A psychosocial study exploring children’s experience of their parents’ divorce or separation.

J. F. Stone

A thesis submitted for the degree of Professional Doctorate in Child, Community and

Educational Psychology

Tavistock and Portman NHS Trust

University of Essex

May 2019

2

Abstract(

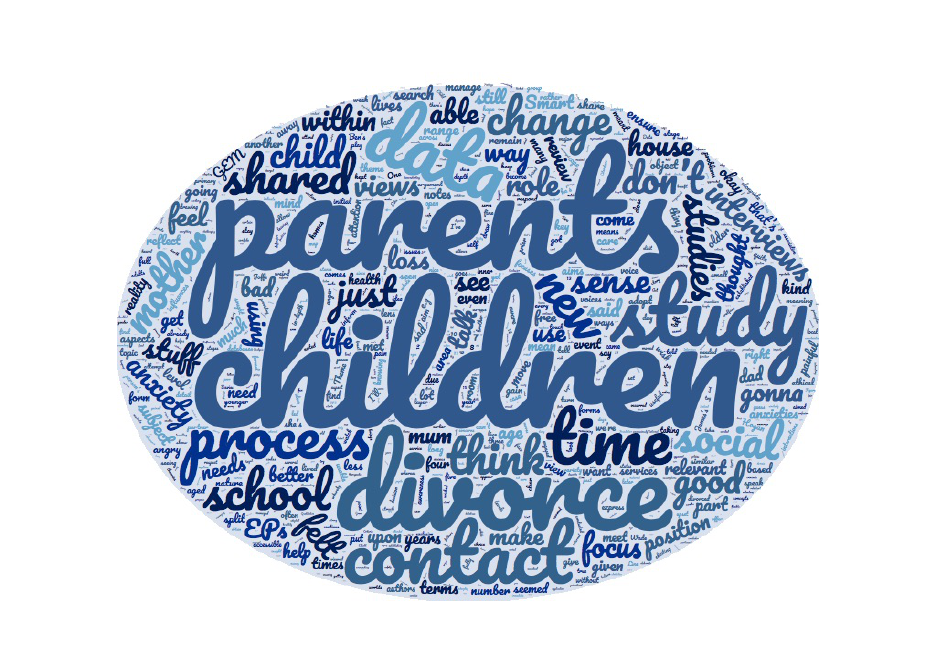

According to the Office of National Statistics (2018) an estimated 42% of marriages in England

and Wales now end in divorce, with half involving children under the age of 16. Despite growing

evidence of the impact of divorce and separation on children’s happiness, self-esteem and

behaviour there has been a paucity of research within the UK, which looks at children’s

experience of their parents’ divorce or separation. This psychosocial study aimed to explore the

experiences of children and young people whose parents have divorced or separated.

Four children and young people who had experienced the separation of their parents’ (three

males, one female) aged between 8 and 13 years old were interviewed twice about their

experience using two psychoanalytically informed, free associative methods; the Grid

Elaboration Method (GEM) and the Free-Association Narrative Interview (FANI). Data was

analysed using Thematic Analysis. A subsequent psychosocial layer of analysis was then

applied, using researcher field notes, to support an exploration of the dynamic, intersubjective

and unconscious processes present during the interviews. Five themes emerged from the data and

these are discussed alongside existing research and psychological theory. Unconscious processes

observed through the interview process are also explored. Implications for Educational

Psychologists (EPs), as well as schools and other professionals, when working with similar

populations of children and young people are considered. The studies limitations and thoughts

about future research are presented.

3

Acknowledgements(

This research would not have been possible without the children who agreed to take part. My

thanks goes to them and their parents who allowed me into their worlds to hear their stories. The

experiences you shared will have a lasting impact on me and I hope your voices will be heard

and your experiences better understood.

A big thank you to Cat for her enthusiasm and support for the study and for her support in

identifying two of the families who took part in the research. Without you identifying these

young people may not have been possible.

I would like to thank Rachael my research supervisor for her guidance and encouragement to

follow my heart and do the research I found most valuable.

A very special thank you to my Mum and Dad who have provided me with the opportunities to

achieve what I have, who always see the best in me, and have taught me the importance of

perseverance and hard work.

Finally, this thesis is dedicated to my husband to be, David, without you this would not have

been possible. Thank you for doing for me what I inspire to do for those that I work with;

containing my anxieties, giving me hope and inspiring me to be the best version of myself.

4

Table(of(Contents

Abstract(.................................................................................................................................(2!

Acknowledgements(................................................................................................................(3!

1.(Introduction(.......................................................................................................................(7!

1.1(The(National(Context(..................................................................................................................(7!

1.1.1!The!Prevalence!of!Divorce!and!Separation!in!the!UK!.................................................................!7!

1.2(The(Impact(and(Effects(of(Divorce(on(Children(............................................................................(8!

1.3(National(Policy(and(Legislation(for(Hearing(the(Voice(of(the(Child(.............................................(10!

1.4(Divorce(Research(and(Children’s(Views(.....................................................................................(11!

1.5(Educational(Psychology(and(Children(of(Divorce(.......................................................................(12!

1.6(Position(of(the(Researcher(........................................................................................................(14!

1.6.1!Psychoanalytic!Frameworks!in!EP!Practice!...............................................................................!16!

1.6.2!Terminology!..............................................................................................................................!17!

1.7(Chapter(Summary(.....................................................................................................................(17!

2.(Literature(Review(.............................................................................................................(19!

2.1(Chapter(Overview(.....................................................................................................................(19!

2.2(Search(Strategy(.........................................................................................................................(19!

2.2.1!Search!Terms!............................................................................................................................!20!

2.2.2!Inclusion!and!Exclusion!Criteria!................................................................................................!21!

2.2.3!Search!Returns!..........................................................................................................................!23!

2.2.4!Critical!appraisal!.......................................................................................................................!23!

2.3(Review(of(Literature(.................................................................................................................(23!

2.4(Researching(Children’s(Views(of(Divorce(and(Separation(..........................................................(24!

2.5(What(does(existing(research(say(about(children’s(experiences(of(divorce?(...............................(26!

2.5.1!Change!and!Transition!..............................................................................................................!26!

2.5.2!Children’s!Narratives!and!Positioning!.......................................................................................!35!

2.5.3!Decision!Making!and!Autonomy!...............................................................................................!36!

2.5.4!Support!and!Coping!..................................................................................................................!37!

2.5.5!Importance!of!Relationships!.....................................................................................................!41!

2.5.6!The!Role!of!School!....................................................................................................................!43!

2.5.7!Summary!of!Literature!Review!Question:!What!does!existing!research!tell!us!about!children’s!

experiences!of!divorce?!................................ .....................................................................................!46!

2.6(How(have(children’s(experiences(of(their(parents’(divorce(or(separation(in(the(UK(been(explored(

in(existin g (re s e a rc h ? (.......................................................................................................................(47!

2.6.1!Psychosocial!perspectives!.........................................................................................................!49!

2.7(Rationale(..................................................................................................................................(51!

3.(Methodology(....................................................................................................................( 53!

3.1(Chapter(Overview(.....................................................................................................................(53!

3.2(Research(Question(....................................................................................................................(53!

3.3(Research(Purpose(..................................................................................................................... (54!

3.3.1!Exploratory!...............................................................................................................................!54!

3.4(Research(Aim(............................................................................................................................(54!

3.5(Ontology(and(Epistemology(......................................................................................................(55!

3.5.1!Psychosocial!Ontology!..............................................................................................................!55!

3.5.2!Psychosocial!Epistemology!.......................................................................................................!56!

3.6(Methodology(............................................................................................................................(57!

3.6.1!Qualitative!Methodology!..........................................................................................................!57!

3.6.2!Psychosocial!Research!..............................................................................................................!58!

3.6.3!Psychoanalysis!in!Psychosocial!Research!..................................................................................!59!

5

3.6.4!Anxiety,!the!Defended!subject!and!Defended!Researcher!.......................................................!60!

3.7(Research(Design(.......................................................................................................................(63!

3.7.1!Participants!...............................................................................................................................!63!

3.7.2!Sampling!and!Recruitment!Procedures!....................................................................................!65!

3.7.3!Data!Collection!.........................................................................................................................!66!

3.7.4!The!GEM!...................................................................................................................................!67!

3.7.5!The!FANI!...................................................................................................................................!69!

3.7.6!Data!Capture!.............................................................................................................................!70!

3.8(Data(Analysis(............................................................................................................................(70!

3.8.1!Thematic!Analysis!.....................................................................................................................!72!

3.8.2!Psychosocial!Analysis!................................................................................................................!73!

3.9(Credibility(and(Trustworthiness(................................ ................................................................(74!

3.9.1!Sensitivity!to!Context!................................................................................................................!74!

3.9.2!Commitment!&!Rigour!..............................................................................................................!75!

3.9.3!Coherence!&!Transparency!......................................................................................................!76!

3.9.4!Impact!&!Importance!................................................................................................ ................!77!

3.9.5!Reflexivity!.................................................................................................................................!79!

3.10(Ethical(Considerations(............................................................................................................(80!

4.(Analysis(............................................................................................................................(84!

4.1(Chapter(Overview(................................ .....................................................................................(84!

4.2(Approach(to(Data(Collection(and(Analysis(.................................................................................(84!

4.3(Themes(.....................................................................................................................................(85!

4.4(Theme(1:(Response(to(Separation(.............................................................................................(89!

4.4.1!Past!&!Present!Feelings!............................................................................................................!89!

4.4.2!Processing!&!Understanding!....................................................................................................!91!

4.4.3!Re silie n ce!..................................................................................................................................!95!

4.4.4!Remembering!Experiences!.......................................................................................................!97!

4.5(Theme(2:(Relationship(Between(Parents(...................................................................................(98!

4.5.1!Feelings!.....................................................................................................................................!98!

4.5.2!Parental!Interaction!................................................................................................................!100!

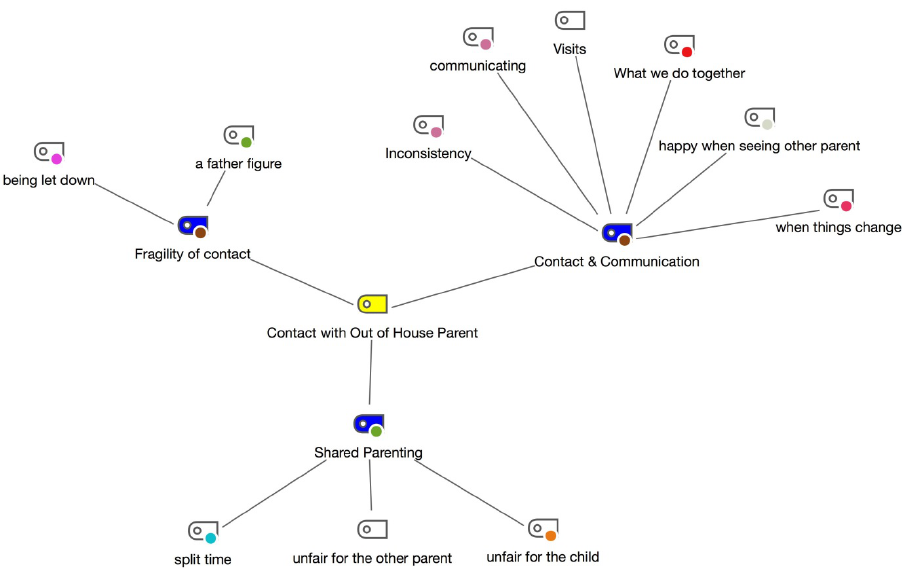

4.6(Theme(3:(Contact(with(Out(of(House(Parent(...........................................................................(102!

4.6.1!Shared!Parenting!....................................................................................................................!102!

4.6.2!Contact!and!Communication!..................................................................................................!103!

4.6.3!Fragility!of!contact!..................................................................................................................!105!

4.7(Theme(4:(When(Parents(Re-partner(........................................................................................(107!

4.7.1!Parents’!New!Relationships!....................................................................................................!107!

4.7.2!Additional!Family!Members!....................................................................................................!108!

4.7.3!Children’s!Perspectives!on!Parents’!New!Partners!.................................................................!109!

4.7.4!Subsequent!Separations!.........................................................................................................!111!

4.8(Theme(5:(Change(and(Continuity(............................................................................................(112!

4.8.1.!Parents!Living!Separately!.......................................................................................................!112!

4.8.2!Negative!Changes!...................................................................................................................!115!

4.8.3!Positive!changes!.....................................................................................................................!116!

4.8.4!Continuity!...............................................................................................................................!117!

4.9(Psychosocial(Analysis(..............................................................................................................(119!

4.9.1.!Ben,!aged!8!............................................................................................................................!119!

4.9.2!James,!aged!13!................................................................ .......................................................!122!

4.9.3!Sienna,!aged!11!.......................................................................................................................!125!

4.9.4!King,!aged!10!..........................................................................................................................!128!

4.10(Chapter(Summary(.................................................................................................................(131!

5.(Discussion(......................................................................................................................(132!

6

5.1(Chapter(Overview(................................................................ ...................................................(132!

5.2(Summary(of(Findings(................................................................................................ ..............(132!

5.3(A(Process:(Children’s(Response(to(Parents’(Sepa ratio n(...........................................................(133!

5.4(Relationships,(Contact (an d (S h a re d (P a re n tin g(..........................................................................(137!

5.5(Resilience,(Autonomy(&(Dependence(.....................................................................................(139!

5.6(Relating(in(role:(Individual(Intersubjective(Dynamics.(.............................................................(142!

5.7(Implications(for(the(Educational(Psychology(Profession(..........................................................(143!

5.8(Strengths(and(Limitations(.......................................................................................................(148!

5.9(Dissemination(.........................................................................................................................(151!

5.10(Future(Research(....................................................................................................................(151!

5.11(Reflections(............................................................................................................................(152!

5.12(Summary(..............................................................................................................................(153!

5.13(Conclusions(..........................................................................................................................(155!

List of Tables

Table(1.(Inclusion(and(Exclusion(Criteria(.........................................................................................(22!

Table(2.(Participant(Inclusion(and(Exclusion(Criteria(......................................................................(64!

Table(3.(Participants.(.......................................................................................................................(65!

Table(4.(The(Relationship(between(Themes(&(Subthemes(............................................................(86!

List of Figures

!

Figure(1.(Thematic(map(for(the(theme:(‘Response(to(Separation’(................................................(89!

Figure(2.(Thematic(map(for(the(theme(‘Relationship(between(parents’(.......................................(98!

Figure(3.(Thematic(map(for(the(theme:(‘Contact(with(Out(of(House(Parent’(..............................(102!

Figure(4.(Thematic(map(for(the(theme:(‘When(Parents(Re-Partner’(...........................................(107!

Figure(5.(Thematic(map(for(the(theme:(‘Change(&(Continuity’(...................................................(112!

7

1.(Introduction((

1.1(The(National(Context(

Divorce and parental separation transcends race, ethnicity, religion, and socio-economic status

(Amato & Cheadle, 2008). It is a recognised life event for children across the globe and its

prevalence and nature has been studied in countries including the United States, Australia, and

Ireland. (Campbell, 2008; Halpenny, Greene, & Hogan, 2008; Hans & Fine, 2001). This study

focuses on the experience of children and young people who have experienced the divorce or

separation of their parents in the UK. When considering prevalence, policy frameworks, impact

and implications, the UK context is the primary field of study.

1.1.1(The(Prevalence(of(Divorce(and(Separation(in(the(UK(

An estimated 42% of marriages in England and Wales now end in divorce (Office of National

Statistics (ONS), 2018). Out of the over 11 million children in England, it is thought that 3

million will experience the separation of their parents during the course of their childhood

(Bailey, Thoburn, & Timms, 2011), meaning one in three will experience divorce before the age

of 16 (Maclean, 2004). There is no formal registration of cohabitation, or separation of

unmarried parents, therefore, we cannot be precise about the number of children who experience

the separation of their unmarried parents (Hawthorne, Jessop, Pryor, & Richards, 2003).

However, it is thought that the figure is probably not too dissimilar to those who experience

divorce, suggesting the number of children who experience divorce or separation is considerable.

8

1.2(The(Impact(and(Effects(of(Divorce(on(Children((

A growing volume of research has commented on the potential impact on children of living

through their parents’ separation. These highlight a complex range of emotional, economic,

educational and social problems which may be experienced by children before, during, and after

the breakdown of their parents’ relationship (Bailey et al., 2011). Data from the Mental Health of

Children and Young People Survey (2004) found a significant association between children

living with a divorced or separated lone parent and associated mental health needs. Children

were 75% more likely to experience a mental health disorder than children living with their

married parents (Green, McGinnity, Meltzer, Ford, & Goodman, 2005). Studies indicate that

there are immediate and long term effects for children who experience parental divorce with

growing evidence to suggest the impact of divorce and separation on children’s unhappiness, low

self-esteem and behaviour (Maclean, 2004). The stress of parental divorce can impact negatively

on the child’s academic and psychological development and they are more likely to have

emotional and behavioural challenges as well as increases in anxiety and depression (Huurre,

Junkkari, & Aro, 2006; Molepo, Sodi, Maunganidze, & Mudhovozi, 2012; O'Connor, Thorpe,

Dunn, & Golding, 1999; Pagani, Boulerice, Tremblay, & Vitaro, 1997).

Most children who experience the breakdown of their parents’ relationship go through a period

of unhappiness and many experience low self-esteem and loss of contact with family members

(Rodgers & Pryor, 1998). However, most do settle back into a normal pattern of development

(Rodgers & Pryor, 1998). Rodgers and Pryor (1998) and Hawthorne, et al., (2003) reviewed the

impact of divorce and separation on children. They found that these children have twice the

probability of experiencing poor outcomes compared with those in intact families, with the

possibility of these being observed years after separation, even in adulthood. The reviews

summarised that these children have higher probability of low family income, behavioural

9

problems, negative performance in school, depressive symptoms and substance misuse. Several

factors were found to contribute to these outcomes including family conflict, quality of

parenting, parental ability to recover from distress of separation, multiple changes in family

structure and the child’s ability to manage stress.

Parental separation can be a significant upheaval and catalyst of change in many children and

young people’s lives, with many experiencing diminished or no contact with one parent, reduced

parental availability, the management of two households and routines, and the possibility of

ongoing inter-parental conflict and anger (Halpenny et al., 2008). Research suggests that

children from separated families when compared with children who have experienced the death

of a parent experience greater risks of poorer educational attainment, lower socio-economic

status and poorer mental health. Although both share the impact of parental loss, bereaved

children are not as adversely affected across the same range of outcomes as children whose

parents have separated (Rodgers & Pryor, 1998). However, it is thought that most children grow

up and function within normal or average limits and it is only a minority who experience long

term adjustment problems (Fawcett, 2000). It is important here to acknowledge the heterogeneity

of divorce and separation. The variety of familial, contextual, psychological and social

circumstances surrounding individual experiences of divorce and separation contribute to its

many forms and, therefore, it is likely that experiences and impact will vary significantly

between families and individuals. This is something hoping to be addressed in this study, which

focuses on the individuality of experience. In order to know how to help to support children it is

important to understand their experiences. The following section explores the current picture

around hearing the voice of the child in relation to their experience.

10

1.3(National(Policy(and(Legislation(for(Hearing(the(Voice(of(the(Child((

There has been growing interest and legislation that reflects the importance of children and

young people sharing their views and participating in decisions about themselves. Article 12 of

the United Nations Convention on Rights of the Child, ratified by British government in 1991,

ensures that children have a right to express an opinion and have that opinion considered in any

matters affecting themselves. This has become an established tenet of many UK policies and

legislation (Bailey et al., 2011). In the UK, the main legislation covering arrangements for

children when their parents’ divorce or separate is the Children Act 1989, which has been

amended in relevant sections by the Adoption and Children Act 2002, the Children and Adoption

Act 2006, and the Children and Families Act 2014. These provide for residence and contact

orders relating to children to be made, to promote and safeguard the welfare of the child if there

are disputes about parental responsibility within post-separation arrangements (Bailey et al.,

2011).

Government initiatives (DCA & DfES, 2004; DfES, 2005) have proposed changes to divorce

legislation, with the aim to improve outcomes for children and make fundamental changes to the

way in which private law disputes are dealt with by the courts (Timms, Bailey, & Thoburn,

2007). In September 2018, the government put forward for consultation a reform of the legal

requirements for divorce, to shift the focus from blame, towards supporting adults to focus on

making better arrangements for their own futures and their children, with focus on improving

outcomes for children, by minimising conflict, and strengthening family responsibility (Ministry

of Justice, 2018).

Considering this legislation, research that focuses on children’s experience of their parents’

separation would arguably provide a more comprehensive understanding of what children think

11

and feel about this event. Previous research shows that children’s responses to family change are

diverse and varied, however, a focus on group related outcomes disguises the diversity and

individuality of each child’s experience and outcome (Hawthorne et al., 2003). What stands out

is that children have views and perspectives that they want heard and it is in their best interest to

be listened to, as decisions made have considerable impact on their lives (Hawthorne et al.,

2003). Weidberg (2017) references that if children are given a voice it can impact on educational

reform and lead to progress with policies and practice. Research that gathers children’s views

and allows them to be the experts in their own worlds not only provides a richness to data

gathered but can enhance professionals’ understanding of how a child experiences and makes

sense of an event, such as divorce.

1.4(Divorce(Research(and(Children’s(Views(

“Among the shouting there are voices that are not being heard: the children’s”

(Chen & George, 2005, p. 452)

The voice of the child can often be missed in the parental divorce process, however, given

children’s responses to divorce and separation are varied, research which considers the

perspectives of children can contribute to the establishment of appropriate support and

interventions (Hawthorne et al., 2003; Hogan & O’Reilly, 2007). Hawthorne et al., (2003)

suggest that services that are set up to support children and young people who are experiencing,

or have experienced divorce or separation, may be more effective, if those establishing them first

consult the children. Children’s views and experiences are slowly becoming acknowledged and

researchers have come to recognise the advantages of talking to children directly about their

experiences rather than relying on adult mediated accounts (Brand, Howcroft & Hoelson, 2017;

Hogan, Halpenny & Greene, 2003). Several studies contribute to the current understanding of

12

children’s experiences of parental divorce in different areas. Past research has explored

children’s views on their involvement in court proceedings (Timms et al., 2007), capturing the

views of children whose parents were married and seeking a divorce. Other research has sought

children’s views on the mechanisms through which they can best be supported in the context of

family transition (Halpenny et al., 2008; Hawthorne et al., 2003; Wade & Smart, 2002), their

perceptions of contact arrangements (Trinder, Beek, & Connolly, 2002) and relationships with

family members post-divorce (Abbey & Dallos, 2004; Bridges, Roe, Dunn, & O'Connor, 2007).

Campbell (2008) in his research about children’s views on decision making following parental

separation strongly advises that it is increasingly important to hear directly from children to

ensure we focus on their best interests and meet their needs.

1.5(Educational(Psychology(and(Children(of(Divorce(

Parental separation is most helpfully viewed as a process, which begins before divorce or

separation of parents, and continues throughout the person’s life. Children or young people

might require support or intervention at any stage in this process (Maclean, 2004; Rodgers &

Pryor, 1998). The development of intervention programmes and policies can be better informed

through understanding the experiences and perceptions of children regarding parental divorce

and should be of value to professionals such as psychologists, teachers and social workers

(Brand et al., 2017).

Current legislation (Special Educational Needs Code of Practice, 2015; Every Child Matters

(ECM), 2003) emphasises the importance of a family and person-centred system which works in

partnership with parents, and involves children in discussions and decisions about themselves, to

ensure best outcomes for children (DfES, 2003; DfE & DoH, 2015). EPs are well placed to help

support and promote positive outcomes for young people by focusing on their needs and well-

13

being. Mercieca and Mercieca (2014) posit that listening to young people is an integral part of

the role of the EP. Furthermore, EPs have the skills and opportunities to naturally elicit

children’s views and communicate with those around them to formulate a holistic and

psychologically informed understanding of their complex individual and social needs (Maclean,

2004; Weidberg, 2017; BPS, 2002) .

In recent years, there has been a growing focus on the mental health and wellbeing of children

and young people. A greater understanding of how children experience parental divorce or

separation can assist the provision of social, emotional support through the education system,

which, ECM (DfES, 2003) highlights, has a pivotal role in offering support to all children who

experience a variety of stressors throughout childhood. Research into the impact of divorce or

separation on children has highlighted both immediate and long term effects on children’s social

and emotional wellbeing, happiness and mental health, which is recognised as being directly

linked to their capacity to learn and academic standards (Ubha & Cahill, 2014). The recent

Government green paper ‘Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision’

(DoE & DoHS, 2017) promotes the importance of ‘a whole school approach that embeds the

promotion of wellbeing throughout the culture of the school and curriculum, as well as in staff

training and continuing professional development’. EPs work with the child, their family and

other adults who teach and care for them in their support of children with SEMH needs (BPS,

2002), and are well placed to take a holistic view of a child’s needs, considering the range of

different social and environmental contexts within which they operate (Billington, 2006). The

knowledge EPs bring of dynamic processes in relationships, the functioning of systems

(including the family system) and their understanding of theories of development can put them in

a crucial role in supporting others to understand the experiences of children who are in the

process of or have experienced their parents’ divorce or separation. Through the provision of

14

training or consultation, EPs can promote awareness and understanding of children’s experiences

and needs, and have the potential to improve outcomes and promote positive change for these

children and young people.

1.6(Position(of(the(Researcher(

(

This psychosocial research aims to explore children and young people’s experience of their

parents’ divorce or separation and hopes to illuminate and enable further understanding of their

experiences from a psychoanalytic perspective. A psychosocial stance allows both the

psychological and social to be considered together when interpreting data and conceptualizes

participants as both products of a shared social world and their unique psychic worlds (Gadd &

Jefferson, 2007). A psychosocial approach considers the interrelatedness of individual

psychological and social experiences of research participants and also allows me, the researcher,

to consciously consider my role, relation and presence throughout the research process, and its

impact on myself, the participants, the data produced and the conclusions drawn. I will now

address the four overarching influences that have led me to adopt a psychosocial stance and

address the research topic in this way.

My academic and working background in psychology, psychotherapy and socio-cultural

phenomena has influenced the lens through which I attempt to understand and gain insight into

an individual’s experience. This includes considering societal, cultural and psychological factors

on the impact of phenomena on individuals. My EP training, which has exposed me to

psychoanalytic and systems theories as frameworks for understanding phenomena, further

contributes to how I view and interpret the world and the application of psychology in my

practice. I believe through employing a psychosocial lens, I can gain an understanding of

unconscious processes that shape an individual’s narrative about an experience, and that

15

children’s narratives related to experiences of divorce or separation, are shaped by an interplay

of influences.

Two further influences have encouraged my interest in this research area. Firstly, my

experiences as a behaviour mentor in a pupil referral unit for children with social, emotional and

behavioural needs and as a Trainee EP exposed me to a number of children who have

experienced the divorce or separation of their parents. Each individual child presented a unique

story, with an individual response and individual social experience. This contributed to my

curiosity as to what impacted on these experiences and the children’s response to them. It is also

important to note my own individual experience of divorce. My parents are divorced and with

three siblings, our own experience and response to this event has been unique and individual,

sparking my own curiosity further about the individuality of our psychological and social

realities. Clarke & Hogget (2009) recognise the importance of a researcher acknowledging these

“inner dynamics” that may spark professional interest. Reflection and reflexivity are key tenets

of psychosocial research and allow researchers to reflect on their own subjective responses and

the unconscious intersubjective dynamics in field encounters (Hollway, 2015).

Psychosocial influences shape and construct a researcher’s world view as well as each

individual’s uniquely constructed narrative of their experience. This is true also for any

interpretation of the meanings behind an individual’s articulation of their experience.

Psychoanalysis provides a framework to help researchers make meaning throughout the research

process, with focus on the unconscious intersubjective communications between the researcher

and researched in that context, making the encounter a co-constructed reality (Hollway, 2015).

This interaction can be understood further using a psychosocial lens, and helps to consider what

the researcher attends to, how they attend to it and why, as well as what is communicated and

16

how, and how this is influenced through the context of the interview. Paying attention to these

phenomena can support the researcher to reflexively consider their role in this dynamic research

encounter (Hollway, 2015).

Smart (2006) found some children were unable to provide full accounts when asked about their

experience of divorce. This psychosocial research is of the premise that both the researcher and

researched may engage in unconscious defences against anxiety, motivating the positions they

take up and the accounts they portray (Hollway & Jefferson, 2013). Therefore, it is thought that

when speaking about their parents’ separation or divorce, children may have difficulty

expressing their experiences entirely through verbal accounts and their narratives may be

influenced by unconscious processes, impacting on how they articulate their experience.

Through paying attention to unconscious processes within the interview context, it may be

possible to gain a deeper understanding of both their conscious and unconscious communications

of their experience.

1.6.1(Psychoanalytic(Frameworks(in(EP(Practice(

In the context of this research, psychoanalysis focuses on the possible unconscious dynamics and

defences that can present themselves when speaking with children about their parents’ separation

or divorce. Psychoanalytic frameworks are one way EPs can inform their understanding of their

work with individuals and within groups or systems, however there is little research evidence to

suggest that EPs use psychoanalytic frameworks in their practice (Eloquin, 2016). EPs are

applied psychologists and the use of psychodynamic ideas elevate the central place of emotion in

human experience and the significance of development in how the “there and then” may play out

in the “here and now” (Kennedy, Keaney, Shaldon, & Canagaratnam, 2018). It allows for a more

17

reflective view of relational dynamics, encouraging awareness of inter-subjectivity and the

emotions that can pass between people. Knowledge and awareness of the presence of

transference and counter-transference in interactions can provide containment and support

avoidance of acting out what is being transferred. Noticing and paying attention to these

defensive manoeuvres, can allow them to be thought about and better understood in service of

the individuals and systems in which EPs work (Kennedy et al., 2018).

1.6.2(Terminology(

Separation and divorce, for the purposes of this research, have been interpreted to mean when

children’s biological parents no longer identify as being in a relationship with each other. The

study honors the heterogeneity of experience and, therefore, these terms will be used

interchangeably throughout this paper.

1.7(Chapter(Summary(

This research aims to explore the experiences of children and young people whose parents have

separated or divorced. The national picture of divorce and separation is hard to be determined

given the number of parents who choose to cohabit, rather than marry. However, it is thought

that the number of children who experience this event is significant. Divorce impacts on a range

of outcomes for children including their academic, psychological and socioeconomic

development. Outcomes for children continue to be a focus nationally regarding their mental

health and wellbeing and recently children’s views are considered important in understanding

their perceptions of specific life events. However, there is still little research that explores their

views in relation to divorce or separation of their parents. The role of the EP, with regards to

their involvement in eliciting children’s views and working with families and systems, has been

18

highlighted; ensuring this research poses relevance. The position of the researcher has also been

introduced. Having introduced the topic being studied, a critical literature review will now

situate the study in existing UK-based literature.

19

2.(Literature(Review(

2.1(Chapter(Overview(

This chapter describes the systematic and comprehensive approach taken to reviewing the range

and quality of the literature in relation to children and young people’s experience of their

parents’ divorce or separation. The aims were to:

• Establish what is already known and enhance understanding of children and young

people’s experiences of divorce by describing the findings of previous research.

• Critically appraise relevant research; and

• Justify the aims, rationale, and research questions of the present study.

The findings are synthesised and reported in relation to addressing two literature review

questions:

1) What does existing research tell us about children and young people’s experience of their

parents’ divorce or separation?

2) How have children’s experience of their parents’ divorce or separation in the UK been

explored in existing research?

2.2(Search(Strategy(

A search of databases PsycINFO, SocINDEX and PEP Archive was carried out on 21/04/2018. It

was felt that these databases were appropriate and useful for this psychosocial study, as they

contained reputable British psychological and educational journals; key psychoanalytic and

20

sociology journals and were felt to meet the focus of this study by transcending the split that

often exists between psychology and sociology in research.

A second search was carried out on 16/08/2018 using the same search terms to identify any

additional studies. At this point SocINDEX database had been discontinued and was unable to be

included in this search. No additional studies were found. Education Source database was

searched in addition to the above databases, to ensure all possible relevant literature was

included in the final review. No new returns resulted from this database search.

A manual search of the two reputable Educational Psychology journals in the UK – 1)

Educational and Child Psychology and 2) Educational Psychology in Practice was carried out on

02/08/2018 from available issues published between 1991-2018. No relevant studies were

acquired from this. This is an interesting discovery considering the number of children and

young people affected by the divorce or separation of their parents’ and the role of EPs in

working with these children and their families.

Finally, considering the limitations of databases and aiming to get as broad a scope of the

literature on divorce and separation as possible, a search of papers published by The Joseph

Rowntree Foundation was carried out. The Joseph Rowntree Foundation is a reputable research

organisation that focuses on social change.

2.2.1(Search(Terms(

Pilot searches were carried out using the above databases to refine search terms and to ensure the

most useful terms were used in the final search to capture relevant literature. The thesaurus

21

function was used to identify relevant terms. The following terms were used to identify

literature, Boolean operators “AND” and “OR” truncations were used as necessary:

Children, young people, teenager, adolescent, young adult, youth, school children

Divorce, children of divorce, marriage breakdown, marriage dissolution, marital

separation, children of divorced parents, relationship termination

Experience, views, voice, lived experience

The above databases were searched individually using the above search terms. To identify papers

related to relevant populations age was used as a limiter; Age: childhood (birth-12 years), school

age (6-12 years) and adolescence (13-17 years).

Initial searches identified that the subject term ‘parental separation’ resulted in hits associated

with parental attachment and parent-child separation so it was decided to remove this from the

final search, having checked subject terms with the database thesaurus.

2.2.2(Inclusion(and(Exclusion(Criteria(

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established in advance of conducting the searches to ensure

that the research selected was relevant and appropriate to the study (Table 1).

22

Table(1.(Inclusion(and(Exclusion(Criteria(

Inclusion Exclusion

Language: published in English

Position papers, editorials, book reviews

Empirical papers

Papers with a focus on a specific population e.g.

SEN

Peer reviewed

Papers that focus on others views or experiences

e.g. parent, teachers.

Research conducted in the UK

Papers looking to measure or evaluate the

efficacy of interventions e.g. court interventions,

mediation services

Literature that focuses on children and young

people’s experiences and views of divorce

Papers that focus on children’s experience of the

court process specifically e.g. children’s

experience of mediation or intervention

Literature that focuses on children of school age

4-18

Papers with a focus on outcome, correlational or

mediating factors of the impacts of divorce

Literature where the focus is a subject other than

divorce or separation

Research published before January 1991

UK papers were selected for relevance to the UK education system, in which Educational

Psychologists conduct their training and work, also due to the population and national divorce

statistics that have been commented upon in relation to this research. Research published after

January 1991 were included as this is when Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on

Rights of the Child was ratified by British government.

23

2.2.3(Search(Returns(

An initial search using the subject term ‘children of divorce’ was conducted using the above

databases and applying the chosen limiters, resulting in 28 papers. 18 papers were eliminated

based on the titles and abstracts (see Appendix 1 for excluded articles) and 2 were duplicates. At

this stage 7 articles were included.

Combined searches carried out on 21/04/2018 and 16/08/2018 resulted in 108 hits after

eliminating studies from outside of the UK. 96 papers were eliminated from reading titles and

abstracts and applying them to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A further 11 studies were

duplicates. One additional study was included from this search. Two papers were also returned

from The Joseph Rowntree Foundation search. These final 10 papers were then read in full and

checked for quality (Appendix 2).

2.2.4(Critical(appraisal(

Papers were screened for quality using Walsh and Downe’s (2006) appraisal tool for qualitative

research (Appendix 3 & 4) . This tool was selected for its suitability to appraising qualitative

research and its inclusion of reflexivity in the appraisal criteria, an important component of

psychosocial research.

2.3(Review(of(Literature(

There is a dearth of research within the UK which looks at children’s experiences of their

parents’ divorce or separation. There were also no identified articles in two key UK EP journals

24

that looked at children’s experiences of divorce. The systematic literature review highlighted

that there has been an increase in research over the past 15-20 years looking at children’s

perspectives around the topic of divorce, in many western countries. However, a large proportion

of this research focuses on the court process linked with divorce and evaluations of mediating

interventions. Of the papers returned, sociologists and social workers authored eight of the

papers. Only one was authored by a psychologist indicating most divorce literature appears to be

carried out within the area of sociology and social care. This is not unexpected considering the

nature of social change associated with divorce and its focus on the family. However, it is

surprising that the presence of psychologists, especially EPs, within this domain appears to be

slim, considering their assumed regular contact with families and children who have or are

experiencing divorce or separation. Five of the papers found were based on research undertaken

through the same research centre, which may impact on the way the subject is addressed in the

literature, and the range of ontological and epistemological positions adopted.

The literature review revealed that children, parents and professionals have all participated, to

varying degrees in research around divorce and separation. This research intends to focus on

children’s experiences of divorce or separation, therefore, only papers with this focus have been

included. The papers including both child and parental experiences have been included;

however, priority is given to the findings that focus on children’s experiences. The next section

will present the identified papers in line with the literature review questions.

2.4(Researching(Children’s(Views(of(Divorce(and(Separation(

Broadly speaking, the research reviewed here can be broken into two overarching themes;

change and transition, linked closely to contact arrangements; and support and coping. Linking

25

these themes together is the theme of relationships. Whilst some of the papers focused primarily

on one of these areas, others reported on both.

The reviewed literature demonstrates a number of examples which explore the views of children

and young people who have experienced divorce or separation and feel they are best placed to

further understand the diversity of their experience of this process (Davies, 2015; Dowling &

Gorell-Barnes, 1999; Fawcett, 2000; Flowerdew & Neale, 2003; Neale, 2002; Neale &

Flowerdew, 2007; Smart, 2006; Wade & Smart, 2002). Dowling & Gorell-Barnes (1999),

acknowledge that it can be difficult for children to be heard when parents decide to divorce or

separate. It is reasoned that through children talking about how they perceive and experience

divorce that it is possible to detect what positons children themselves actively adopt (Smart,

2006). Several of the reviewed papers come from a sociological perspective whereby child

participation is considered alongside perspectives of welfare and citizenship (Fawcett, 2000;

Neale, 2002; Neale & Flowerdew, 2007; Wade & Smart, 2002). Changes in sociological

perspectives of children has promoted children as social agents, who are capable of thinking for

themselves and who are considered young citizens in their own right, entitled to recognition,

respect and participation (Neale & Flowerdew, 2007; Wade & Smart, 2002). These papers

propose a view of moving beyond seeing children as in need of care and protection, as suggested

by welfare paradigms, and instead integrating welfare and citizenship balancing ‘care with

respect, and protection with participation’ (Neale & Flowerdew, 2007, p. 27). By incorporating

children’s voices into research they have the possibility to be transformed from ‘invisible objects

of research inquiry to active research subjects with legitimate voices of their own’ (Neale &

Flowerdew, 2007, p. 27).

(

26

2.5(What(does(existing(research(say(about(children’s(experiences(of(divorce?(

2.5.1(Change(and(Transition(

Five papers centered their research around the aspect of change that occurs for children and

young people who experience divorce. Change and transition is conceptualised in different ways

by the authors and considers aspects of shared parenting, contact arrangements, contextual

changes, time and pace of change and management of change.

Flowerdew & Neale (2003) contest the notion of ‘multiple transitions’, suggesting that literature

in this area is limited to changes associated with parental re-partnering twice or several times

over. They aim to refine the notion of ‘multiple transitions’ and provide new insights into the

way young people manage change, through exploring young people’s perceptions and

understandings of the impact of changes, the pace and nature of change and the different

contexts in which changes occur (Flowerdew & Neale, 2003). Sixty young people aged 11-17,

from the north of England, living in post-divorce families, were contacted 3-4 years after their

involvement in two linked projects. The sample was balanced in terms of age, gender and social

background and they recruited from a variety of routes to avoid an exclusively legal or

therapeutic sample. Authors organised their discussion into four themes: ‘getting used to’ family

change; the management, pace and cumulative nature of change; the quality of relationships; and

divorce as an ‘everyday’ challenge. However, the limited information on the design and analysis

involved in the study makes it difficult to determine the quality of the analysis and recruitment

methods. Encouragingly, the authors mention paying attention to ethics of conducting research

with children. Findings suggested that stepfamily life brought economic benefits and that largely

positive experiences were reported by the participants. The study recognises some of the

difficulties children face when adjusting to stepfamily life including, moving home, dealing with

27

new stepparents, adapting to family routines and finances, coping with stepsiblings, and learning

to ‘share’ parents and domestic spaces.

Other findings from children’s experiences highlight a sense of loss at the transition from a lone

parent family back to a two-parent family, which authors suggest is afforded less recognition in

the literature. Children appeared to manage change and transition more positively when only one

parent re-partnered at any one time and found it harder when the pace of change was accelerated

and multiple transitions occurred in a short space of time. Conclusions suggest that divorce is an

everyday problem for some children, however, others continue to be preoccupied and perplexed

by experiences, suggesting the individuality and specifics of experience and its impact on coping

with change. It was noted that the management, timing and pace of change emerged as a critical

factor in how young people cope (Flowerdew & Neale, 2003). This study helpfully highlights

children’s experiences and uses extensive interview quotes to present children’s voices in

relation to coping with change and transition. However, in a bid to ‘decenter divorce’ and

highlight other potential important challenges in the lives of young people it fails to fully

acknowledge the full breadth of young people’s experiences. The researchers do not mention any

influence from researcher involvement and acknowledgment of reflexivity is missing

considerably in this study.

Dowling & Gorell-Barnes’s (1999) project aimed to support children to find a way to describe

their experience of divorce. The authors set out to determine the protective conditions which

were likely to make it possible for children to cope with the transition of divorce and separation.

They interviewed 10 families and children aged 5-14 years attending family therapy. The study

takes the form of individual case studies and a comprehensive description of data gathering is

provided, however, there is no discussion of how the data was managed or analysed. The study

28

does not select a homogenous sample, respecting the individuality of experience. However, it is

not clear how the researchers decided upon these 10 families other than they were referred for

family therapy. Surprisingly, given the therapeutic sample there is no mention of reflexivity from

the researchers. Children’s experiences involved changes to contact with the out of house parent

and contextual changes including moving to a new house, school, sharing a room, and adapting

to stepfamily life. A key narrative, was children having to manage and mediate relationships

with and between parents, often having to negotiate transition from one parent to another amid

quarrelling and discord. Children at times found themselves in ‘loyalty binds’, wanting to

maintain positive relationships with both parents and unsure or unable to share that they are

enjoying their time with the other parent. Dowling & Gorell-Barnes (1999) suggest that some

children do not have a coherent story of the marital breakup, leading to confusion and anger.

There were also reported developmental and gender differences; younger children may become

clingy and fear the other parent leaving, whereas older children may express their anxieties

through acting out or failing at school. Girls were more likely to suggest that parents should talk

to their children about what is going on whereas boys felt the children should just grin and bear

it. The paper concludes by highlighting the different clinical considerations that arise from

children who experience divorce and goals for a specific model in working with families going

through divorce. Due to the clinical nature, the generalisation to non-clinical samples is tentative.

Unlike Morrison (2015) and Trinder et al. (2002), where parents were also involved in the study,

Dowling & Gorrell-Barnes (1999) have chosen only to report on the children’s experience,

prioritising their subjective experiences.

Fawcett (2000) found findings consistent with above regarding the changes and transition that

children experience. Fawcett (2000) reported on the individual, unique and complex shifting

process, affecting children’s lives, which usually began before parents separated and continued

29

months and years after the marriage breakdown. This included emotional reactions; upset and

distress (anger, sadness, confusion and relief) and widespread practical and social changes such

as, house moves, school moves, living with different people, extra responsibilities and less

money. Fawcett interpreted a sense of both resilience and lingering sadness present for children

after the separation.

2.5.1.1%Shared%Parenting%

Children’s experience of shared parenting and contact arrangements were explored by four of the

studies (Davies, 2015; Morrison, 2015; Neale & Flowerdew, 2007; Trinder et al., 2002). The

studies present changes children face with regards to contact with their parents and associated

contextual changes, which may take several forms depending on the relationship between

parents.

Davies (2015) used a case study to present three siblings (aged 8-10) experiencing post-divorce

shared parenting arrangements. She explored whether the term ‘shared care families’ may better

conceptualise ‘shared parenting’ as it enables understanding of resources and different

individuals necessary to support ‘shared parenting’ arrangements. Children’s accounts were

generated from a school-based field study investigating their constructions and experiences of

family and close relationships, over 18 months. The study involved participant observation,

children’s drawings, family books, visits to children’s homes and two sets of paired interviews.

The family of children were recruited to take part based on their successful and consensual

shared parenting arrangements and their relatively well resourced financial circumstances. The

sample strategy for the original field study is not described and the reasons for selecting a

relatively well financially resourced family over the other shared parenting children is not

explained. The study provided a thorough description of its abductive approach to analysis and

30

how themes were derived. Themes generated were developed alongside existing themes from

research in family life and parenting, and combined with themes that emerged from the data.

Themes were ‘sibling relationships in shared family arrangements’; shared parenting: ‘fairness

for parents’; reciprocity of care; and equal share and equal care. Davies (2015) interpreted that

attributes of successful shared parenting arrangements were underpinned by shared cooperative

relationships and were socially and materially well resourced. The need for space was

emotionally important for children and this was highlighted as a difficulty to obtain when

families re-partner and introduce step- and half-siblings, limiting children’s opportunities for

peace, quiet and private space. Children’s views portrayed a principle of fairness and spending

equal time with both parents. Although, the children attached value to sharing equal time, it was

implicit in the children’s words that it was more important for parents. Additional factors were

parents living close enough to each other so children could attend the same school and the

involvement of grandparents and kin in the care of the children. Davies (2015) recommends that

shared parenting should be re-conceptualised as ‘Shared Care’. This is considered with

recognition to lower income families who are not materially or socially well-resourced. The

financial burden of shared care is noted and considered as reasons why fewer lower income

families go into consensual shared care arrangements. This study helpfully highlights some of

the factors which support shared parenting through the eyes of children. It applies this to socio-

economic status and places an argument for reconceptualisation of terminology to support those

without the means to adopt a parenting arrangement of this kind. However, the study could have

included the lower income families as means to demonstrate what works for them and therefore

the assumptions made regarding how this arrangement wouldn’t work for lower income families

is difficult to give much weight to.

31

Morrison (2015) focused on children’s and mothers’ experiences of contact when there has been

a history of domestic abuse. Morrison (2015) used participative research activities with 18

children aged 8-14, which included a ‘storyboard’, a pictorial vignette, and a ‘My Story’ activity

which encouraged children to map their experiences of contact onto paper. Sixteen mothers who

had experienced domestic abuse in Scotland were also interviewed and recruited from domestic

abuse support services in the voluntary and statutory sectors. The study reported that continued

abuse of women and children following parental separation was linked to contact arrangements.

Children’s contact with non-resident fathers often took place amongst an absence of parental

communication and cooperation. These left children responsible for navigating the complex and

charged dynamic of their parents’ relationship. Children reported finding their fathers reactions

to their mothers a fraught and frightening experience. They reported being in positions where

they were unable to speak about their mothers or they were used as messengers, having to pass

on information about changes to future contact arrangements or their mothers lives. Children

were often pulled into an adult role, mediating and negotiating between parents, and the quality

of relationship between parents affected the children’s contact arrangements. The study uses

previous research to support findings and provides clear details of the sample and research

design, which are suitable for the aims and purpose of the study. It also acknowledges the

difficulties of the research interview for children and employs visual prompts and activities to

make the interviews more engaging, with a view to diluting its intensity. However, despite aims

to include views of the children alongside their mothers, it focuses predominantly on stories and

events from the mothers’ accounts, demonstrating a dominance of the adult narrative over the

child’s narratives. This is acknowledged in other divorce literature, where adult views tend to

take precedence (Brand et al., 2017). The study highlights, like Flowerdew & Neale (2003), that

the quality of the relationship between parents is an important factor with regards to impact on

the child. This study also adds an alternative argument to the view that contact with both parents

32

may mediate the negative impacts of parental separation, acknowledging the ongoing relational

consequences of domestic abuse when considering children’s contact arrangements.

Trinder et al., (2002), looked at contact arrangements from the perspective of parents and

children. They aimed to examine how adults and children negotiate and experience contact, and

what makes contact work and not work. The authors, although not explicitly, allude to their

ontology by wanting to identify how each family member experienced the same arrangement and

were not intent on illuminating a ‘true’ account. Trinder et al., (2002) interviewed 140

individuals from 61 families, 57 of which were children. The sample aimed to include both

‘contested’ and ‘uncontested’ contact where half of the families recruited were private ordered

contact arrangements and the other half had a varying degree of involvement form lawyers and

courts. Like other studies in this review the sample included a predominantly white sample, with

an underrepresentation of different ethnicities and ethnic-minorities. Quality and quantity of

contact varied tremendously, with nine different types of contact arrangements being identified,

grouped into three themes; Consensual committed families were committed to regular contact

with low conflict; Faltering families had irregular or ceased contact; and Conflicted families had

disputes about the amount and form of contact.

Trinder et al,. (2002) found that contact places significant demands on both adults and children.

Problems identified by children were parental conflict, relationships with step parents,

establishing meaningful relationships with the contact parent and not being consulted about

contact. The authors show consideration of ethical issues, seeking informed consent, addressing

issues of confidentiality and employing a specialist interviewer to conduct the interviews with

children. However, like Morrison (2015), where adult perspectives have been sought alongside

children, adult voices and perspectives appear to dominate, meaning that children’s voices are

33

not fully heard in the study. The study helpfully addresses practical implications for families and

court services, highlighting the need for a wider range of services (e.g. therapeutic), to be

developed, as well as practical and realistic strategies for managing contact.

Neale and Flowerdew (2007) conducted a long-term study of children’s lives after divorce by

interviewing children at two points in time. The study focused on what it meant for children to

sustain a shared parenting arrangement over a period of time. The focus was on the mechanics

and structure of relationships as well as the quality of them. Neale and Flowerdew (2007) wanted

to move beyond the snapshot approach, to discern how children’s lives were unfolding and to

determine the amount and nature of changes. The study used the same cohort of participants that

were used in Flowerdew & Neale’s (2003) study, following up 60 participants aged 11-17 from

an original study. A new sample of children were also included, who were living in shared

residence arrangements. It is difficult to determine the process by which this study selected its

participants as the sampling strategy is not made clear. The final analysis focuses on 4

participants and again it is not alluded to how this decision was made. Therefore, despite the in-

depth representation of children’s experience it could be questioned why this sample size was

selected. The study takes on a sociological perspective and views children as young citizens who

are entitled to respect and participation. Children were divided between those based in one home

with their residential parent, with varying levels of contact with their non-residential parent and

those living across two homes, i.e. being shared between their parents. The authors wished to

chart what has come to be seen as a relatively conventional arrangement with a more novel and

experimental arrangement that necessitates packing up and moving back and forth every few

days. The study acknowledges that some children may not view themselves as having one home

even though they would be categorized that way for this study and therefore re-categorizes

children in a way that may not fit their subjective experience. This aim appears to be

34

disconnected with the views of the study where the authors see children through the lens of their

citizenship, recognising their need for recognition, respect and participation and respecting their

experiences and agency. Neale & Flowerdew (2007) reported that shared arrangements were

sometimes found to be inflexible and challenging for young people, where young people were

sometimes under emotional pressure to maintain high levels of contact and keep things fair for

their parents. This could lead to the children finding it difficult to exercise their autonomy or

choice. It was discussed that shared residence could work well when it was based on consensus

and good quality relationships and where the needs of the children were a priority and the

arrangement was viewed flexibly. Children in ‘one home’ arrangements demonstrated that

relationships with the out of home parent were sustained when the relationship was valued and

enriching for the young people. When the relationship was challenging contact was likely to

diminish. The study concludes from the four case studies that it is the importance of the

relationship not the mechanics of the relationship that matter when it comes to sustaining contact

in separated families. Good contact is not based on quantity but on good quality relationships.

Inter-parental conflict was found to impact young people’s lives in Fawcett’s (2000) study,

before and after separation. Few adults were able to establish cooperative parenting and contact

was found to not always reflect a quality relationship, as reported by the other studies in this

review (Trinder et al., 2002; Flowerdew & Neale, 2003; Neale & Flowerdew, 2007; Morrison,

2015).

Overall, these studies present the perspectives of children experiencing shared parenting

arrangements and comment that children experience several changes both with their contact with

parents and contextually when their parents separate or divorce. Several different post-divorce or

separation configurations may form, however, it is the general view that it is the quality of the

35

relationships that matter to children and enable a more fluid transition, than the quantity of

contact.

2.5.2(Children’s(Narratives(and(Positioning(

Smart (2006) explores children’s narratives of post-divorce family life to show how children

position themselves in relation to family change, their abilities to be reflexive and the extent they

can generalise from their experience to broader ethical evaluations of family life. The study

recruited 60 participants from an earlier study and appears to use the same cohort of participants

as Neale and Flowerdew (2007) and Flowerdew and Neale (2003). This suggests that the breadth

of experience portrayed in this review is limited and participant views may have been influenced

through their involvement in other studies. All participants were ethnically white and lived in the

north of England and the experience of children from different cultures and background is

missed. The reflexivity of participants is acknowledged by the author who shares that this level

of reflexivity may not have occurred on its own and may have impacted the participants’

positioning and presentation of their narratives. This study also notes the role of the researcher in

the co-production of narratives, acknowledging how the use of questions and vignettes would

have encouraged the children to produce accounts. This mention of reflexivity is brief and the

nature of the study suggests further reflexivity from the researcher could be warranted, including

how the study impacts on the researcher. The study grouped the stories according to the different

structures families took post-divorce and their emotional content. Detail is given of how these

organising principles are arrived at, however, not much else is provided about the methodology.

It was found that children’s stories of post-divorce family life included stories of coping,

surviving and personal growth, through to stories of blame, victimisation, loneliness,

unspeakable pain, confusion and withdrawal. The author suggests that the narratives chosen are

part of constructing a past which helps to shape the kind of person they believe themselves to be.

36

Smart (2006) highlights that these narratives are multilayered, revealing ambivalence and

contradictions. The study also describes how some participants with unhappy accounts were

unable to provide full accounts and had difficulty explaining or elaborating on events, whereas

children who gave contented accounts were able to stand back from their ‘experience of divorce

and position themselves as survivors’. Furthermore, the study found that many of the children

had well developed ethical dispositions on how parents should treat each other, and how they

should behave towards their children indicating they were generalising from their own

experience and connecting their accounts into potentially socially relevant ethical dispositions.

The study is one of a few pieces of research that attempts to capture children’s stories around

their parents’ divorce and speaks to the complexity of their multi-layered accounts, however the

lack of information regarding the methodology and participants makes it difficult to draw valid

conclusions from this research.

2.5.3(Decision(Making(and(Autonomy(

One paper addresses children’s agency within their families and how they influence and actively

contribute to family life (Neale, 2002). Neale (2002) in her study on children’s experiences,