are already two energy rating

systems in use nationally: HERS® and Home Energy

Score™. These programs deliver energy reports (each

with a score or rating of the home’s current condition)

that can be used to qualify improvements financed

by the GSEs’ green mortgage products. The scores

produced from these two rating systems can also be

used on their own to categorize loans into the lower

tiers of the proposed single-family green mortgage

designation framework.

As part of the final certification of completion

process, the GSEs could require that lenders have

qualified third parties inspect each completed

project and provide a final rating. This step will

ensure the work is verified by an energy professional,

protecting consumers and mitigating the risk of

fraud. Additionally, a “test out” score can be used

to determine relative performance and inform green

MBS disclosures and tracking. The large and growing

number of trained green raters nationwide can supply

updated score reports through established business

models. A benefit of requiring a rating after work is

completed is that some homes may qualify for higher

green tiers, which could offer lower interest rates for

those borrowers. Another benefit is that the rating will

generate a verified energy cost estimate, which can

facilitate an automated valuation adjustment of the

property based on its relative energy performance.

A critical component of updated processes is to

capture green mortgage loan designations in loan

delivery data. The GSEs use the Uniform Loan Delivery

Dataset (ULDD),

44

an aligned format for lenders to

communicate details about each mortgage loan sold.

The ULDD informs the key characteristics needed by

the GSEs in order to pool and securitize loans into

MBS. Several green home databases now exist that

document third-party home certifications and ratings

(see Appendix H for more detail). The automated

integration of such data can enable lenders and the

GSEs to identify both qualifying green properties

that are already in their portfolios and new green

properties as loans are acquired.

The GSEs’ next update of the ULDD should include the

necessary data fields for green mortgage loans. In

the interim, an industry working group can be formed

to recommend how existing green home data sources

(including those recommended in this report) can be

leveraged for this purpose.

Methods to

Scale Single-

Family Green

Mortgages

www.rmi.org

/

25Build Back Better Homes

Before the single-family green MBS market can

reach its potential, single-family green mortgage

processes must be improved. Adoption of the GSEs’

existing single-family green mortgage products

remains extremely low to date because of a lack of

awareness and demand from consumers and specific

operational pain points that add complexity, time,

and cost for lenders.

The GSEs provide favorable terms for lenders, giving

a $500 credit per loan for green mortgage origination

and allowing lenders to close and deliver these

loans without recourse before the improvements

are completed. There is no rate premium for green

mortgages, and they can be bundled with other GSE

products (e.g., low down payment mortgages) that

further improve affordability and access to capital.

But along with these perks come additional process

steps and considerations that have made them more

challenging than conventional mortgage originations.

For reference, Appendix C includes a high-level

diagram illustrating the single-family green mortgage

origination workflow based on existing GSE guidelines

for lenders.

Single-family green mortgage products will inevitably

involve some level of additional process steps

compared with a standard mortgage. However, these

need not be obstacles because innovations in housing

data analysis and automation can be leveraged.

Below are the top three operational pain points that

can be addressed in the immediate term (additional

recommendations can be found in Appendix F):

Lack of awareness/demand and inability to

effectively sell green mortgage products

Burdensome project evaluations for lenders

Limited market of green appraisers and lack of

comps for as-completed valuations

Data and automated solutions available today, in

combination with updates to GSE policies and lender

guidelines, can help overcome these process barriers

to scale up adoption. Below are brief descriptions of

these significant but surmountable lender process

pain points, followed by recommendations for the

GSEs, FHFA, and market-leading lenders to consider

as part of broader efforts to unlock the single-family

green mortgage market:

Lack of awareness/demand and inability to

effectively sell green mortgage products:

Home energy information has been largely

invisible to most homeowners and residents,

except for a handful of jurisdictions in the United

States with residential energy disclosure policies.

Without access to this information, lenders

have been unable to account for energy costs in

mortgage underwriting and appraisal standards,

leaving them no way to identify borrowers and

homes that can meaningfully benefit from green

home improvements through green mortgages.

Because of these information barriers, both

lenders and borrowers miss opportunities to

pursue green mortgage products.

Leverage home energy cost data to increase

visibility of home performance and drive

demand: Data exists today—high-quality,

nationally standardized data from trusted

sources such as the US Department of Energy

(DOE)—that can be leveraged to auto-populate

home energy cost estimates and other

performance metrics into the underwriting

process. This data can enable lenders to initiate

conversations about green mortgage products

with borrowers and more effectively target

homes that may be costly to operate. Adding

a data field for “home energy cost estimate”

(ECE) through the GSEs’ ongoing Uniform

Appraisal Dataset (UAD) redesign initiative

www.rmi.org

/

26Build Back Better Homes

can effectively capture this information for all

homes nationwide.

Existing tools and databases can allow lenders

to capture ECEs from home ratings (e.g., HERS

or Home Energy Score) and green certifications

when they are available, or capture a baseline

ECE for the majority of homes with no third-

party rating. This same data field can be

leveraged in two use cases: by lenders to better

target and sell green mortgage products,

and by automated valuation models (AVMs)

and appraisers as a baseline for calculating

appraised value adjustments.

The DOE’s National Renewable Energy

Laboratory (NREL) recently developed a Home

Energy Cost Estimator tool to generate home-

specific energy cost estimates for this context

and use case, presenting an automated solution

aligned with the use of automated underwriting

systems and AVMs. This tool is built on

ResStock™, NREL’s comprehensive database

of national housing stock characteristics that

leverages advanced energy modeling and high-

performance computing.

The data is post-processed via six common

appraisal fields: home size, age, location,

utilities, cooling type, and foundation type.

This tool could be integrated with the GSEs’

automated underwriting software (Fannie Mae’s

Desktop Underwriter® and Freddie Mac’s Loan

Product Advisor®) as an additional third-party

vendor, similar to how credit scores are imported

from external sources. This would introduce

a key data point that can jumpstart the green

mortgage origination process. For more detail on

the NREL tool and its methodology, please see

Appendix D.

Burdensome project evaluations for lenders:

Currently, lenders must verify the eligibility

and cost-effectiveness of itemized energy

technologies for green mortgage products

(including to receive credit under Duty to

Serve). However, lenders lack the expertise in

energy technologies and building science to

conduct this work confidently. Due to a lack of

underwriting system integration, this typically

also involves manual calculations outside of

largely automated loan origination processes,

adding complexity, time, cost, and confusion to

the process for lenders.

Leverage eligible measure lists to simplify and

streamline project evaluations for lenders:

State- or region-specific eligible measure lists for

cost-effective measures can be used to streamline

eligibility and cost-effectiveness determinations

for lenders. This concept is permitted by FHFA’s

Duty to Serve regulation,

45

but it is not being

used in practice.

At minimum, the GSEs’ seller

guidelines should be updated to permit the use of

such lists. ResStock has data that could be used to

create lists for this purpose,

46

and further analysis

could allow for prequalified eligible measure lists

at a state or regional level for use by lenders.

Additional resources like state- and utility-led

residential efficiency programs can be leveraged

to establish regionalized eligible measure

lists for upgrades that will most reliably

deliver energy and cost savings to homes,

with added potential to align with state policy

goals. These lists can be curated and updated

annually based on independent verifications

of a sampling of homes to ensure that savings

estimates maintain accuracy over time. For

a representation of ResStock’s state-level

information, see Appendix E.

www.rmi.org

/

27Build Back Better Homes

Limited market of green appraisers and lack of

comps for as-completed valuations:

The GSEs’ current green mortgage products

require appraisers to determine the home’s as-

completed value (i.e., after the improvements

are made) for every project before the financing

has been approved. This adds time and cost

to the process and presents a challenge for

appraisers to attest to market reaction to green

features that have not yet been installed. Today,

only a small subset of appraisers are trained to

perform green appraisals, and these appraisers

do not have access to widespread comps for

green features. Again, the green mortgage

market is stymied because standard processes

do not capture the necessary data.

Leverage automation to simplify and streamline

as-completed valuations:

The GSEs can mitigate the as-completed appraisal

challenge by recognizing the value added by

efficiency improvements using automated

methods based on the income valuation approach.

Automating this step in the process, for example

via the GSEs’ automated appraisal tools, will

remove a significant barrier to help jumpstart the

market for green mortgages. With available data

like home energy cost estimates and the use of

prequalified measure lists for basic improvements

as described above, the opportunity exists to

change the system of valuation into one of

evaluation (i.e., AVM-based value adjustments

confirmed by human appraisers) rather than full

manual appraisals in all cases.

This approach also helps protect consumers by

requiring the energy savings to be higher than

the cost of improvements, thus creating positive

cash flow for the borrower. If no efficiency-

related improvements are made, then there

is no attribution of value, mitigating the risk

of devaluing homes and/or limiting access to

credit. Basic improvements should only require

automated evaluations, which can open up the

market to borrowers that need smaller—but still

valuable—energy upgrades. More comprehensive

retrofits will still benefit from the analysis that

comes with full as-completed appraisals.

Additional recommendations to address other

operational challenges are detailed in Appendix

F. Given the needs of the US housing market, we

also recommend expanding the scope of the GSEs’

single-family green mortgage program to include the

following activities:

•

Expand eligible measures to further improve

health and safety outcomes: The pandemic

has shined new light on the importance of

healthy indoor air quality. There are increasingly

understood and well-documented risks to

respiratory health from combustion-based

appliances in homes, which release toxic pollutants

that can increase indoor air pollution to levels

that would be illegal outdoors.

47

Related health

risks exacerbated by poor housing infrastructure

are also gaining attention from policymakers and

consumers. These health risks disproportionately

affect lower-income households, and especially

children. Therefore, green mortgage products

should also be able to finance home electrification

upgrades and other health improvements.

Replacing combustion-based appliances and

equipment with cost-effective, clean electric

alternatives (e.g., heat pumps, heat pump water

heaters, induction stoves) can not only improve

health, it can also save money. And it is a critical

part of meeting climate targets—decarbonizing

the economy requires solutions for the 70 million

homes and buildings that burn fossil fuels on-site.

48

•

Develop plans to increase access, affordability,

and consumer protection for communities of

color: The mortgage industry has an opportunity

to improve racial equity and ensure communities

of color can access the benefits of higher-

performance homes through green mortgages.

These products can be used to help correct some

of the racial inequities historically driven by the

mortgage industry, such as disparate housing

quality and energy burdens.

For example, the GSEs can develop plans and

partner with lenders and community organizations

to more effectively deliver green mortgages in

the highest energy-burdened zip codes of the

www.rmi.org

/

28Build Back Better Homes

United States. These mortages can finance green

improvements for low-performance homes that

have lacked access to capital in the past. This could

be integrated into efforts to support first-time

homeownership in these communities, including

by educating consumers about green mortgage

products in combination with other GSE affordable

lending products and down payment assistance.

As use of AVMs continues to grow in the mortgage

industry, the GSEs should also take steps to assess

impacts in majority-Black neighborhoods. New

research has shown that AVMs can produce larger

errors in these neighborhoods that may reinforce

the impacts of past racial discrimination.

49

FHFA and the GSEs should work with counseling

agencies, community organizations, industry

experts, and other stakeholders to develop

actionable plans designed to meet the needs of

these underserved communities.

These solutions can be tested by the GSEs, market-

leading lenders, and other partners through pilot

projects to track and quantify the impacts. Pilot

projects and ambitious green mortgage targets can be

incorporated into the GSEs’ next Duty to Serve plans

for the period 2022–2024, as proposed in Appendix

G, and/or developed outside of Duty to Serve. Better

designed processes through automated and data-

driven solutions means these efforts can scale with

only limited training and education needs for lenders

and appraisers.

Various consumer protection measures are key to

delivering benefits to both borrowers and lenders.

Consumer protection measures include activities

like automated checks to confirm positive net

savings expectations for borrowers, curated cost-

effective eligible measure lists, qualified contractor

networks, post-completion independent third-party

verification ratings, and quality control systems

that include follow-up evaluations for a sampling of

completed projects to verify savings. The GSEs can

work with industry experts, consumer advocates,

and other key stakeholder groups to ensure that

consumer protections are sufficiently incorporated

into efforts to scale up this market. Ultimately, the

GSEs must ensure that financed home performance

improvements actually translate into increased

asset value for homeowners. This work can redirect

consumer spending away from utility bills and toward

their own home’s value.

Opportunities

for Federal

Policymakers

www.rmi.org

/

30Build Back Better Homes

The federal government can also take action to better

align housing finance with its economic, equity, and

climate goals, including by scaling up the single-family

green mortgage market. There are many reasons

to take on this effort: to improve the US housing

stock, correct market failures, protect consumers,

address inequities, and create durable green home

retrofit jobs at scale. Since the New Deal, the federal

government has used the credit system to shape the

housing market. Policymakers enabled the expansion

of the suburbs starting in the 1930s, in part using

mortgage subsidies through the GSEs and the tax

code. The federal government has new opportunities

today to start building back a better housing market

through finance.

In support of the new Biden Administration’s broader

agenda focused on economic recovery, racial justice,

housing, health, and climate (which includes stated

plans to weatherize 2 million homes, retrofit 4 million

buildings, and build 1.5 million affordable new homes

50

),

the federal government can pursue the following:

•

Enable home performance labeling and disclosure

nationwide: Residents have a right to know about

the energy benefits or burdens of a home based

on its inherent physical assets before they move

in. Home energy labels highlight key information

about expected energy costs and cost-effective

improvement recommendations. Nationally

standardized ratings based on professional on-

site assessments—such as RESNET’s HERS for

new construction or DOE’s Home Energy Score for

existing homes—can be disclosed to prospective

buyers and occupants at time of listing and time

of rental.

The federal government can prioritize mandatory

home energy labeling nationwide and provide

resources and technical support for local

government implementation. This would enable

consumers to have better information when

budgeting and making housing choices, which can

especially help lower-income households identify

and avoid less tenable living situations.

Strengthening the link between these labels

and financing also enables borrowers to more

easily finance energy and other green home

improvements as part of their mortgages. Some

local governments have already established these

policies.

51

These can provide a model for scaling

access to energy labels nationally, which would also

drive up demand for green mortgage products to

complement supply-side efforts by the GSEs and

lenders. The costs of professional home energy

ratings could also be subsidized by the federal

government for LMI households.

•

Incorporate green home data fields into GSE

underwriting and appraisal standards: With or

without a national home performance disclosure

policy, FHFA can call on the GSEs to incorporate

key home energy and other green data fields

for all homes nationwide (not just for those with

certifications and ratings). This will help lay the

foundation for greater market efficiency. This would

be possible by, for example, adding a data field

for home-specific energy cost estimates into the

Uniform Appraisal Dataset (UAD) redesign initiative

(underway through 2021). The UAD could be auto-

populated for all homes by tools like NREL’s Home

Energy Cost Estimator, including homes that do not

have third-party ratings or certifications.

This tool is described in greater detail in Appendix

D. This one metric could then be used by lenders

to identify good candidates for green mortgages

and by appraisers and AVMs as a baseline for value

adjustments for home efficiency. This would also

allow for the collection of data over time that can

be aggregated and analyzed to better measure the

benefits of green homes for lenders, borrowers, and

capital markets investors.

•

Measure, disclose, and reduce GSE portfolio

emissions and climate risk exposure: Many of the

world’s largest banks and financial institutions

have committed to climate-align their portfolios

(i.e., bring lending and investment activities

into alignment with 1.5°C-consistent emission

pathways).

52

Similarly, the federal government

www.rmi.org

/

31Build Back Better Homes

through FHFA can call on the GSEs to start

measuring and disclosing carbon emissions

estimates for their portfolios, establish reduction

targets in line with federal climate goals, and

develop programs to reduce those emissions

accordingly. Existing DOE and market-available

tools can be leveraged to accelerate this

measurement process.

In addition, FHFA can work with other federal

agencies (e.g., NOAA, FEMA) to invest in or start

developing asset-level data that would enable the

GSEs to assess and disclose their portfolios’ climate

risk exposure to increasing floods, wildfires, winds,

sea-level rise, and other sources.

53

Scaling single-

family green mortgages can be a key tool for both

mitigation and adaptation.

•

Position mortgages to become a primary vehicle

for financing home performance and resilience

upgrades: FHFA could push the GSEs to provide

stronger incentives for lenders to market and

include their single-family green mortgage products

as built-in, opt-out options in all new and refinance

mortgage transactions. The resulting market size

and impacts could double or triple earlier estimates

as many more consumers could be reached with

information about cost-effective upgrades. This

would also drive broader market adoption as non-

agency and government mortgage lenders would

likely follow suit in offering similar product designs.

At a minimum, this mechanism could offer the

basic improvement financing by utilizing AVM-

based evaluations instead of full as-completed

appraisals to streamline origination for lenders.

The GSEs can help build out the green home

improvement market in this way, with the

labor need met quickly (as was the experience

in Portland and Austin with rating disclosure

ordinances). This would help meet the needs of

most US homes to make upgrades while also

aligning with the climate and ESG goals of major

lending institutions and capital markets investors.

• Although not the focus of this report,

the Departments of Housing and Urban

Development, Agriculture, and Veterans Affairs

already require newly built homes with FHA

loans and other federally assisted mortgages to

meet building energy codes (roughly a quarter

of mortgages for new homes). However, the

criteria are mostly still at 2009 code levels and

should be updated to 2021 code levels, which

would cut energy use of these buildings by at

least a third.

54

These agencies should adopt the

2021 code and the GSEs can be required to do

the same, ensuring that even more new homes

are built to high performance standards.

Conclusion

www.rmi.org

/

33Build Back Better Homes

Borrower Story #1:

A young couple was looking to buy a newly built

townhome as their first home, but they were unsure

that would be possible. When they found a new

townhome certified to the DOE Zero Energy Ready

Home standard, they were pleasantly surprised

to see how low the utility bills were estimated to

be on the real estate listing. They were even more

surprised when their loan officer told them the

energy savings compared to a standard new home

could be considered funds available to be spent

on their mortgage payments. Additionally, the

high performance certification on this home would

qualify them for a discounted interest rate.

The energy cost and interest savings amounted to

$100 per month—enough to allow them to afford

the home. Their mortgage was bundled as part of a

top-tier green MBS pool, enabling their lender and

Fannie Mae to claim ESG credit for the transaction.

What could this market look like in practice when fully up and running? Below are three

hypothetical stories of borrowers benefiting from a robust green mortgage and MBS market:

Borrower Story #2:

To get ready for a comfortable retirement, an older

couple living in a rural area added insulation to

their 1950s home and replaced their furnace with

a high-efficiency heat pump (both paid for with

cash savings). Through a local utility program they

received a Home Energy Score (HES) report that

rated their home an 8 out of 10.

After her husband died a few years later, the widow

decided to move closer to family and listed her

home for sale. When the eventual buyer informed

their loan officer of the home, the loan origination

software confirmed this home was a high performer

that would qualify as Group 3 green mortgage. The

buyer received preferential mortgage terms and

paid a slightly higher price for the home, allowing

the widow to more than recoup her investment in

the upgrades because the appraised value took into

account the high HES.

www.rmi.org

/

34Build Back Better Homes

Unlocking the single-family green mortgage and MBS

market is not only possible today—given advances in

data and automation as well as favorable financial

market and policy trends—it is also necessary. Five

years from now, conversations between friends and

neighbors about green home improvements financed by

mortgages and recognized in the transaction process

can become mainstream all over the country. Time is

of the essence to advance readily deployable solutions

capable of addressing the dynamic, intersectional

crises facing the housing market. Done correctly,

single-family green mortgage products can shift capital

and resources at scale to make living situations more

affordable, healthy, equitable, and resilient—better

serving American households and especially those who

stand to benefit disproportionately.

Scaling access to low-cost green improvement financing

is also in the mortgage industry’s best interests: it

offers an enormous new market opportunity catering

to both consumer and investor demand, while also

helping to future-proof the mortgage business itself

by mitigating ever-increasing climate risk. Mortgages,

through their inherent role in financing America’s

housing, can soon become a primary vehicle for

deploying billions of dollars toward these goals each

year. This report highlights targeted interventions

toward this end, but is also intended to serve as a

starting point in this continuously evolving space. A

coalition of home performance experts and other key

partners already collaborating with ambitious state and

local governments stands ready to support Fannie Mae,

Freddie Mac, FHFA, and other mortgage market leaders

in this important and timely pursuit.

Borrower Story #3:

A middle-income family was buying a move-up

house that needed some work. They were not first-

time home buyers so they felt they understood the

mortgage process. But they were pleased when the

loan officer saw that this home might have higher

utility bills and asked if they were interested in

financing green or energy-related improvements.

By this point they knew the house they were buying

had an old, inefficient water heater, was missing

crawlspace insulation, and had almost no insulation

in the attic. They were able to take advantage of

the basic eligible measures offered through Freddie

Mac to finance a new heat pump water heater and

new insulation. And they worked with a contractor

to have both projects installed within six months

after closing. They felt better knowing they had

created a more comfortable living environment for

their children.

Appendices

www.rmi.org

/

36Build Back Better Homes

Appendix A

Calculations and Assumptions

10-year impact estimatesExhibit A1

Certified New

Construction

High-

Performance

Deeper

Retrofits

Avg 25%

Savings

Basic

Retrofits

Avg 15%

Savings

Avg Loan

Amount

10-Yr Avg GSE Volume

Avg Project Cost

$12,500 $5,000 $250,000 $1,069,000,000,000

Growth

5% 10% 10%

Year

# New

Homes

#

Existing

Homes

#

Existing

Homes

Total

Homes

Mortgage

Volume

Project

Financing

Green Mortgage

Volume

% of

GSE Volume

1

70,000 90,000 450,000 610,000 $152,500,000,000 $3,375,000,000 $155,875,000,000 14.6%

2

73,500 99,000 495,000 667,500 $166,875,000,000 $3,712,500,000 $170,587,500,000 16.0%

3

77,175 108,900 544,500 730,575 $182,643,750,000 $4,083,750,000 $186,727,500,000 17.5%

4

81,034 119,790 598,950 799,774 $199,943,437,500 $4,492,125,000 $204,435,562,500 19.1%

5

85,085 131,769 658,845 875,699 $218,924,859,375 $4,941,337,500 $223,866,196,875 20.9%

6

89,340 144,946 724,730 959,015 $239,753,777,344 $5,435,471,250 $245,189,248,594 22.9%

7

93,807 159,440 724,730 977,977 $244,494,171,211 $5,616,653,625 $250,110,824,836 23.4%

8

98,497 175,385 724,730 998,611 $249,652,767,146 $5,815,954,238 $255,468,721,384 23.9%

9

103,422 192,923 724,730 1,021,074 $255,268,593,491 $6,035,184,911 $261,303,778,403 24.4%

10

108,593 212,215 724,730 1,045,538 $261,384,441,827 $6,276,338,652 $267,660,780,479 25.0%

Total

880,452 1,434,368 6,370,943 8,685,763 $2,171,440,797,895 $49,784,315,176 $2,221,225,113,071

Notes: Market size assumes year 1 green mortgages comprising 450,000 basic retrofits or 5% of all ~9 million annual single-family mortgage

loans, 90,000 deeper retrofits conservatively assumed at 1% of all loans, and 70,000 green new construction homes per proposed framework.

Combined this is just under 15% of GSE volume (half the level achieved by Fannie Mae’s multifamily green business), reaching 25% by year 10.

Basic and deeper retrofits are assumed to grow 10% per year (for basic, leveling off after year 5) and new construction at 5%. Other project-

level assumptions are detailed below. Cumulative impacts are based on weighted average savings (weighted by market share) for existing

home retrofits.

www.rmi.org

/

37Build Back Better Homes

Weighted Average

Savings

Weighted Average Net

Cost Savings

Weighted Average

Household CO

2

Savings

16.7% $316 1.45 metric tons

Year Retrofitted Homes Cumulative Net Savings

Cumulative CO

2

Avoided

(Metric Tons)

1

540,000 $1,706,400,000 7,803,000

2

594,000 $1,689,336,000 7,724,970

3

653,400 $1,651,795,200 7,553,304

4

718,740 $1,589,852,880 7,207,055

5

790,614 $1,499,004,144 6,854,623

6

869,675 $1,374,087,132 6,283,405

7

884,170 $1,117,590,867 5,110,503

8

900,114 $853,308,109 3,901,994

9

917,652 $579,956,376 2,652,016

10

936,945 $296,074,554 1,353,885

Total