FEDERAL SUBSIDIES AND

THE HOUSING GSEs

The Congress of the United States

Congressional Budget Office

NOTES

Numbers in the text and tables may not add up to totals because of rounding.

All years referred to in this study are calendar years.

Preface

T

his study responds to a request from Congressman Richard H. Baker—in his capacity as

Chairman of the Subcommittee on Capital Markets, Insurance, and Government

Sponsored Enterprises, House Committee on Financial Services—that the Congressional

Budget Office (CBO) update its May 1996 study

Assessing the Public Costs and Benefits of

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

. That study provided an estimate of the value of the federal

subsidy to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. Congressman Baker also asked that CBO extend the

estimate to include the Federal Home Loan Banks and to update its estimate of the portion of

the subsidy that the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) retain.

Congressman John M. Spratt, Ranking Member, House Committee on the Budget,

separately requested an explanation of the methods and assumptions that CBO used in prepar-

ing its updated estimate. In addition, Senator Robert F. Bennett, Chairman, Subcommittee on

Financial Institutions, and Senator Wayne Allard, Chairman, Subcommittee on Housing and

Transportation, both of the Senate Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs, jointly

requested that CBO review two critiques of its previous work that were prepared under contract

for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. This study also responds to those requests.

Deborah Lucas and Marvin Phaup prepared this study, with the assistance of David

Torregrosa and Lauren Marks and under the direction of Steve Lieberman and Roger Hitchner.

Barry Anderson, Charles Capone, Arlene Holen, Angelo Mascaro, John McMurray, Eric

Warasta, and Rae Roy of CBO also contributed to the report. Many people outside CBO

provided assistance, including staff of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, Joe MacKenzie of the

Federal Housing Finance Board, Patrick Lawler and Robert Seiler Jr. of the Department of

Housing and Urban Development’s Office of Federal Housing Enterprise Oversight, Edward

DeMarco and Mario Ugoletti of the Department of the Treasury, Wayne Passmore of the

Federal Reserve Board, Ron Feldman of the Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis, Bill Shear

of the General Accounting Office, and Barbara Miles of the Congressional Research Service.

Under contract with CBO, Brent Ambrose and Arthur Warga prepared a report in support

of this study:

An Update on Measuring GSE Funding Advantages,

which is available from

CBO’s Microeconomic and Financial Studies Division. Also, David Torregrosa authored the

supporting CBO paper

Interest Rate Differentials Between Jumbo and Conforming Mortgages,

1995-2000.

John Skeen edited this study, and Christine Bogusz proofread it. Kathryn Quattrone

prepared it for publication, Annette Kalicki prepared the electronic versions for CBO’s Web

site, and Lenny Skutnik did the initial printing. Kathryn Quattrone, with the assistance of Binh

Thai, designed the cover. This study and other CBO publications are available at CBO’s Web

site (www.cbo.gov).

Dan L. Crippen

Director

May 2001

Contents

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY 1

The Housing GSEs 1

Risk, Return, and Financial Structure 3

CBO’s Estimation Procedure 4

THE HOUSING GSEs’ STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION 7

The Housing GSEs’ Borrowing, Investing,

and Lending 7

Fannie Mae’s and Freddie Mac’s Guarantees

of Mortgage-Backed Securities 9

The Regulatory Environment 10

FEDERAL SUBSIDIES 13

Direct Benefits from Special Legal Status 13

Indirect Benefits That Lower Borrowing Costs 14

The Subsidy to Mortgage-Backed Securities 14

ESTIMATING THE SUBSIDIES 15

The Direct Benefits of Regulatory and Tax Exemptions 15

The Subsidy to General Obligation Debt Securities 15

The Subsidy to Mortgage-Backed Securities 22

Putting the Elements Together: The Total Subsidy 23

ESTIMATED DISTRIBUTION OF BENEFITS 25

SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS 29

APPENDIXES

A Responses to Analyses of the Congressional

Budget Office’s 1996 Subsidy Estimates 33

B Subsidy Estimates When Growth Is Permanent 37

vi FEDERAL SUBSIDIES AND THE HOUSING GSEs May 2001

TABLES

1. Federal Subsidies to the Housing GSEs, 1995-2000 2

2. Balance Sheets for Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and

the Federal Home Loan Banks, December 31, 2000 8

3. The Housing GSEs’ Outstanding Mortgage-Backed

Securities and Debt, Year-End 1985-2000 10

4. Annual Value of Tax and Regulatory Exemptions for

the Housing GSEs, 1995-2000 16

5. Subsidies to GSE Debt, 1995-2000 21

6. Subsidies to Mortgage-Backed Securities Guaranteed

by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, 1995-2000 22

7. Total Federal Subsidies to the Housing GSEs, 1995-2000 23

8. Distribution of Subsidies by Intermediary and

Beneficiary, 1995-2000 28

9. Sensitivity Analysis of CBO’s Base Case of Federal

Subsidies to the Housing GSEs 30

A-1. Fannie Mae’s and Freddie Mac’s Estimated Share of

One- to Four-Family Mortgages, December 31, 2000 34

B-1. Federal Subsidies to the Housing GSEs Using a Perpetual

Horizon, 1995-2000 37

FIGURES

1. Fannie Mae’s and Freddie Mac’s Ratio of Outstanding

Debt to Mortgage-Backed Securities, 1986-2000 3

2. Growth in the Housing GSEs’ Outstanding

Debt and Mortgage-Backed Securities, 1995-2000 4

3. Total Subsidies to the Housing GSEs Under

Three Scenarios, 1988-2011 24

4. Distribution of Subsidies by Beneficiary, 1996-2000 26

Introduction and Summary

F

annie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Home

Loan Bank (FHLB) System were established

and chartered by the federal government, as

privately owned entities, primarily to facilitate the

flow of credit to mortgage borrowers. Their special

legal status as government-sponsored enterprises

(GSEs), which includes tax and regulatory exemp-

tions, enhances the perceived quality of the debt and

mortgage-backed securities (MBSs) that they issue or

guarantee and translates into a federal subsidy. By

the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO’s) esti-

mates, the total subsidy grew steadily from $6.8 bil-

lion in 1995 to approximately $15.6 billion in 1999;

it dropped slightly, to $13.6 billion, in 2000, reflect-

ing a slowdown in the growth of the GSEs’ activities

(see Table 1). Although the single largest source of

the subsidy is the implicit guarantee on the GSEs’

debt issues, in recent years the value of tax and regu-

latory exemptions has become significant, totaling an

estimated $1.2 billion in 2000.

The ultimate beneficiaries of that subsidy in-

clude conforming mortgage borrowers; the share-

holders of (and other stakeholders in) Fannie Mae

and Freddie Mac; and the stakeholders in the FHLBs

and member institutions, including other borrowers at

member banks.

1

A little more than half ($7.0 billion)

of that total subsidy in 2000 passed through to con-

forming mortgage borrowers, CBO estimates.

The Housing GSEs

Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Home

Loan Banks—collectively, the housing GSEs—were

created to provide liquidity and stability in the home

mortgage market, thereby increasing the flow of

funds available to mortgage borrowers.

2

The oldest

of these enterprises, the FHLBs, were chartered in

1932 to provide short-term loans (called advances) to

thrift institutions to stabilize mortgage lending in lo-

cal credit markets. Fannie Mae was originally cre-

ated as a wholly owned government corporation in

1938 to buy mortgages, primarily from mortgage

bankers, and hold them in its portfolio. Although it

was converted into a GSE in 1968, Fannie Mae con-

tinued the practice of issuing debt and buying and

holding mortgages. Freddie Mac, created in 1970 as

part of the Federal Home Loan Bank System, bought

1. For Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, conforming mortgage borrowers

and shareholders are the primary beneficiaries of the subsidy. A

portion of the subsidy also accrues to other “stakeholders,” which

include any other party that benefits from those GSEs’ special sta-

tus. CBO has estimated the total subsidy and the subsidy accruing

to mortgage borrowers and therefore has not distinguished between

shareholders and other stakeholders. FHLB stakeholders are de-

fined as all beneficiaries of the subsidy that are not conforming

mortgage borrowers.

2. In general, GSEs are financial institutions established and chartered

by the federal government, as privately owned entities, to facilitate

the flow of funds to selected credit markets, such as residential

mortgages and agriculture. In addition to Fannie Mae, Freddie

Mac, and the Federal Home Loan Banks, the Farm Credit System

and Farmer Mac are GSEs. The Student Loan Marketing Associa-

tion (Sallie Mae) is in the process of converting from being a GSE

to being a fully private entity.

2 FEDERAL SUBSIDIES AND THE HOUSING GSEs May 2001

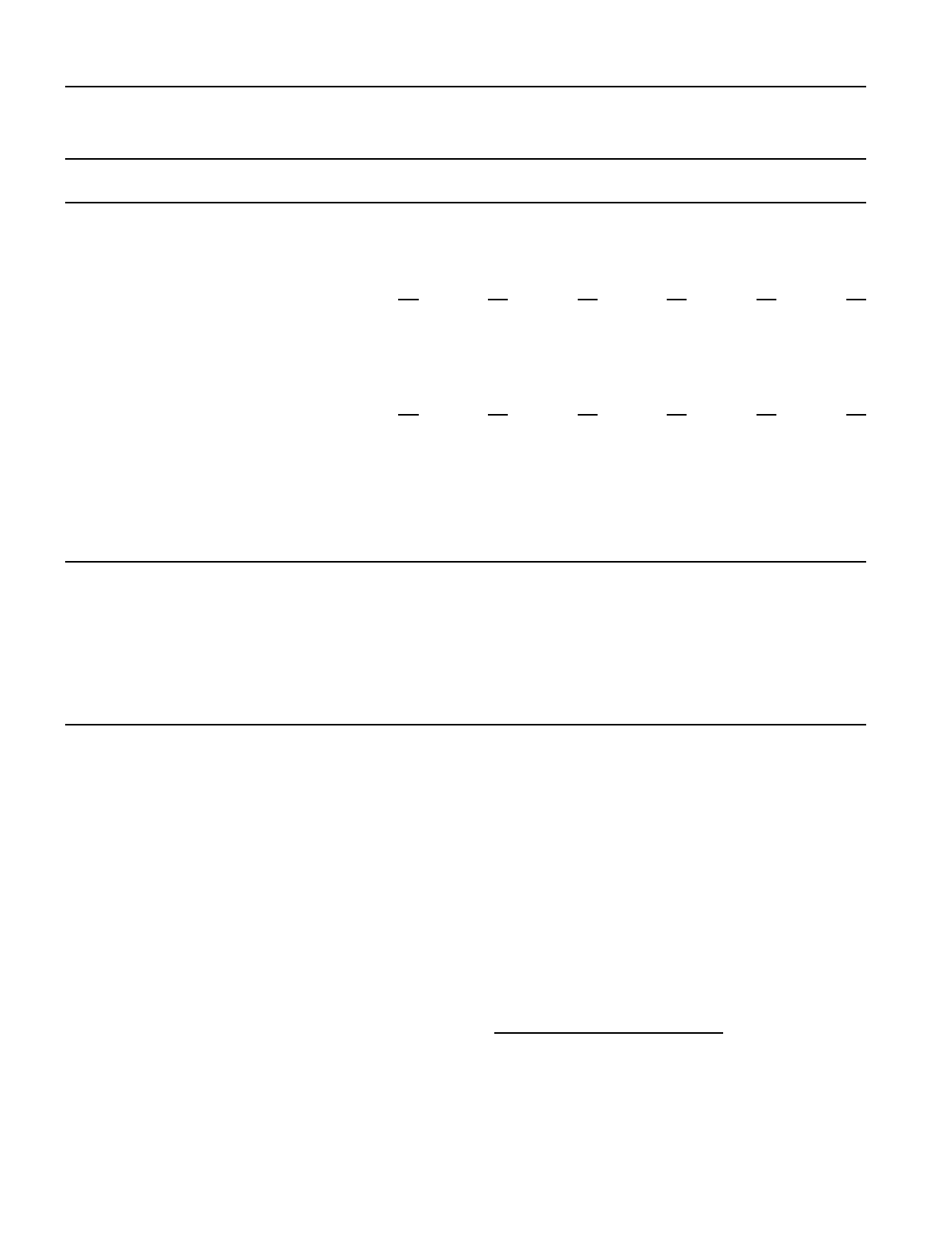

Table 1.

Federal Subsidies to the Housing GSEs, 1995-2000 (In billions of dollars)

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000

Subsidies by GSE and by Source

Fannie Mae

Debt 1.7 1.5 1.8 3.2 3.3 3.6

Mortgage-backed securities 1.5 1.7 1.7 2.3 2.1 1.9

Tax and regulatory exemptions 0.3 0.4 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.6

Freddie Mac

Debt 0.8 1.1 0.8 3.3 2.4 2.4

Mortgage-backed securities 1.0 1.3 1.1 1.1 2.1 1.8

Tax and regulatory exemptions 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.4

FHLBs

Debt 1.2 1.1 2.0 2.6 4.5 2.8

Tax and regulatory exemptions 0.2

0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2

Total 6.8 7.4 8.1 13.5 15.6 13.6

Subsidies by Recipient

Conforming mortgage borrowers

a

3.7 4.1 4.0 7.0 7.4 7.0

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac 1.8 2.2 2.1 3.9 3.9 3.9

FHLB stakeholders

b

1.3 1.1 2.0 2.6 4.3 2.7

Total 6.8 7.4 8.1 13.5 15.6 13.6

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office.

NOTE: The subsidies to GSE debt and mortgage-backed securities are present values. The annual savings from tax and regulatory exemp-

tions are for the current year only.

a. Conforming mortgages are loans that are eligible for purchase by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac with an original principal amount no greater

than a stated ceiling, which is currently $275,000 for single-family mortgages.

b. The estimates assume that conforming mortgages financed by FHLB members were a constant share of members’ portfolios from 1995 to

2000.

mortgages primarily from thrifts. Rather than hold-

ing the mortgages in its portfolio, Freddie Mac

pooled them, guaranteed the credit risk, and sold in-

terests in the pools to investors—creating mortgage-

backed securities.

The debt issued and MBSs guaranteed by the

housing GSEs are more valuable to investors than

similar private securities because of the perception of

a government guarantee and because of other advan-

tages conferred by statute. That added value is the

primary means by which the federal government con-

veys a subsidy to those GSEs.

3

Because of competi-

tive forces, a large part of the subsidy passes through

them and other financial intermediaries to the in-

tended beneficiaries—primarily mortgage borrowers,

3. Alan Greenspan has noted that “The GSE subsidy is unusual in that

its size is determined by market perceptions, not by legislation.

Indeed the prospectuses of the debentures issued by GSEs explicitly

state that they are not backed by the full faith and credit of the

United States government. Accordingly, the extent to which the

subsidy is exploited is determined by the extent to which GSEs

choose to issue debt and mortgage-backed securities, not by legisla-

tion.” Letter to Congressman Richard H. Baker, August 25, 2000.

May 2001 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY 3

1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

1.2

Ratio of Debt to MBSs

Fannie Mae

Freddie Mac

but also other borrowers of FHLB member institu-

tions. However, the shareholders and stakeholders of

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are able to retain a por-

tion of that subsidy because the special legal status of

those GSEs puts them at a competitive advantage

over other financial institutions in the market for

fixed-rate conforming mortgages. Similarly, to the

extent that competition is not perfect, stakeholders in

the FHLBs and member institutions retain a portion

of the subsidy to the banks.

Risk, Return, and

Financial Structure

The economic turmoil of the late 1970s and early

1980s demonstrated that the risks of financing a

mortgage portfolio can differ significantly from those

of guaranteeing MBSs or providing short-term loans.

High inflation, interest rate volatility, and recession

weakened Fannie Mae and the savings and loans.

Those conditions eroded the value of 30-year con-

forming mortgages held in portfolio and simulta-

neously drove up the cost of financing. Freddie Mac

and the FHLBs were much less exposed to the risk of

declines in the value of mortgages and, hence, were

less adversely affected than Fannie Mae.

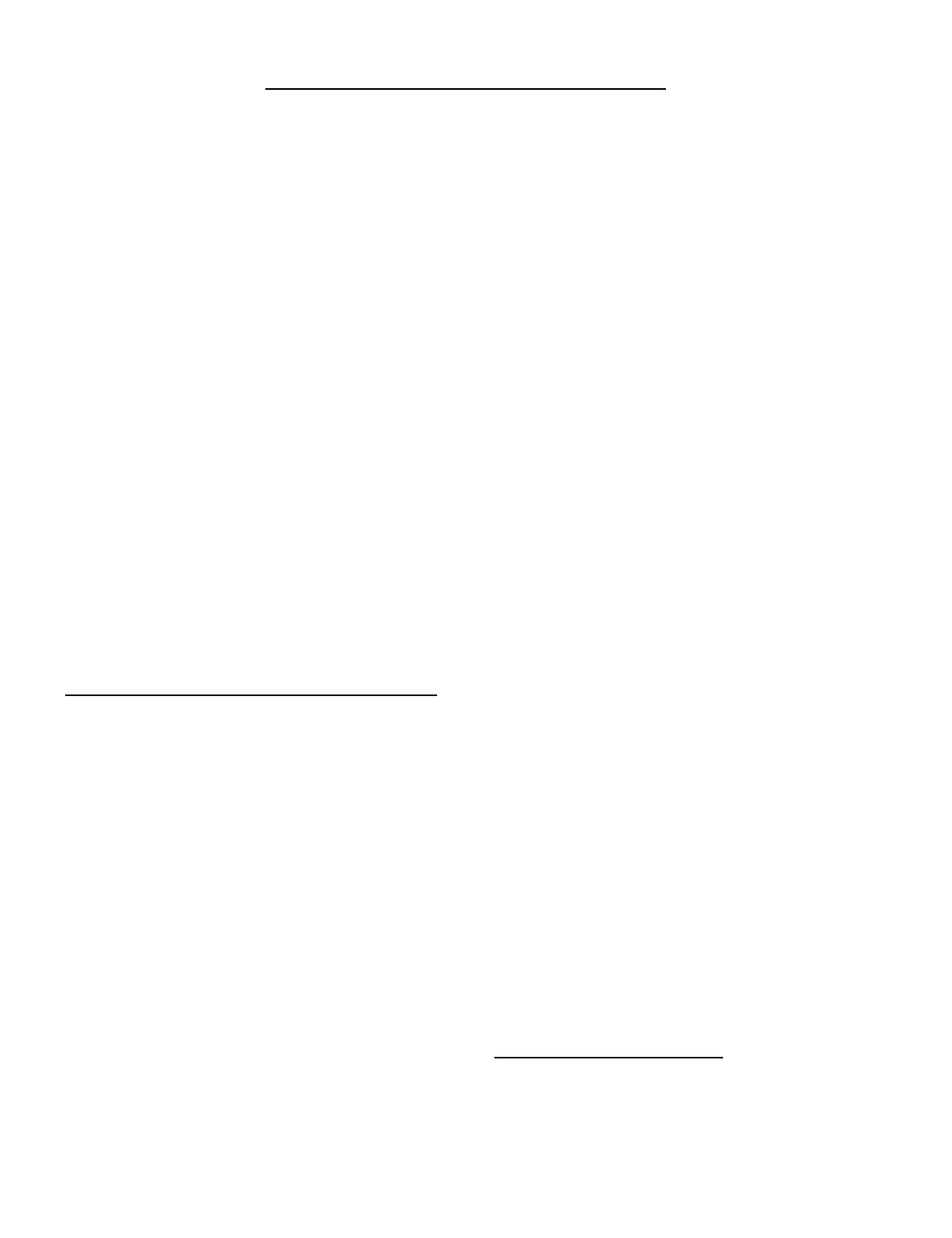

Beginning in 1982 and continuing for the next

decade, Fannie Mae rapidly increased its reliance on

MBSs, reducing the growth of its exposure to the

types of risks that threatened its solvency in the early

1980s. Then in the early 1990s, Fannie Mae changed

its practices and again began to buy and hold mort-

gages (financed by debt issues) in addition to guar-

anteeing MBSs, and Freddie Mac subsequently fol-

lowed. Consequently, for both GSEs, the ratio of

mortgages held in portfolio to MBSs guaranteed but

held by other investors greatly increased (see Figure

1). To support their mortgage portfolios, Fannie Mae

and Freddie Mac currently have $1.1 trillion of out-

standing debt at interest rates below those on compa-

rable private debt. Although the increased reliance

on portfolio holdings represents an increase in risk

taking, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac now hedge

many of those risks. Nonetheless, their portfolios

have become a large and growing source of profits

for both enterprises.

Figure 1.

Fannie Mae’s and Freddie Mac’s Ratio

of Outstanding Debt to Mortgage-Backed

Securities, 1986-2000

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office.

NOTE: MBSs = mortgage-backed securities.

The portfolios of Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

may augment their government-legislated mission to

provide liquidity, although at the cost of greater risk

exposure than if they only guaranteed MBSs. By

buying and holding mortgages, especially those origi-

nated in distressed areas such as Texas in the late

1980s and New England in the mid-1990s, they di-

rectly enhanced liquidity in those markets. More

generally, the profits from their portfolios provide

funding for improving mortgage financing for con-

sumers. However, whether the costs of that growth

in their portfolios are commensurate with the addi-

tional contributions to the home mortgage market is

unclear. If the housing GSEs were to continue to

grow at the rate of gross domestic product (GDP),

their total subsidy would exceed $20 billion in 2011.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have demonstrated the

feasibility of increasing the liquidity and stability in

local housing markets by integrating them into a sin-

gle national system. In the process, they have at-

tracted private imitators, firms that pool mortgages

and sell MBSs without the benefit of federal backing.

The FHLBs also borrow at rates below those on

comparable private securities because of the market

perception of a government guarantee on their debt.

Originally, the FHLBs made advances directly to

4 FEDERAL SUBSIDIES AND THE HOUSING GSEs May 2001

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000

0.00

0.05

0.10

0.15

0.20

0.25

0.30

0.35

Annual Percentage Growth

Debt

Total

MBSs

members, which were mostly savings institutions that

specialized in mortgage lending. In so doing, the

FHLBs passed through most of the subsidy to their

members, who in turn distributed the subsidy primar-

ily to home buyers. The regulatory reform that fol-

lowed the savings and loan crisis broadened member-

ship in the FHLB System to include banks and thrifts

that operate the way banks do. Consequently, the

FHLBs’ subsidy is now spread more widely among

lending institutions and is not confined to housing

finance.

CBO’s Estimation Procedure

The total subsidy to the GSEs on their debt is esti-

mated using three steps. First, the yield advantage on

GSE debt is estimated by comparing GSEs’ yields

with the higher yields on comparable issues from

other financial institutions.

4

Second, that difference

is multiplied by the amount of new debt issued in the

current year. That yield advantage is also multiplied

by the amount of new debt estimated to remain out-

standing in future years. Those future annual reduc-

tions in borrowing cost represent subsidies secured in

the current year but expected to be realized in the

future. Finally, current and future annual subsidies

are capitalized at a discount rate equal to the GSEs’

borrowing cost, producing the current year’s total

subsidy.

5

This calculation produces a total subsidy to

debt issued in 2000 of $8.8 billion. An analogous

procedure yields a total subsidy to MBSs of $3.7 bil-

lion in 2000.

This capitalized subsidy measure recognizes

benefits when securities are issued and mortgages are

purchased or securitized. That measure of the incre-

mental benefit of new securities issued and mort-

gages financed is consistent with the objectives of

Figure 2.

Growth in the Housing GSEs’ Outstanding

Debt and Mortgage-Backed Securities, 1995-2000

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office.

NOTE: MBSs = mortgage-backed securities.

generally accepted federal accounting principles and

budgetary practices but represents a methodological

change from previous estimates, including CBO’s

last estimate of the subsidy to the GSEs. The princi-

pal advantage of the current approach is that it ties

the measure of the subsidy to the GSEs’ new activi-

ties, not old commitments. For example, the current

measure of the subsidy rose sharply in 1998 and

1999, which were years of rapid growth in the vol-

ume of securities issued by Fannie Mae, Freddie

Mac, and the FHLBs, but declined in 2000, when the

rate of growth fell back to the pre-1998 pace (see Fig-

ure 2).

CBO has also estimated the division of the sub-

sidy among the major beneficiaries, including the

portion of the subsidy that reaches conforming mort-

gage borrowers in the form of lower interest rates.

On the basis of the estimated differential between

rates for jumbo fixed-rate single-family mortgages

(ones that are above $275,000 in 2001) and conform-

ing mortgages (ones that are $275,000 and below in

2001 and are eligible for purchase by Fannie Mae

and Freddie Mac) and an adjustment for the FHLBs’

influence on the rates for jumbo mortgages, CBO

estimates that interest rates on mortgages are reduced

by one-quarter of one percentage point (0.25 percent-

age points, or 25 basis points) as a result of the fed-

eral subsidy. A small portion of that subsidy (3 basis

4. The comparison is based on debt issues by 70 of the largest

banking-sector firms rated either A or AA during the period of 1995

to 1999 and issues by the GSEs over the same period. For details,

see Brent Ambrose and Arthur Warga,

An Update on Measuring

GSE Funding Advantages

(prepared for the Congressional Budget

Office, November 6, 2000), Table 1.

5. CBO’s 1996 estimate applied the yield advantage to the total out-

standing debt, rather than to incremental debt, but only for a single

year. Therefore, the subsidy estimates here are not directly compa-

rable with those from the earlier study.

May 2001 INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY 5

points) is provided on jumbo mortgages via the

FHLBs, which pass it through to their members, who

in turn pass it through to their customers. The sub-

sidy on jumbo mortgages is relatively small because

it is spread across the total business of FHLB mem-

bers and jumbo mortgages make up a small portion of

that business.

The estimated savings to conforming mortgage

borrowers are also expressed as a capitalized amount,

reflecting the fact that the benefit from lower mort-

gage rates lasts over the life of the mortgage. About

$7.0 billion of the total subsidy of $13.6 billion was

passed through to conforming mortgage borrowers by

the housing GSEs in 2000. Of that $7.0 billion, the

subsidy to borrowers from mortgages financed by

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac was $6.7 billion. Be-

cause conforming mortgages are Fannie Mae’s and

Freddie Mac’s only major line of business, CBO as-

sumes that the portion of the subsidy not passed

through is retained by shareholders and other stake-

holders. Subtracting the amount of subsidy passed

through by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac from their

total subsidy ($10.6 billion minus $6.7 billion in

2000) leaves $3.9 billion (or about 37 percent) as the

amount that they retained.

Determining the disposition of the subsidy to

the FHLBs is more complicated because their mem-

ber banks engage in a variety of lending and other

activities. CBO estimates that their conforming mort-

gage borrowers receive $0.3 billion out of the $3.0

billion total subsidy, assuming that the reduction in

rates passed through is the same as for loans pur-

chased by Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac and recogniz-

ing that about 15 percent of member banks’ assets are

conforming mortgages. CBO assumes that the bal-

ance reduces borrowing rates on other types of loans

and accrues to other FHLB stakeholders.

As for all such calculations, data limitations and

the complexity of the issues about which judgments

must be made suggest that there is significant uncer-

tainty surrounding those point estimates. The sensi-

tivity analysis described in the last section of this

study shows that changing some of the key parame-

ters could significantly raise or lower the subsidy

estimates. An important question is whether the ap-

proximation errors in the sensitivity analysis are off-

setting. Certain assumptions that CBO has made may

result in a downward bias: analyzing short-lived

rather than long-lived subsidies; relying on an aver-

age funding advantage over time rather than acknowl-

edging that the GSEs adjust the amount of debt they

issue according to the size of the funding advantage;

and not attributing an advantage to the GSEs in the

derivatives markets. Other assumptions, such as bas-

ing the yield advantage largely on a sample of firms

that have a lower credit rating than Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac and attributing no borrowing advantage

to the efficiency of the GSEs’ operations, may result

in an upward bias. CBO believes that on balance its

estimates present a fair picture of the total subsidy,

its distribution, and its growth over time.

In preparing its estimates, CBO considered the

comments of Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and their

consultants on CBO’s 1996 study. Some of their sug-

gestions were incorporated into the present analysis,

but disagreements remain on several fundamental

issues. Appendix A summarizes the main points

raised and CBO’s responses.

The Housing GSEs’ Structure

and Function

G

overnment-sponsored enterprises are financial

intermediaries, established and granted pref-

erential treatment by federal law to increase

the flow of funds to specific uses but owned by in-

vestors to whom they owe a fiduciary responsibility.

1

Three GSEs facilitate the financing of residential

housing: the Federal National Mortgage Corporation,

or Fannie Mae; the Federal Home Loan Mortgage

Corporation, or Freddie Mac; and the Federal Home

Loan Bank (FHLB) System. Fannie Mae and Freddie

Mac are publicly owned entities whose shares trade

on the New York Stock Exchange. The 12 Federal

Home Loan Banks are cooperatives, which operate

somewhat independently of one another, and are

owned by member institutions, primarily privately

owned savings and loans, savings banks, commercial

banks, and other lenders that finance home mortgages

and other household and business debt.

All of the housing GSEs are financial intermedi-

aries. They raise funds in the capital markets and

make the money available to retail lenders, who in

turn provide financing for their customers. Fannie

Mae and Freddie Mac are largely restricted to financ-

ing conforming mortgages, which are high-quality

loans secured by residential real estate whose original

principal amount is no greater than the conforming

ceiling, currently $275,000 for single-family mort-

gages.

2

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac supply funds to

the conforming mortgage market in two ways: they

borrow money by selling debt securities and use the

funds to purchase mortgages from lenders. In addi-

tion to buying mortgages and holding them as invest-

ments, Fannie and Freddie also guarantee mortgage-

backed securities, which are then sold to investors.

The principal business activity of the FHLBs is to

borrow in the capital markets and make loans (called

advances) to member institutions. All three activities

affect the supply of funds available for mortgage

lending and are likely to reduce interest rates on

loans secured by residential real estate, but each does

so through different financial channels.

The Housing GSEs’

Borrowing, Investing,

and Lending

As their balance sheets show, Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac are heavily invested in mortgages and

depend on debt securities for funding. The FHLBs

have two-thirds of their assets invested in advances to

member banks and similarly depend on debt securi-

ties for funding (see Table 2). The GSEs’ second

1. For a discussion of the evolution of GSEs, see the Statement of

Thomas Woodward, Congressional Research Service, before the

Subcommittee on Capital Markets, Securities, and Government-

Sponsored Enterprises, House Committee on Banking and Financial

Services, and the Subcommittee on Government Management, In-

formation, and Technology, House Committee on Government Re-

form and Oversight, July 16, 1997.

2. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac adjust the conforming ceiling annu-

ally for the change in house prices. In 2000, the ceiling was

$252,700.

8 FEDERAL SUBSIDIES AND THE HOUSING GSEs May 2001

Table 2.

Balance Sheets for Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Home Loan Banks, December 31, 2000

(As a percentage of total assets)

Fannie Mae Freddie Mac FHLBs

Assets

Mortgage portfolio 90 84 2

Investments 8 11 29

Advances n.a. n.a. 67

Other assets 2

5 2

Total Assets 100 100 100

Liabilities and Capital

Debt securities 95 93 91

Other borrowing 2 4 4

Equity 3

3 5

Total Liabilities and Capital 100 100 100

Total Assets (In billions of dollars) 675 459 654

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office.

NOTES: As of December 31, 2000, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac had contingent liabilities for outstanding mortgage-backed securities of $707

billion and $576 billion, respectively.

n.a. = not applicable.

largest category of assets, investments, includes com-

mercial paper (a type of short-term corporate debt);

overnight bank loans; and, for the FHLBs, holdings

of mortgage-backed securities. (Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac report their investments in MBSs as a

part of their mortgage portfolios.)

3

The GSEs profit from simultaneously borrowing

and lending, because the income they earn from as-

sets is higher than the interest they must pay on debt

plus their other operating costs. In 1999, Fannie Mae

reported an average annual yield on its mortgage

portfolio of 0.90 percentage points, or 90 basis points

(bps), greater than the cost of its outstanding debt.

4

Freddie Mac reported a yield spread on mortgages

over debt of 80 bps. And the FHLBs, which special-

ize in making low-interest loans to members, reported

a spread on earning assets over debt securities of 22

bps. Thus, by selling general obligation debt to in-

vestors, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are able to

profitably hold large portfolios of mortgages that they

purchase from lenders.

5

The FHLBs earn a smaller,

but positive, yield based on the spread between the

higher rates on loans to members and the lower rates

that the banks pay on their debt.

Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the FHLBs issue

debt securities in both noncallable and callable forms

and with various maturities. In addition, the GSEs

use derivative instruments such as interest rate swaps

to alter the effective maturity of their debt. Noncall-

able, or “bullet,” issues pay interest semiannually, but

the principal is redeemed only at the stated maturity

of the debt. Callable debt securities differ from non-

callable debt in that the principal may be repaid at a

GSE’s option on or after a specified call date and

3. Fannie Mae’s and Freddie Mac’s contingent liabilities for guaran-

tees of outstanding MBSs are classified as “off-balance-sheet” and

disclosed elsewhere in their financial statements.

4. According to Fannie Mae’s 1999 annual report, the average yield

on its net mortgage portfolio was 7.08 percent, and the average cost

of outstanding debt was 6.18 percent.

5. The annual return on equity from 1995 to 2000 averaged 24.3 per-

cent for Fannie Mae and 23.5 percent for Freddie Mac.

May 2001 THE HOUSING GSEs’ STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION 9

before the maturity date. The GSEs offer debt across

the full range of maturities, from a few days to 30

years and with both fixed and variable interest rates.

The wide range of debt securities that the GSEs issue

is intended to appeal to a variety of investors and to

minimize funding costs to the enterprises. The need

to manage risk also affects the maturity composition

of the debt.

6

Fannie Mae’s and

Freddie Mac’s Guarantees

of Mortgage-Backed Securities

Mortgage-backed securities are created when a finan-

cial institution purchases individual mortgages but

then, rather than holding them on its balance sheet as

assets, bundles them into a pool of mortgages and

sells shares of the mortgage pool to investors. The

claims sold to investors are mortgage-backed securi-

ties. MBSs differ from traditional debt instruments

that promise a series of predetermined payments to

investors. Instead, MBSs pay a share of the often

uneven and somewhat unpredictable cash flows from

the underlying pool of mortgages. A third party’s

credit guarantee of an MBS provides assurance to the

investor of receiving payments when due, but actual

cash flows depend on the speed of underlying mort-

gage prepayments. If, for example, mortgage interest

rates fall sharply, mortgage borrowers are more likely

to prepay their mortgages, as a result of either selling

or refinancing their homes, than if rates had stayed

unchanged or risen. Investors in the MBSs will then

receive their payments of principal more quickly than

they may have expected. Thus, investors in MBSs,

like investors in insured whole mortgages, are subject

to a risk that investors in traditional debt instruments

avoid: the risk associated with the uncertainty of the

speed of repayment, or prepayment risk. Partly as a

consequence of that risk, interest rates on MBSs (and

whole mortgages) are higher than on debt securities

of comparable credit quality.

7

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are actively in-

volved in the production of MBSs. (The Federal

Home Loan Banks issue only debt securities.) While

the operating details differ sufficiently to cause Fan-

nie Mae and Freddie Mac to describe their activities

variously as “credit guarantees” (Fannie Mae) and

“mortgage securitization” (Freddie Mac), both enti-

ties effectively provide a guarantee of timely pay-

ment on MBSs. In both cases, the GSE assumes the

credit or default risks (for a fee), and the investor ac-

cepts the prepayment risk (in exchange for a higher

rate of return than on a noncallable debt security).

Because Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are not re-

quired to report on their balance sheets the MBSs that

they guarantee but do not hold in portfolio, important

elements of risk and return are missing from those

balance sheets.

8

A more complete picture would in-

clude the substantial volume of liabilities for out-

standing guarantees of MBSs. Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac had more than $1.2 trillion in MBSs

outstanding at year-end 2000 (see Table 3). Those

guarantees are important sources of risk and of fee

income for the two enterprises.

In recent years, the housing GSEs have also be-

come major investors in MBSs guaranteed by them-

selves and others. By purchasing MBSs, the GSEs

increase their risk and potential returns. When Fan-

nie Mae and Freddie Mac purchase MBSs they have

already guaranteed, they transform off-balance-sheet

liabilities into on-balance-sheet assets and on-

balance-sheet liabilities for debt securities issued to

finance the purchase. In doing so, they take on the

prepayment, interest rate, and liquidity risks in addi-

tion to the credit risk they had already assumed.

When they invest in MBSs guaranteed by others, they

are taking on prepayment, interest rate, and liquidity

risks but little incremental credit risk.

6. Like other financial institutions, the GSEs are exposed to interest

rate risk when the effective duration of their assets and liabilities

does not match. The enterprises select debt maturities in part to

offset that risk.

7. Like other investors in debt, investors in MBSs also face interest

rate and liquidity risks. Interest rate risk is due to the effect of

changing market rates on the value of debt securities. Liquidity risk

is the risk that an active secondary market will not be available

when an investor wants to sell a security quickly.

8. However, the enterprises do disclose their guarantees of MBSs in

various financial statements.

10 FEDERAL SUBSIDIES AND THE HOUSING GSEs May 2001

Table 3.

The Housing GSEs’ Outstanding Mortgage-Backed Securities and Debt, Year-End 1985-2000

(In billions of dollars)

Fannie Mae Freddie Mac FHLBs’ Total Total

MBSs

a

Debt MBSs

a

Debt Debt MBSs

a

Debt

1985 55 94 100 13 74 155 181

1986 96 94 169 15 90 265 199

1987 136 97 213 20 116 349 233

1988 170 105 226 27 137 396 269

1989 217 116 273 26 137 490 279

1990 288 123 316 31 118 604 272

1991 355 134 359 30 108 714 272

1992 424 166 408 30 115 832 311

1993 471 201 439 50 139 910 390

1994 486 257 461 93 200 947 550

1995 513 299 459 120 231 972 650

1996 548 331 473 157 251 1,021 739

1997 579 370 476 173 304 1,055 847

1998 637 460 478 287 377 1,115 1,124

1999 679 548 538 361 525 1,217 1,434

2000 707 643 576 427 592 1,283 1,662

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office based on data from the Department of Housing and Urban Development’s Office of Federal Housing

Enterprise Oversight.

a. MBSs = mortgage-backed securities; excludes holdings of the enterprise’s own MBSs held in its portfolio.

The Regulatory Environment

In common with commercial banks and savings insti-

tutions, the GSEs are subject to regulations that af-

fect their business operations, capital holdings, and

participation in lending to low-income borrowers, as

well as other activities. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac

are regulated by the Department of Housing and Ur-

ban Development’s (HUD’s) Office of Federal Hous-

ing Enterprise Oversight (OFHEO), and the Federal

Housing Finance Board oversees the Federal Home

Loan Banks.

In accord with their housing mission, Fannie

Mae and Freddie Mac are limited primarily to financ-

ing conforming mortgages. That limitation, however,

excludes them from only about 10 percent to 20 per-

cent of the residential mortgage market. Lending by

the FHLBs is largely restricted to collateralized loans

to member institutions. Eligible collateral includes

home mortgages, mortgage-backed securities, Trea-

sury and agency securities, and deposits with the

FHLBs.

9

Those collateral requirements are intended

to ensure that most lending by the FHLBs supports

targeted investment activities, but because member

institutions have more eligible collateral than ad-

vances from the FHLBs, the requirements are thought

to not be effective in targeting the use of those

funds.

10

The housing GSEs are subject to minimum capi-

tal requirements. OFHEO sets the capital standards

for Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and the Federal

9. For commercial member banks with less than $500 million in as-

sets, the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act of 1999 repealed a requirement

that 10 percent of their total assets be mortgage-related and revised

the definition of eligible collateral to include small business and

small farm loans. For the details and projected effects, see Robert

N. Collender and Julie A. Dolan, “Small Commercial Banks and the

Federal Home Loan Bank System” (paper presented at the North

American Regional Science Association International Meeting,

Chicago, Ill., November 2000).

10. At year-end 1999, FHLB member institutions held $1.1 trillion in

residential mortgages, while advances were $400 billion. There-

fore, members were able to borrow against existing excess collateral

and use the funds to finance the most attractive lending opportuni-

ties, which may or may not have been mortgages.

May 2001 THE HOUSING GSEs’ STRUCTURE AND FUNCTION 11

Housing Finance Board has responsibility for ensur-

ing that the Federal Home Loan Banks maintain the

mandated level of equity capital.

11

The housing GSEs are charged with increasing

the availability of mortgages for low- and moderate-

income borrowers. HUD establishes goals for fi-

nancing such mortgages for Fannie Mae and Freddie

Mac, and the FHLBs are required by law to devote 10

percent of net income to the Affordable Housing Pro-

gram, which offers subsidized mortgages to targeted

borrowers. Any additional benefits to low-income

borrowers (beyond the estimated rate reduction on

their conforming mortgages) are not estimated here.

11. Mandated capital levels are lower for the GSEs than for commercial

banks, but interpreting those differences is difficult because the

risks borne by those two types of institutions also differ signifi-

cantly.

Federal Subsidies

T

he housing GSEs receive two distinct, but re-

lated, benefits from the government. First, a

number of regulatory and tax exemptions re-

duce the GSEs’ operating costs. Second, federal

backing enhances the perceived credit quality of debt

issued and mortgage-backed securities guaranteed by

the GSEs. Those benefits result in lower borrowing

costs and higher profits than a similarly structured

enterprise without a GSE charter would realize.

CBO has estimated the costs of those subsidies

in two parts: First, there is the direct cost from the

fees and taxes that otherwise would be collected by

federal, state, and local governments. Second, there

is the opportunity cost of providing free credit en-

hancement to the GSEs, because competing financial

institutions would be willing to pay to receive similar

treatment. To the extent that the government as-

sumes credit risk, there is also the cost of expected

losses, but quantifying that potential exposure is be-

yond the scope of this estimate.

1

As requested by Congressman Baker, CBO’s

estimate breaks down the distribution of those subsi-

dies among various beneficiaries. They include the

GSEs’ stakeholders, conforming mortgage borrowers

who are financed via the GSEs, and other entities (for

example, nonmortgage borrowers at FHLB member

banks). The GSEs may indirectly affect borrowing

rates for other financial market participants as well.

For instance, rates on conforming mortgages obtained

from intermediaries that are not GSEs are lower than

they otherwise would be because of the competitive

presence of the GSEs, benefiting those borrowers. At

the same time, credit that is diverted from other mar-

kets to the conforming mortgage market tends to raise

costs to borrowers in those markets—for instance, for

the U.S. Treasury and for businesses investing in cap-

ital goods. The subsidies may also increase the price

of housing if home buyers use the savings on their

mortgages to bid more for houses. This study does

not include estimates of most of those indirect bene-

fits or costs because they are not directly related to

the size or distribution of the subsidies to the GSEs,

which is the focus of this analysis.

Direct Benefits from

Special Legal Status

The law treats the GSEs as instrumentalities of the

federal government, rather than as fully private enti-

ties. They are chartered by federal statute, exempt

from state and local income taxes, exempt from the

Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC’s) reg-

istration requirements and fees, and may use the Fed-

eral Reserve as their fiscal agent. In addition, the

U.S. Treasury is authorized to lend $2.25 billion to

both Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and $4 billion to

1. Because investors value the perceived protection from credit risk,

its value is already largely reflected in the estimate of the borrowing

advantage on debt and MBSs. In any event, the estimated exposure

under current law would be small because there is no explicit com-

mitment to cover losses. More generally, the estimated exposure

would depend on assumptions made about the strength and extent

of any implicit guarantees.

14 FEDERAL SUBSIDIES AND THE HOUSING GSEs May 2001

the FHLBs. GSE debt is eligible for use as collateral

for public deposits, for unlimited investment by fed-

erally chartered banks and thrifts, and for purchase

by the Federal Reserve in open-market operations.

GSE securities are explicitly government securities

under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and are

exempt from the provisions of many state investor

protection laws. Those advantages have not been

granted to any other shareholder-owned companies.

Some of those provisions of law result in direct mon-

etary savings to the GSEs, estimates of which are

reported below.

Indirect Benefits That Lower

Borrowing Costs

The special treatment of GSE securities in federal

law signals to investors that those securities are rela-

tively safe. Investors might reason, for instance, that

if the securities were risky, the government would not

have exempted them from the protective safeguards it

put in place to prevent losses of public and private

funds. This implied assurance appears to outweigh

the explicit disavowal of responsibility in every pro-

spectus for GSE securities.

2

The GSEs therefore en-

joy lower financing costs than would private finan-

cial intermediaries, were they to hold similar levels

of capital and take comparable risks.

3

As a consequence of those provisions, GSE ob-

ligations are classified by financial markets as

“agency securities” and priced below U.S. Treasuries

and above AAA corporate obligations. The super-

AAA rating reduces borrowing costs for the GSEs, in

part by promoting institutional acceptance of the se-

curities. Decisions by portfolio managers to invest in

GSE securities do not have to be justified in terms of

credit risk. General acceptance of the securities in-

creases investors’ willingness to buy them and en-

hances their liquidity. Those characteristics of ac-

ceptability and liquidity contribute to the relatively

high price investors are willing to pay for GSE secu-

rities. CBO assumes that those advantages are cap-

tured in its estimate of the spread between the rates

on GSE debt and the rates on comparable debt from

other financial institutions, so CBO makes no sepa-

rate estimate of the value of liquidity.

4

The Subsidy to Mortgage-

Backed Securities

A similar combination of federal regulatory provi-

sions and implied guarantees enhances the credit

standing, market acceptance, and liquidity of MBSs

guaranteed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. For

example, risk-based capital requirements for banks

are lower for GSE-guaranteed MBSs than for pri-

vately guaranteed MBSs. Federal backing also en-

ables Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to offer a credit

guarantee that the market perceives as more valuable

than any similar guarantee by a private company.

The enhanced quality of the guarantee reduces the

rate of return that investors require on GSE-guaran-

teed MBSs below the rates required on similar pri-

vately guaranteed MBSs. That lower rate permits a

mortgage pooler to pay higher prices for mortgages

and pass along lower interest rates to borrowers.

That competitive advantage on GSE-guaranteed

MBSs also enables Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to

charge higher guarantee fees than private guarantors.

2. A typical disclosure from a Fannie Mae prospectus states, “The

Certificates, together with interest thereon, are not guaranteed by

the United States. The obligations of Fannie Mae are obligations

solely of the corporation and do not constitute an obligation of the

United States or any agency or any instrumentality thereof other

than the corporation.”

3. See Congressional Budget Office,

Government-Sponsored Enter-

prises and the Implicit Federal Subsidy: The Case of Sallie Mae

(December 1985) and Douglas O. Cook and Lewis J. Spellman, “A

Taxpayer Resistance, Guarantee Uncertainty, and Housing Finance

Subsidies,”

Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics

,” vol.

5, no. 2 (1992), pp. 181-195.

4. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have argued that the greater liquidity

is the result of operating efficiencies rather than a subsidy. To the

extent that this viewpoint is correct, the estimate of their subsidies

will be biased upward. However, the large financial institutions

with which they are compared also manage their debt to enhance its

liquidity.

Estimating the Subsidies

C

BO has estimated the total subsidy derived

from the special relationship that the GSEs

have with the federal government by combin-

ing the benefits provided directly through specific

exemptions and privileges with the benefits of re-

duced borrowing costs and higher guarantee fees re-

sulting from the market’s reaction to their special

status. CBO has then divided that total subsidy be-

tween the portion retained by GSE shareholders and

stakeholders and the portion benefiting the conform-

ing mortgage borrowers who are financed by the

GSEs.

The Direct Benefits of

Regulatory and Tax

Exemptions

By CBO’s estimate, the savings from the exemption

from state and local income taxes, the exemption

from SEC registration, and the lower cost of obtain-

ing credit ratings for debt and MBS issues had a com-

bined value of about $1.2 billion in 2000 (see Table

4).

1

In general, the estimated value of those benefits

increases with the size of the GSE’s earnings. Other

special provisions of law, such as the right to use the

Federal Reserve as a fiscal agent or the line of credit

at the Treasury, may result in substantial savings to

the GSEs, but CBO has made no attempt to directly

estimate those savings here. Because investors value

GSE securities more highly as a result of those provi-

sions, some of their value is reflected in the borrow-

ing advantage on debt, which is calculated below.

The Subsidy to General

Obligation Debt Securities

The largest component of the total subsidy is the re-

duction in borrowing rates on the GSEs’ general obli-

gation debt securities. Estimating this rate differen-

tial requires comparing the rates paid by the GSEs

with the rates paid by comparable financial institu-

tions. Identifying a set of appropriate securities for

comparison is the first step in this calculation. Fac-

tors that CBO has taken into account include credit

rating, maturity, call features, and prevailing market

conditions.

CBO assumes that without GSE status, the

housing enterprises would have a credit rating in the

range of AA to A. That assumption is based on the

following:

o In 1997, Standard & Poor’s assigned a rating of

AA- to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac as a mea-

sure of their risk to the government. In Febru-

ary 2001, Standard & Poor’s again assigned a

rating of AA- to both agencies. The Federal

Home Loan Banks have not been rated on a

1. Consistent with CBO’s standard practices, all estimates are on a

before-tax basis.

16 FEDERAL SUBSIDIES AND THE HOUSING GSEs May 2001

Table 4.

Annual Value of Tax and Regulatory Exemptions for the Housing GSEs, 1995-2000 (In millions of dollars)

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000

Fannie Mae

State and Local Taxes 239.6 312.4 347.0 371.6 435.2 478.6

SEC Registration 55.3 79.4 70.7 139.7 122.2 85.0

Rating Fees 5.3

6.7 8.0 9.3 11.0 12.7

Subtotal 300.2 398.5 425.7 520.6 568.4 576.3

Freddie Mac

State and Local Taxes 126.9 143.8 157.1 188.5 252.9 282.7

SEC Registration 39.9 53.0 44.8 92.7 96.4 66.5

Rating Fees 5.3

6.7 8.0 9.3 11.0 12.7

Subtotal 172.1 203.5 209.9 290.5 360.3 361.9

FHLBs

State and Local Taxes 104.0 106.4 119.4 142.2 170.2 176.9

SEC Registration 41.6 42.5 49.6 83.9 68.0 50.4

Rating Fees 5.3

6.7 8.0 9.3 11.0 12.7

Subtotal 150.9 155.6 177.0 235.4 249.2 240.0

Total 623.2 757.6 812.6 1,046.5 1,177.9 1,178.2

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office.

NOTE: SEC = Securities and Exchange Commission.

comparable basis, but a higher credit rating for

them seems unlikely.

2

o Freddie Mac used an average of yields on AA

and A debt to calculate the funding advantage

for Freddie Mac and Fannie Mae in 1996.

3

o The U.S. Treasury assumed that Fannie Mae

and Freddie Mac would be rated A in a 1996

study, noting that the rating is typical of large

high-quality fully private financial firms hold-

ing portfolios of residential mortgages.

4

The assumed credit rating provides an essential

benchmark for estimating the subsidy to GSE debt.

The interest rates paid on securities issued by other

financial intermediaries and rated AA and A are the

rates that Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal

Home Loan Banks would probably pay on their debt

in the absence of the federal government’s implied

guarantee.

A recent study commissioned by CBO of securi-

ties issued from 1995 through 1999 is the basis for

2. See Congressional Budget Office,

The Federal Home Loan Banks

in the Housing Finance System

(July 1993). For instance, the qual-

ity of FHLB capital is lowered by the right of member banks to

redeem shares at par (the price they initially paid) in anticipation of

financial trouble.

3. See Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation,

Financing Amer-

ica’s Housing: The Vital Role of Freddie Mac

(June 1996), p. 33.

4. See Department of the Treasury,

Government Sponsorship of the

Federal National Mortgage Association and the Federal Home

Loan Mortgage Corporation

(July 11, 1996).

May 2001 ESTIMATING THE SUBSIDIES 17

the agency’s estimate of the GSEs’ borrowing advan-

tage on debt issues with an original maturity of more

than a year.

5

According to that study, the housing

GSEs paid significantly less on noncallable debt with

a maturity of greater than 300 days than banking in-

stitutions rated AA and A paid on comparable debt.

Several features of the estimates in that study require

further elaboration. The study’s authors calculated

yield spreads:

o Largely on the basis of market rates on the day

when a GSE or comparison security was issued

and, hence, most liquid;

o For noncallable, or “bullet,” debt only;

o By averaging observed spreads over the entire

estimation period; and

o On the basis of a sample of high-quality

national financial institutions.

Timing of Issues

By calculating yield spreads from observed rates on

securities on the day when the securities were issued,

this study avoids the errors that can be introduced

from using indices, matrix prices, or yields observed

on secondary-market trades. Bond indices mix old

and new issues and therefore combine liquid with

illiquid issues; matrix prices (prices based on interpo-

lations by market participants from current transac-

tions) introduce approximation error; and secondary-

market trading reflects the effect of a loss of liquidity

from the aging of securities and, more importantly,

does not reflect the interest rates that borrowers actu-

ally pay.

Spreads Based on Noncallable Debt

CBO attributes the same funding advantage to bullet

and callable GSE debt.

6

There are some logical and

practical reasons to treat those securities similarly,

although doing so arguably introduces a downward

bias into the estimated spread. Financial market par-

ticipants view callable debt as a combination of

straight debt and a call option and generally calculate

the value of callable debt using that type of decompo-

sition. Because the GSEs may have only a small ad-

vantage in the options market (owing to their higher

credit quality, which enhances liquidity), the prices

that they pay for options should be only slightly

lower than those paid by other market participants.

Thus, the advantage on the callable debt is likely to

be dominated by the subsidy on its straight debt com-

ponent. The practical reason for approximating the

funding advantage of callable debt by the estimated

advantage of bullet debt is that data on comparable

callable bonds are difficult to obtain. There are few

private issues available for comparison, and the more

complicated structure of callable bonds tends to add

noise to any estimate of yield differentials. In sum,

although attributing the same funding advantage to

callable and noncallable debt probably has led to an

understatement of the subsidy, CBO chose to rely on

an estimate based on more reliable data.

Long-Term Average Spreads

The spread between GSE and comparable private

securities varies over time. For instance, in times of

market stress, there may be a “flight to quality,”

which reduces rates on U.S. Treasury and GSE secu-

rities relative to private rates. An increase in demand

for safe, government-backed securities, therefore,

increases the gross subsidy to the GSEs and widens

the spread between rates on GSE debt and conform-

ing mortgages. Such episodes—two have occurred

since mid-1998—provide the GSEs with highly prof-

itable opportunities to increase their portfolio hold-

ings of mortgages, and they appear to have done so.

7

Although yield spreads observed during a short pe-

riod are useful in gauging current conditions, an aver-

age of spreads observed over a wide range of market

conditions is a more statistically reliable, as well as a

more conservative, indicator of the long-term benefits

of GSE status.

5. See Ambrose and Warga,

An Update on Measuring GSE Funding

Advantages

.

6. CBO’s 1996 estimates of the subsidy on GSE securities used a

higher subsidy estimate for the GSEs’ callable debt than for their

noncallable debt.

7. See, for example, Kenneth Posner,

Finance: Specialty and Mort-

gage

, Morgan Stanley Dean Witter, March 13, 2001, p. 5.

18 FEDERAL SUBSIDIES AND THE HOUSING GSEs May 2001

In fact, although the historical spread fluctuates,

it shows no apparent trend over time. On the basis of

that observation, CBO assumes that the spread was

fixed over the estimation period and going forward

will equal the average observed spread in the past.

With the supply of Treasury securities shrink-

ing, however, the demand for GSE debt securities

may rise in the future, further widening the spread

between GSE rates and those paid by AA and A

banking institutions. Furthermore, using a time-aver-

aged spread without adjusting for changes in the

amount of debt issued over time neglects the fact that

the GSEs tend to increase debt issuance when spreads

are high and decrease debt issuance when spreads are

low.

They also adjust the volume of MBSs and debt

in response to changing market conditions. A more

accurate measure of the federal subsidy, therefore,

would calculate the funding advantage as the average

of observed spreads weighted by the volume of secu-

rities issued at each spread. That approach would

increase the contribution of the most favorable ob-

served spreads to the “average” benefit. Alterna-

tively, the funding advantage could be permitted to

vary for each period. However, the variance of the

estimated spreads is often large relative to the year-

to-year changes in the advantage. Accordingly, CBO

uses the unweighted average of observed funding

advantages for the period even though doing so is

likely to undervalue the benefits of GSE status.

Comparison Sample

The funding advantage for the housing GSEs is cal-

culated by comparing rates on GSE debt with rates on

debt issues from a sample of 70 large national finan-

cial institutions, eight of which were rated AA+, AA,

or AA- and 62 of which were A+, A, or A-. Both

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have obtained a hypo-

thetical rating of AA- under the assumption that they

would operate as they do currently and would hold an

unchanged amount of capital if they were fully pri-

vate. The FHLBs have not received a comparable

rating but it appears unlikely that they would receive

a higher rating than Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac or a

rating lower than A. Thus, all three GSEs are within

the range covered by the sample.

The hypothetical AA- rating for Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac lies between the A and AA ratings of

those comparison firms. Very few AA-rated finan-

cial firms are available to be included in a compari-

son sample because most financial companies find it

advantageous to operate in a way that results in an A

rather than an AA rating on their long-term debt.

Taken together, the handful of private AA financial

institutions issued fewer than four comparable bonds

in four of the five years studied; and in one of those

years, there were no comparable AA issues. Infer-

ences about funding advantage drawn from such a

small sample would be subject to large errors.

Hence, CBO chose to base the analysis on the

broader sample.

8

CBO also performed a sensitivity

analysis based on the full sample of firms, giving

equal weight to the small number of AA issues and

the large number of A issues. This weighting re-

duced the estimated funding advantage on debt by

considerably less than the bounds reported in the sen-

sitivity analysis in the last section of this study.

The Subsidy Rate on Effective

Short-Term Debt

The rate reduction on GSE securities may vary with

the maturity of the security issued, in part because

default risk is lower over a short horizon than over a

longer time period. Even though the Ambrose and

Warga study found no systematic pattern in spreads

as a function of maturity for debt issues with a matu-

rity of more than 300 days, spreads could be lower

for issues with a shorter maturity. For example, a

study commissioned by Freddie Mac estimates the

advantage on short-term debt to be between 10 and

20 bps, relying on index value data.

9

Accordingly,

CBO uses an estimate of the spread on effective

short-term debt of 15 bps.

Determining the fraction of effective short-term

debt issued by the GSEs is not a straightforward cal-

8. This approach follows Freddie Mac’s own example in calculating

the GSEs’ funding advantage based on both A and AA issues in its

report

Financing America’s Housing: The Vital Role of Freddie

Mac

.

9. See James Pearce and James C. Miller III, “Freddie Mac and Fannie

Mae: Their Funding Advantage and Benefits to Consumers” (pre-

pared for Freddie Mac, January 9, 2001), available at

www.freddiemac.com/news/analysis/pdf/cbo-final-pearcemiller.pdf.

May 2001 ESTIMATING THE SUBSIDIES 19

culation because of their extensive use of derivative

securities such as swaps, which effectively transform

short-term borrowing into long-term borrowing and

vice versa. In order to calculate the

effective

quantity

of the GSEs’ short-term debt, their positions in deriv-

ative securities also must be analyzed. That informa-

tion is not publicly available, nor would it be easy to

interpret if it were. However, Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac report that the percentage of total debt

that was effectively short-term after “synthetic exten-

sion” at year-end 1999 was, respectively, 13 percent

and 7 percent.

10

Those amounts contrast with the

figures for nominal short-term debt of 41 percent and

49 percent reported on their respective balance

sheets. Percentages of effective short-term debt re-

ported for earlier years are higher—between 20 per-

cent and 30 percent. In its estimate, CBO sets the

fraction of effective short-term debt at 20 percent, in

line with past practice but weighted toward current

practice, and assumes that it remains at 20 percent

going forward in time.

11

Computation of an Average Spread

CBO estimates an overall funding advantage of 41

basis points on all GSE debt securities. A weighted

average, the estimate considers effective short-term

debt to be 20 percent of outstanding debt and to have

a 15 bp advantage, and effective long-term debt to be

80 percent of outstanding debt and to have a 47 bp

advantage.

Converting Yield Spreads

to Subsidy Values

CBO’s calculation of the total benefit from lower

borrowing costs employs a methodology designed to

capture the total subsidy associated with new credit

extended in a given year, or the “capitalized sub-

sidy.” It contrasts with a “subsidy-flow” calculation,

a single-year subsidy calculated by multiplying the

reduction in borrowing costs by the total amount of

outstanding GSE debt, which CBO used in its 1996

study.

As a measure of the federal benefit and its

change over time, the subsidy-flow methodology suf-

fers significant shortcomings. First, it recognizes

subsidies conferred today only gradually over many

years, rather than in the year that the commitment to

funding is made. Second, it records subsidies today

for funding from years earlier. When GSE debt is

priced and sold, the benefits of a lower interest rate

are secured for each year the financing is expected to

be outstanding, not just for the current year. Simi-

larly, a mortgage borrower locks in the benefit of

lower rates over the life of the mortgage. The sub-

sidy flow, therefore, understates the value that has

been transferred by the government in the current

year, while including some of the benefits of previous

years’ transactions. A more timely measure would

recognize all of the current and future benefits of this

year’s transactions but exclude subsidies from past

commitments.

A related shortcoming of the subsidy-flow mea-

sure is bias: downward when the GSEs are growing

rapidly, upward when they are expanding slowly. In

recent years, the debt issued by the housing GSEs has

been growing at an annual rate of more than 20 per-

cent, although that growth slowed to 12 percent in

2000. Throughout this high-growth period, the

subsidy-flow method would have underestimated the

size of the benefits conferred. Conversely, if the

GSEs were to stop growing, the subsidy-flow mea-

sure would continue to show net new subsidies to the

GSEs, even though they would primarily be receiving

deferred benefits from past transactions.

10. As an example of the synthetic extension process, a GSE may bor-

row $100 million by issuing a one-year security and intend to main-

tain that $100 million outstanding over five years using a succes-

sion of one-year securities. That short-term borrowing is trans-

formed to long-term borrowing using an interest rate swap. Under

the swap contract, the GSE agrees to make five years of fixed-rate

interest payments based on a $100 million principal value in ex-

change for receiving five years of floating rate payments. The GSE

can use the floating rate payments received from the swap to pay its

obligations in the one-year market and in effect it is left with a

fixed-rate interest obligation.

11. CBO assumes that the funding advantage on effective long-term

debt equals the funding advantage on original-issue long-term debt.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac have asserted, to the contrary, that the

funding advantage on synthetically extended debt is no greater than

that on short-term debt because the GSEs have no advantage in the

swap market. If so, however, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac finance

the synthetically extended portion of their debt at only a 15 bp ad-

vantage, when a 47 bp advantage is available on otherwise similar

securities that they could issue. Although it is possible that Fannie

Mae and Freddie Mac do not always choose the most advantageous

funding, such behavior is implausible in the face of such large rate

differentials. Accordingly, CBO’s estimates of the funding advan-

tage are based on the assumption that the GSEs fully exploit their

funding advantage.

20 FEDERAL SUBSIDIES AND THE HOUSING GSEs May 2001

CBO's decision to use the capitalized subsidy

measure is also consistent with the objective of the

Credit Reform Act of 1990, which is to recognize and

disclose the costs of long-lived credit transactions

when the commitment to that assistance is made.

Through law and generally accepted accounting prin-

ciples, the federal government requires that the pres-

ent value of all future benefits conveyed by new

loans and guarantees issued in the current year be

recognized.

12

The subsidy estimates here differ in

some respects from the treatment of financial guaran-

tees under the Credit Reform Act to reflect that there

is no explicit guarantee to the GSEs. Instead, the cal-

culations closely follow private-sector capital budget-

ing practices, which were similarly designed to re-

flect the present value of future commitments.

The more forward-looking approach to measur-

ing subsidies adopted in this study has been recom-

mended by several observers.

13

That method can be

illustrated by a familiar example. If a home buyer

obtains a 30-year fixed-rate $100,000 mortgage at

7.75 percent, rather than 8 percent, the first year’s

savings is $250 (0.25 percentage points times

$100,000). But the borrower will also enjoy interest

savings each year thereafter until the mortgage is

paid off. The sum of lower interest payments in all

years is sometimes (incorrectly) used as the savings

from the lower mortgage rate, but that figure over-

states the benefit to a borrower because it treats a

future dollar saved as equal in value to a dollar saved

today.

14

To adjust for differences in the value of

money over time, future interest savings must be dis-

counted with an appropriate interest rate. Capitaliza-

tion refers to the process of discounting and summing

annual benefits.

Although the basic procedure is straightforward,

its use raises the question of the life of the subsidy

benefit. The GSEs finance mortgages with initial

maturities that are usually 15 or 30 years but that may

be shorter, with debt ranging in maturity from a few

days to 30 years. Maturing or prepaid mortgages are

almost always replaced with new mortgages, extend-

ing the effective life of the subsidy.

CBO has considered two maturity horizons—

seven years and perpetuity—that provide lower and

upper bounds, respectively, for the subsidy estimates.

However, to link the subsidy more explicitly to the

mortgages acquired or guaranteed in a given year, all

subsidy estimates reported in this study use the lower

bound estimate unless otherwise indicated.

15

That

maturity is considerably shorter than the 15- or 30-

year term of a typical new mortgage because a large

fraction of mortgages are paid off early through refi-

nancing or the sale of houses. Because the GSEs

structure their debt financing to match expected mort-

gage cash flows, it is reasonable to expect that the

borrowing advantage on debt is also locked in on av-

erage over that seven-year period.

16

For the seven-year horizon, incremental borrow-

ing in a given year has two components. One compo-

nent is the increase in the total debt that is outstand-

ing. The second component is an estimate of new

mortgages that are replacing mortgages maturing in

the current year, called the “rollover amount” (which

is absent when the maturity horizon is considered to

be perpetuity). The subsidy estimate therefore re-

flects the average life of new mortgages acquired in a

given year, incorporating the sum of new growth and

the rollover of maturing mortgages. To calculate the

rollover amount, CBO assumes a distribution of life-

times for new mortgages and uses this distribution to

12. Credit Reform Act of 1990 and Statement of Federal Financial Ac-

counting Standards 2.

13. Robert S. Seiler Jr., “Estimating the Value and Allocation of Fed-

eral Subsidies to Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac” (paper presented at

the American Enterprise Institute conference “Fannie Mae and

Freddie Mac: Public Purposes and Private Interests,” Washington,

D.C., March 24, 1999), revised April 1, 1999, and Alden L. Toevs,

“A Critique of the CBO’s Sponsorship Benefit Analysis” (report

submitted by First Manhattan Consulting Group to Fannie Mae,

September 6, 2000).

14. A dollar in 30 years is equivalent to only $0.23 today because $0.23

invested at 5 percent today would grow to $1 in 30 years.

15. Over time, the anticipated average life of a mortgage varies because

of variations in the interest rate environment that affect prepayment

rates. In recent years, the average life of a typical mortgage has

been less than seven years. Using seven years as the basis for the

subsidy calculations is conservative, however, because the high

probability that maturing mortgages will be replaced by new mort-

gages implies a much longer effective life of new commitments.

16. Conceptually, the focus is on the life of the mortgages financed,

rather than on the life of the supporting debt, because mortgage

borrowers are the intended beneficiaries of the estimated subsidy

and that subsidy is received over the life of the mortgages. The

average maturity of liabilities rather than of assets could be used to

determine the subsidy horizon and would lead to similar results.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac maintain that their interest rate risk is

limited by their hedging strategies. Accordingly, the effective ma-

turity of their liabilities is close to that of their assets.

May 2001 ESTIMATING THE SUBSIDIES 21

Table 5.

Subsidies to GSE Debt, 1995-2000 (In billions of dollars)

1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000

Capitalized Subsidies

a

Fannie Mae 1.7 1.5 1.8 3.2 3.3 3.6

Freddie Mac 0.8 1.1 0.8 3.3 2.4 2.4

FHLBs 1.2

1.1 2.0 2.6 4.5 2.8

Total 3.7 3.7 4.5 9.1 10.2 8.8

SOURCE: Congressional Budget Office.

a. The subsidies to GSE debt are present values.

update the assumed maturity distribution of debt-

financed mortgages.

17

An assumption of perpetual life for new obliga-

tions implies only that the GSEs’ assets do not de-

cline over time.

18

If there is no growth, the GSEs

retire individual securities as they come due and issue

new securities to replace those that are maturing. In

fact, GSE securities consistently have shown year-

over-year increases in recent decades,

19

while the

overall conventional mortgage debt secured by one-

to four-family houses has increased every year in the

United States since World War II. The continuous

addition of new stock and the rollover of existing

properties ensure that even without inflation, total

mortgage debt will grow. If the GSEs merely main-

tained a constant share of housing finance, they

would grow indefinitely, as this case assumes.

The capitalized subsidy is calculated in two

steps. First, the annual incremental benefit is ob-

tained by multiplying the net increase in debt out-

standing during a year plus any assumed rollover of