AUGUST 2020

BRIEFING PAPER

HOUSING

Learning from international

housing delivery systems

From

Copenhagen

to Tokyo

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

Acknowledgments

This report is a component of the SPUR Regional Strategy, a vision for the future of the San Francisco Bay Area

spur.org/regionalstrategy

AECOM for SPUR

Authors:

Sarah Karlinsky

Paul Peninger

Cristian Bevington

Thank you to the Core Funders of the SPUR Regional Strategy:

Chan Zuckerberg Initiative

Clarence E. Heller Charitable Foundation

Curtis Infrastructure Initiative

Dignity Health

Facebook

Genentech

George Miller

John S. and James L. Knight Foundation

Marin Community Foundation

Sage Foundation

Silicon Valley Community Foundation

Stanford University

Additional funding provided by AECOM, Fund for the Environment and Urban Life, Microsoft, Seed Fund, Stripe, Uber

Technologies and Wells Fargo.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 1

2. Copenhagen .............................................................................................................................. 3

Key findings ................................................................................................................................................................................ 3

Housing stock overview ........................................................................................................................................................ 4

Policy ............................................................................................................................................................................................. 6

Financing housing .................................................................................................................................................................... 8

Large-scale urban development ........................................................................................................................................ 11

References ................................................................................................................................................................................. 12

3. Berlin .......................................................................................................................................... 13

Key findings ............................................................................................................................................................................... 13

Housing stock overview ....................................................................................................................................................... 14

Policy ............................................................................................................................................................................................ 16

Financing housing ................................................................................................................................................................... 18

References ................................................................................................................................................................................. 19

4. Vienna ...................................................................................................................................... 20

Key findings .............................................................................................................................................................................. 20

Housing stock overview ....................................................................................................................................................... 21

Policy ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 22

Financing housing .................................................................................................................................................................. 23

References ................................................................................................................................................................................ 25

5. Amsterdam ............................................................................................................................. 26

Key findings .............................................................................................................................................................................. 26

Housing stock overview ...................................................................................................................................................... 27

Policy ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 28

Financing housing .................................................................................................................................................................. 30

References ................................................................................................................................................................................. 31

6. Tokyo ........................................................................................................................................ 32

Key findings .............................................................................................................................................................................. 32

Housing stock overview ...................................................................................................................................................... 33

Policy ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 34

Financing housing .................................................................................................................................................................. 35

Large-scale urban development ...................................................................................................................................... 36

References ................................................................................................................................................................................ 37

7. Singapore ................................................................................................................................ 38

Key findings .............................................................................................................................................................................. 38

Housing stock overview ...................................................................................................................................................... 39

Policy .......................................................................................................................................................................................... 40

Financing housing .................................................................................................................................................................. 42

Large-scale urban development ...................................................................................................................................... 43

References ............................................................................................................................................................................... 44

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

1

1. Introduction

As part of the research phase of the SPUR Regional Strategy, AECOM prepared a set of international

case studies of housing delivery with the aim of informing policies to reshape the San Francisco Bay

Area’s housing delivery systems.

The cities included in this document are Copenhagen, Berlin, Vienna, Amsterdam, Tokyo and Singapore.

These cities were chosen for a variety of reasons, including that they compared well to the Bay Area in

terms of demographics, economic composition and housing market characteristics. Although the

political and economic systems are very different in each case, the city case studies presented here all

have a compelling and noteworthy approach to successfully delivering housing, which could inform

future policy innovation in the Bay Area.

The selected case studies demonstrate a breadth of approaches that address both supply and demand

challenges for housing in its entirety, as well as affordable housing more specifically. They draw on a

range of mechanisms, such as regulatory mandates, deregulation and regulatory streamlining, land use

and financial incentives, tenant support and protections, and intergovernmental collaboration.

The case studies included should not be seen as the only interventions each city is undertaking but as

specific elements of each city’s housing toolkit. As the Bay Area looks to update its toolkit, these

mechanisms—along with many others, old and new—can be combined in novel ways to create a more

efficient, integrated and equitable housing delivery system.

Lessons Learned and Best Practices

Although each of the cities profiled in this report has a unique set of policy, regulatory and economic

characteristics, there are some common themes across the cities that can point to new and innovative

policy and governance models for a more effective housing delivery system in the United States broadly

and in the Bay Area specifically. It is worth noting that these case studies were prepared prior to the

COVID-19 pandemic and thus do not take into account new policies for providing housing or income

support to renters and homeowners in these cities. However, two overarching commonalities among

these cities and their housing sectors do position them to respond more quickly and effectively to

housing need in the event of a major crisis like COVID-19:

1. Strong national government leadership in housing. In all of the case studies in this report, the

central government plays a strong role in financing and regulating the housing sector. The

ongoing commitment of these national governments to ensuring a functioning, responsive

housing sector is based on broader societal values around housing being not only an economic

commodity but also a public good.

2. Housing as basic social and economic infrastructure. Much like education or health care,

housing in these cities is treated as a public good and a necessary element of basic economic,

social and public health infrastructure, but it is also a type of traded commodity in a market

economy.

Unfortunately, the Bay Area by itself has a limited ability to drive transformative policy discussions at

the national level about either the role of the federal government or the broader conception of housing

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

2

in U.S. society. But lessons learned from Copenhagen to Singapore could — with great political

leadership and courage — be applied in the region. The most significant of these include the following:

Active city and regional financing and development entities. Copenhagen and Tokyo have created

strong financing and development agencies, which act alongside and in partnership with private

developers, nonprofits and cooperatives to develop infrastructure, leverage the value of government-

owned land assets, and finance and develop new housing.

Streamlined planning and regulatory approvals for housing. Most of the cities profiled in this report

have planning and regulatory systems with less local control and fewer conditional approval processes

than is the case in California and the Bay Area. The most dramatically different approach is in Tokyo,

where landowners and developers enjoy simplified zoning regulations and relatively greater freedom to

develop urban parcels with the residential product types and densities that the market will support.

Greater government involvement in land markets. Many of the case-study cities play an active role in

either acquiring land or regulating land transactions to mitigate the role that land market speculation

plays in driving up housing prices.

Robust tenant protections. Through the creation of rent price indexes (Berlin) or broader tenant rights

and protections (Amsterdam), many of these cities actively support renting and renters as a critical and

valued component of the housing sector.

Nonprofit and cooperative leadership in housing delivery. Compared to most U.S. cities, a greater

percentage of the housing sock in these case-study cities is controlled by nonprofit agencies and

cooperatives, either independent entities or organizations linked to the national or local governments.

Given the already strong nonprofit housing sector in the Bay Area, this model may be something that

could be brought to scale in the Bay Area with greater financial support from state, regional and local

agencies.

In all of the case-study cities, by and large we see greater cross-jurisdictional collaboration and a

stronger sense of regional common purpose than is currently the norm in the Bay Area. But if the

COVID-19 crisis has made one thing clear, it is that political boundaries are largely meaningless in the

face of public health and economic challenges facing this region; if cities and counties work together to

address challenges like COVID-19 and its devasting impact on all housing stakeholders (renters,

homeowners, landlords, developers, investors, etc.), the region will have a much greater chance of

emerging from the crisis with a functioning housing delivery system that can effectively meet the still

great and increasing demand for housing to serve this diverse and growing region.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

3

2. Copenhagen

Key findings

1. The city takes an inclusive approach to providing housing. Relevant policies at the national and

local levels empower residents and tenants to be in control of their own living conditions. As a

result of both cultural norms and policy support, housing is seen less as a commodity to be bought

and sold and more as an essential element that all residents should have access to in a successful

and globally competitive city.

2. There is a development corporation that is politically independent. A development corporation

formed by the city or national government operates outside of political cycles, enabling long-term

strategic decisions regarding infrastructure and development. The corporation’s role in providing

critical infrastructure also encourages new development and allows the corporation (and city) to

benefit from the land value increases.

3. Funding is recycled. A one-time investment establishes the initial funds, which are then maintained

through repayment agreements, in particular compulsory contributions after the initial mortgages

have been paid off. The funds are replenished and can grow to allow for future development.

4. Financial requirements apply to housing association management. Under these requirements,

compulsory contributions from tenants cover the cost of loan repayments and the management of

housing developments. In addition, housing associations must have reserve funds specifically for

maintenance, renovation and construction. These requirements ensure that housing associations

are financially equipped to maintain quality.

5. The city uses a combined public asset portfolio. Combining all public assets in a single portfolio

allows the city both to identify land and assets for housing and to use the portfolio’s combined

value as collateral for financing large-scale development.

6. National and city government form partnerships. Strong relationships between different levels of

government support large-scale development by pooling resources, political clout and capacity.

This kind of partnership enabled Copenhagen to establish its development corporation and to

include Copenhagen’s port site in the city’s asset portfolio, spurring significant development in the

city by making it easier to set aside land and pay for development.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

4

Housing stock overview

In order to demonstrate Copenhagen’s unique approach to providing housing, this report compares the

city proper to the wider region. Even at this local scale, real differences can be seen. Within the city,

most housing units are provided through cooperatives, but in the wider region, the predominant

housing type is an owner-occupied unit. The majority of owner-occupied units within Copenhagen are

flats/apartments versus single-family houses in the wider region.

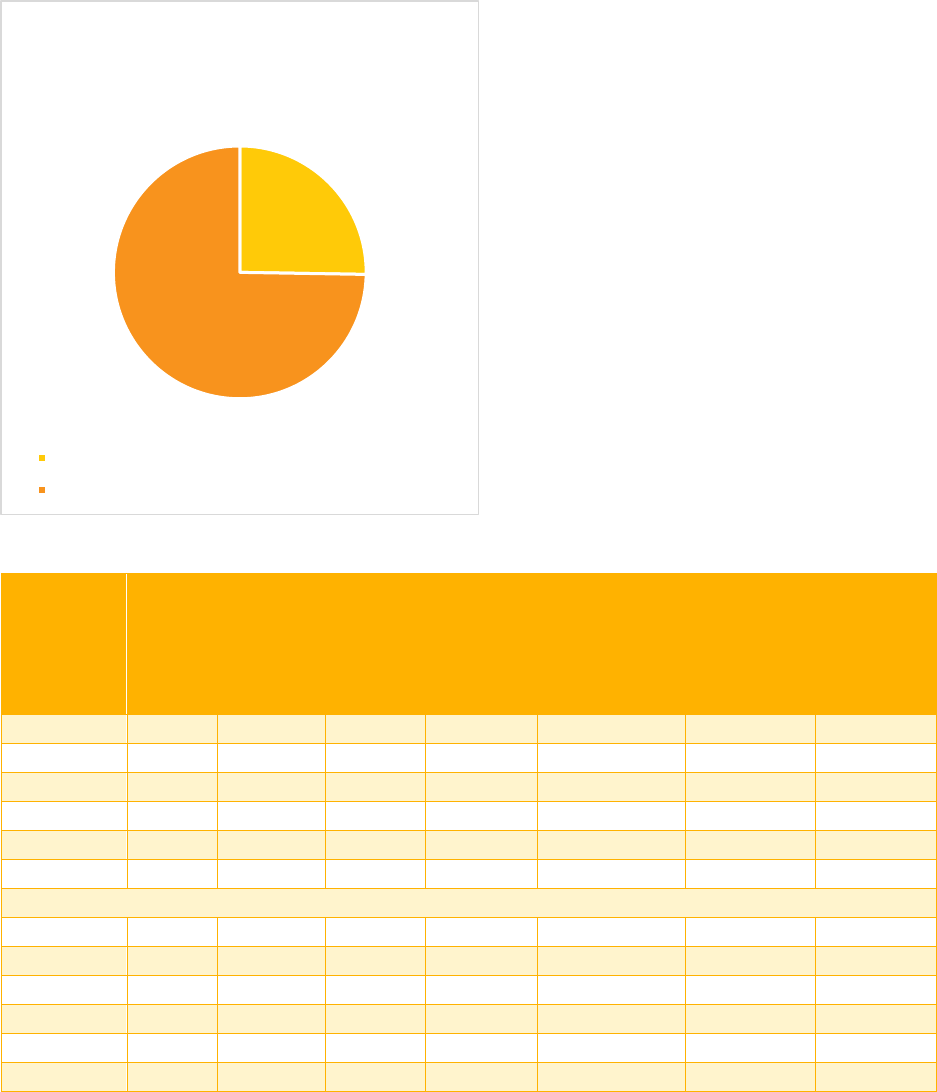

Dwellings in the Capital Region and the City of Copenhagen by Type

Housing type

Number of dwellings

Percent of total housing market

Region

Copenhagen

Region

Copenhagen

Owner-occupied

family houses

209,000

18,000

24

5

Owner-occupied

flats

127,000

70,000

15

20

Cooperatives

135,000

112,000

15

31

Social housing

189,000

57,000

22

16

Private rentals

175,000

77,000

20

21

Other rentals

38,000

24,000

4

7

Total

874,000

357,000

100

100

Source: Building and Housing Register (BBR), March 2011

24%

15%

15%

22%

20%

4%

Housing Type,

Region (%)

Owner-occupied family

houses

Owner-occupied flats

Cooperatives

Social housing

Private rentals

5%

20%

31%

16%

21%

7%

Housing Type,

Copenhagen (%)

Owner-occupied family houses

Owner-occupied flats

Cooperatives

Social housing

Private rentals

Other rentals

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

5

Dwellings by Ownership Type

Ownership

Number of dwellings

Percent of total housing market

Region

Copenhagen

Region

Copenhagen

Owner-occupied

(individuals, including

partnerships)

440,567

92,653

47.5

28.8

Nonprofit building

societies

211,095

62,440

22.8

19.4

Limited liability

companies

75,524

40,393

8.1

12.5

Cooperatives

139,770

99,286

15.1

30.8

Public authorities

17,790

4,646

1.9

1.4

Other or unknown

42,838

22,470

4.6

7.0

Total

927,584

321,888

100

100

Source : StatBank Denmark, http://www.statbank.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=1536

47.5

22.8

8.1

15.1

1.9

4.6

Building Ownership

Type, Region (%)

Owner-occupied (individuals, including

partnerships)

Nonprofit building societies

Limited liability companies

Cooperatives

Public authorities

Other or unknown

28.8

19.4

12.5

30.8

1.4

7

Building Ownership

Type, Copenhagen (%)

Owner-occupied (individuals, including

partnerships)

Nonprofit building societies

Limited liability companies

Cooperatives

Public authorities

Other or unknown

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

6

Policy

Land use

City and local governments in Denmark (including Copenhagen) can make decisions regarding building

permission and land zoning, as well as act as the urban developer. For example, in order to support the

development of housing and commercial activities, the city has rezoned publicly owned land to

residential and commercial and then transferred these asses to the Copenhagen City and Port

Development Corporation (see later sections for more information) to allow the implementation of

critical enabling infrastructure.

The city also establishes detailed regulatory plans intended to control land use and set density and

building envelope requirements, ensuring that high-quality development occurs across the city.

Importantly, these requirements are not intended to hinder creativity or innovation but to enable them

in a manner that enhances the city.

Affordable housing

Denmark’s national policy seeks to provide “affordable housing for all” as well as allow people to

influence their own living conditions. In recent years, this policy stance has focused particularly on the

elderly and other specific segments of society that are most in need. The housing subsidies reflect this,

with subsidies that enable individual households to enter and remain secure in the housing market,

rather than just subsidies for construction.

Tenant protections

All housing types except owner-occupied dwellings are subject to rent regulations, in particular units in

housing associations. However, this approach has been attributed to reduced investment in the sector.

National and local governments in Denmark provide housing allowances to those residents in need.

Such benefits are based on household income and size.

Social housing -- publicly financed housing that serves low, moderate and middle-income households -

is largely made up of older developments, which are often located in inner-city estates. Unlike in many

developed cities, these older developments are widely considered to be of better quality than other

rental housing, which can be linked to the funding and financing approaches in place, as outlined in the

sections that follow.

Each housing estate is required to be financially stable, with its individual books balanced. Separate

estates, including those operated by the same housing association, are advised not to seek cross-

subsidization between estates, meaning that cashflow from one estate should not be used to subsidize

deficits in another estate.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

7

Tenant representation on estate management boards and housing association boards ensures a sense of

ownership and embeds residents in decision-making processes.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

8

Financing housing

The National Building Fund for Social Housing

The fund aims to channel profits made from social housing into ensuring the security of future housing,

as well as to maintain and manage existing stock. Established in 1967, the fund provides both financial

support and technical assistance to social housing associations.

Financing comes from compulsory contributions by tenants of estates established before 1970 as well

as from mortgage payments by tenants. Payments from tenants that were initially used to cover the

mortgage repayments continue after the mortgage has been repaid.

Contributions equal about $120 million (DKK 827 million per annum, 2011). Annual contributions are

adjusted to reflect changes in the Danish regulatory index for housing construction.

For developments that were financed before 1999, two-thirds of the liquid assets earned after the

mortgage has been repaid are transferred to the national fund, with the remaining one-third going to

the local Disposition Fund of the relevant housing association/organization. For developments financed

from 1999 onward, one-third of the total liquid assets is sent to the national fund, with two-thirds kept

by the local Disposition Fund.

Assets that have been transferred to the national fund are split, with half going to the Central

Disposition Fund and the remaining half deposited in the New Housing Construction Fund.

It is expected that the payments received from the repaid loans and deposited into the National

Building Fund will rapidly increase, from $50 million (DKK 343 million) in 2008 to $370 million (DKK

2,520 million) in 2020.

Housing associations have the right to use two-thirds of the compulsory contributions that they receive

for new construction and rehabilitation, maintenance and modernization of existing housing stock in the

estate from which the contributions were drawn, via the Central Disposition Fund

Central Disposition Fund

The fund is used in multiple ways:

• Grant payments for renovation, refurbishment and maintenance works

• Support to socially vulnerable areas now and in the future (this can take many forms but does

include rent subsidization and must be approved by the local municipality and community)

• Demolition grants

• Infrastructure upgrades

• Operational expenses where there are financial struggles and/or deficits

• New construction grants

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

9

New Housing Construction Fund

This fund draws funding from developments financed after December 31, 1998 (as detailed above). The

sources of funding include both profits gained from tenant contributions and the transfer of liquid

assets upon completion of the mortgage term (35 years). The fund is used for the construction of new

housing.

Other subsidies and incentives

Social housing is also subsidized by the central government through the copayment of mortgages

aimed to assist with the financing of new housing construction.

Subsidies are also offered through urban renewal programs, as well as direct contributions to capital

costs.

Tenant contributions in social housing are determined by cost recovery principles rather than seeking to

generate additional profit for the developer, meaning that payments made by the tenants should cover

the cost of development (based on mortgage rates) and of maintenance and management of the

property.

Social housing is exempt from national income and real estate taxes.

Cooperatives

Denmark, and in particular Copenhagen, supports a cooperative approach to providing both housing

association units and private housing. This approach has become a widely accepted part of the Danish

housing market. Though both models below are considered cooperatives, there are distinct differences.

• Private nonprofit housing associations

─ Residents have collective ownership over properties and control over the association. They

make up the majority of the individual estate management boards and have strong

representation on the overall housing association boards. While they are still considered

tenants of the association, residents have significant control and decision-making powers

compared to other models.

• Private cooperatives

─ Individual residents hold shares in the common property and communal areas and have usage

rights to their flats.

─ Since 2005, residents have been permitted to take out loans using cooperative apartments as

collateral.

─ Cooperatives have overtaken rental units as the major provider of housing, which can be

attributed to changes in legislation in the 1970s. The law stipulates that private landlords give

tenants the opportunity to form a cooperative and take over the property before private

resale. The formation of cooperatives is supported by state credit guarantees and tax

exemptions.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

10

Copenhagen City and Port Development Corporation

Land that has been developed by the Copenhagen City and Port Development Corporation (CCPDC) is

sold at a heavily discounted price to facilitate the development of social housing.

The CCPDC helps to link developers and social housing associations/organizations, which facilitates the

transfer of the properties to social housing providers when development is complete.

For further details on CCPDC, see the “Large-scale urban development” section below.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

11

Large-scale urban development

Copenhagen City and Port Development Corporation

Copenhagen has a history of using specially established corporations to deliver infrastructure. For

example, Orestad Development Corporation helped to build the metro system and was a founding

component of the CCPDC.

Established in 2007 as a co-owned corporation between the city (55% ownership) and national

government (45% ownership), CCPDC has evolved toward greater city ownership (95%), with only 5%

now owned by the national government. This shift gives the city greater autonomy to make decisions

and plan strategically for its future.

When the corporation was formed, a comprehensive assessment of public assets and land was carried

out, including an assessment of market value (which is used as collateral for loans). To aid decision-

making processes, publicly owned assets were bundled together in a single portfolio.

To ensure that CCPDC can take long-term strategic views on development, the corporation is insulated

from politics, which also allows it to be agile and to respond appropriately to changing market

conditions.

CCPDC primarily funds infrastructure, such as public transit, roads, recreation and other public amenities

that support and facilitate urban development. Since its formation, the corporation has undertaken

around 50% of all redevelopment in Copenhagen.

The corporation is now funded through the sale and lease of public land and assets after infrastructure

projects have been carried out, allowing land value increases to be captured and reinvested to fund

future infrastructure delivery.

CCPDC can borrow against the value of public assets while also benefiting from low-interest loans that

result from the city’s AAA credit rating.

The corporation does not operate in isolation but instead forms partnerships with both private and

public urban development entities.

The harbor/port land, which was originally owned by the national government, was transferred to the

corporation to allow the corporation to leverage land and development value to deliver $2 billion in

metro transit investments. As a result of the corporation’s initial investment in the metro a further $495

million investment was successfully secured from other sources.

The North Harbor redevelopment alone has led to $15 billion in reinvestments.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

12

References

Building and Housing Register (BBR), March 2011 - Sasha Tsenkova and Hedvig Vestergaard, Social

Housing Provision in Copenhagen, University of Calgary,

https://www.enhr.net/documents/2011%20France/WS07/Paper-Tsenkova-WS07.pdf

BL—Danish Social Housing, “The Danish Social Housing Sector,” 2018, https://www.bl.dk/in-english/

Bruce Katz and Luise Noring, The Copenhagen City and Port Development Corporation: A Model for

Regenerating Cities, Brookings Institution, 2017, https://www.brookings.edu/wp-

content/uploads/2017/05/csi_20170601_copenhagen_port_paper.pdf

“Copenhagen in Brief,” Copenhagen.com, 2020, https://www.copenhagen.com/in-brief

Council of Europe, “Copenhagen, Denmark—Intercultural City,”

https://www.coe.int/en/web/interculturalcities/copenhagen

Eric Clark et al., Financialisation of Built Environments in Stockholm, Copenhagen, and Ankara: Housing Policy and

Cooperative Housing, FESSUD Working Paper No. 167, 2016,

http://portal.research.lu.se/portal/files/26593771/16_FESSUD_WPS_167.pdf

Landsbyggefonden, “The Danish Social Housing Sector,” https://lbf.dk/om-lbf/english/

Sasha Tsenkova and Hedvig Vestergaard, Social Housing Provision in Copenhagen, 2011,

https://www.enhr.net/documents/2011%20France/WS07/Paper-Tsenkova-WS07.pdf

Statbank Denmark, http://www.statbank.dk/statbank5a/default.asp?w=1536

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

13

3. Berlin

Key findings

1. Renting is supported as a long-term approach to housing. Berlin, and Germany as a whole, has

long been a place where renting a home is broadly accepted as a long-term housing option. Rental

housing is the most common type of housing in Berlin. Strong tenant protections allow renters to

feel secure in their homes, as opposed to the short-term lease agreements common in other parts

of the world.

2. Housing is viewed less as a commodity to buy and sell than as an essential right. Historically,

housing in Berlin has been disconnected from speculative investment markets, and for the most

part it still is. The local culture—which sees housing as something everyone should have access to,

not as a vehicle for personal wealth—has helped to maintain affordable housing across the city until

recent years.

3. A rental price index prevents excessive increases. Landlords are discouraged from increasing

rents by levels deemed to be excessive, and tenants are equally discouraged from paying excessive

amounts for rental properties as determined by a voluntary index, meaning that the index operates

mainly as a moral code for both landlords and renters, with legal backing only provided to settle

disputes.

4. Municipal governments have strong powers to purchase property before private developers.

With a right of first refusal on property sales within municipal government boundaries, local

governments can seek to ensure that sites that would otherwise be purchased and redeveloped

into high-end properties remain affordable and meet the needs of the existing population. In many

cases, the municipalities have a long history of exercising this right.

5. There are long-standing municipal affordable housing providers. Municipal affordable housing

providers have long histories and a strong presence in the city. They are supported across all levels

of government, allowing them to operate effectively even in increasingly competitive property

markets.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

14

Housing stock overview

Unlike many cities around the world, Berlin has a preponderance of rental housing (84.9% of total units).

A combination of private landlords, cooperatives and government entities supplies these rental units.

Only 15.1% of housing units were classified as owner-occupied in 2017.

Berlin is also in a relatively unique situation, because much of its affordable housing is naturally

occurring (meaning that it does not require subsidies). Just 10.8% of total units are subsidized. Most

units are supplied by regular providers (68.8%), with affordable housing providers responsible for 31.2%

of all units in the city. This structure, however, puts the city at risk from market fluctuations as it

becomes a more desirable place to live.

Housing type

Percent of total housing

market

Number of dwellings

Rentals

84.9

1,626,500

Private rentals

59.7

1,144,640

Municipal housing

15.4

294,725

Cooperatives

9.8

187,135

Owner-occupied

15.1

290,000

Total

100

1,916,500

59.7

15.4

9.8

15.1

Housing Type (%)

Private rentals Municipal housing

Cooperatives Owner-occupied

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

15

Provider

Number of

dwellings

Percent of

category

Percent of total

housing market

Subsidized

Rentals

Private rentals

90,243

43.5

4.7

Municipal housing

94,098

45.3

4.9

Cooperatives

23,175

11.2

1.2

Total

207,516

100

10.8

Unsubsidized

Rentals

Private rentals

1,054,397

61.7

55

Municipal housing

200,627

11.7

10.5

Cooperatives

163,958

9.6

8.6

Owner-occupied

290,000

17

15.1

Total

1,708,984

100

89.2

Total dwellings

1,916,500

Provider

Number of

dwellings

Percent of

category

Percent of total

housing market

Affordable providers

Rentals

Private rentals

114,915

19.2

6

Municipal housing

294,725

49.4

15.4

Cooperatives

187,135

31.4

9.8

Total

596,775

100

31.2

Other providers

Rentals

Private rentals

1,029,725

78

53.7

Owner-occupied

290,000

22

15.1

Total

1,319,725

100

68.8

Total dwellings

1,916,500

Source: Housing Market Report, Investitionsbank Berlin, 2017

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

16

Policy

Rent index (Mietspeigel)

The index is updated and published every two years so that both landlords and tenants can use it to

compare prices for similar properties. The index prices apply to both existing lease agreements and new

leases. Landlords are permitted to increase the price of rent to the level indicated in the index. While

this rule is not legally binding, it can be used as part of legal proceedings in dispute cases.

Rent break (Mietpreisbremse)

A national tool that can be adopted at the state level, this mechanism is intended to control rent

increases in private contracts. Adopted in Berlin in 2015, the policy limits the increase for new leases to

10% above the index price for the applicable type of unit. However, the regulation only applies to

buildings constructed before 2014 and can only be used for up to five years. It also doesn’t apply in

cases of modernization (see below). Once again, this law is only enforced in situations where a landlord

or tenant brings legal action.

Modernization

In many cases, rent increases are heavily controlled. However, when extensive building improvements

have been made, the landlord can negotiate much higher increases. In a hot property market such as

Berlin, this allowance has resulted in rent increases of about 40% to 50%, with occasional reported

increases of 200%. To discourage such large increases, the municipality can step in with its right of first

refusal (see below).

First refusal

When a building is put up for sale within a municipality’s boundary (a municipality, in this case, is one

level below the city of Berlin’s government), the municipality has the right of first refusal to purchase

that property. This right is not exercised in most instances, but one municipality, Friedrichshain-

Kruezberg, frequently uses it. The municipality purchases the properties and often retains them as

affordable housing via its own municipal housing company.

In some cases, in particular with modernization projects where the intent to increase rents is clear, the

municipality will negotiate with the developer or landlord to prevent increases from happening—for

example, by instituting a lock-in period in which significant rent increases will not occur over an agreed-

upon time frame. The municipality has two months to agree to this approach, but ultimately a municipal

government could enact its right of first refusal to purchase the project if an agreement is not reached.

The use of this right can cause tension between municipalities and the Berlin city government when

there is a conflict of interest. In some cases, the right of first refusal has been overruled.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

17

European Union and European Commission: Target groups

As with all countries that form the European Union, Germany (and therefore Berlin) is subject to

European Commission directives. However, Germany has opted not to accept the commission’s “target

groups” approach to affordable housing allocation (see the Amsterdam case study for more information

regarding target groups). Germany determined that this approach would have negative impacts on the

country’s — and developers’ — ability to create socially mixed communities that have sufficient stability

to become long-term parts of the urban fabric.

Social housing

Across all providers of social housing — municipal housing companies and the private sector — tenants

must meet income requirements to qualify. Income levels are primarily set at the national level, but with

room for some local variation to reflect specific housing markets. For Berlin, the household income limits

have been set at:

• $18,500 (¤16,800) for single-person households

• $27,800 (¤25,200) for two-person households

• $6,300 (¤5,740) for each additional household member

• An additional $800 (¤700) per child

Means testing was introduced in 2015 to reflect the changes in the Berlin housing market in recent years

and to ensure that those most in need are able to access necessary housing. Approximately 250,000

residents in 125,000 units benefit from this policy. Both existing properties under the ownership of the

state and future state projects must set aside 55% of units for low-income households.

Housing cooperatives

As with the cooperative model found in Copenhagen, tenants in cooperative units have more rights than

a standard rental property agreement would allow and can play a role in the decision-making and

management of the cooperative. Lease agreements are perpetual, which provides long-term security

but also results in long wait lists and competitive applications when spaces do become available.

Turnover in cooperative units is extremely low.

Each cooperative is entitled to set its own application requirements and contract lengths, with

preference often given to those with middle to upper incomes in order to ensure a more stable financial

arrangement for all members of the cooperative.

In some cases, the cooperatives can also act as savings banks and neighborhood resource centers.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

18

Financing housing

Federal funding

The federal government allocates funds to the individual states, but how this funding is distributed

within each state is left largely to the state government to determine. Housing is one of the primary uses

of federal funding. In Berlin, funding allocated to housing is largely used for subsidies that incentivize

landlords and developers to provide affordable housing.

Subsidies

As previously mentioned, Berlin allocates part of its federal funding toward housing subsidies for

landlords and developers, in the form of public loans. In the city, many providers manage a mix of social

(affordable) and market-rate units, and Berlin does not prioritize one provider over another. But when a

property owner takes out a subsidized loan against a property, the funds must be used for social

housing. All units that are part of the development for which the loan is used are then considered to be

social units and are subject to lock-in periods which protect current tenants from rent increases for an

agreed upon length of time.

The scheme was originally introduced in the 1960s and ran till the 1990s, before being reintroduced in

2014. During the period when subsidies were abolished, the housing market was so depressed in Berlin

that units provided through this system were often more expensive than market-rate units. Many of the

original lock-in periods have expired or are about to, which means that landlords can now charge

market rates. Those landlords and developers seeking a loan post-2014 will often be subject to longer

lock-in periods (up to 30 years). Municipal housing companies that access subsidies must designate at

least 50% of units as social housing across their portfolios.

Municipal housing companies

Municipal housing companies in Berlin are obligated to provide social housing for low-income

households that would otherwise not be able to access the private rental or owner-occupied markets.

Many of these companies have long histories in the city dating back to the 1920s, when they were

established to respond to the severe economic decline after World War I. Their aim has always been to

ensure that those who needed it could access safe, high-quality and healthy housing. The companies are

technically private companies, but they are wholly owned by the state of Berlin. Through a blend of

social and market-rate housing, the companies are run to turn a profit, but the profits generated are

then fed back into the Berlin state treasury to be reinvested in the city’s housing stock.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

19

References

Erik Kirshbaum, “‘Poor but Sexy’ Berlin Now Home to Soaring Rents and Rising Tensions,” Los Angeles

Times, April 24, 2018, http://www.latimes.com/world/europe/la-fg-germany-berlin-property-20180424-

story.html

Feargus O’Sullivan, “Berlin Just Showed the World How to Keep Housing Affordable,” CityLab, Nov. 12,

2015, https://www.citylab.com/equity/2015/11/berlin-just-showed-the-world-how-to-keep-housing-

affordable/415662/

Feargus O’Sullivan, “Can Berlin Buy Its Way out of a Housing Crisis?,” CityLab, Jan. 2, 2018,

https://www.citylab.com/equity/2018/01/friedrichshain-kreuzberg-apartments-rent-prices/549314/

Investitionsbank Berlin, Housing Market Report, 2017

https://www.ibb.de/media/dokumente/publikationen/in-english/ibb-housing-market-

report/ibb_housing_market_report_2017_summary.pdf

Maarten van Brederode, Affordable Rental Housing in Amsterdam and Berlin: A Comparison of Two European

Capital Cities, University of Amsterdam master’s thesis, June 11, 2018,

http://www.afwc.nl/fileadmin/user_upload/Bestanden_2018/THESIS_Maarten_van_Brederode_FINAL.P

DF

Patrick Collinson, “Berlin Tops the World as City With the Fastest Rising Property Prices,” The Guardian,

April 10, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/apr/10/berlin-world-fastest-rising-property-

prices

Statistisches Bundesamt (Destatis), “Income, Consumption, and Living Conditions,” 2020,

https://www.destatis.de/EN/FactsFigures/SocietyState/IncomeConsumptionLivingConditions/IncomeC

onsumptionLivingConditions.html

“Why Is Berlin So Dysfunctional?,” The Economist, Dec. 2, 2017,

https://www.economist.com/europe/2017/12/02/why-is-berlin-so-dysfunctional

https://www.ihk-

berlin.de/blueprint/servlet/resource/blob/3178106/8435c9f495d401cf57c9109e458e8580/berlin-s-

economy-in-figures-2015-1--data.pdf

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

20

4. Vienna

Key findings

1. Renting is supported as a long-term approach to housing. As in Berlin, renting is fully accepted as

a long-term living option and is protected by the city. The most common type of housing in Vienna,

rental units are largely provided by the city itself or at least subsidized by the government.

2. Land use and planning focuses on community development. The planning system in Vienna

supports and enhances both new development and existing communities through integrated and

community-led approaches.

3. The city is a major and trusted housing provider in the city. Not only is the city a major owner and

operator of housing in Vienna, it is also a trusted source of housing. Living in a city-provided or

city-subsidized home is considered a desirable form of housing. These high-quality units are

integrated within the city fabric.

4. Housing is primarily a place to live, not a commodity to buy and sell. As in Berlin, housing is

disconnected from speculative investment markets; however, Vienna takes this a step further by

restricting private developers’ ability to generate large profit margins through redevelopment.

Housing is not viewed as a means to increase personal wealth, but rather as an essential part of life

that everyone should have access to.

5. National and city governments collaborate. Both levels of government contribute to affordable

housing funding and subsidies, reinforcing the ethos that everyone should be able to afford a

home. In Vienna, the national government contributes a greater proportion that the city

government does.

6. Employees and employers contribute to subsidized housing. Through specific and transparent

taxation, employees and employers make direct contributions to affordable housing in Vienna and

in Austria as a whole. Linking this individual contribution to federal taxes supports the mentality

that it is a civil responsibility to support housing. The national government distributes the funds,

ensuring a fair share to those areas that need the most support.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

21

Housing stock overview

In Vienna, the majority of units are rental properties, but unlike in many cities, the vast majority of these

units are some form of affordable housing. In fact, 48.1% of all housing units in the city are considered to

be social housing. Owner-occupied and single-family homes make up just 22.8% of units in the city.

Housing type

Percent of

total housing

market

Rentals

77.2

Private rentals

29.1

Total social rentals

48.1

City operated social

housing

24.2

Nonprofit housing

23.9

Owner-occupied and other

22.8

29.1

24.2

23.9

22.8

Housing Type (%)

Private rentals

City operated social housing

Nonprofit housing

Owner-occupied and other

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

22

Policy

Land use

Vienna has specific policies in place to ensure that new developments are designed to create and

enhance communities, with longevity at their core. This goal is particularly important in social housing

projects, which are located in low-rise but high-density developments. These developments are

encouraged to reinvest in existing communities and neighborhoods. The city gives preference to

projects that include “care functions” for key groups, such as the elderly or disabled, and favors rental

units over homeownership in new housing developments.

The city has also instated the “wohnbauoffensive,” which aims to remove current barriers to permitting

and construction activities and boost housing production by 30%.

Housing rehabilitation and renovation

When properties in the city are rehabilitated or renovated, it does not result in increased rent for

tenants. Strong tenant protections are supported by local community interest group and community

social support worker representation in all social housing projects, ensuring community backing to

ensure the tenants best interests are protected.

Housing research

The city currently runs the largest housing research program in Europe, which helps to ensure high-

quality housing that meets the needs of Vienna residents.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

23

Financing housing

Federal taxes

A portion of Austrian federal taxes subsidizes social housing. This tax is roughly 1% of net income and

consists of an equal share of employee and employer contributions. In Vienna, the amount collected is

approximately ¤450 million per year, which is then matched with a ¤150 million contribution from the

Vienna state budget. The financing arrangements are guaranteed until 2020, when they will be

reevaluated.

This money is used as a subsidy for the construction, renovation, rehabilitation and preservation costs of

social housing stock. Of the ¤600 million, the split is:

• ¤100 million for housing allowances

• ¤500 million for investment (two-thirds for the construction of new units and one-third for

rehabilitation and renovation)

Vienna Housing Fund

A city-owned nonprofit, this fund operates with complete independence from the city’s political

workings and election cycles. The fund was established with ¤45 million of publicly owned land from the

city and has remained self-sufficient since its inception.

With its ability to buy and sell property on the open market, the fund generates 7,000 to 13,000 new

units annually. It maintains a two-year supply of land to ensure that it’s not impacted by the short-term

fluctuations of the property market.

The scale of activity of the Vienna Housing Fund and the city’s housing associations is so significant that

these entities actually influence the overall housing market in the city.

City-provided housing

In contrast to many cities in Europe and around the world, Vienna did not dispose of its publicly owned

housing during postwar times but instead established a strategy to maintain ownership and to

rehabilitate the units. Today, the city is a major housing provider, with approximately 220,000 units

under its control. It is also often seen as the first point of contact for those looking to dispose of land or

property.

Subsidies

Subsidies are provided in the form of low-interest, long-term public loans to developers. The repayment

of the loans goes into a revolving fund that provides loans to new developers and landlords. Generally

speaking, approximately one-third of construction costs can be covered by this type of loan. As a result,

around 80% of all new builds in the city use this subsidy scheme in some way.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

24

In order to access such a loan, the developer or landlord must demonstrate that the development being

proposed fulfills prescribed design and quality criteria. Applications for subsidies or even bids to

purchase city-owned land can be made in various ways, including through design competitions in which

the winner receives the subsidy or land, helping the city ensure the design quality of new builds.

Vienna operates supply-side subsidies to encourage housing development across the city rather than

demand-side subsidies (to tenants). There are no indirect subsidies, such as tax reductions, for those

investing in affordable property; this policy prevents higher-income groups from benefitting from such

developments.

Private developer contributions

Private developers that wish to participate in the Vienna housing market must return profits generated

from housing development to a revolving fund, which is used to fund other housing projects the city

operates.

Specialty housing banks

Financial institutes have been set up specifically to offer funding and financing arrangements to

developers, landlords and homeowners to build and purchase property. These institutes receive tax

breaks.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

25

References

Adam Forrest, “Vienna’s Affordable Housing Paradise,” Huffington Post, July 19, 2018,

https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/vienna-affordable-housing-

paradise_us_5b4e0b12e4b0b15aba88c7b0

City of Vienna, “Demographic Information 2019,”

https://www.wien.gv.at/english/administration/statistics/population.html

Hope Daley, “Vienna Leads Globally in Affordable Housing and Quality of Life,” Archinet, July 25, 2018,

https://archinect.com/news/article/150074889/vienna-leads-globally-in-affordable-housing-and-

quality-of-life

Joe Cortright, “Housing Policy Lessons from Vienna: Part I,” City Observatory, July 20, 2017,

http://cityobservatory.org/housing-policy-lessons-from-vienna-part-i/

Michael Fitzpatrick, “What Could Vienna’s Low-Cost Housing Policy Teach the U.K.?,” The Guardian, Dec.

12, 2017, https://www.theguardian.com/society/2017/dec/12/vienna-housing-policy-uk-rent-controls

Wolfgang Forster, “Vienna: Sustainable Housing for a Growing Metropolis,” Feb. 27, 2018,

https://www.nesc.ie/assets/files/Forster.pdf

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

26

5. Amsterdam

Key findings

1. Housing associations have a strong presence. The significant use of housing associations means

that much of the housing stock is subsidized in some form and is subject to rules and regulations

around price, accessibility and quality.

2. There are strong planning policies. Through robust land use policies, the city ensures that new

development and redevelopment projects meet policy requirements, that existing communities are

protected and that new communities are integrated.

3. The city owns a significant amount of housing. Because the city of Amsterdam owns and operates

a large stock of properties, it can exercise a lot of control over providing housing to residents and

can set prices that are less vulnerable to external market forces.

4. Rents are controlled. The city (and the Netherlands as a whole) supports the culture of renting by

restricting the amount that rent can be raised per year. Rent control protects renters from rapid

increases, which can force vulnerable communities to move.

5. Prices for housing are point-based. Meant to reduce market influence over housing, the point-

based system (see “Financing housing” below) aims to ensure that the price reflects the true value

of the unit as a home rather than as an economic commodity. Note that the price/market value has

now been included in this system, which will have some impact on the effectiveness of this

approach to providing affordable units (but market value is just one of several criteria).

6. Strong tenant rights and protections are in place. Along with rent control, tenant rights create a

culture favorable to tenants, supporting affordable renting as a viable long-term option for

housing. These protections also promote the development of community by allowing people to

plan for the long term in a property rather than seeing it as a temporary stopgap or an unstable

situation.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

27

Housing stock overview

The majority of housing units in Amsterdam (52.6%) are in some way regulated. The single largest

category, units regulated by a housing association, makes up 39.4% of the total units in Amsterdam,

though it should be noted that not all housing association housing is regulated as outlined in the table

below. Owner-occupied units account for 32.5% of all units in the city. Though not as much as Berlin and

Vienna, Amsterdam does provide a significant proportion of its housing through the private rental

market (both regulated and unregulated) at 24.4%.

Housing type

Number of dwellings

Percent of total

housing market

Total dwellings

427,900

100

Housing associations

184,300

43.1

Private rentals

104,300

24.4

Owner-occupied

139,300

32.5

Provider

Number of

dwellings

Percent of

category

Percent of total

housing market

Regulated

Rentals

Housing

associations

168,700

74.9

39.4

Private rentals

56,600

25.1

13.2

Total regulated

225,300

100

52.6

Unregulated

Rentals

Housing

associations

15,600

7.7

3.7

Private rentals

47,700

23.5

11.2

Owner-occupied

139,300

68.8

32.5

Total unregulated

202,600

100

47.4

Total dwellings

427,900

43.1

24.4

32.5

Housing Type (%)

Housing associations Private rentals

Owner-occupied

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

28

Policy

Land use

City planning and land use policies seek to create and maintain mixed communities that have both a

demographic mix and a mix of uses. The Dutch/Amsterdam planning system is generally considered to

be flexible and agile enough to respond to issues and effectively learn from past errors.

Housing Act of 2015 (target groups)

In line with EU/European Commission regulations, new housing policy was introduced in the

Netherlands to ensure that housing provided by housing associations was reserved for those deemed to

need it the most (“target groups”). As a result of this update, 90% of new housing association contracts

are given to households considered to be socially disadvantaged (earning no more than ¤33,000).

Housing associations must comply with this regulation to continue accessing state aid through loan

guarantees, among other things. The associations are permitted to rent up to 10% of the remaining units

to households with incomes up to ¤40,349.

Social housing

Units considered to be social housing make up the majority of affordable rental properties in the city.

This approach stems from the rise of the welfare state and has become an integral part of life in the

Netherlands, as in many northern European and Scandinavian countries. The city of Amsterdam still

owns a significant proportion of the city’s housing stock, though this is decreasing.

The income limit for social housing is ¤36,165, though this does not take into consideration any potential

variations in household makeup (size, number of children, etc.). The income limit for regulated units

provided by private landlords is ¤44,360.

All limits (including those set by the 2015 Housing Act) only apply to new contracts. In the Netherlands,

residential contracts are generally given for an indefinite period of time and are not terminated based

on any increases in income over the previous limits. Therefore, once tenants secure a unit, their tenancy

can in many cases be considered to be secure regardless of future circumstances.

In 2016, new contracts for young people (up to age 28) were introduced. These temporary, five-year

agreements support those entering the city’s job market, particularly in more junior roles. Since these

younger people will likely see income increases by the end of the five-year period, this system uses a

stepping-stone approach that helps young workers while also ensuring a rotating supply of more

affordable units.

Because contracts are long and tenant protections are strong, there are long waiting lists for affordable

units, reported to be up to 14 years.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

29

There are also nationally set limits for the amount that can be charged for affordable units. In 2018, the

maximum allowable rent was ¤710.68 per month, which remains fixed for three years.

Amsterdamse Federatie van Woningcorporaties (AFWC)

The AFWC is a voluntary organization that aims to provide a platform for knowledge-sharing about

providing high-quality, affordable housing in Amsterdam. All housing associations signed on to the

ethos of the “undivided city” and agreed to collaborate. The AFWC is also supported by a strong

tenants’ association to ensure that tenants’ views are represented and that key stakeholders in the

market can have a balanced dialogue. Two of the AFWC’s core agenda items are making housing

affordable and increasing the level of construction in the city, with a set target of providing 162,000

units across the city.

Rent controls

Implemented at the national level, rent controls provide a strong shield against unjust rent increases. In

the regulated rental market, allowable rent increases vary by the income of the tenant. In 2017, for

households with income below ¤40,349, the maximum increase was 2.8%, and for those above ¤40,349

it was 4.3% (van Brederode, 2018). How housing associations administer increases can vary, with some

increasing prices more for those who earn more and less for those who earn less. Housing associations

receive household income information from the central tax office, and they’re only allowed to use the

information for the purpose of calculating rent increases.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

30

Financing housing

Housing associations

Housing associations are the predominant providers of social housing in Amsterdam. At one time, they

owned more than half of all units in the city. Today, housing associations remain a significant housing

provider, responsible for 43.1% of units (184,300) in 2017, though this represents a decrease from 48.1%

(195,600) in 2011.

Nine housing associations operate in Amsterdam, and all are members of the AFWC. They are legally

required to provide “decent, available and affordable” housing for those meeting the stipulated income

requirements.

The role that housing associations play in providing housing in Amsterdam and the Netherlands has

changed over time. In the 1990s, they began to grow increasingly independent but were still charged

with the goal of improving the city’s provision of high-quality affordable housing, especially in light of

rent increases and shortages.

Housing associations cater to a broad range of tenants, but they do cap the rent in the majority of units

to ensure affordability. They often oversee a variety of units in order to cater to different income

groups, and as part of their role, they can invest in social infrastructure such as schools, doctors,

business incubators and other necessary facilities to create complete, safe and successful communities.

Point-based price setting

Both regulated rentals and housing associations use a point-based system to calculate rent for units

using quality indicators such as floor space, amenities and energy efficiency. Since 2015, property value

has been included as part of the point system. Due to rapid increases in property values in recent years,

this change has impacted the valuation system in an already pressurized market.

Subsidies

In the 1990s, the city made a shift from supply-side subsidies, which aim to support construction, to

demand-side subsidies such as rent allowances for tenants — a change supported by the strong housing

associations in Amsterdam. After 2008, Amsterdam limited such subsidies to households with incomes

of ¤35,000 or less and also provided subsidies to landlords that roughly equaled two months of rent per

year. These payments were determined based on income, rent prices and household size/type.

In 2017, the average housing cost in Amsterdam was 28.3% of income across all households. The

average cost was 27.3% of income for those receiving allowances and 28.8% for those not (Berkers &

Dignum, 2017).

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

31

References

https://www.afwc.nl/english

Berkers, V., & Dignum, K. (2017). Wonen in Amsterdam 2017 Woningmarkt. Gemeente Amsterdam

Federico Savini, Willem R. Boterman, Wouter P.C. van Gent and Stan Majoor. Amsterdam in the 21st

Century: Geography, Housing, Spatial Development and Politics, University of Amsterdam, Institute of

Geography, Planning and International Development Studies.

The Ineq-cities Project, “Amsterdam,” University College London,

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/ineqcities/atlas/cities/amsterdam

Jaco Boer, There Is Power in Unity, AFWC, March 2017,

http://www.afwc.nl/fileadmin/user_upload/Documenten/AFWC/Bestanden_2017/AFWC_100_jaar_EN

_march_2017.pdf

Jeroen van der Veer, Migration, Segregation, Diversification and Social Housing in Amsterdam, AFWC, June 19,

2017,

http://www.afwc.nl/fileadmin/user_upload/Documenten/AFWC/Bestanden_2017/5_Amsterdam_Jeroe

n_van_der_Veer.pdf

Maarten van Brederode, Affordable Rental Housing in Amsterdam and Berlin: A Comparison of Two European

Capital Cities, University of Amsterdam master’s thesis, June 11, 2018,

http://www.afwc.nl/fileadmin/user_upload/Bestanden_2018/THESIS_Maarten_van_Brederode_FINAL.P

DF

Melanie Hekwolter, Rob Nijskens and Willem Heeringa, The Housing Market in Major Dutch Cities, De

Nederlandsche Bank, 2017,

https://www.dnb.nl/en/binaries/The%20housing%20market%20in%20major%20Dutch%20cities_tcm47

-358879.pdf

Michael J. Wintle, “Amsterdam,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/place/Amsterdam

StatLine, “Population Dynamics; Birth, Death and Migration per Region,”

http://statline.cbs.nl/Statweb/publication/?DM=SLEN&PA=37259eng&D1=0-1,3,8-9,14,16,21-

22,24&D2=0&D3=93&D4=0,10,20,30,40,(l-1)-l&LA=EN&VW=C

World Cities Culture Forum, “Amsterdam,” 2020,

http://www.worldcitiescultureforum.com/cities/amsterdam/data

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

32

6. Tokyo

Key findings

1. Planning rules have been relaxed. The city has encouraged development by simplifying zoning

rules, increasing density allowances and giving all landowners near-total freedom to develop on

land that they own. This freedom is available not only to large developers but to anyone who owns

land and can secure the funding and financing required.

2. Decision-making is top-down. Planning decisions are made at the national level, enabling a more

strategic approach. However, sometimes the goals of the federal government and the desires of

the local government are at odds.

3. The government provides financing. A program offering government-backed low-interest, long-

term mortgages allows much of the population to purchase property with confidence and without

the risk of unaffordable interest rate increases.

4. There is a large-scale housing and infrastructure agency. A government-backed agency aims to

enable and stimulate urban development. This ensures that the national government has a stake in

new development and a vested interest in its success. In addition to assisting developers, the

agency can deliver longer-term, more strategic development projects.

5. Housing is a home, not a commodity. Housing is seen as a necessity and not a commodity that can

yield a profit. The relatively short life expectancy of Japanese housing reinforces this culture. For

example, it is common that a housing unit be purchased and at the end of its useable life to hold

nearly no value, it is not expected to be a means for the owner to accumulate wealth.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

33

Housing stock overview

The most common housing tenure in Tokyo is rented housing, with just over 2.4 million units being

privately rented. Between these private rentals and owner-occupied units, the total number of units

provided through the private sector is almost 5.4 million units. In Tokyo, government-owned housing

makes up a relatively small proportion of the housing stock.

Housing type (2013)

Number of

dwellings

Percent

of

category

Percent of total

housing market

Rentals

Owned by local government

268,200

9

4.1

Owned by Urban Renaissance or other

public corporations

232,200

7

3.6

Private rentals

2,432,200

75

37.6

City provided social housing

167,000

5

2.6

Total rentals

3,100,200

47.9

Owner-occupied

2,962,100

45.8

Other

410,300

6.3

Total dwellings

6,472,600

100

Source:

e-Stat, https://www.e-stat.go.jp/en/stat-

search/files?page=1&query=tokyo&layout=dataset&toukei=00200522&tstat=000001063455

47.9

45.8

6.3

Housing Type in 2013 (%)

Rentals Owner-occupied Other

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

34

Policy

In Tokyo, and in Japan as a whole, buildings (including housing) are rebuilt every 20 to 30 years, largely

to accommodate rapidly changing technological advances in earthquake resilience. This results in a

constant cycle of work for construction workers and a higher demand for new properties. At the end of

its 20- to 30-year life span, housing can be virtually valueless.

Due to the changing policy rules around land use planning and this constant recycling of housing and

buildings, there tends to be less opposition to housing in Japan as a whole.

Land use

The national government is responsible for most land use planning decisions, with a particular

preference for projects that boost economic development. Japan uses a relatively simple 12-category

zoning system for all land use planning across the country. Because land use planning happens at the

national level, some decisions may conflict with local government aspirations.

Urban density standards have been increased and housing regulations have been relaxed so that

housing can be built almost anywhere, with limited protections for older neighborhoods. Together,

these measures encourage high-density urban development to occur with relative ease. Most

developments are multifamily buildings of three or more stories in height. However, this rapid growth

and push to density has not resulted in the average unit being smaller.

According to estimates, 100,000 new units are started every year in Tokyo alone, which means that

supply matches, and at times surpasses, the total demand in the city. Though still very expensive, Tokyo

is often ranked as one of the most affordable megacities for housing.

Importantly, Japan focuses on supporting this urban development with a fast, efficient and extensive

transportation network centered on high-capacity public transit serving its urban populations.

Urban Renaissance Law

One of the biggest changes to occur in Japanese planning was the passage of the Urban Renaissance

Law (URL) in 2002. During the 1980s, like much of the more “westernized” world, Tokyo and Japan

were grappling with the issue of inflated housing markets, with bubbles that were at risk of collapse. The

government recognized that this issue was partly exacerbated by urban and land use planning

approaches.

To remedy the problem, the URL removed municipalities’ abilities to control private property and gave

land and building owners the right to build a broad range of uses on their land, at times in direct conflict

with what their neighbors or the local government wants.

SPUR Housing Research

International Examples of Housing Delivery

AECOM

35

Financing housing

Urban Renaissance Agency

The national Urban Renaissance Agency (URA) seeks to create a demographic mix in the developments