Lijun Chen | Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago

Dali Yang | University of Chicago

Qiang Ren | Peking University

October, 2015

Report on the State

of Children in China

Report on the State of

Children in China

Lijun Chen

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago

Dali Yang

University of Chicago

Qiang Ren

Peking University

Recommended Citation

Chen, L.J., Yang, D.L., & Ren, Q.

(2015). Report on the State of Children

in China. Chicago: Chapin Hall at the

University of Chicago

Contact

Lijun Chen, Ph.D.

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago

1313 East 60th Street

Chicago, IL 60637

Phone: 773.256.5140

Email: [email protected]

Report on the State

of Children in China

Lijun Chen

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago

Dali Yang

University of Chicago

Qiang Ren

Peking University

October, 2015

Acknowledgements

In preparing this report, we were fortunate to have received generous nancial support from the Joint Research Fund

(Award No. 2014-003 “State of the Child in China”), established by Chapin Hall and the University of Chicago to

support collaborative research between the two institutions. We thank the Institute of Social Survey at Peking University

for permitting us to use data from the 2010 China Family Panel Studies. We also gratefully acknowledge nancial

support from the Confucius Institute at the University of Chicago.

We owe special thanks to Fred Wulczyn, senior research fellow at Chapin Hall, for his guidance and advice throughout

the whole project. Without his contribution we would not have been able to carry out this study. We would also like to

thank Yinxian Zhang and Yuanqi Wang for excellent research assistance with the data analysis and literature review.

We presented our preliminary ndings at the “Workshop on the State of China’s Children,” held at the University of

Chicago Center in Beijing in July 2015. We are indebted to the Center and its superb team for their assistance. We wish

to thank the participants of the workshop, especially Ming Wen (University of Utah), Zhixin Du (China Development

Research Foundation), and Danhua Lin (Beijing Normal University) for their insightful comments and fellowship.

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... 2

Signicance of the Study ........................................................................................................................................2

Multiple Contexts of Child Well-being ..................................................................................................................3

Data and Methodology ..........................................................................................................................................4

Overview ................................................................................................................................................................7

2. Laying the Groundwork: National Environment and Policy Context .........................................................................8

e urban rural divide and the hukou system ..........................................................................................................8

e urbanization drive, migrant population, and rural family structure ................................................................. 9

Family planning policy and family structure .........................................................................................................10

School consolidation and dwindling child population in rural areas .....................................................................11

3. Economic Well-being ...............................................................................................................................................12

4. Physical Health ........................................................................................................................................................15

5. Psychological and Social-Emotional Well-being ........................................................................................................19

6. Educational Achievement and Cognitive Development ............................................................................................23

7. Family and Community Contexts ............................................................................................................................29

8. Association of Family and Social Contexts with Child Development ........................................................................ 36

9. Conclusion and Policy Implications .........................................................................................................................43

References .....................................................................................................................................................................47

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

2

1. Introduction

Significance of the Study

According to the 2010 China Population Census data, the country is home to 222.6 million children between the ages

of zero and 14, accounting for 16.6% of the total population in mainland China (National Bureau of Statistics of China,

2011). Since the early 1980s, the living conditions and environments of Chinese children have changed dramatically due

to rapid industrialization, massive urbanization, and a stringent family planning policy (see World Bank, 2015a).

On the one hand, with industrialization and economic development, the economic conditions and physical well-being

of Chinese children have generally improved. is is especially true for children in rural areas where tens of millions of

parents can earn extra income from industrial or service jobs other than agriculture (NWCCW, NBS, & UNICEF, 2014).

Meanwhile, China’s family planning policy that allows one child for each urban couple and at most two for a rural couple

has led to smaller family size. is has helped boost the economic resources and emotional cherishment for the single child

to the extent that they are treated by their families like “little emperors” (Rosenzweig & Zhang, 2009).

However, the unbalanced economic growth in recent decades has also posed serious challenges for the well-being of

children, especially those in rural areas. Four challenges especially stand out. First, economic disparity between rural and

urban areas has remained and even increased in this period. e urban per capita disposable income has been over three

times the rural per capita net income (National Bureau of Statistics [NBS], 2011). In 2012, 128 million Chinese people,

mostly rural residents, were still living in poverty with an annual per capita income of less than 2,300 Yuan (equivalent to

1.6 USD per day) (China Academy of Sciences, 2012). e income gaps between urban and rural areas have contributed

to rural-urban disparities in child care and educational resources available to children. Second, multiple researchers

have identied various developmental decits for migrant children (Wang & Zou, 2010). Due to exclusionary policies

and practices against migrant laborers in many municipalities, children of migrant workers have diculty attending

local public schools and gaining access to other public services (Chan, 2009). e relatively meager income, poor living

conditions, and housing instability of most migrant laborers have also put their children at a disadvantage in comparison

to their urban counterparts.

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

3

ird, exclusionary policies imposed in many urban areas have forced migrant laborers to leave their children behind in

rural homes. In 2010, there were 61 million children who were left behind in rural areas, 22 percent of all children in

China (NWCCW, NBS, & UNICEF, 2014). Previous research shows long periods of parental absence may adversely

aect the psychological, social, and cognitive development of children, leading to problems such as low self-esteem,

depression, and lack of motivation at school, among others (Wen & Lin, 2012; Xiang, 2007). Without proper adult

supervision, left-behind children are also more likely to be victimized (Chen, Huang, Rozelle, Shi, & Zhang, 2009).

Fourth, other government policies and practices in some rural regions – particularly the consolidation of rural schools –

have exacerbated the plight of many rural children. is policy is blamed for the fact that children living in remote areas

have diculties accessing education.

e conditions of Chinese children, especially left-behind children and migrant children, have caused great concern

among government administrators and the general public. ere have been plenty of journalistic reports on the plight

of rural children. In addition to media coverage, many organizations and scholars, both in China and abroad, have

conducted academic studies and research on the socioeconomic conditions of children in China and their developmental

outcomes. ey have also made policy recommendations to address the developmental disparities between rural and

urban areas and improve the well-being of children (Xiang, 2007; All-China Women’s Federation, 2013; New Citizen

Program, 2014; Zou, Qu, & Zhang, 2005).

Despite the many studies of the situation of children in China, most of them are focused on a limited number of aspects

of child development without providing a full picture of children’s conditions. For instance, in terms of child well-

being, ocial government reports only present limited indicators, such as infant mortality, physical health, and school

enrollment, while social-emotional well-being indicators and other subjective well-being indicators – such as self-esteem

and sense of happiness – are absent. Besides, most studies on child well-being are based on non-representative samples

drawn only from a few regions and certain age groups. erefore, their ndings cannot be generalized to the whole child

population at a national level.

Our study, which is based on nationally representative household survey data, strives to oer a comprehensive view of

the conditions of today’s children in China. In this report, we cover all major domains of child development, including

children’s physical health, mental and psychological well-being, social well-being, and their cognitive and educational

development. Our report focuses on examining the developmental disparities between children of rural and urban

regions and between children who have dierent living arrangements (for instance, between left-behind children and

migrant children). We also strive to reveal variations in the ecological contexts of these children (i.e., the dierent

conditions of their families and communities that may have contributed to their dierent developmental trajectories).

Hopefully our eorts will help identify the most vulnerable groups of children in China and their developmental decits.

Our eorts to nd the risk and protective factors in these children’s social contexts may also help government agencies

and other stakeholders to formulate and implement targeted policies and programs to promote child well-being.

Multiple Contexts of Child Well-being

Scientic research in child development has long recognized the importance of living environments and nurturing

relationships for the healthy development of children (Bronfenbrenner, 1979; Shonko & Phillips, 2000). Early childhood

experiences in multiple contexts – such as families, peer groups, schools, and communities – will have a profound long-

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

4

term impact on children’s development and well-being. Typically, children spend most of their infancy and toddlerhood

with parents and other caregivers at home. erefore, aside from economic resources of the family, a nurturing relationship

with caregivers and a cognitively stimulating home environment are essential to children’s social and cognitive development

(Conger, Conger, & Martin, 2010). Child care institutions and schools are also major venues where children learn

important social and emotional skills as well as academic knowledge (Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schelling,

2011; Reynolds, Temple, & Ou, 2011). ese skills formed in the school years are essential for children to become

constructive members of society when they grow up. One last major social context in which children learn to interact is the

neighborhood. Neighborhood social norms, collective ecacy, safety, poverty level, and access to social service facilities are

all important to the well-being of children and their caregivers alike (Sampson, 2003).

Given the close relationship between living environment and well-being, children of lower socioeconomic status often

face multiple disadvantages. Without eective policy interventions, the toxic environments of these vulnerable children

will have a serious impact on their short-term development and long-term well-being. erefore, this study aims to

understand various aspects of social contexts, such as family functioning and community quality, that may contribute to

the developmental decits of vulnerable children in China. We pay special attention to the rural-urban disparities in child

well-being, describing the developmental decits of rural children, especially left-behind and migrant children, in contrast

to their urban counterparts. We also examine the family and social contexts of the children to reveal various factors that may

have contributed to the rural-urban disparities of child well-being.

Data and Methodology

is study is based on the 2010 baseline wave of the China Family Panel Studies (CFPS). Designed and administered by

Peking University, CFPS is a longitudinal survey of a nationally representative sample of nearly 15,000 families.

1

It adopts a

stratied three-stage cluster sample design where over 600 urban and rural communities are selected. From each community,

25 households are chosen at random (see Xie, Qiu, & Lu, 2012). Data are collected for all sample communities and all

members of sample households, including family members who are migrant workers. e 2010 CFPS has complete data for

8,990 children between the ages of zero and 15 years old, including caregiver reports for all children and direct interviews

with children between 10 and 15 years old. Information collected includes outcomes on major domains of child well-being

such as physical health, social-emotional development, cognitive development, and educational achievement. Contextual

information includes family living conditions, poverty level, parent education and employment, parenting behavior,

community contexts, and other areas. e wealth of information on children provides us with the opportunity to achieve a

comprehensive understanding of the development and well-being of the children in China.

Due to the complex sampling design and oversampling of children in some strata, the 2010 CFPS data introduce

a population weight variable that accounts for sampling design, nonresponse, and post-stratication adjustment

(Lu & Xie, 2013). In order to depict an unbiased and accurate picture of the conditions of children in China,

we decided to use the survey data analysis methods that take into account the survey design eect and unequal

population weights. e statistical analysis software we used is Stata/SE 12, and we applied Stata’s survey data

analysis commands in all of our analysis (Stata Corp, 2013).

1 Six provinces, Hainan, Inner Mongolia, Ningxia, Qinghai, Xinjiang, and Tibet, are not included in the sample for various reasons. Four of the

regions are in remote border regions and Hainan is a small island province located in the South China Seas. Together they make up only 5 percent

of the total population in China.

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

5

We conducted univariate and bivariate analysis to examine the child well-being outcomes in dierent social and familial

contexts and analyze the associations between them. We also adopted multiple linear and logistic regression methods to

understand the unique contribution of demographic and contextual factors to child well-being outcomes.

e basic demographic information of the sampled children grouped by urban and rural community type is shown in

Table 1.1. e grouping of communities as rural or urban is based on whether the sampled community is reported by

the village administrator as a Village Committee (

村委会) or Urban Resident Committee (居委会). As shown in the

table, 27 percent of the sampled children are living in urban communities. Our estimate of the urban population is

conservative compared to the estimate of the National Bureau of Statistics, which, based on dierent criteria, identies

half of the population as urban. Our estimate is more in line with the residence registration (hukou) status of the children

since it captures most of the 24 percent of children with urban hukou but excludes most children with rural hukou.

Based on their family structure, number of parents living at home, and community type, we further categorized the

sample children into ve groups: children in rural intact families (with both parents married and at home), urban intact

families (with both parents married and at home), children left behind by one or both parents (both parents married

but only one or no parent at home), migrant children without local hukou (both parents married), and single-parent or

no-parent children (parents divorced, or one or both parents died or unknown). As shown in Table 1.1, 67 percent of

all children live in intact families with both parents married and living together with the child. e left-behind children

are concentrated in rural communities because their father or mother (or both) have left home to work in urban areas.

ey number over 49 million, or 21 percent of all children in China.

2

Migrant children are those whose hukou is not

within the local county or district where they currently live with their parents. ey are called migrant children because,

most probably, their parents have migrated to the current community in search of jobs and brought the children along.

Our analysis indicates that over 16 million children are those who have migrated to new communities with their parents,

nearly 7 percent of all children.

3

While 60 percent of the migrant children live in urban areas, the remaining migrant

children live in rural communities. e last group of children (about 5%) is single- or no-parent children because one or

both parents have died or their parents are divorced and no longer living with the children. Nearly two-thirds of these

children live in rural areas.

2 According to the report by National Bureau of Statistics of China(2105), the 2010 Census identies 69.73 million children aged zero to 17 as left-

behind children, taking up nearly 25% of the child population in China. If we count in the children from single/no parent families whose parents

have migrated to work, our estimate is similar to the census report.

3 e 2010 Census data indicates that the total number of migrant children zero to17 years old numbered 35.81 million, about 12 percent of the

total child population(see Duan, Lu, Wang, & Guo,2013). If we exclude about 38 percent of the children that migrate within a county/district

and exclude the children who are 16 or older, the total number of migrants will be nearly 17 million, which is similar to our estimate based on the

CFPS data. Since the CFPS data we can access does not provide information on within-count migration, we cannot identify children who have

migrated within counties/districts.

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

6

Table 1.1 Characteristics of Children in Rural and Urban Areas in China

Rural Urban Total

Characteristic % n % n % N

All children 73.1 6,795 26.9 2,195 100 8,990

Child age

0 to 5 37.0 2,526 34.1 817 36.2 3,343

5 to 10

31.2

2,068 31.8 681 31.4 2,749

10 to 15

31.8

2,201 34.1 697 32.4 2,898

Gender *

Female

45.1

3,189 47.4 1,049 45.7 4,238

Male

54.9

3,606 52.6 1,146 54.3 4,752

Ethnicity *

Ethnic minority 19.1 940 9.9 188 16.6 1,128

Han ethnicity 80.9 5,855 90.1 2,007 83.4 7,862

Hukou Registration *

Urban hukou 7.6 584 69.0 1,533 24.1 2,117

Rural hukou 92.4 6,211 30.9 662 75.9 6,873

# of Parents at Home *

None 15.0 1,001 7.9 174 13.1 1,175

1 parent 15.5 1,126 12.7 268 14.8 1,394

2 parents 69.5 4,668 79.4 1,753 72.1 6,421

Residence Type *

Rural intact family 67.1 4,494 0.0 0 49.0 4,494

Urban intact family 0.0 0 66.6 1,463 17.9 1,463

Left-behind children 24.8 1,744 12.0 265 21.4 2,009

Migrant children 3.7 273 15.4 344 6.8 617

Single/No parent family 4.4 284 6.0 123 4.8 407

Total 100.0 6,795 100.0 2,195 100.0 8,990

Note: 2010 CFPS child sample N=8,990. Percentages are weighted; counts are unweighted.

* p < .05 based on designed-based Pearson chi square statistic.

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

7

Overview

Including this introductory section, this report has nine sections. In Section 2, we provide a general overview of the

national environment and policy context for the development and well-being of the children. We describe the hukou

system, the urbanization process, the family planning policy, and school consolidation, and discuss their implications for

child well-being. Sections 3 through 6 address dierent domains of child well-being outcomes in rural and urban areas

and by residence type. Section 3 covers the economic well-being of children in China, including family poverty level and

living conditions. Section 4 describes the children’s physical health, including incidences of low birth weight, sickness and

hospitalization, and overweight and obesity. In Section 5, we address the psychological and social well-being of children,

such as sense of happiness, depression, self-esteem, social skills, and number of good friends. Section 6 analyzes children’s

cognitive development and educational outcomes. We examine the proportion of children in kindergarten and schools

in rural and urban areas as well as their study performance, vocabulary and math test scores, and school satisfaction.

Section 7 examines the family and community contexts of children, including family structure, parenting behavior,

and community resources. In Section 8, we detail a series of multiple regression models we ran to estimate the eects of

dierent aspects of family and social contexts on child development. Section 9 summarizes our ndings and points out

their major policy implications for promoting the welfare of children in China.

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

8

2. Laying the Groundwork:

National Environment and

Policy Context

ough child well-being and development is a universal concern, each country faces unique challenges, including those

presented by the cultural and political context. In China, the most inuential contexts are the hukou system and the

country’s controversial family planning policies. ese institutions have posed specic challenges to child development in

China, as we describe below.

The urban rural divide and the hukou system

Established in the late 1950s during the heyday of central planning policy, thehukousystem is the Chinese household

registration system that categorizes an individual resident as a “non-agricultural resident” (居民) in an urban area or an

“agricultural resident” (农民) in a rural area. Hukou ties people’s access to public services and welfare such as education,

employment, and healthcare to their residential status, leading to an entrenchment between rural and urban residents

(Chan & Zhang, 1999; Wang, 2005, 2010). Urban residents are entitled to a range of social, economic, and cultural

benets that rural residents cannot receive, creating an underclass for rural residents. is has led to high income

inequality between rural and urban residents and posed great barriers for residential and social mobility of rural residents.

e hukou-based governance system has largely limited rural migrant workers’ access to services and welfare in urban

areas, including education, health care, pensions, and life insurance. While they can move freely to seek jobs, they

cannot settle down with full urban resident status, full rights as citizens, and unlimited access to public services and

social welfare services. eir children are denied access to urban public schools, and oftentimes have to be left behind

in the countryside. Even in urban areas where migrants outnumber local residents and contribute tremendously to local

economic growth, the distribution of public resources is only intended for local hukou residents (Xiang, 2007).

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

9

As a response to the increasing social problems, the hukou system has been gradually reformed since the 1990s.

“Temporary urban residency permits” for migrant workers to work legally in cities were launched in the 1990s. Since

2001, reform measures by various local governments have further weakened the system due to the overwhelming number

of rural residents working in cities and their contribution to urban economy. But these reforms have not fundamentally

changed the system. Hukou continues to contribute to China’s rural and urban disparity (Chan & Buckingham,

2008). On December 4, 2014, the Legal Aairs Oce of theState Councilreleased a draft residence permit regulation

intending to abolish the hukou system in small cities and towns. e implementation is ongoing and the eect of this

latest policy remains to be seen.

The urbanization drive, migrant population, and rural family structure

Despite the rural-urban divide created by the hukou system, China experienced rapid industrialization and urbanization

in the last two decades. According to the NBS, by the end of 2013, 53.7 percent of the total population lived in

urban areas, up from 26 percent in 1990. e massive transfer of rural workforce from countryside to cities has greatly

contributed to this dramatic jump (Ren, 2013).

4

However, due to the hukou barriers discussed above, few of the

migrants can obtain permanent urban citizenship that oers benets of, for instance, government-provided housing and

children’s education (Chan & Buckingham, 2008). Besides institutional discrimination, in cities there is also cultural

and individual discriminationagainst people with ruralhukou (Jin, Wen, Fan, & Wang, 2012). erefore, most migrant

workers and their families can hardly settle down in cities. According to the NBS, there were 168 million rural-urban

migrant workers by the end of 2014. Around 130 million workers migrated alone and only 35 million migrated with

families (National Bureau of Statistics of China, 2015); women and children are often left behind in the countryside,

leading to the prevalent split households in rural areas (Guo & Huang, 2014; Ma, Xu, Qiu, & Bai, 2011; Ye, Wang, Wu,

He, & Liu, 2013; Zhang & Zeng, 2013).

Given this context, the children of migrant workers have been largely disadvantaged, whether they are migrant children

in urban cities or children left behind in rural areas. According to the All-China Women’s Federation (ACWF, 2013),

by the end of 2010, there were around 35.8 million rural-to-urban migrant children between ages zero and 17. ey are

faced with many institutional and cultural barriers to living in their new homes, most important being limited access to

education. In general, migrant children face formidable barriers to enrolling in local public schools (Pong, 2014). With

a few exceptions, migrant children can be admitted to local schools as long as they pay extra fees, which most migrant

families cannot aord. Even if migrant children can aord an urban school, they have to return to their hukou registered

place to take the entrance examination for a higher level of education. However, what children have learned in their

schools may be substantially dierent from what is taught and tested in the hukou residence, making it dicult to enroll

in a higher level of education (Ding, 2012; Xiang, 2007). Aside from educational barriers, migrant children also suer

from other problems, including emotional diculties such as low self-esteem and loneliness, behavioral problems such as

smoking and drinking, and physical health problems such as a higher prevalence of infectious diseases (Hu, Fang, & Lin,

2009; Luo, 2005; Zhang, Qin, & Wu, 2010).

Children who are left behind in rural areas also encounter many challenges. According to the All-China Women’s

Federation (2013), there were more than 61 million rural left-behind children in China at the end of 2010, 21.88

4 Besides the inux of immigrants, the en mass reclassication of many rural areas surrounding central cities and many rural towns as surban has also

raised the percentage of urban population (see Ren, 2013 for details).

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

10

percent of the total population of children. Unlike migrant children, the biggest challenge faced by left-behind children

is the absence of parents. As reported by the ACWF, 46.74 percent of the left-behind children are left behind by both

parents, of which 32.67 percent are living with grandparents, 10.7 percent are living with other people (relatives or

friends of their parents), and 3.37 percent are living on their own. While the money that migrant workers sent home may

increase household income, migration has led to a lack of parental support and supervision of children’s development.

Grandparents, as primary guardians, usually have low literacy skills and limited energy to educate and take care of

children. As a result, left-behind children are susceptible to subpar educational achievement, increased risky behaviors,

psychological diculties, physical safety problems, human tracking, sexual harassment, and other types of abuse (Chen,

et al., 2009; Pan, 2014; Zheng and Wu, 2014). However, there is also competing evidence indicating that parents’

migration is not necessarily detrimental to child welfare and development, mainly due to return transfers of income and

parents’ recognition of the importance of education after migrating to urban cities (Ren & Treiman, 2013; Wen & Lin,

2012; Fan, Su, Gill, & Birmaher, 2010). Simply put, parental migration has been an important factor in child welfare

and development of rural families for both left-behind and migrant children.

Family planning policy and family structure

In addition to internal migration, family planning policies in China have also had major inuence on child development.

Numerous studies have documented the eect of family structure and parenting style on child development. According to

Becker (1981), there is a strong negative correlation between the quantity of children and quality of their lives, indicating

that lower fertility may encourage people to increase their investments in children, including providing better education,

more parenting time, and more emotional and nancial supports. e impact of the controversial family planning policy,

also known as the “one-child policy,” on child development has been intensely debated over the last two decades. On one

hand, academic ndings support the positive eect of the quantity-quality tradeo brought about by the one-child policy

(Rosenzweig & Zhang, 2009). It is good for child well-being in terms of greater parental investment and more available

resources for children. On the other hand, single children in a family may be spoiled by parents who focus all their love

and money on them. Prior research has studied the psychological consequences experienced by children without siblings.

Despite mixed conclusions, there is evidence that single children tend to be self-centered, less independent, and less sociable.

As a result, they have been called “little emperors” in China (Liu, Wang, Yin, & Gu, 1988).

A more serious eect of the one-child policy is the change of the sex ratio at birth (SRB). According to the NBS

data, SRB in China peaked at 1.20 in 2008, indicating 120 newborn boys for every 100 newborn girls. At the end of

2014, the SRB is 1.16. Selective abortion of female fetuses prompted by the one-child policy has led to great gender

imbalance and a high surplus of men. is ratio is higher in rural areas where preference for boys is stronger and fetal

gender screening devices are easily accessible (Festini & de Martino, 2004). In urban areas, however, studies suggest that

daughters have beneted from the one-child policy: they have enjoyed unprecedented parental support because they do

not have to compete with brothers for parental investment (Fong, 2002).

e family planning policy that has been implemented for over three decades has led to the gradual decline of the

child population in both urban and rural areas. e dwindling number of school-aged children has triggered school

consolidation practices in many areas, with inadvertent consequences for child well-being, as we discuss next.

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

11

School consolidation and dwindling child population in rural areas

Besides the persistent challenges posed by migration and family planning policies, there has been a special challenge to

child well-being due to an educational policy change that began in the early 2000s: the launch in 2001 of “Adjustment

on the Layout of Rural Schools,” also called “rural school closures and consolidations.” is campaign aimed to close

a large portion of village primary schools and expand “central” schools located in townships and county seats. e

campaign was stopped in 2012 due to its controversial eects on child education.

e policy was formulated in response to the sharp decline of the school-age population in rural areas caused by the

one-child policy and rural-urban migration (Lei, 2010; Wan, 2009). e government also wanted to improve education

quality and equity by reallocating and centralizing education resources from failing village schools to “central schools”

(Fang & Liu, 2013; Xu, 2013). e direct outcomes of this policy were remarkable. In 2000, there were 440,000 rural

primary schools in China. Ten years later, this number had decreased to 230,000 – a decrease of over 50 percent (21st

Century Education Institute, 2013). On the positive side, the school consolidation policy may have partially achieved

its goals. It may have boosted educational eciency through economies of scale (Fan & Guo, 2009; Li, Zeng, & Yang,

2012) and improved education quality and promoted regional equity (Fang & Liu, 2013; Ma, Lu & Li, 2011). However,

school consolidation policy has also been attacked due to its adverse eect on rural children’s development.

ere are many examples of this adverse eect. First and foremost, education has become less accessible to students

living in remote areas, leading to increased dropout rates of rural students. Many studies reported that school relocation

strikingly increased the distance between students in remote areas and central schools in townships, leading to higher

transportation costs and higher safety risks (Chu & Zhang, 2012; Ke, Xu, & Zhang, 2015; Yi et al., 2012). Researchers

also argue that the policy has exacerbated the polarization between remote villages in the county periphery and urban

areas in the county core, increasing the potential for greater regional disparities. us, the claimed policy goal of

promoting equity in education was not achieved (Cai & Kong, 2014; Fan & Hao, 2011; Xu, 2013). To address the

problem, the Chinese government launched the “no tuition and no fee” national policy and also required central schools

to provide school shuttle services. However, the eect on school enrollment has been minimal (Xu, 2013).

National policy has also encouraged the construction of boarding schools in response to increasing distances between

school and home. However, due to a shortage of funding and human resources, many boarding schools in rural areas

suer from unsanitary and overcrowded living conditions. Besides, young children living far away from intimate

family members often suer from psychological problems due to the lack of family supervision and parental emotional

support (Cui, 2012). Taken together, unqualied boarding schools have detrimental eects on students’ physical and

psychological health and pose high risks in food and living safety for students (Chu & Zhang, 2012; Wan, 2009). In

addition, school consolidation has also led to giant classes in central schools with inadequate teachers and facilities, which

is detrimental to education quality (Fang & Liu, 2013; Tao & Lu, 2011).

Opponents of this policy also claimed that this campaign has caused a cultural crisis in rural communities. e closure

of village schools makes fragile village culture more vulnerable, leaving villages to suer further poverty and other types

of decline (Xiong, 2009; Zhao & Wu, 2015). Overall, the school consolidation policy has presented special challenges to

child well-being and development in the countryside, especially in remote rural areas.

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

12

3. Economic Well-being

Economic well-being refers to the material resources and conditions available to children in their immediate living

environment (such as in their families). While various aspects of economic well-being in family and social contexts

are not domains of child development, they do have major and direct impact on child development. Persistent family

economic hardship and early material deprivation not only aect children’s physical health – leading to problems such as

malnutrition and stunting of growth – but also lead to long-term detrimental eects on socioemotional, self-regulation,

and cognitive development due to their toxic inuence on family processes and parenting (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002;

Hamoudi, Murray, Sorensen, & Fountaine, 2014; Linver, Brooks-Gunn, & Kohen, 2002; Yeung, Linver, & Brooks-

Gunn, 2002). Eradicating extreme poverty is one of United Nation’s eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

5

Despite China’s rapid economic development for the past three decades, at the end of 2012 there were still nearly

100 million people living below the poverty line of 2,300 Yuan

6

per capita annual net income (World Bank, 2015a).

Furthermore, the poorest people are concentrated in poor rural communities that often lack basic health care facilities,

public hygiene, and infrastructure.

In this section, we examine the economic well-being of Chinese children, including the living conditions of children,

especially those living in poverty. We compare children living in rural and urban areas and discuss the extent of rural-

urban disparities in various aspects of economic well-being. We also examine the family economic status of children

of dierent residence types, including rural children who are left behind by one or both migrant parents and migrant

children living with their parents in urban areas.

5 See MDG’s website at: http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/.

6 e rural poverty line of 2300 yuan per year is equivalent to 1.6 USD per person per day based on Purchasing Power Parity exchange rate in 2005.

See NBS. (2015). Poverty Monitoring Report of Rural China 2015.

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

13

As shown in Table 3.1, over 20 percent of Chinese children live below the poverty line of 2,300 Yuan per capita (1.6 USD

per day at the 2005 PPP exchange rate). Less than half of the children live in households with access to tap water, clean fuel

for cooking, ush toilet, or trash collection service.

Table 3.1. Distribution of Children’s Family Conditions in Rural and Urban China in 2010

Community Type

Variables

Rural (%) Urban (%) Total (%)

Family in poverty*

24.4 8.9 20.2

House crowding 20.2

16.9 19.3

Tap water for cooking* 41.1

90.6 45.6

Clean fuel for cooking* 35.4 84.9 48.7

Use ush toilet* 23.3 76.6 37.7

Trash collection service* 22.4

89.7 40.5

Father education less than HS* 88.2 55.3 79.4

Mother education less than HS* 93.3 61.3 84.7

Father unemployed/not working

12.8 9.7 11.9

Note: CFPS child sample N = 8,990, results are weighted. * p < .05 based on design-based Pearson chi square statistic.

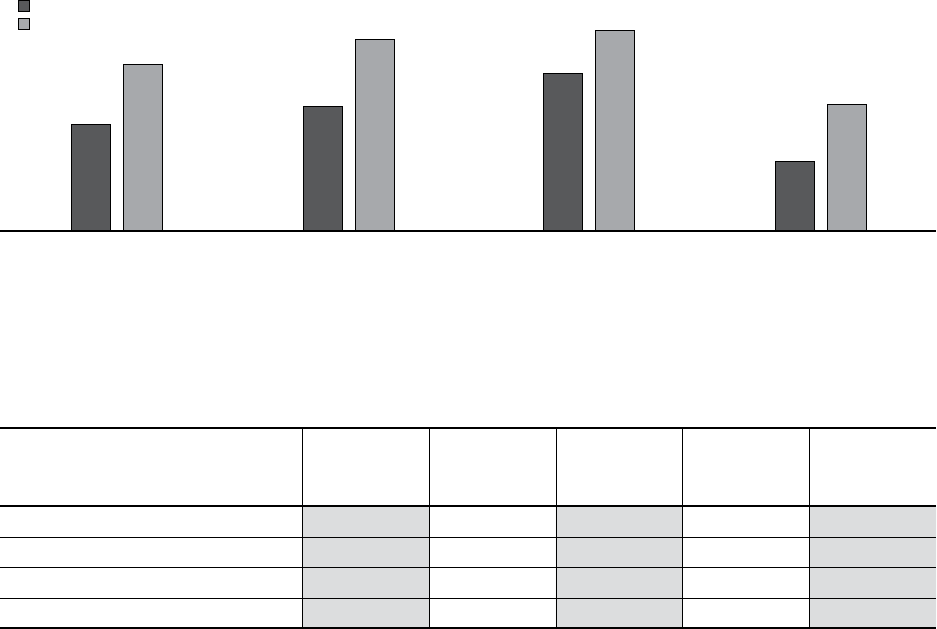

Furthermore, the rural-urban disparity in poverty level and living conditions is striking, as shown in Chart 3.1. While 9

percent of urban children live in poverty, over 24 percent of rural children live in poverty. e living conditions of rural

children are also much poorer with most rural families having no tap water, ush toilets, or trash collection service.

Chart 3.1. Family Conditions of Children in Rural and Urban China in 2010

Note: * p < .05 based on design-based Pearson chi-square statistic.

Source: CFPS (2010).

As shown in Table 3.1, the educational levels of children’s parents in China are fairly low. Seventy-nine percent of fathers

and 85 percent of mothers have no high school diploma. e rural-urban disparity is equally stark, with 88 percent of

rural fathers and 93 percent of rural mothers having less than high school education versus 55 percent and 61 percent

respectively for urban children (see Chart 3.1). In addition, a higher percentage of rural fathers are unemployed or not

working than urban fathers (13% versus 10%).

7

7 ose unemployed or not working only include people who clearly indicate they are not working or unemployed. Since all migrant workers and

those with unknown employment status are counted as employed, our estimate of the unemployment rate should be conservative.

Family in

Poverty*

House

Crowding

Tap Water for

Cooking*

Use Flush

Toilet*

Trash

Collection

Service*

Father

Education less

than HS*

Mother

Education less

than HS*

Father not

working

/ unemployed

24%

20%

41%

23%

22%

88%

93%

13%

9%

17%

91%

77%

90%

55%

61%

10%

Rural

Urban

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

14

A comparison of children in dierent residential types reveals that children in urban intact families have better family

nancial and living conditions as well as having a higher level of parents’ education (see Table 3.2). Although less well-o

than urban children, migrant children are still doing better than the other three groups of children: their family poverty

level is lower than that of children in rural intact families, left-behind children, and children in single/no parent families.

eir parents’ educational level is also higher. Left-behind children are similar to children in rural intact families in

family poverty level. ey report less house crowding, but a lower proportion of the left-behind children report using tap

water and clean fuel than rural intact families, probably due to the fact that most left-behind children are located in less

developed central and western regions of China. However, a higher proportion of the parents of left-behind children have

a high school education than parents of children in rural intact families. is is because parents of left-behind children

tend to be younger and have received more schooling.

Table 3.2. Percent Distribution of Children’s Family Conditions

by Residence Type in China in 2010

Variables

Rural

Intact (%) Urban (%)

Left

Behind (%) Migrant (%)

Single/No

Parent

Family (%)

Family in poverty* 23.6 6.6 23.9 11.8 31.9

House crowding * 20.9

15.7 16.6 20.1 26.9

Tap water for cooking* 44.3

91.3 40.0 71.8 59.8

Clean fuel for cooking* 39.3 85.0 33.8 72.4 42.6

Use ush toilet* 24.2 76.5 26.8 64.9 39.8

Trash collection service* 26.1

91.5 22.1 67.2 40.7

Father education less than HS* 88.5 51.3 84.1 70.9 82.8

Mother education less than HS* 93.5 58.4 89.6 75.0 85.1

Note: CFPS child sample N = 8,990, results are weighted.

* p < .05 based on design-based Pearson chi square statistic.

By far the most economically disadvantaged are children in single/no parent families. Nearly one third of these children

live in poverty, in contrast to 7 percent of urban children and 24 percent of children in rural intact families and left-

behind children who live in poverty. Children in single/no parent families are also more likely to report house crowding.

Although a higher percentage of their families use tap water, clean fuel, a toilet, and trash collection service, this is largely

because some single/no parent families live in urban areas where public utilities are more accessible.

e results described above reveal a glaring disparity between rural and urban children in various aspects of economic

well-being. Low parental educational attainment, unemployment or underemployment, low family income, and poorer

living conditions put rural children at a disadvantage and pose great risks for their development. Children from single/no

parent families in both urban and rural areas are the most economically disadvantaged.

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

15

4. Physical Health

Physical health refers to the biological status of children, including their overall physical functioning, incidence of disease

and hospitalization, age- and gender-appropriate body mass index (BMI), and healthy lifestyle (Moore et al., 2008).

Physical health is the foundation of children’s overall development and aects all other domains of child well-being. Physical

health indicators such as low birth weight, infant mortality rate, and malnutrition have long been the focus of the health

promotion policies and intervention programs in China (for instance, see Chinese Children Development Outline released

by State Council

8

). As indicated by ocial statistics, the physical status of children has greatly improved in the past half

century with the increasing availability of health care services and better living conditions (Meng et al., 2012).

is section describes the various aspects of physical health of children in China based on the 2010 CFPS survey data.

We cover the following indicators: the rate of low birth weight children, incidence of sickness and hospitalization, health

insurance coverage, overweight and underweight, and regular exercise behavior.

We dene low birth weight as a weight of 2.5 kilograms (5.5 pounds) or less at birth for the children. As birth weight in

the CFPS survey is reported by the caregiver instead of measured objectively, we restrict the sample to zero to three-year-

olds in order to minimize recall bias. Table 4.1 indicates that low birth weight children account for 8.5 percent of all zero

to three-year-olds. According to their caregivers, 30 percent of all children have been sick in the last month, and nearly

eight percent of all have been hospitalized in the last year. Medical insurance programs, most of them publicly funded,

are used by just 63 percent of children.

9

For healthy life style, we use self-reported frequency of physical exercise in the

past month as the indicator. As shown in the table, 72 percent of children between 10 and 15 years old have engaged in

physical exercise twice or more in the last month.

8 See “中国儿童发展纲要(2011-2020)” http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2011-08/08/content_1920457.html

9 Only 10 percent of the children have private or commercial medical insurance plans. Public health insurance programs include New Rural

Cooperative health care, urban employee health insurance, urban resident health insurance (see Chen, Jiang, & Huang, 2009).

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

16

e other major indicator of child physical soundness is the body mass index (BMI) which is a person’s weight in

kilograms divided by the square of height in meters. Since a high BMI often indicates high body fat, BMI can be used

to screen for weight categories such as obese or overweight that may lead to health problems. As there are no national

standards for BMI for age in China, we use the United States CDC’s child growth standards instead. We calculated

each child’s BMI percentile from its gender-specic BMI for age and classied the children as obese (≥ 95th percentile),

overweight (85th to 95th percentile), normal (5th to 85th percentile) and underweight (≤ 5th percentile).

10

As shown in Table 4.1, 19 percent of the children aged one to 15 years old are underweight, while eight and 18 percent

are overweight or obese, respectively.

11

Only 55 percent of all children in China have a BMI classied as “normal.” We

reiterate that body weight and height of the children used to calculate their BMI are reported by caregivers instead of

measured; therefore, some percentiles may not be accurate.

Table 4.1. Distribution of Children’s Health Conditions in Rural and Urban Areas

in China in 2010

Community Type

Variables

Rural (%) Urban (%) Total (%)

Low birth weight (age 0-3 years old) * 9.8 5.0 8.5

Sick last month 30.1 28.9 29.8

See doctor last year * 48.6 55.4 50.4

Hospitalized last year 7.3 8.7 7.7

Have medical insurance * 64.5 58.3 62.8

Self-reported health (10-15 years old) 73.0 74.3 73.4

Exercise last month (10-15 years old) 70.6 74.8 71.8

BMI Categories (1-15) *

Underweight 19.1 17.9 18.8

Normal 52.9 60.9 55.1

Overweight 8.1 9.0 8.3

Obese 20.0 12.2 17.8

Note: Sample sizes vary according to age group, results are weighted.

* p < .05 based on design-based Pearson chi square statistic.

10 See http://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/bmi/childrens_bmi/about_childrens_bmi.html.

11 In the US, among young people aged 2 to 19, about 31.8 percent are considered to be either overweight or obese

(http://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/health-statistics/Documents/stat904z.pdf). See also Ogden, Carroll, Kit, & Flegal, 2014.

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

17

ere is an obvious rural-urban disparity in low birth weight and child obesity. As shown in Chart 4.1, while 5 percent of

urban children aged zero to 3 have a low birth weight, nearly 10 percent of rural children do. Poverty, malnutrition, lack

of prenatal care, and poor living and working conditions of some rural families may have contributed to low birth weight

(Kramer, 1987). Additionally, rural children are more likely to be obese than urban children (20% vs. 12%).

12

Our nding

also shows that, although there are similar proportions of rural and urban children who get sick, rural children are less likely

to see a doctor than urban children. is is more likely due to a lack of availability of or access to medical services in rural

areas rather than a reection of their dierent health status. An encouraging nding for rural children is that 64 percent of

rural children have health insurance in contrast to 58 percent of urban children. is reects the achievement of the New

Rural Cooperative Medical Care that was launched in 2003 (Wagsta, Lindelow, Wang, & Zhang, 2009; World Bank, 2005).

Although the coverage and payment standards of the rural program are not as generous as the medical insurance types enjoyed

by many urban residents, it still can protect rural families from nancial devastation in case of severe illness and get children

the treatment they need (Fan, Xie, & Yin, 2009; Wang, Gu, Du, & Wang, 2007; Yao & Zhang, 2013).

13

Chart 4.1. Health Conditions of Children in Rural and Urban Areas in 2010

Note:* p<.05 based on designed-based Pearson chi square statistic.

DataSource: CFPS (2010)

12 is nding is dierent from some prior research ndings showing a lower percentage of rural children as obese than urban children

(e.g., Ministry of Public Health, 2012).

13 Studies also show that the New Rural Cooperative Medical Care increases use of preventive care, but does not lead to more use of formal medical

service or better health conditions (Lei & Lin, 2009).

Low

Birthweight

(0-3)*

Obese (1-15)* Sick Last Month See Doctor Last

Year*

Hospitalized

Last Year

Have Medical

Insurance *

Self-reported

Health (10-15)

Exercise Last

Month (10-15)

Rural

Urban

10%

20%

30%

49%

7%

64%

73%

71%

5%

12%

29%

55%

9%

58%

74%

75%

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

18

Table 4.2. Distribution of Children’s Health Conditions by Residence Type in China in 2010

Variables

Rural

Intact (%)

Urban

Intact (%)

Left

Behind (%) Migrant (%)

Single/

No parent

Family (%)

Low birth Weight (0-3 years old)† 9.1 4.6 9.9 5.9 28.5

Sick last month (0-3 years old) * 43.3 38.9 56.7 43.4 51.2

See doctor last year* 46.7 55.8 55.6 49.1 46.9

Hospitalized last year 6.9 8.1 9.0 8.5 7.4

Have medical insurance * 66.1 60.7 61.9 48.5 62.0

Self-reported health (10-15 years old) 73.6 73.4 73.9 71.5 71.3

Exercise last month (10-15 years old) 71.5 74.5 69.9 73.6 69.8

Note: Sample sizes vary based on age group. Results weighted. † .05< p < .10; * p < .05 based on design-based Pearson chi square statistic.

For children with dierent residence types (see Table 4.2), a major nding is that children left behind in rural areas are

much more vulnerable to illness than either rural or urban intact families as well as migrant children and those from

single/no parent families.

In fact, as many as 57 percent of the left-behind children between zero and three years old were reported to be sick in the

last month, compared to 43 percent, 39 percent, 43 percent, and 51 percent for normal rural, urban, migrant children

and single/no parent children, respectively. ey were also somewhat more likely to be hospitalized in the last year than

the other children and reported getting less physical exercise. Migrant children are less likely to have low birth weight

than rural intact and left-behind children, but they have the lowest percentage of public medical insurance coverage at

48 percent, compared to over 60 percent for any other groups of children. e health conditions of children in single/no

parent families are not much better than the left-behind children. Over half of them have been sick in the last month. As

many as 28 percent of these children are born with low birth weight, versus 10 percent of left-behind children.

In summary, rural children are at a disadvantage in many aspects of physical health. e most vulnerable children are the

largely rural, left-behind children and the children living in single/no parent families in both rural and urban areas.

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

19

5. Psychological and

Social-Emotional Well-being

Psychological well-being and social well-being are two separate, but related, developmental domains for children.

Psychological health refers to the mental and emotional state of children and their opinions about themselves and

their future. Indicators include self-esteem, self-ecacy, depression, and sense of happiness. Social well-being indicates

the ability and skills of children to get along with others and make friends in their social milieu. e two domains

are closely related because children with mental problems – such as depression, anxiety, and other emotional self-

regulation disturbances – often act out in socially undesirable ways, such as showing social withdrawal, aggressiveness,

and antisocial behaviors. Children and adolescents with mental health problems and social decits often have

diculty in normal cognitive development and school performance (see, for example, Breslau, Lane, Sampson, &

Kessler, 2008). e Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has been monitoring children’s mental health

in the US through various ongoing national surveys and registry systems.

14

Although no comprehensive national

statistics about children’s mental health state in China are available, various studies have examined dierent mental

health issues of children and youth in various regions of China (see, for example, Tang & Qin, 2015).

In this section, we examine the psychological well-being of 10- to 15-year-old children from several aspects, including

depression, sense of happiness, condence for the future, self-esteem, and self-ecacy.

15

e composite index of

depression comes from the adapted Chinese version of the K6 screening tool (see Green, Gruber, Sampson, Zaslavsky,

& Kessler, 2010). It consists of 6 questions asking respondents how often they experience each of six symptoms of

major depression and generalized anxiety disorder in the past month. In this study, depression is indicated when the

14 See: http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/su6202a1.htm?s_cid=su6202a1_w

15 Self-esteem and self-ecacy scales are only available for 10- year-old children.

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

20

child reports that he/she experiences at least one of the six symptoms at least 2 or 3 times per week. Happiness and

condence for the future are both based on single questions asking the respondents how happy they feel they are and

how condent they are in their future. Children who report a score of 4 or 5 on a ve-point Likert scale from very

unhappy (“1”) to very happy (“5”) or no condence at all (“1”) to very condent (“5”) are regarded to be “happy” or

“condent in their future.”

Self-esteem is based on the Chinese version of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale. Each child’s total score is the sum of

scores for each of 9 statements.

16

Higher scores indicate higher self-esteem.

17

Bandura (1989) dened self-ecacy as

the condence individuals have in their ability to organize and execute courses of action required to attain specic

performance outcomes. CFPS used the rst 4 items of the 7-item Pearlin Mastery Scale designed to measure the

perception of individuals for their ability to control forces that signicantly impact their lives. After reverse coding

three items, we summed the four items to get the self-ecacy score, with higher scores indicating higher self-ecacy.

18

To assess social well-being, we use three indicators that are based on three single questions asked of 10- to 15-year-old

children. ey are asked to assess their personal relations and their social skills on a ve-point Likert scale from 1 to 5,

with 1 representing “very bad” and 5 representing “very good.” Children who report a score of 4 or 5 on each of the

two scales are regarded as having good relations and social skills. e children are also asked to report the number of

good friends they have, which is a continuous variable.

16 One statement, “I wish I could have more respect for myself,” is excluded from the original ten because of the inaccurate translation in

the Chinese version.

17 e composite self-esteem scale has an unadjusted mean of 25.78 (sd = 2.24, min = 19, max = 35).

18 e composition self-ecacy scale has an unadjusted mean of 10.96 (sd = 1.38, min = 6, max = 15).

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

21

As shown in Table 5.1, 21 percent of the 10 to 15 years olds have depression symptom(s) more than two times a week,

20 percent do not feel happy, and 22 percent have no condence in their future. As shown in Chart 5.1, there are

signicant disparities between rural and urban children in their feelings of happiness and condence. A higher percentage

of rural children than urban children regard themselves as unhappy or have no condence in their future (22% versus

16% are unhappy, and 24% versus 19% have no condence in their future). e mean self-esteem and self-ecacy scores

of rural children are signicantly lower than urban children (Table 5.1).

Table 5.1. Psychological and Social Well-being for Children Ages 10 to 15 China in 2010

Variables

Rural Urban Total

Depression (%) 20.5 22.1 21.0

Don’t feel happy (%) * 21.6 16.4 20.1

No condence in future (%) † 23.5 18.7 22.1

Lack good personal relations (%) * 34.0 23.7 31.1

Lack good social skills (%) * 27.7 21.2 25.8

Self-esteem score (mean; age 10) * 25.4 26.9 25.9

Self-ecacy score (mean; age 10) * 10.8 11.5 11.0

Number of good friends (mean) * 6.2 8.3 6.8

Note:Sample size N=3,464. e means test is based on post-estimation test of means. † .05< p< .10;* p< .05 based on design-based Pearson chi square statistic.

e results on social well-being reveal that rural children lag behind their urban counterparts in all three indicators of social

well-being (Chart 5.1). Over a third of rural children report not having good personal relations, in contrast to a quarter of

urban children. Rural children have on average six good friends while urban children report an average of eight.

Chart 5.1. Psychological and Social Well-being of Children in Rural and Urban China in 2010

Note: *p< .05 based on design-based Pearson chi square statistic. † .05 < p < .10 based on design-based Pearson chi square statistic.

Source: CFPS(2010).

Depression Don’t Feel Happy * No Condence in

Future†

Lack Good Personal

Relations*

Lack Good Social Skill*

Rural

Urban

21%

22%

24%

34%

28%

22%

16%

19%

24%

21%

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

22

Children in dierent residence types also tend to dier in levels of psychological and social well-being. Table

5.2 shows that left-behind children and children of single/no parent families are the two groups vulnerable to

psychological ill health. Around 30 percent of the children of single/no parent families suer from symptoms

of depression and are unhappy. Both left-behind children and children of single/no parent families have lower

ecacy scores than children of rural and urban intact families. Children of single/no parent families are the most

disadvantaged in terms of social well-being. irty-eight percent report that they do not have good personal relations

in contrast to 33 percent of rural intact children and 23 percent of urban intact children.

Table 5.2. Psychological and Social Well-being for Children Ages 10 to 15

by Residence Type in China

Variables

Rural

Intact

Urban

Intact

Left

Behind Migrant

Single/

No Parent

Family

Depression (%) † 18.9 24.7 21.4 18.2 29.8

Don’t feel happy (%) † 20.3 17.7 20.1 16.4 30.7

No condence in future (%) 21.1 18.6 26.0 24.5 28.6

Lack good personal relations (%) * 33.4 23.0 33.6 22.5 38.0

Lack good social skills (%) 26.4 22.1 27.8 20.6 32.2

Self-esteem score (mean; age 10) * 25.5

a

26.9

ab

25.3

b

25.9 26.1

Self-ecacy score (mean; age 10) * 11.1

abc

11.5

adef

10.6

bd

10.8

e

10.2

cf

Number of good friends (mean) * 6.4

a

8.6

abc

6.0

b

7.6 6.5

c

Note: Sample size N=3,464. † .05< p < .10, * p < .05 for percentages based on design-based Pearson chi square statistic. * p < .05 for post-estimation test of

means. e categories with the same subscripted letters are signicantly dierent at p < 0.05 level.

On the other hand, migrant children are the least likely to report depression symptoms and feeling of unhappiness.

is is despite the fact that they are more likely to show no condence in their future than rural and urban intact

children. Additionally, migrant children are more likely to report having good personal relationships than any of the

other groups of children.

It is also noteworthy that, although children of urban intact families have the highest self-esteem and self-ecacy

scores, and are more likely to be happy and have condence in the future, they have a higher probability of reporting

depression symptoms than children of rural intact families, left-behind children, and migrant children. is nding is

contrary to the higher levels of social-emotional well-being for urban children in almost all other aspects, and warrants

further examination.

e results presented in this section demonstrate the rural-urban disparities in psychological and social well-being,

with rural children, left-behind children, and children of single/no parent families at a clear disadvantage.

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

23

6. Educational Achievement

and Cognitive Development

Educational and cognitive well-being refers to the ability of children to learn language, mathematics, and other

knowledge appropriate for their age level. It also includes their development of cognitive skills required to eectively

understand their environment and communicate with people. Kindergartens and schools are major formal settings

where children learn new knowledge and master various cognitive skills. It has been established that early childhood

education at high quality child care centers, preschools, and elementary schools are crucial for children’s later educational

achievement and future economic success (Cunha & Heckman, 2010; Heckman, Moon, Pinto, Savelyev, & Yavitz, 2010;

Reynolds, Temple, & Ou, 2011). Since the 1980s, with the implementation of the nine-year compulsory education

system, most children in China have been able to complete nine years of elementary and junior high school. Early

childhood education through public and private kindergartens and nurseries is also developing rapidly in both urban

and rural areas.

19

However, major challenges still remain in bridging the gap between rural and urban areas in terms of

available educational resources and the quality of school education (Dollar, 2007; Qian & Smyth, 2008).

is section describes the educational and cognitive well-being of children in China. We present the proportion of

children enrolled in kindergarten and schools and compare the levels of engagement in school, school satisfaction,

and school performance between rural and urban children. We also compare rural and urban children in their college

aspirations as well as their scores on math and vocabulary tests.

19 For instance, see the NBS “Report on Implementation of Chinese Children Development Outline” (2013年中国儿童发展纲要实施情况统计报告).

Available at: http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/201501/t20150129_675797.html

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

24

As Table 6.1 indicates, 55 percent of the 3-to 5-year-old children are in nursery or kindergarten. However, while 76

percent of urban children are enrolled in kindergarten, only 48 percent of rural children are enrolled (see Chart 6.1). is

clearly reveals the rural-urban discrepancy in early education resources for preschool-age children. Yet, the rural-urban

disparity in school enrollment is minimal; ninety-two percent of rural children age six to 15 and 94 percent of same age

urban children are enrolled in schools. e high enrollment rate of school age children reects the achievement of the

9-year compulsory education policy. However, nearly a third (31%) of 10- to 15-year-old students in rural communities

attend boarding schools, which are often of poor quality. In contrast, only eight percent of urban students aged 10 to 15

are boarders. Overall, as many as 64 percent of 10- to 15-year-olds aspire to complete a college education.

20

However,

there are signicant disparities in college aspirations of rural and urban students. While 77 percent of urban students

harbor college aspirations, only 59 percent of rural children do so (see Chart 6.1).

Table 6.1. Distribution of Child Schooling in Rural and Urban China in 2010

Community Type

Variables

Rural (%) Urban (%) Total (%)

In kindergarten (age 3-5) * 47.5 76.3 54.8

In school (age 6-15) 92.04 94.2 92.6

In boarding school (age 10-15)* 30.8 7.6 24.2

Aspire to college degree (age 10-15)* 58.7 77.0 63.9

Note: Sample size varies according to age group. Results weighted. * p < .05 based on design-based Pearson chi square statistic.

Chart 6.1. Schooling for Children in Rural and Urban China in 2010

Note: * p< .05 based on design-based Pearson chi square statistic.

Source: CFPS(2010).

20 “College education” as dened here includes two-year colleges (similar to associate degrees in the US), four-year colleges and post-graduate study.

In Kindergarten (age 3-5)* In School (age 6-15) In Boarding School (10-15)* Aspire to college degree(10-15)*

Rural

Urban

47.5%

92.0%

30.8%

58.7%

76.3%

94.2%

7.6%

77.0%

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

25

Table 6.2 shows the schooling status for children by residence type. Compared to children in the other residence types, fewer

left-behind children are enrolled in kindergarten or other preschool programs. Children of single/no parent families are less

likely to aspire to a college degree than other groups of children. Although migrant children lag behind urban children in

intact families in kindergarten enrollment and college aspiration, they perform much better on both aspects than children of

rural intact families, left-behind children, and children of single/no parent families.

Table 6.2. Child Schooling by Residence Type in 2010

Variables

Rural

Intact

Urban

Intact

Left

Behind

Migrant

Single/

No Parent

Family

In kindergarten (age 3-5) * 50.3 79.8 45.8 61.9 56.7

In school (age 6-15) 92.6 94.7 92.3 90.8 89.5

In boarding school (age 10-15)* 31.8 7.8 25.6 13.9 17.8

Aspire to college degree (age 10-15)* 60.2 78.7 60.4 69.2 53.3

Note: Sample sizes vary. Results weighted.* p < .05 based on design-based Pearson chi square statistic.

e data presented on study engagement are based on the average score of ve items asking students about their study

habits on a ve-point Likert scale from totally disagree (1) to totally agree (5): “study hard,” “pay attention to study in class,”

“double check homework after completion to guarantee correctness,” “obey school rules and disciplines,” and “don’t play

until completing homework.” School satisfaction is measured by the average score of ve items asking children about their

satisfaction with school, their head teacher, Chinese teacher, math teacher, and English teacher on a ve-point Likert scale

from very dissatised (1) to very satised (5). Satisfaction with study performance is measured by a single item (“How do

you think of your academic performance?”) on a scale from very dissatised (1) to very satised (5). Self-evaluation as a

student is measured by another single item (“How excellent do you think you are as a student?) on a scale from very bad (1)

to very excellent (5).

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

26

Chart 6.2 shows the mean scores of study engagement, school satisfaction, satisfaction with study performance, and

self-evaluation of rural and urban children by gender. For study engagement of children who are 10 to 15 years old,

although there are signicant gender dierences in favor of girls, no dierence is found between rural and urban

children. Comparing school satisfaction between rural and urban students, we do nd some signicant dierences.

Rural children, especially boys, are the least satised with their schools. Rural girls tend to like their schools better

than rural boys, but are less satised than urban girls with their schools. On the measure of self-evaluation as a

student, rural males also tend to be the least satised (also see table 6.3).

Chart 6.2. Study Engagement and Satisfaction for Children 10 and 15

by Gender and Community Type in China in 2010

Note: * p < .05 for post-estimation t-test of means for one or more two-category comparisons.

Source: CFPS (2010).

Table 6.3. Mean Scores of Study Engagement and Satisfaction for Children Aged 10 to 15

by Community Type and Gender in 2010

Rural Female Rural Male Urban Female Urban Male

Indicator Mean S.E. Mean S.E. Mean S.E. Mean S.E.

Study Engagement

3.676

ac

0.025 3.488

ab

0.027 3.679

bd

0.033 3.528

cd

0.034

School Satisfaction 4.029

ac

0.037 3.964

abd

0.036 4.267

bce

0.048 4.081

de

0.045

Satisfaction with

Study Performance

3.405

a

0.038 3.228

ab

0.031 3.418

b

0.051 3.319 0.065

Self-evaluation

as a Student

3.287

a

0.039 3.055

abc

0.040 3.319

b

0.055 3.237

c

0.068

Note: Sample size N=3,359. Results weighted.

e categories with same subscripted letters are signicantly dierent at p< 0.05 based on postestimation T test of means.

Rural Female

Rural Male

Urban Female

Urban Male

Study Engagement * School Satisfaction * Satisfaction with Study* Self-evaluation as Student *

3.68

3.49

3.68

3.53

4.03

3.41

3.23

3.42

3.32 3.29

3.06

3.32

3.24

3.96

4.27

4.08

Chapin Hall at the University of Chicago: Report on the State of Children in China October 2015

27

Table 6.4 shows the means of study engagement and school satisfaction by residence type. It is encouraging to nd

that both the left-behind children and migrant children are better able to engage in their studies than children in

rural intact families. However, migrant children are more satised with their schools than the left-behind children and

children of rural intact families. Left-behind children are also signicantly less satised than urban children with their

academic performance and self-evaluation as a student.

Children’s scores on the vocabulary and math tests administered directly by the CFPS survey interviewer are objective

measures of the cognitive ability of 10- to 15-year-olds. e vocabulary test is a cognitive test of language ability

designed by CFPS for recognition of Chinese words according to level of diculty. e math test is a test for children

and adults containing math skills questions based on levels of diculty.

21

Table 6.4. Mean Scores of Study Engagement and Satisfaction for Children Aged 10 to 15

by Residence Type