Acadia National Park

Channel Island National Park Dry Tortugas National Park

Washington Support Office

National Park Service

U.S. Department of Interior

NPS National Transit Inventory

and Performance Report, 2022

Rocky Mountain National Park

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report

Executive Summary

2022

This is a summary of the 2022 National

Park Service Transit Inventory and

Performance Report. This effort:

1. identifies NPS transit systems across the

country,

2. tracks the operational performance

(e.g., boardings) of each system, and

3. inventories NPS- and non-NPS-owned

transit vehicles and vessels and collects

detailed vehicle information.

26.6 Million

Passenger Boadings

81

Systems

Operated

52

Parks

Represented

790

Vehicles &

Vessels

*Reflects systems that operated

during the fiscal year 2022 only

Of the 81 transit systems that operated, the top 10 transit systems accounted for 82% of the

passenger boardings in 2022. The systems with over a million boardings are located at Statue of

Liberty National Monument, Zion National Park, Grand Canyon National Park, Alcatraz (Golden Gate

National Park), the National Mall Area, and Yosemite National Park.

The National Park Service owns vehicle fleets for 20 systems and operated 15 of those

systems in 2022. NPS-operated systems account for 594,369 passenger boardings—about 2% of total

boardings.

Purpose

(by % of transit systems)

Mobility to or

within Park

26%

Interpr

etive

Tour 36%

Critical Access

30%

Transportation

Feature 9%

Mode

(by % of transit systems)

Train, Trolley

<1%

Ferry Boat

39%

Shuttle,

Bus, Van,

Tram 60%

Aircraft <1%

Business Model

(by % of transit systems)

Service Contract

11%

NPS Owned and

Operated 19%

Cooperative

Agreement 19%

Concession

Contract 52%

2022

Executive Summary

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report

Executive Summary

F

E

45% of NPS-owned transit

vehicles operate on alternative

fuel, while 19% of non-NPS-owned

vehicles operate on alternative fuel.

81 NPS transit systems operated in fiscal year 2022.

Of those, 53 operated for six months or more and of

those, 26 operated year-round.

Passenger Boardings by Park

1 - 1,000

1,001 - 350,000

350,001 - 750,000

750,001 - 1,500,000

1,500,001 - 5,000,000

Performance Measures

Visitor Experience

The majority of the NPS-owned transit system vehicles and vessels are accessible for people

with mobility impairments. In 2022, 59% of NPS-owned vehicles are accessible to people with

mobility impairments (e.g., require a wheelchair lift).

Operations

The National Park Service partners with the private sector to provide the majority of transit

services. Non-NPS entities operate 76% of NPS transit systems, which account for 98% of

passenger boardings servicewide. The National Park Service owns and operates the remaining

24% of transit systems, which account for the remaining 2% of passenger boardings.

Environmental Impact

National Park Service transit systems mitigate vehicle emissions. The net CO

2

emissions savings

of the 820 transit vehicles and vessels evaluated (excluding planes, rail, snowcoaches, and vehicles

with incomplete data or that did not operate) was equivalent to removing 10.2 million personal

vehicle trips and 618 million passenger vehicle miles from the road.

Asset Management

National Park Service-owned vehicles and vessels have an estimated $151 million in

recapitalization needs between 2023 and 2032. Parks with estimated transit vehicle replacement

costs over $5 million during the next five years include Acadia National Park, Grand Canyon

National Park, Harpers Ferry National Historical Park, Isle Royale National Park, and Yosemite

National Park.

States

PB2019

0-1000

1001-350000

350001

750001

1500001-10000000

0

States

PB2019

0-1000

1001-350000

350001

750001

1500001-10000000

0

States

PB2019

0-1000

1001-350000

350001

750001

1500001-10000000

0

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 iv

This page intentionally blank.

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 v

Table of Contents

Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 1

Data Collection and Methodology .............................................................................................

2

Inventory Results ...............................................................................................................................

3

System Characteristics .................................................................................................................

4

Passenger Boardings ...................................................................................................................

8

Vehicles and Vessels ..................................................................................................................

12

Performance Measures ...................................................................................................................

16

Visitor Experience ......................................................................................................................

16

Operations ................................................................................................

.................................18

Environmental Impact ...............................................................................................................

23

Asset Management ...................................................................................................................

25

Next Steps ................................................................................................

........................................ 27

Appendixes ................................................................................................

...................................... 30

Appendix A – A

cknowledgments .............................................................................................30

Appendix B – Nat

ional Park Service Alternative Transportation Program Goals and

Objectives ............................................................................................................................31

Appendix C – D

efinition of Transit ..........................................................................................33

Appendix D – 202

2 NPS National Inventory System List .........................................................37

Appendix E – C

hange in Vehicle Types ....................................................................................43

Appendix F – V

ehicle Replacement Assumptions ...................................................................44

Appendix G – A

ir Quality and Emissions .................................................................................50

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 vi

List of Figures

Figure 1: Systems by primary purpose .............................................................................................. 5

Figure 2: Systems by vehicle mode ...................................................................................................

6

Figure 3: Fleet system ownership by business model ......................................................................

8

Figure 4: Passenger boardings by NPS region ................................................................................

10

Figure 5: Passenger boardings by mode ........................................................................................

11

Figure 6: Passenger boarding

s by business model.........................................................................12

Figure 7: Number of vehicles by fuel type .....................................................................................

13

Figure 8: All vehicles by age class (years) .......................................................................................

15

Figure 9: Accessibility of NPS-o

wned transit vehicles (entire fleet) .............................................18

Figure 10: Percent change in boardings from 2018 to 2022 .........................................................

19

Figure 11: Distribution of service duration by number of months ..............................................

20

Figure 12: Year-t

o-year comparison of reported accidents ..........................................................22

Figure 13: Annual CO

2

emissions ....................................................................................................24

Figure 14: Vehicle trips (in millions) avoided because of NPS transit systems.............................

53

Figure 15: Carbon dioxide emissions avoided (in metric tons) per regions ................................

.54

Figure 16: NPS transit system carbon dioxide emissions ...............................................................

56

Figure 17: NPS transit system nitrogen oxide emissions ...............................................................

57

Figure 18: NPS transit system volatile organic compound emissions ...........................................

58

Figure 19: NPS transit system carbon monoxide emissions...........................................................

59

Figure 20: NPS transit system PM

2.5

emissions ................................................................................60

Figure 21: NPS transit system PM

10

emissions ................................................................................61

List of Tables

Table 1: NPS transit systems changes between inventories (2018 to 2022) ................................... 3

Table 2: Systems by primary purpose ...............................................................................................

7

Table 3: Count methodology ............................................................................................................

9

Table 4: Passenger boardings for the 10 highest-u

se transit systems ............................................ 9

Table 5: Number of vehicles that operated in 2022 by fuel type .................................................

14

Table 6: Vehicle ow

nership by age class ........................................................................................14

Table 7: Comparison of systems and boardings from 2018 to 2022 ............................................

19

Table 8: Response to saf

ety and operational questions ...............................................................22

Table 9: Comparison of emission results ........................................................................................

23

Table 10: Distribution of miles and CO

2

emissions by vehicle ownership ....................................24

Table 11: Vehicle age for NPS transit vehicle types .......................................................................

26

Table 12: Recategorization of vehicle types ..................................................................................43

Table 13: Summary of vehicles on public lands .............................................................................

46

Table 14: Vehicle replacement costs (in 2021 dollars) and expected life for nonelectric

v

ehicles .............................................................................................................................................47

Table 15: Vehicle replacement costs (in 2021 dollars) and expected life for electric vehicles ...

48

Table 16: Recapitalization totals by year .......................................................................................

49

Table 17: Total transit system vehicle miles traveled and ferry hours by region ........................

52

Table 18: Diverted passenger trips and CO

2

emissions avoided ...................................................54

Table 19: Comparison of emission results ......................................................................................

55

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 vii

Cover Photos:

Island Explorer, Acadia National Park. Photo: NPS (upper)

Island Packers, Channel Islands National Park. Photo: NPS (lower left)

Dry Tortugas Ferry, Dry Tortugas National Park. Photo: NPS (lower right)

Executive Summary Photo:

Visitor Shuttle, Rocky Mountain National Park. Photo: NPS

As the nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has the responsibility for most of our

nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering sound use of our land and water resources;

protecting our fish, wildlife, and biological diversity; preserving the environmental and cultural values of our parks and

historic places; and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The department assesses our energy

and mineral resources and works to ensure that their development is in the best interests of all our people by encouraging

stewardship and citizen participation in their care. The department also has a major responsibility for American Indian

reservation communities and for people who live in island territories under U.S. administration.

909-188262 / F6335 / May 2023

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 viii

This page intentionally blank.

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 1

Introduction

The 2022 National Park Service (NPS) Transit Inventory and Performance Report communicates

the servicewide outcomes and status of NPS transit systems. This comprehensive listing has

been compiled annually in this format since 2012 and covers surface, waterborne, and airborne

systems. The inventory establishes a working definition of NPS transit systems for the purpose

of this document; helps the National Park Service comply with 23 United States Code (USC)

203(c),

1

which requires “a comprehensive national inventory of public Federal lands

transportation facilities”; and fulfills other internal needs.

The 2022 inventory is meant to assist the National Park Service with the following:

Measure NPS transit performance.

Capture asset management and operational information not tracked in current NPS

systems of record.

Integrate transit data with NPS systems of record, including asset management data in

the Financial and Business Management System for NPS-owned vehicles.

Inform the National Long Range Transportation Plan, regional long-range transportation

plans, and the Annual Accomplishments Report by providing key transit statistics, which

can also be used to track progress towards goals.

Comply with Executive Order 14057, “Catalyzing Clean Energy Industries and

Jobs Through Federal Sustainability,” with a goal of 100% zero-emission vehicle

acquisitions by 2035.

Communicate program information and projected vehicle recapitalization needs.

1

23 USC 203 Federal Lands Transportation Program: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/USCODE-2014-title23/pdf/USCODE-2014-

title23-chap2-sec203.pdf.

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 2

Data Collection and Methodology

Each year, the same definition of NPS transit systems is used to ensure consistent data collection

across the nation and over time. Only parks with systems that meet each of the following three

criteria listed below are included in this effort (see appendix C for more information).

1. The NPS transit systems move people by motorized vehicle on a regularly scheduled

service.

2

2. Th

e NPS transit systems operate under one of the following business models:

concessions contract; service contract; partner agreement, including memorandum of

understanding, memorandum of agreement, or cooperative agreement (commercial use

agreements are not included); or is NPS-owned and operated.

3

3. All routes and services at a given park that are operated under the same business model

by the same operator are considered a single NPS transit system.

The 2022 NPS transit inventory is limited to systems in which the National Park Service has

either a direct financial stake or committed resources to develop a formal contract or

agreement.

The following information was collected for the 2022 fiscal year:

transit system name and description

passenger boardings

business model

system purpose

system type/mode

system level safety metrics (accident occurrence and property damage)

vehicle information including fuel type, capacity, service miles, engines, horsepower,

accessibility, and age

owner and operator type (National Park Service or non-National Park Service) and

contact information

operating schedule

2

This criterion includes services with a posted schedule and standard operating seasons/days of week/hours. Services that do not

operate on a fixed route—charter services for individual groups or services that exist for the sole purpose of providing access to

persons with disabilities—are not included.

3

This report does not distinguish between a memorandum of understanding, memorandum of agreement, or cooperative

agreement. All are recorded as “cooperative agreement.”

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 3

participation of a local transit agency in the service

operational status (operated, did not operate)

4

Fo

r the 2022 inventory, 63 parks provided information on their transit systems. Some parks

report incomplete information because they do not track the requested service information or

they could not provide the information before the end of the data collection period. For the

purposes of this report, 81 of 101 identified transit systems operated in fiscal year 2022.

Nonoperating transit systems and associated vehicles have not been included unless specifically

stated.

Appendix D includes a full list of surveyed transit systems by region.

Inventory Results

Detailed findings of the 2022 inventory are presented in the Vehicle Inventory Statistics, System

Characteristics, and Passenger Boardings sections below.

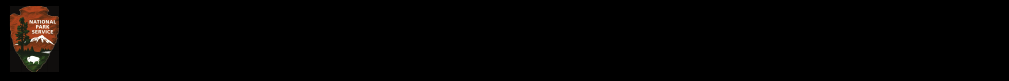

Table 1 summarizes the differences in key results of the NPS transit inventories over the last five

years.

Table 1: NPS transit systems changes between inventories (2018 to 2022)

Note: NPS=National Park Service

Source: 2018–2022 NPS transit inventory data

Key Findings 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Total Number of Systems

• Number of Systems that Operated

95

95

95

95

96

66

97

63

101

81

Number of Parks Represented 60 60 49 62 63

Passenger Boardings (millions)

• Excluding 10 Highest Ridership Systems

42.1

7.0

45.9

7.1

11.1

1.1

16.2

2.3

26.6

4.7

Number of Vehicles

• NPS-Owned Vehicles

• NPS-Owned Vehicles that Operated

• Non-NPS Vehicles

• Non-NPS Vehicles that Operated

976

281

695

835

236

599

673

149

524

865

269

215

596

508

874

274

244

600

546

Systems Operated by Local Transit Agency 9 9 3 5 5

5

4

Systems that did not operate but intend to operate in the future remained part of the inventory.

5

The DC Circulator, Giant Forest Shuttle, Fairfax Connections Wolf Trap Express, Hiker Shuttle (Delaware Water Gap National

Recreation Area), and Shuttle Transport (Harper’s Ferry) are the five systems that were operated by a local transit authority.

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 4

The Ford Island Bus Tour at Pearl Harbor National Memorial and Full Circle Trolley at Marsh-

Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park are the two systems added in 2022.

6

Additionally,

four systems returned to the inventory and two systems are no longer operating. In the NPS

2022 inventory, there are a total of 101 systems: 81 operated in some capacity, and 20 systems

did not operate. Nonoperational systems listed the COVID-19 pandemic, driver availability,

permitting, and other issues as the reasons they did not operate.

Passenger boardings increased by 10.5 million (39%), reflecting increased transit system

operations, visitation, and public use of transit systems. Visitation across the national park

system increased 5%; 312 million recreation visits were recorded in 2022 compared to 297

million recreation visits in 2021.

7

The increase in boardings indicates that visitors are less likely

to self-isolate because of COVID-19 and are returning to transit system use, if available.

System Characteristics

The 2022 inventory identified 81 operating systems in 52 parks. Figures 1 and 2 place these

systems in the context of the primary system purpose, mode, and business model. Results for

system characteristics in 2022 are similar to the results reported in 2021.

System Purpose

Park staff categorized each of their transit systems into one of the five following primary

purposes (figure 1):

29 systems are guided interpretive tours.

24 systems provide critical access to an NPS park or site that is not readily accessible to

the public due to geographic constraints, park resource management decisions, or

parking lot congestion.

21 systems provide mobility to or within a park as a supplement to private automobile

access.

7 systems are considered a transportation feature (a primary attraction of the park).

None of the systems that operated are primarily designed to meet the accessibility needs

of a visitor with special needs.

6

The four systems that returned to the inventory include: Concession Shuttle (North Cascades National Park), Ferry Service (Dry

Tortugas National Park, Fort Pickens Tram Service (Gulf Island National Seashore); systems no longer operating: Ajo Mountain

Drive Tour (Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument) and Roosevelt Ride (Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site).

7

In 2022, the National Park Service received 312 million recreation visits, up 15 million visits (5%) from 2021. While not as high as

2018 and 2019 (318 million and 327 million recreation visits, respectively), servicewide visitation has essentially recovered to pre-

pandemic levels. The year 2022 is very much like years immediately before the NPS centennial in 2016 and is only 6% lower than

that all-time record year.

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 5

Figure 1: Systems by primary purpose

Note: N=101 systems; DNO=did not operate

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

Special Needs, 1 systems DNO, 1%

Interpretive Tour,

29 systems operated,

28%

Interpretive Tour,

9 systems DNO, 9%

Critical Access,

24 systems operated, 24%

Critical Access,

3 systems DNO, 3%

Mobility to or within Park,

21 systems operated, 21%

Mobility to or within Park,

2 systems DNO, 2%

Transportation Feature,

7 systems operated, 7%

Transportation Feature,

5 systems DNO, 5%

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 6

Mode

The 2022 transit inventory identified four modes operating in NPS transit systems. Most of the

transit systems are shuttle/bus/van/tram systems (43 systems, 43%), followed by ferry/boat (32

systems, 32%), train/trolley (4 systems, 4%), and plane (2 systems, 2%) (figure 2).

Figure 2: Systems by vehicle mode

Note: N=101 systems; DNO=did not operate

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

Business Models

NPS transit systems operate under one of four types of business models (table 2, figure 3).

Concession Contracts: In 2022, 42 of the transit systems operated through concession

contracts in which a private concessioner pays the National Park Service a franchise fee

to operate inside a park. Five concession contract systems used vehicle fleets exclusively

owned by the National Park Service. Two systems have a mixed ownership fleet.

Service Contracts: Transit systems that are owned and/or operated by a private firm use

service contracts. In 2022, nine transit systems operated under a service contract. Out of

the nine service contract systems, four service contract systems used vehicle fleets

owned by the National Park Service.

Aircraft, 2 systems

operated, 2%

Shuttle/Bus/Van/Tram,

43 systems operated,

42%

Shuttle/Bus/Van/Tram,

16 systems DNO, 16%

Ferry/Boat,

32 systems

operated, 32%

Ferry/Boat,

3 systems DNO, 3%

Train/Trolley,

4 systems operated, 4%

Train/Trolley, 1 system DNO, 1%

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 7

Cooperative Agreements:

8

Fifteen transit systems operated under an agreement in

2022. None of those systems are owned by the National Park Service.

NPS Owned and Operated: In 2022, the National Park Service owned vehicle fleets for

20 systems and operated 15 of those systems.

9

These owned-and-operated systems tend

to be small and provided critical access to a park or park site, were interpretive tours, or

provided service for special needs.

Table 2: Systems by primary purpose

Notes: N=101 systems; DNO=did not operate; NPS=National Park Service

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

System Purpose

Concession

Contract

Cooperative

Agreement

NPS Owned and

Operated

Service

Contract

Total

Critical Access

12 1 DNO 4 0 5 0 3 2 DNO

24 3 DNO

Interpretive Tour

21 6 DNO 4 0 3 3 DNO 1 0

29 9 DNO

Mobility to or within Park

4 1 DNO 6 0 6 1 DNO 5 0

21 2 DNO

Special Needs

0 0 0 0 0 1 DNO 0 0

0 1 DNO

Transportation Feature

5 2 DNO 1 0 1 0 0 3 DNO

7 5 DNO

Total

42 10 DNO 15 0 15 5 DNO 9 5 DNO 81 20 DNO

8

The National Park Service Alternative Transportation Program uses “cooperative agreement” as a general term, encompassing all

qualifying partner agreements (memorandum of understanding, memorandum of agreement, and cooperative agreement).

9

The National Park Service maintained ownership of vehicle fleets for 36 systems in 2022. Twelve systems with NPS-owned vehicle

fleets were idle in 2022.

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 8

Figure 3: Fleet system ownership by business model

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

Passenger Boardings

In 2022, over 26.6 million passenger boardings occurred across all NPS transit systems.

10

If the

81 operating systems were considered one enterprise and compared to public transit agencies

across the country, its boardings would be comparable to transit systems in Minneapolis,

Minnesota.

11

Excluding concession contracts and cooperative agreements, NPS-owned and

operated systems and service contract systems reported 11.5 million trips (43% of total

boardings) in 2022.

Parks use various methodologies to count boardings. Most systems indirectly record passenger

boardings through ticket sales (10.1 million) and manual counts (8.5 million). Estimated,

automated, and other counter methodologies account for the remaining approximately 8

million passenger boardings.

10

A “passenger boarding” or “unlinked trip” occurs each time a passenger boards a vehicle. This is an industry-standard measure

used in the Federal Transit Administration’s National Transit Database.

11

“Public Transit Ridership Report Third Quarter 2022.” American Public Transportation Association. November 22, 2022.

Retrieved February 7, 2023. https://www.apta.com/wp-content/uploads/2022-Q4-Ridership-APTA.pdf.

5

4

15

5

4

3

35

6

15

5

2

2

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

Concession

Contract

Concession

Contract DNO

Cooperative

Agreement

NPS Owned and

Operated

NPS Owned and

Operated DNO

Service Contract Service Contract

DNO

NPS Non-NPS NPS/Non-NPS

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 9

Table 3: Count methodology

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

Count Methodology

Number of Systems Passenger Boardings

Ticket Sales 41 10,141,488

Manual 29 8,535,240

Automatic 6 6,366,313

Estimated 3 1,411,324

Other 2 190,500

A

pproximately 82% (21,973,922 million) of boardings on NPS transit systems in 2022 are

attributable to 10 systems (table 4). Two systems from the 2021 top 10 list did not make the top

10 list in 2022.

12

The Giant Forest Shuttle (Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks) and Island

Explorer & Bicycle Express (Acadia National Park) are new to the top 10 list in 2021. Boardings

increased in 2021 for eight of the 10 top 10 systems.

Table 4: Passenger boardings for the 10 highest-use transit systems

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

Rank

Park System Name

2022

Boardings

Business Model System Purpose

1 STLI Statue of Liberty Ferries 6,993,087 Concession Contract Critical Access

2 ZION Zion Shuttle 4,383,151 Service Contract Critical Access

3 GRCA South Rim Shuttle Service 4,348,518 Service Contract

Mobility to or within

Park

4 GOGA Alcatraz Cruises Ferry 1,327,939 Concession Contract Critical Access

5 NAMA DC Circulator 1,201,986 Cooperative Agreement Transportation feature

6 YOSE Yosemite Valley Shuttle 1,015,082 Concession Contract

Mobility to or within

Park

7 PERL USS Arizona Memorial Tour 766,055 Cooperative Agreement Interpretative Tour

8 SEKI Giant Forest Shuttle 733,477 Cooperative Agreement Critical Access

9 ROMO

Rocky Mountain National Park

Visitor Shuttle

618,464 Service Contract

Mobility to or within

Park

10 BRCA

Bryce Canyon Shuttle and

Rainbow Point Shuttle

586,163 Service Contract

Mobility to or within

Park

Notes: BRCA=Bryce Canyon National Park; GOGA= Golden Gate National Recreation Area; GRCA=Grand Canyon National Park;

NAMA=National Mall and Memorial Parks; NPS=National Park Service; PERL=Pearl Harbor National Memorial; ROMO=Rocky Mountain

National Park; SEKI=Sequoia & Kings Canyon National Parks; STLI=Statue of Liberty National Monument; YOSE=Yosemite National Park;

ZION=Zion National Park

12

The Grand Canyon Railway (Grand Canyon National Park) and Island Explorer & Bicycle Express (Acadia National Park) were

not in the top 10 list in 2022.

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 10

High-ridership shuttle systems are typically provided via service contracts, concession

contracts, and cooperative agreements. A greater proportion of the water-based systems are

provided through concession contracts and either provide critical access to parks and park sites

or serve as interpretive tours.

The National Park Service partnered with five local transit agencies in 2022 those partnerships

accounted for just 2 million passenger boardings in that year.

13

Passenger boardings among

NPS-owned and operated systems (15 systems) accounted for 594,369 passenger boardings.

Interior Regions 6, 7, and 8 and Interior Region 1 each reported more than 5 million passenger

boardings in 2022, exceeding other regions. Interior Region 1 – National Capital Area and

Interior Regions 8, 9, 10, and 11 reported more than 1 million passenger boardings. However, if

the 10 highest-use systems are excluded, each region ranged from 312,000 to 1.1 million

passenger boardings in 2022 (figure 4).

Figure 4: Passenger boardings by NPS region

Notes: N=81 systems; IR=Interior Region; NCA=National Capital Area; NPS=National Park Service

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

13

The DC Circulator, Giant Forest Shuttle, Fairfax Connections Wolf Trap Express, Hiker Shuttle (Delaware Water Gap National

Recreation Area), and Shuttle Transport (Harper’s Ferry) are the five systems that were operated by a local transit authority.

1.1

588k

984k

526k

781k

312k

356k

9.9

7.0

3.8

1.2

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

IR 6, 7 & 8 IR 1 IR 8, 9, 10 & 12 IR 1 - NCA IR 2 IR 3, 4 & 5 IR 11

Passenger Boadings (millions)

All Other Systems Top 10

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 11

Over half (59%) of passenger boardings were in systems that use shuttles, buses, vans, or trams,

and 40 were in water-based systems that use boats and ferries. Trains, trolleys, and aircraft

accounted for only less than 1% of all passenger boardings (figure 5).

Figure 5: Passenger boardings by mode

Note: N=81 systems

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

3

(11%)

1.5

(6%)

130k

(<1%)

24k

(<1%)

12.9

(48%)

9.1

(34%)

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

Shuttle/Bus/Van/Tram Ferry/Boat Train/Trolley Aircraft

Passenger Boadings (millions)

All Other Systems Top 10

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 12

Less than half of passenger boardings (42%) took place on systems operated using concession

contracts. Service contracts carried 41% of passenger boardings and 14% used cooperative

agreements. NPS-owned and operated systems carried 2% of boardings (see figure 6).

Excluding the 10 highest-use systems, concession contracts accounted for the most boardings

(7%), followed by cooperative agreements (4%), services contracts (4%) and NPS-owned and

operated (2%).

Figure 6: Passenger boardings by business model

Notes: N=81 systems; NPS=National Park Service

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

Vehicles and Vessels

Vehicle Fleets

Including operating and nonoperating systems, over half of the transit systems (52 systems, or

51.4%) were under concession contracts, of which 9 used fleets owned by the National Park

Service and 2 used fleets of mixed ownership (both NPS owned and non-NPS owned). The

National Park Service owned and operated 20 transit systems (19.8%); these tend to be small

and provided critical access, interpretive tours, or mobility to or within the park in ways not

easily provided by a private operator. Systems managed through cooperative agreements

account for 15 of the systems (14.8%). The remaining 14 transit systems (13.8%) operate under

service contracts; of these, most use vehicle fleets owned by the National Park Service, including

the large systems at Grand Canyon National Park and Zion National Parks.

2

(7%)

1.1

(4%)

1

(4%)

594k

(2%)

9.3

(35%)

2.7

(10%)

9.9

(37%)

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

Concession Contract Cooperative Agreement Service Contract NPS Owned and Operated

Passenger Boadings (millions)

All Other Systems Top 10

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 13

For the operating fleet reporting in 2022:

• NPS owned:

o 24 operating systems used National Park Service owned fleets; 12 systems with

NPS-owned fleets did not operate.

o 274 vehicles were reported to the inventory. Of those, 244 vehicles operated 30

and vehicles did not operate. Of the operating systems with NPS-owned fleets, 2

systems had a capacity for no more than 10 passengers, 11 systems had capacity

for 11–20 passengers, 10 systems had capacity for 21–40 passengers, and 5

systems had capacities over 40 passengers. Nineteen vehicles did not report

capacity.

• Non-NPS owned:

o 55 systems had non-NPS-owned and 2 mixed-ownership fleets.

o 600 vehicles were reported to the inventory. Of those, 546 vehicles operated, and

54 vehicles did not operate. Of the operating systems with non-NPS-owned or

mixed-ownership fleets, 10 systems had a capacity for no more than 10

passengers, 12 systems have capacity for 11–20 passengers, 14 systems have

capacity for 21–40 passengers, and 34 systems had capacities over 40 passengers.

Note: Some systems have varying capacity and may be counted twice.

Figure 7: Number of vehicles by fuel type

Notes: N=790 active vehicles and vessels; CNG=compressed natural gas; NPS=National Park Service

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

60

68

37

33

27

6

7

6

253

183

67

4

27

6

1

5

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

Diesel Gasoline Propane CNG Hybrid

Electric

Biodiesel Electric Other

Number of Operating Vehicles

NPS Vehicles Non-NPS Vehicles

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 14

Table 5: Number of vehicles that operated in 2022 by fuel type

Notes: N=790 active vehicles and vessels; CNG=compressed natural gas

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

Fuel Type NPS Owned

Non-NPS

Owned

Total

Diesel 60 253

313

Gasoline 68 183

251

Propane 37 67

104

CNG 33 4

37

Hybrid Electric 27 27

54

Biodiesel 6 6

12

Electric 7 1

8

Other 6 5

11

Total 244 546 790

% Alt Fuel 45% 19% 27%

Age of Vehicles

Vehicle age data was provided by 274 NPS-owned vehicles and 478 non-NPS-owned vehicles.

The age analysis excludes the 33 Red Bus Tour vehicles (Glacier National Park), which have

been retrofitted using the original 1936 exteriors and newer chassis. Given these parameters, the

age analysis includes 719 vehicles (82% of reported vehicles).

Table 6: Vehicle ownership by age c

lass

Note: N=719 vehicles and vessels

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

Vehicle Ownership

0 to 4

Years Old

5 to 9

Years Old

10 to 14

Years Old

15 Years

and Older

Total

National Park Service

19

7.9%

39

16.2%

53

22.0%

130

53.9%

241

Non-National Park

Service

63

13.2%

272

56.9%

53

11.1%

90

18.8%

478

Total

82

11.4%

311

43.3%

106

14.7%

220

30.6%

719

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 15

Figure 8: All vehicles by age class (years)

Notes: N=719 vehicles and vessels; NPS=National Park Service

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

The non-NPS fleet is decidedly newer. A larger overall proportion of newer non-NPS vehicles

suggests that older vehicles have been retired at a higher rate in recent years. The replacement of

older vehicles may reflect contract language requiring vehicles to be within a certain age range.

Seventy-six percent of the active NPS-owned fleet is 10 years or older and puts many of the

vehicles in the latter portion of their service lives. In previous years, more than 80% of the NPS

fleet was 10 years or older. While vehicle replacements have occurred, there is still a need for

vehicle replacements in the next 10 years. In addition, parks must invest in the maintenance of

older vehicles to not only keep them operating but extend their service life.

Transit vehicles operating in the parks are not used in the same way as urban transit vehicles.

Park transit vehicles are typically not used for the entire year, nor are they used as intensively as

vehicles operated in an urban environment. As a result, they may be in service for considerably

longer lifespans, and recapitalization estimates should rely on park-specific estimates that

depend on their specific use (see the “Asset Management” section and appendix F).

17

36

49

121

2

3

4

9

59

264

46

44

4

8

7

46

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

350

0 to 4 5 to 9 10 to 14 15 and greater

Number of Operating Vehicles

NPS Vehicles NPS Vessels Non-NPS Vehicles Non-NPS Vessels

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 16

Vessels

The National Park Service had 33 operating systems that use ferries or boats: 11 are for critical

access to park sites, 14 are for interpretive tours, 5 are transportation features, and 3 provide

mobility to or within the park. The National Park Service owns 18 of these vessels, and there are

96 non-NPS owned ferries or boats that operated in 2022. Vessels typically have a life cycle of

40–50 years.

Gulf Islands National Seashore purchased two ferries in 2017 using funds from the Gulf

oil spill. In 2019, 2020, and 2022, operations were impacted by several tropical storms,

hurricane, and repair efforts. In early 2022, the dock at Pensacola Beach was damaged

again, this time by a construction crane, making it unusable from April through August

2022. Only sunset cruises and minimal ferry service between Pensacola and the beach

occurred in 2022.

• Fort Matanzas National Monument replaced a boat in 2022 and plans to order a second

replacement boat in fiscal year 2023.

The Ranger III at Isle Royale National Park is over 60 years old and has outlived its

useful service life. A value analysis completed in 2019 indicates the need for a new

Ranger IV at a cost of $40–$60 million. Currently, the park began phase I to develop

detailed design and costs based on identified performance measures.

Performance Measures

The NPS Alternative Transportation Program (ATP) seeks to use meaningful, reliable data. The

objective is to use measurable, applicable, and achievable performance measures and metrics to

guide and support decision-making and management of NPS transit systems.

The performance measures below are split into the following sections that correspond to ATP

goals and the NPS National Long Range Transportation Plan:

14

visitor experience, operations,

environmental impact, and asset management. The ATP goals are included in appendix B.

Visitor Experience

This performance area addresses how park transportation systems enhance the visitor

experience. For 2022, the visitor experience performance measure includes accessibility for

mobility-impaired park visitors.

14

The long-range transportation plan can be accessed at

https://parkplanning.nps.gov/document.cfm?parkID=551&documentID=82749.

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 17

Accessibility for Visitors with Disabilities

In 2022, 59.84% of 244 operating, NPS-owned vehicles and vessels were accessible for people

with mobility impairments (figure 9). This number is a decrease of 5% from 2021; however, an

additional 21 vehicles and vessels operated in 2022. Overall, 58% of the 274 NPS-owned

vehicles and vessels are accessible.

Of the 81 operating systems with NPS-owned vehicles or vessels, 17 did not report having

vehicles or vessels that are accessible. These systems include Canal Tours (Lowell National

Historical Park), Cape Cod Coastguard Beach Shuttle (Cape Cod National Seashore), Franklin

D. Roosevelt Tram (Home of Franklin D Roosevelt National Historic Site), Full Circle Trolley

(Marsh-Billings-Rockefeller National Historical Park), Hiker Shuttle (Glacier National Park),

Green River Ferry (Mammoth Cave National Park), Historic Yellow Bus Tours (Yellowstone

National Park), Mariposa Grove Transportation Service (Yosemite National Park), MV Ranger

III (Isle Royale National Park), NPS Shuttle (Eugene O’Neil National Historic Site), Red Bus

Tours (Glacier National Park), Scranton Limited & Live Steam Excursions (Steamtown

National Historic Site), Harpers Ferry Shuttle Transport (Harpers Ferry National Historical

Park), Voyagers Boat Tour (Voyageurs National Park), Xanterra Parks and Resorts Bus Tour

(Yellowstone National Park), Snow Coaches (Yellowstone National Park), and Zion Shuttle

(Zion National Park). That number increases from 17 to 26 systems when including the systems

that did not operate in 2022: Akers Ferry (Ozark National Scenic Riverways), Cave Tours Bus

Shuttle (Mammoth Cave National Park), Fort Pickens Tram Service (Gulf Islands National

Seashore), Lakebed Tours (Johnstown Flood National Memorial), Land and Legacies Tour

(Cumberland Island National Seashore), Rapidan Camp Bus (Shenandoah National Park,

Tallgrass Bus Tours (Tall Grass Prairies National Preserve), and the Val-Kill Tram (Home of

Franklin D Roosevelt National Historic Site).

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 18

Figure 9: Accessibility of NPS-owned transit vehicles (entire fleet)

Notes: N=274 vehicles and vessels; DNO=did not operate; NPS=National Park Service

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

Operations

This section evaluates the operational performance of the NPS transit systems by measuring the

annual percent change in boardings over the last five years. In 2018, the reduced number of

boardings may be attributed to a more-intense-than-usual hurricane season and the 2018

government shutdown, along with impacts from nonreporting parks. In 2020 and 2021, the

reduced number of boardings is attributed to park closures and limited or no transit system

operations due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Year-to-Year Trends in Boardings

Figure 10 shows the percent change in boardings from 2018 to 2022. Absolute boardings dipped

slightly in 2018 due to the government shutdown and an active hurricane season that caused

many temporary park shutdowns and reached an all-time high in 2019. Due to the pandemic,

ridership declined dramatically in 2020 but has shown steady increases in 2021 and 2022, as

more systems come back online and visitors feel more comfortable riding transit. However, not

all systems have returned or are fully operational, and the assumption is some visitors are still

reluctant to get on a crowded transit vehicle. Across the nation, transit ridership rates have not

recovered to pre-pandemic levels, and post-pandemic recovery continues to be slow.

In 2022, the National Park Service received 312 million recreation visits, up 15 million visits

(5%) from 2021. While not as high as 2018 and 2019, servicewide visitation has essentially

recovered to pre-pandemic levels. Visitation in 2022 is similar to the years immediately before

the NPS centennial in 2016 and is only 6% lower than the record year (331 million visitors in

2016). Overall, 12 parks set new visitation records in 2022, none of which have transit systems.

146,

53%

98,

36%

13 DNO, 5%

17 DNO,6%

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

Accessible Not Accessible

Number of NPS Owned Transit Vehicles

Operated Did Not Operate

159, 58%

115, 42%

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 19

Figure 10: Percent change in boardings from 2018 to 2022

Source: 2018–2022 NPS transit inventory data

Table 7: Comparison of systems and boardings from 2018 to 2022

Source: 2018–2022 NPS transit inventory data

Metrics 2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Number of Systems in Inventory

(% change from previous year)

95

-4%

97

2.1%

96

-1%

97

1%

101

4.1%

Number of Systems Operating

(% change from previous year)

95

-4%

97

2.1%

66

-32%%

63

-4.5%

81

28.6%

Number of Systems New to Inventory 0 2 1 1 4

Boardings

(% change from previous year)

42,320,594

-3.2%

45,967,894

8.6%

11,098,633

-75.9%

16,300,849

46.9%

26,644,865

63.5%

42.3

46.0

11.1

16.3

26.6

-3.2%

8.6%

-76%

46.9%

63.5%

-100%

-80%

-60%

-40%

-20%

0%

20%

40%

60%

80%

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

50

2018 2019 2020 2021 2022

Percent Change

Passenger Boardings (millions)

Passenger Boardings Percent Change

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 20

Service Schedule

The 2022 inventory analyzed the reported service schedules of the 81 operating systems to

understand the general calendar spread of NPS transit systems. Although most seasonal service

dates ranged primarily over the summer and into early autumn (June to October), very few

operate in the winter (December to February), with 32% of systems (26 systems) operating year-

round (figure 11).

Peak season is defined as the period when the scheduled transit service is operating at its

greatest frequency. The most common peak season months are July and August, with shoulder

peak seasons extending May through September. For year-round systems, many parks report

peak seasons beginning as early as March and extending into September.

Systems operating year-round are among those with the highest annual ridership, representing

66% of total boardings. Of the 26 systems that operated year-round, 7 provide critical access, 10

are interpretive tours, 7 provide mobility within the park, and 2 are transportation features. The

next most common service period is 6 months out of the year (14 systems), followed by systems

that are in service for 5 months (13 systems each).

Transit systems in colder climates tend to operate for shorter seasons than those in warmer

areas. For example, systems in Interior Region 11 (Alaska) operate through September.

Conversely, many of the year-round systems are in the southern and western parts of the

country where the climates are milder. The wide range of climates encompassed by Interior

Regions 8, 9, 10, and 12—from Yosemite to Hawaii—leads to a wide range of schedules.

Figure 11: Distribution of service duration by number of months

Note: N=81 systems

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

0

1

6

8

13

14

7

3

2

0

1

26

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

Number of Systems

Number of Months in Service

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 21

Safety

The 2022 inventory included questions regarding safety at the system level. Visitor and

workforce safety are among the highest NPS priorities, and transportation is a significant source

of risk to the safety of NPS transportation system users. Collecting safety and crash information

for transit systems informs the NPS National Long Range Transportation Plan’s transportation

safety goals and performance metrics.

In 2022, the number of NPS transit systems that reported traffic accidents increased from three

parks (13 accidents) to six parks (14 accidents). The number of affected systems doubled from

2021, while the number of accidents remained stable since doubling from 2020 to 2021. Of the

accidents reported in 2022, two had passengers on board during the accident (table 8),

compared to one in 2021. Similar to 2021, none of these accidents resulted in an injury or

fatality, although one did involve a bicyclist. Five systems reported minor vehicle damage, and

two systems had multiple accidents with varying level of damage. At least two systems reported

accidents due to driver error and two systems reported an accident due to the error of others.

Harpers Ferry Shuttle Transport: A bus hit a sign at the visitor center bus loop. The

bus was out of service for two weeks.

Franklin D. Roosevelt Tram Tour: The tram was damaged on the passenger side when

the employee driving the tram mistakenly struck the side of a building to avoid an

obstruction, causing damage to both the tram and the building. No one was injured.

South Rim Shuttle Service: The shuttles experienced eight incidents during the year;

four occurred on route. None of the accidents were the error of the shuttle driver, and

there were no injuries reported in any of the accidents. Some minor costs for repairs to

buses were needed.

Voyager Boat Tour: Two incidents occurred with two of the vessels, putting them out

of service, one for two days and one for one week. Both accidents were caused by ships

striking rocks on route; no passenger injuries were reported.

Yosemite Valley Shuttle: The system reported two minor accidents. The first incident

involved a visitor's private vehicle, and the other contact with a metal-framed sign.

Zion Shuttle: A minor incident involved an inexperience cyclist using an e-bike who

crossed yellow line, colliding with front corner of bus trailer.

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 22

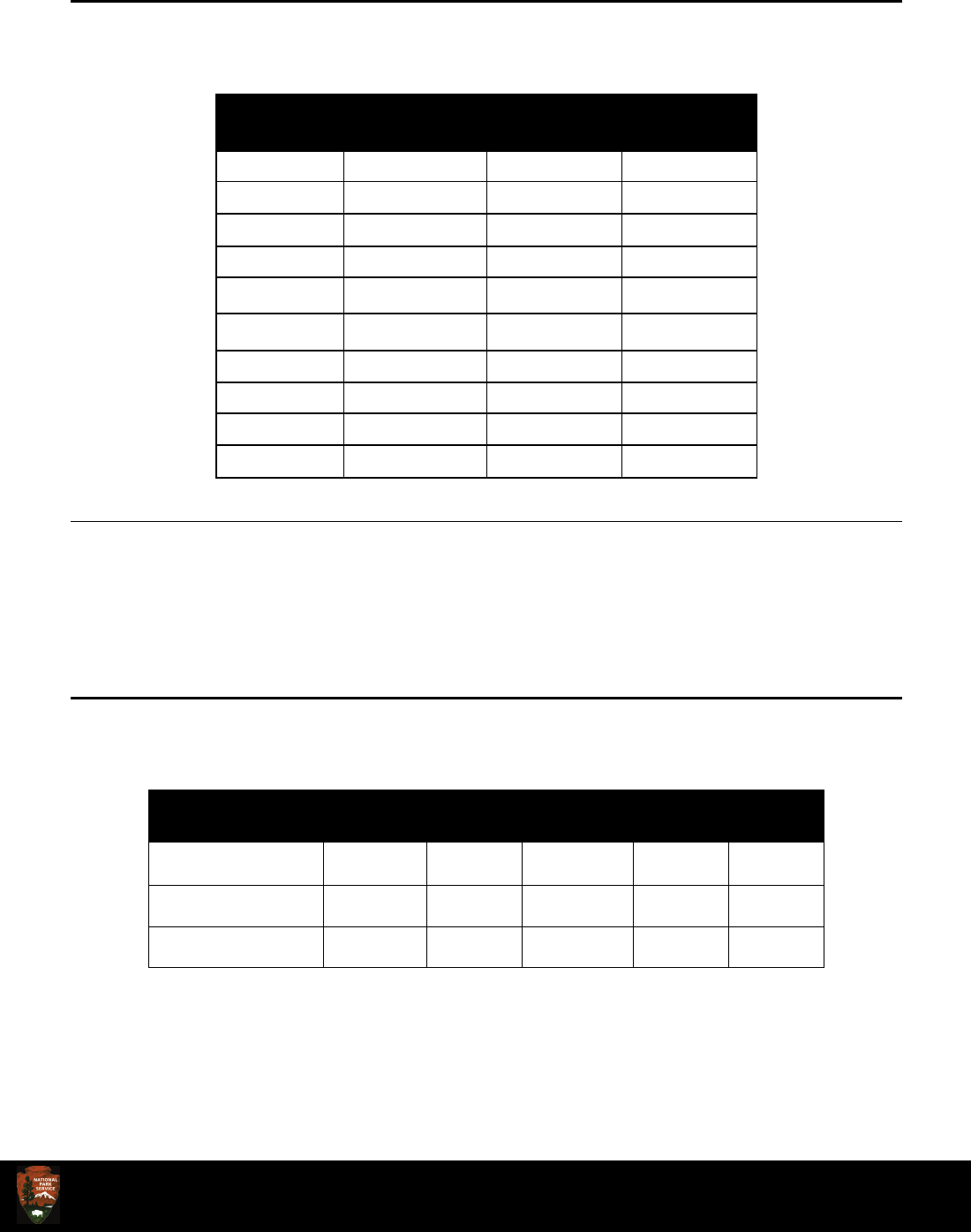

Table 8: Response to safety and operational questions

Note: HAFE=Harpers Ferry; HOFR=Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt National Historic Site; GRAC=Grand Canyon National Park;

VOYA=Voyageurs National Park; YOSE=Yosemite National Park; ZION=Zion National Park

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

Park

System

Name

Number

of

Accidents

Passengers

on Board

Injuries

or

Fatalities

Bicycles or

Pedestrians

Accident

Occurred

on Route

Result of

Driver

Error

Real

Property

Damaged

HAFE

Harpers Ferry

Shuttle

Transport

1 No No No Yes Yes Yes

HOFR

FDR Tram

Tour

1 No No No No No Yes

GRCA

South Rim

Shuttle

Service

8 Yes No No Yes No Yes

VOYA

Voyager Tour

Boat

2 Yes No No Yes No Yes

YOSE

Yosemite

Valley Shuttle

2 No No No No Yes Yes

ZION Zion Shuttle 1 No No Yes No No No

F

igure 12: Year-to-year comparison of reported accidents

Source: 2019–2022 NPS transit inventory data

5

3 3

6

7

5

13

14

71%

260%

108%

0%

50%

100%

150%

200%

250%

300%

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

2019 2020 2021 2022

Number of Systems Reporting Accidents Number of Reported Accidents Change in Reported Accidents

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 23

Environmental Impact

Since 2017, the transit inventory uses the US Environmental Protection Agency's Motor Vehicle

Emissions Simulator (MOVES) for estimating NPS transit vehicle emissions.

15

The Motor

Vehicle Emissions Simulator is a state-of-the-science emissions modeling software that uses

preloaded measurement data to estimate emissions rates for different vehicle types, model years,

fuel types, and road types across several Clean Air Act criteria pollutants “from the bottom-up”

for both on- and off-road vehicles, including waterborne vessels. MOVES software is also the

regulatory standard for emissions inventory analyses under the Clean Air Act and related

legislation.

16

MOVES software bases emissions estimates on observations of actual vehicle

operations.

This section describes the results of the 2022 emissions analysis with respect to carbon dioxide

(CO

2

). The results for the other criteria pollutants—nitrogen oxides, volatile organic compound,

and particulate matter—as well as a detailed description of the analysis methodology, are

presented in appendix E.

The COVID-19 pandemic had a significant impact on passenger vehicle miles traveled and

transit system operation in parks in 2020 and 2021. However, transit system activity started to

rebound in 2022. Vehicle miles traveled across all regions increased 385% from 2021 and 601%

from 2020 levels. The increased emissions level is directly related to the number of operational

systems and increased operations of systems nationwide.

Table 9: Comparison of emission results

Source: 2020–2022 NPS transit inventory data

Metrics 2020 2021 2022

Change 2022

vs. 2021

(percent)

Change 2022

vs. 2020

(percent)

Number of Operating

Systems

66 63 81 29% 23%

Count of Vehicles 913 803 817 2% -11%

Miles Traveled 3,408,710 4,925,288 19,953,523 305% 485%

Ferry Hours 19,735 38,409 43,857 14% 122%

Carbon Dioxide Emissions 12,873.50 22,491 54,291.98 141% 322%

15

This national transit inventory uses version MOVES 3.0.3, which was released in January 2022.

16

“Official Release of the MOVES2014 Motor Vehicle Emissions Model for SIPs and Transportation Conformity.” Federal Register

79:194 (October 7, 2014), p. 60343. Available from the Government Publishing Office at: https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-2014-

10-07/pdf/2014-23258.pdf.

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 24

Annual CO

2

Emissions

Figure 13 shows the results of MOVES carbon dioxide emissions modeling for transit systems,

aggregated to the regional level and split by ownership. Across all regions, NPS-owned transit

fleets emitted just over 24,163 metric tons of CO

2

in 2022. Interior Regions 8, 9, 10 and 12

experienced the highest number of ferry miles, resulting in the highest non-NPS-owned vehicles

CO

2

emissions. Interior Regions 6, 7, and 8 have the overall highest amount of vehicle miles

traveled, which results in the highest CO

2

emissions.

Table 10: Distribution of miles and CO

2

emissions by vehicle ownership

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

Ownership

Vehicles

(number)

Vehicles

(percent)

Miles

Traveled

Miles

(percent)

CO

2

(metric tons)

CO

2

(percent)

NPS Owned 274 35% 3,771,613 19% 24,163.30 44%

Non-NPS Owned 546 65% 16,181,910 81% 17,924.57 56%

Total 820 100% 19,953,523 100% 42,087.87 100%

F

igure 13: Annual CO

2

emissions

Notes: IR=Interior Region; NCA=National Capital Area; NPS=National Park Service

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

89

20,505

1,743

1,731

95

16,648

882

3,667

476

2,267

2,615

3,575

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

IR 8, 9, 10, 12 IR 6, 7, 8 IR 3, 4, 5 IR 1 IR 1 - NCA IR 2 - SAG IR 11

Emissions (tons)

NPS Vehicles Non-NPS Vehicles

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 25

Diverted Passenger Vehicle Trips and CO

2

Emissions Avoided

The benefits of using transit include:

reduction of the number of vehicle trips in parks,

congestion relief on park roads by carrying more people per square foot of road space,

elimination of associated fuel-inefficient driving behaviors like extended idling and

stop-and-go,

potential to influence how visitors spend their time in the park, and

removal of long lines of cars from viewsheds.

Servicewide, an estimated 10.2 million private vehicle trips were eliminated in 2022, double the

diverted passenger vehicle trips estimated in 2021, and a reduction of nearly 231,655 metric tons

of CO

2

emissions; without transit service, there would have been an additional 618 million miles

driven in private vehicles. As stated previously, regions with high transit use and more boardings

divert more personal vehicles from the road.

Asset Management

Performance measurement for assets helps support the long-term financial viability of the

transit systems through tracking the age of NPS-owned vehicle fleets and estimating fleet

recapitalization costs. In this context, “vehicles” refers only to on-road motorized vehicles and

excludes nonroad transportation, such as ferries, locomotives, snow coaches, and aircraft. Any

of those described in table 9 are shown only for reference and were not analyzed for

recapitalization estimates.

Average Age of NPS Vehicles

Table 11 reports the aggregate average age for NPS-owned transit vehicles servicewide and

includes all NPS-owned vehicles regardless of whether they operated or not in 2022. The

average age of each NPS vehicle type is below the service life for most vehicle types, but many

categories include vehicles older than their typical lifespan. In the case of medium-duty transit,

the average age is the anticipated service life. Notably, 65 vehicles will exceed their service life in

next five years; of these, 50 are heavy-duty transit or medium-duty shuttles. On average, heavy-

and medium-duty shuttle buses are the newest vehicles in the NPS-owned fleet, which is

reflective of the fleet replacements occurring at Glacier, Grand Canyon, Yosemite, and Zion

National Parks.

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 26

Table 11: Vehicle age for NPS transit vehicle types

17

Notes: N=241 vehicles and vessels;

18

N/A=not applicable

Source: 2022 NPS transit inventory data

Vehicle Type

Average

Age

Number of

Vehicles

Service

Life

(years)

Number of

Vehicles Beyond

Service Life*

Number of Vehicles

Exceeding Service Life

in Next 10 Years*

Tram/Golfcart 6 12 11 2 10

Passenger Van 14 21 10 18 3

Light-Duty Shuttle 12 20 15 5 14

Medium-Duty

Shuttle

12 41 15 16 23

Medium-Duty

Transit

19 34 18 24 8

Heavy-Duty

Transit

13 68 18 23 30

Ferry/Boat 26 18 N/A N/A 0

Train/Streetcar 55 5 N/A N/A 0

School Bus 17 7 18 1 6

Snowmobile/Snow

Coach

54 12 N/A N/A 0

Van 9 3 10 3 0

Total – 241 – 92 94

*Number of vehicles beyond service life in the next 10 years is a total of 186 vehicles. This includes 92 vehicles that are operating

beyond their estimated service life in 2022 and 94 vehicles exceeding service life in the next 1–10 years (2023–2032). These columns are

calculated using the vehicle’s age and estimated service life.

Transition to Electric Vehicles and Estimated Vehicle Recapitalization Needs

Executive Order 14008, “Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad,” requires federal

agencies to establish a plan that will enable government motor vehicle fleets to transition to

clean and-zero emission vehicles. Additionally, Executive Order 14057, “Catalyzing Clean

Energy Industries and Jobs Through Federal Sustainability,” establishes a goal of 100% zero-

emission light-duty vehicle acquisitions by 2027 and 100% zero-emission vehicle acquisitions by

2035.

The transition to electric vehicles will occur when a vehicle needs to be replaced. Estimates of

NPS-owned vehicle replacement needs begin with vehicle ages, along with the associated

replacement costs and service life assumptions shown in appendix F. Each park is responsible

for determining when a vehicle needs to be replaced, which is dependent on funding availability

and other factors. Service life is highly dependent on vehicle use, in addition to vehicle age;

17

The 2020 recategorization of the NPS fleet vehicles resulted in new categories and shifting vehicles to more appropriate vehicle

type categories compared to past inventories. See appendix F for more information.

18

The Glacier National Park Red Bus Tours vehicles were excluded from this analysis, as they have been extensively retrofitted

during their 80-plus years in service.

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 27

therefore, more detailed information is needed before determining if a vehicle is truly due for

replacement.

Based on an analysis using the methodology outlined in appendix F, the National Park Service is

facing a large fleet replacement need of 228 vehicles over the next 10 years and an estimated

$187 million in NPS-owned transit vehicle capital costs.

19

These fleet replacements include

legacy transit systems at Acadia, Yosemite, and Grand Canyon National Parks. The 10-year

estimated cost does not include the ongoing fleet replacement at Zion National Park or electric

vehicle service equipment and other infrastructure upgrades to accommodate transitioning to

electric vehicles. Projected costs and escalation are calculated based on 2022 dollars and may

vary from year to year as vehicles from different systems are replaced or rehabilitated to extend

their service life.

Next Steps

The inventory continues to provide essential information on NPS transit systems at the park,

regional, and national levels. This effort allows stakeholders to understand the basic

characteristics of NPS transit systems, including how many visitors are served, the number and

types of transit systems, vehicle service life and fuel types, the business models under which

these systems operate, and performance measures (including emissions).

The transit inventory collects annual operational information to supplement other data

initiatives that focus on NPS fixed real property assets. This effort provides a consistent

platform to efficiently gather information that can be compared through time and enables the

National Park Service to examine disparate transit systems as a whole and evaluate their benefits

and impacts. As visitation at national parks increases, transit systems remain important assets for

reducing resource impacts from personal vehicles while improving access and enhancing the

visitor experience.

The following lessons will be incorporated to improve future transit data calls:

Continued Coordination with Relevant NPS Stakeholders: Continue sharing data

and identifying ways the transit data can be used to support program missions, goals, and

outcomes across the National Park Service. Consider stronger coordination with

concessions and service contracts to include data requirements in new contracts.

Create New and/or Refine Existing Data Elements: Continue to refine the number of

fields in the data call, adding or removing data fields as necessary to gather only

necessary information while limiting the burden of data collection on the park staff.

Improve the Data Collection Online Tool: The online data collection tool moved to

the Microsoft PowerApps platform in 2019. A limitation of this tool is that it is restricted

19

The estimated vehicle replacement costs assume an eligible Green Fleet vehicle base model cost. Often, purchase price exceeds the

base model cost because of selected vehicle options. In addition, costs do not include electric vehicle charging equipment and

associated infrastructure needs.

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 28

to NPS users only, and concessioners are not able to access the tool. The option for

concessioners to submit their data via spreadsheet was provided again for 2022. The

interactive web report was also updated for 2022, and the online report includes all

historic NTI data. The National Park Service anticipates updating the data collection

tool and data storage for performance enhancements for the 2023 data collection.

Continue to Expand Performance Measures Analysis: Continue including additional

performance measures to track progress of NPS transit systems over time and include in

this report. Collaborate with other NPS planning efforts to provide measurable data.

Shift safety questions to a quantitative input and collaborate with the transportation

safety program manager for reporting.

Communicate the Benefit and Impact of NPS Transit Systems to Visitors: Consider

communicating to visitors how their choice to use transit has a positive impact on park

resources through reducing congestion and emissions from private vehicles. The positive

impacts of transit use could be communicated in a variety of ways, such as consistent

signage throughout the national park system, through social media, or on the NPS

website.

Consider Multimodal Connections to Transit: The transit inventory could be

expanded to include connections to transportation trails.

20

Considering opportunities

for bicycling and walking in national parks and connections to transit could give a better

picture of the opportunities for exploring national parks without using a private vehicle.

Coordinate with the Vehicle Health Index to Refine Recapitalization Analysis and

Anticipated Service Life: Developed from industry standard approaches to fleet

condition assessment, the Vehicle Health Index (VHI) provides a data-driven approach

to understanding fleet condition across the National Park Service’s portfolio of fleet

assets. The Vehicle Health Index consists of a series of rapid-visual and diagnostic tests,

scored 0–10, for each subcomponent of a vehicle (e.g., engine, drivetrain, interior) to

generate a “Total Vehicle Score,” the official VHI metric. Data collected from VHI

assessments will enhance existing asset management practices by providing consistent,

point-in-time assessments of fleet condition. The assessment will inform both the

expected service life for vehicles on public lands and the recapitalization analysis.

20

NPS definition of a “transportation trail”: Multimodal trail that accommodates pedestrians and/or bicycles and connects to a

larger transportation system, including land- and water-based transit and/or regional trail systems or direct connections to a

community (not solely recreational trails).

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 29

Explore Count Methodology Standardization: Eighty-five percent of boardings are

attributed to 10 systems. Understand the count methodology for these 10 systems and

develop standardization in count methodology. Consider developing standard operating

procedures/business practices for the remaining types of count methodologies or

consider automating manual counts, where appropriate.

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 30

Appendixes

Appendix A – Acknowledgments

The National Park Service would like to thank the numerous NPS transit system contacts who

graciously provided their time, knowledge, and guidance in the development of this inventory

and new web application.

Special thanks to each park and park contact who provided data for the 2021 inventory year. A

list of each park contact is included in appendix D.

Interior Region 1 – National

Capital Area

Ryan Yowell

National Capital Region

Interior Region 1

Amanda Jones

Northeast Region

Interior Region 2 – South Atlantic

Group

Lee Edwards

Southeast Region

Interior Region 3, 4, and 5

Mark Mitts

Midwest Region

Interior Regions 6, 7, and 8

Michael Madej

Regional Office

Interior Regions 8, 9, 10, and 12

Erica Simmons

Regional Office

Interior Region 11

Kevin Doniere

Alaska Region

Washington Support Office

Steve Suder

Alternative Transportation Program

J

oni Gallegos

Alternative Transportation Program

Jennifer Miller

Program Analyst

Denver Service Center

Cliff Burton

Information Management

Robert Maupin

Transportation Division

C

hantae Moore

Transportation Division

B

riAnna Weldon

Transportation Division

Volpe Center

(Department of Transportation)

Amalia Holub

Public Lands Team

Anjuliee Mittelman

Environmental Measurement and Modeling

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 31

Appendix B – National Park Service Alternative Transportation Program

Goals and Objectives

GOAL: Cultivate improvements in transportation connectivity, convenience, and safety

for visitors and workforce.

OUTCOME: Access to, from, and within national parks is convenient, safe, and well-

connected via appropriate and integrated transportation solutions.

Develop transportation options that meet the diverse needs of park visitors and

NPS workforce.

Connect and enhance existing transportation options.

Minimize injuries, fatalities, and crashes associated with all modes of

transportation.

Participate in local, regional, and statewide transportation planning processes to

ensure appropriate integration of NPS transportation infrastructure, systems, and

services.

GOAL: Provide quality transportation experiences that enhance park visits.

OUTCOME: NPS transportation systems contribute to the positive experience of park

visitors.

Improve visitor access to appropriate destinations.

Use transportation to educate and inform visitors about park resources and

services.

Reduce disruptions to the visitor experience related to vehicle traffic congestion.

Design and adapt transportation systems to complement each park’s unique

context and mission.

GOAL: Demonstrate leadership in environmentally responsible transportation.

OUTCOME: The National Park Service is recognized as a leader in environmentally

responsible transportation.

Prioritize investments and operations that reduce vehicle emissions, noise and

light pollution, traffic congestion, and unendorsed parking.

Educate park visitors and workforce about the environmental benefits of

transportation options within and beyond park boundaries.

Contribute to NPS and park greenhouse gas emissions reduction goals.

NPS National Transit Inventory and Performance Report, 2022 32

Implement proven green transportation innovations and best practices, where

appropriate.

GOAL: Ensure the long-term financial viability of NPS transportation infrastructure,

systems, and services.

OUTCOME: Funding is adequate to maintain transportation infrastructure, operate

transportation systems, and manage transportation services now and into the foreseeable

future.

Consider the full range of business models and associated lifecycle costs (direct

and indirect) before making investments.

Increase the flexibility of funding mechanisms to better support transportation

options.