Local Mitigation

Planning Handbook

May 2023

Local Mitigation Planning Handbook

This page intentionally left blank

Local Handbook Update

i

Table of Contents

Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 1

Handbook Format and Organization ................................................................................................. 2

Mitigation and the Emergency Management Cycle .......................................................................... 3

Mitigation Builds Climate Resilience ................................................................................................ 4

Mitigation Planning is Risk-Informed Decision Making .................................................................... 6

Planning is the Foundation for Mitigation Investments ................................................................... 6

Guiding Principles .............................................................................................................................. 7

Task 1. Determine the Planning Area, Process and Resources ........................................ 8

1.1. Initial Considerations ................................................................................................................. 8

1.1.1. New Plan or Plan Update ................................................................................................ 8

1.1.2. Confirm Participant(s) and Planning Area ..................................................................... 8

1.1.3. Review Previous Plan and Scope Update ................................................................... 11

1.2. Right-Sizing the Scope of the Planning Process .................................................................... 11

1.2.1. Preliminary Questions .................................................................................................. 11

1.2.2. Schedule Considerations ............................................................................................. 12

1.3. Organizing Resources ............................................................................................................. 13

1.3.1. People and Partnerships.............................................................................................. 13

1.3.2. Plans, Studies and Data .............................................................................................. 15

1.3.3. Technical Assistance .................................................................................................... 17

Task 2. Build the Planning Team ..................................................................................... 19

2.1. Building the Planning Team .................................................................................................... 19

2.1.1. Multi-Jurisdictional Planning Team ............................................................................. 19

2.1.2. Identify Planning Team Members ............................................................................... 21

2.1.3. Promote Participation and Buy-In ................................................................................ 28

2.1.4. Engage Local Leadership ............................................................................................. 31

Task 3. Create an Outreach Strategy ............................................................................... 33

3.1. Plan for Public Involvement .................................................................................................... 34

Local Handbook Update

ii

3.2. Create an Equitable Planning Process ................................................................................... 35

3.3. Community Rating System ..................................................................................................... 38

3.4. Develop the Outreach Strategy .............................................................................................. 38

3.5. Plan Ahead for Engaging Meetings ........................................................................................ 43

3.6. Coordinate Multi-Jurisdictional Outreach ............................................................................... 45

3.7. Bringing It All Together: Describe the Planning Process ........................................................ 46

Task 4. Conduct a Risk Assessment ................................................................................ 48

4.1. Defining Risk Assessment ...................................................................................................... 48

4.2. Steps to Conduct a Risk Assessment ..................................................................................... 50

4.2.1. Identify Hazards ............................................................................................................ 51

4.2.2. Describe Hazards ......................................................................................................... 52

4.2.3. Identify Assets .............................................................................................................. 60

4.2.4. Analyze Impacts ............................................................................................................ 68

4.2.5. Summarize Vulnerability .............................................................................................. 77

4.3. Document the Risk Assessment ............................................................................................ 78

Task 5. Review Community Capabilities .......................................................................... 79

5.1. Capability Assessment ............................................................................................................ 79

5.2. Types of Capabilities ............................................................................................................... 80

5.2.1. Planning and Regulatory .............................................................................................. 81

5.2.2. Administrative and Technical ...................................................................................... 83

5.2.3. Financial ........................................................................................................................ 84

5.2.4. Education and Outreach .............................................................................................. 85

5.3. National Flood Insurance Program ......................................................................................... 87

5.3.1. NFIP Participation ......................................................................................................... 88

5.3.2. Adoption of NFIP Standards and Maps ....................................................................... 89

5.3.3. Staffing, Enforcement and Continued Compliance in the NFIP ................................ 90

5.3.4. Substantial Damage and Substantial Improvement .................................................. 92

5.4. Documenting Capabilities ....................................................................................................... 92

Task 6. Develop a Mitigation Strategy ............................................................................. 93

Local Handbook Update

iii

6.1. The Mitigation Strategy: Goals, Actions and Action Plan ....................................................... 93

6.2. Mitigation Goals ...................................................................................................................... 94

6.3. Mitigation Actions ................................................................................................................... 96

6.3.1. Types of Mitigation Actions .......................................................................................... 97

6.3.2. Identifying Mitigation Actions .................................................................................... 100

6.4. Prioritize Mitigation Actions .................................................................................................. 106

6.4.1. Cost-Benefit Review ................................................................................................... 106

6.4.2. Criteria for Analysis .................................................................................................... 106

6.4.3. Action Prioritization .................................................................................................... 108

6.5. Create an Action Plan for Implementation ........................................................................... 109

6.5.1. Integrate Into Existing Plans and Procedures .......................................................... 109

6.6. Implement Mitigation Actions ............................................................................................... 111

6.6.1. Assign a Responsible Agency .................................................................................... 112

6.6.2. Identify Potential Resources ...................................................................................... 112

6.6.3. Estimate the Timeframe ............................................................................................ 112

6.6.4. Communicate the Mitigation Action Plan ................................................................. 114

6.7. Update the Mitigation Strategy ............................................................................................. 114

6.7.1. Describe Changes in Priorities .................................................................................. 115

6.7.2. Evaluate Progress in Implementation ....................................................................... 116

Task 7. Keeping the Plan Current .................................................................................. 118

7.1. Plan Maintenance Overview ................................................................................................. 118

7.2. Monitoring ............................................................................................................................. 119

7.2.1. Evaluating ................................................................................................................... 120

7.2.2. Updating ...................................................................................................................... 122

7.3. Continue Public Involvement ................................................................................................ 124

Task 8. Review and Adopt the Plan ................................................................................ 127

8.1. Review of the Plan ................................................................................................................ 127

8.1.1. Local Plan Review ...................................................................................................... 127

8.1.2. State Review ............................................................................................................... 128

Local Handbook Update

iv

8.1.3. FEMA Plan Review ...................................................................................................... 128

8.2. Plan Adoption ........................................................................................................................ 128

8.2.1. Multi-Jurisdictional Adoption Considerations ........................................................... 129

8.2.2. All Adoption Resolutions Submitted with Plan ......................................................... 130

8.2.3. Approvable Pending Adoption ................................................................................... 130

8.3. Plan Approval ........................................................................................................................ 132

8.4. Additional Considerations ..................................................................................................... 134

8.5. Celebrate Success ................................................................................................................ 134

Task 9. Create a Safe and Resilient Community ........................................................... 136

9.1. What Is Resilience? .............................................................................................................. 136

9.2. Role of Local Officials in Resilience ..................................................................................... 136

9.2.1. Leveraging Your Partnerships .................................................................................... 137

9.2.2. Involve the Whole Community ................................................................................... 138

9.2.3. Plan Holistically .......................................................................................................... 139

9.3. Assess Your Capacity ............................................................................................................ 141

9.4. Prepare for Future Opportunities ......................................................................................... 141

9.5. What Does Implementation Look Like? ............................................................................... 142

9.5.1. Identify Projects .......................................................................................................... 142

9.5.2. Develop and Leverage Momentum ........................................................................... 142

Annex A. Resources for Resilience ......................................................................................... 144

1. Local Resources ................................................................................................................... 144

2. State Resources ................................................................................................................... 144

3. Federal Resources ............................................................................................................... 144

3.1. FEMA Mitigation Grant Programs .............................................................................. 144

3.2. Technical Assistance .................................................................................................. 146

4. Best Practices ...................................................................................................................... 147

Annex B. Worksheets, Samples and Starter Kits ................................................................... 148

Background ................................................................................................................................... 149

Planning Process .......................................................................................................................... 149

Local Handbook Update

v

Worksheet 1: Identifying and Engaging the Planning Team ................................................. 149

Sample Planning Process Schedule ....................................................................................... 152

Sample Voluntary Participation Agreement ........................................................................... 153

Sample Public Opinion Survey ................................................................................................ 156

Sample Plan Organization ...................................................................................................... 163

Considering a Consultant to Support Local Mitigation Planning Starter Kit ........................ 169

Local Hazard Mitigation Plan Press Release Starter Kit ....................................................... 177

Local Hazard Mitigation Plan and Community Rating System Crosswalk Starter Kit ......... 181

Risk Assessment .......................................................................................................................... 190

Worksheet 2: Hazard Identification ........................................................................................ 190

Worksheet 3: Identifying Vulnerable Assets .......................................................................... 192

Risk Assessment Starter Kit ................................................................................................... 195

Mitigation Strategy ....................................................................................................................... 205

Worksheet 4: Capability Assessment ..................................................................................... 205

Worksheet 5: National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) ...................................................... 210

Worksheet 6: Hazard Information Integration ....................................................................... 213

Worksheet 7: Mitigation Action Selection .............................................................................. 220

Worksheet 8: Mitigation Action Implementation ................................................................... 223

Keeping the Plan Current ............................................................................................................. 225

Worksheet 9: Action Monitoring Form ................................................................................... 225

Worksheet 10: Plan Update Evaluation Form ....................................................................... 227

Plan Adoption ................................................................................................................................ 230

Sample Adoption Resolution .................................................................................................. 230

Annex C. Local Mitigation Plan Review Tool ........................................................................... 231

Cover Page .................................................................................................................................... 231

Multi-Jurisdictional Summary Sheet ............................................................................................ 233

Plan Review Checklist .................................................................................................................. 234

Element A: Planning Process .................................................................................................. 234

Element B: Risk Assessment .................................................................................................. 235

Element C: Mitigation Strategy ............................................................................................... 237

Local Handbook Update

vi

Element D: Plan Maintenance ................................................................................................ 238

Element E: Plan Update .......................................................................................................... 239

Element F: Plan Adoption ........................................................................................................ 240

Element G: High Hazard Potential Dams (Optional) .............................................................. 241

Element H: Additional State Requirements (Optional) .......................................................... 242

Plan Assessment .......................................................................................................................... 243

Element A. Planning Process .................................................................................................. 243

Element B. Risk Assessment .................................................................................................. 243

Element C. Mitigation Strategy ............................................................................................... 243

Element D. Plan Maintenance ................................................................................................ 243

Element E. Plan Update .......................................................................................................... 243

Element G. HHPD Requirements (Optional) .......................................................................... 243

Element H. Additional State Requirements (Optional) .......................................................... 244

Local Handbook Update

1

Introduction

Mitigation planning provides a framework local governments can build on to lessen the impacts of

natural disasters. By encouraging whole-community involvement, assessing risk and using a range of

resources, local governments can reduce risk to people, economies and natural environments. This

Local Mitigation Planning Handbook (Handbook) guides local governments, including special

districts, as they develop or update a hazard mitigation plan. The Handbook will:

Help local governments meet the requirements in the Local Mitigation Planning Policy Guide

(the

Guide) and Title 44 of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) for FEMA approval. An approved,

adopted mitigation plan is a gateway to apply for FEMA Hazard Mitigation Assistance (HMA) and

High Hazard Potential Dam (HHPD) grant programs.

Provide useful ideas and approaches that aid communities in reducing vulnerabilities and long-

term risk from natural hazards and disasters through planning.

The Handbook is a companion to the Guide. The Guide helps local governments understand the

requirements in the CFR. It also assists state and federal officials who provide training and technical

assistance to local governments during their review and approval of local plans. The Handbook, on

the other hand, gives advice and approaches for developing these plans.

Key Terms

Hazard Mitigation is any sustained action taken to reduce or eliminate long-term risk to life and

property from hazards.

Mitigation Planning is a community-driven process to help state, local, tribal and territorial

(SLTT) governments plan for hazard risk. By planning for risk and setting a strategy for action,

governments can reduce the negative impacts of future disasters.

Community Resilience is a community’s ability to prepare for anticipated hazards, adapt to

changing conditions, and withstand and recover rapidly from disruptions. Activities such as

disaster preparedness (which includes prevention, protection, mitigation, response and

recovery) and reducing community stressors (the underlying social, economic and

environmental conditions that can weaken a community) are key steps to resilience.

Community Lifelines are the most fundamental services in the community that, when

stabilized, enable all other aspects of society to function. The integrated network of assets,

services and capabilities that make up community lifelines are used day to day to support

recurring needs. Lifelines enable the continuous operation of critical government and business

functions and are essential to human health and safety or economic security, as described in

the National Response Framework, 4th Edition (October 28, 2019).

Local Handbook Update

2

Handbook Format and Organization

The mitigation planning process is slightly different for each SLTT government. However, no matter

the plan type, there are four core steps in completing a hazard mitigation plan or plan update. Within

each step there are tasks which, taken together, help to build a hazard mitigation plan.

This handbook is organized around the four steps and nine recommended tasks for developing a

local hazard mitigation plan (Figure 1). Some tasks can be completed at the same time. Others

depend on completing earlier tasks. Tasks 1 through 3 set up the process and people needed to

complete the remaining tasks. They also advise on the best ways to document the planning process.

Tasks 4 through 8 explain the specific analyses and decisions that need to be completed and

recorded in the plan. Task 9 provides resources for carrying out your plan.

Figure 1: Local Mitigation Planning - Steps and Tasks.

In addition to its narrative, this Handbook uses three kinds of callout boxes to explain core concepts,

provide examples, and share resources.

Blue Callout Boxes: Context and Extra Help

Blue callout boxes provide extra information that augments the narrative of each task. These

boxes include tips and tricks, spotlights and insights for the reader.

Local Handbook Update

3

Green Callout Boxes: Policy Connections

Green callout boxes highlight connections between the Handbook and the Guide. Each green

box appears at the end of a section related to a specific element of the Guide. For example,

Task 3, Create an Outreach Strategy, helps a plan meet Element A1 in the Guide.

Gray boxes: Case Studies

Grey callout boxes present case studies. These case studies provide examples of how an idea

or component has been carried out in the real world by local communities.

The Handbook also includes the following annexes:

Annex A: Resources for Resilience

Annex B: Worksheets, Samples and Starter Kits

Annex C: Local Mitigation Plan Review Tool

Mitigation and the Emergency Management Cycle

Hazard mitigation is the cornerstone of emergency management. It is the ongoing effort to lessen the

impact that disasters can have on people and property. Without mitigation, the same people,

property and community lifelines are affected over and over again.

The emergency management cycle generally has four phases:

Preparedness is when we develop or update activities, programs and systems before an event

happens. These activities are often tested (or exercised) in non-emergency situations. This tests

their effectiveness. Emergency managers also assess potential risks, hazards and vulnerabilities

in this phase.

Response focuses on the immediate and short-term effects of a disaster. It is usually focused on

life safety and preventing immediate damage.

Recovery is a long-term phase that looks to return a community to normal, or to a more resilient

state, after a disaster.

Mitigation focuses on building (or rebuilding) in ways that reduce the risk more permanently. It is

an activity that can occur at any point in the emergency management cycle. For example,

communities can undertake mitigation actions before a disaster (the preparedness phase) or

while rebuilding after a disaster (the recovery phase).

Local Handbook Update

4

Figure 2: The emergency management cycle.

A core responsibility of local governments is to protect health, safety and public welfare. Investing in

mitigation supports this responsibility. According to the National Institute of Building Sciences’

Natural Hazard Mitigation Saves 2019 report, every $1 in federal grants invested in mitigation can

save up to $6. Mitigation can:

Protect public safety and prevent loss of life and injury.

Build resilience to current and future disaster risks.

Prevent damage to a community’s economic, cultural and environmental assets.

Reduce operational downtime and speed up the recovery of government and business after

disasters.

Reduce the costs of disaster response and recovery, as well as the exposure to risk for first

responders.

Help achieve other community goals, such as protecting infrastructure, preserving open space

and boosting economic resilience.

Mitigation Builds Climate Resilience

Disasters can cause loss of life, damage buildings and infrastructure, and have devastating effects

on a community’s economic, social and environmental well-being. Climate change is increasing the

number and intensity of disasters overall and, in many communities, is changing the landscape of

risk. These trends make mitigation even more important. By taking future climate change into

account and proactively reducing risk, communities increase their chance of withstanding future

events.

Local Handbook Update

5

Natural and climate disaster risk information that is accurate, comprehensive, and produced or

endorsed by an authoritative source can help decision makers better assess their community’s risk.

Across the United States, communities are working to build resilience to hazards such as extreme

heat, drought, flooding and wildfires. Adaptation to climate change also creates resilience.

The mitigation plan provides a ready-made opportunity for communities to account for climate

change and climate risks in their planning. The plan’s risk assessment must include the probability

of future hazard events. At its most basic, probability is the likelihood of a hazard happening. The

probability description must discuss any hazard characteristics that may change, such as location,

extent, duration and/or frequency. The mitigation strategy is a chance to identify, evaluate and carry

out actions that will reduce future climate change-related risks. The mitigation plan also can and

should be integrated with other community climate resilience activities, like a climate adaptation

plan or a greenhouse gas reduction strategy.

Climate Change Terminology

Climate is the usual weather of a place. Climate can be different for different seasons. A place

might be mostly warm and dry in the summer but be cool and wet in the winter.

Climate Change refers to “changes in average weather conditions that persist over multiple

decades or longer. Climate change encompasses both increases and decreases in

temperature, as well as shifts in precipitation, changing risk of certain types of severe weather

events, and changes to other features of the climate system.”

Climate Adaptation refers to adapting to life in a changing climate. It involves adjusting to

actual or expected future climate. The goal is to reduce risks from the harmful effects of

climate change (like sea-level rise, more intense extreme weather events, or food insecurity). It

also includes making the most of any potential beneficial opportunities associated with climate

change (for example, longer growing seasons or increased crop yields in some regions).

Climate Mitigation involves reducing the flow of heat-trapping greenhouse gases into the

atmosphere, either by reducing the sources of these gases (for example, the burning of fossil

fuels for electricity, heat or transport) or enhancing the “sinks” that accumulate and store

these gases (such as the oceans, forests and soil). The goal of climate mitigation is to avoid

significant human interference with Earth's climate. Note: when climate experts use the term

“mitigation,” they are referring to reducing greenhouse gas emissions. In a hazards context,

“mitigation” refers to reducing disaster losses.

Climate Resilience is the ability to anticipate, prepare for, and respond to hazardous events,

trends or disturbances related to climate. Improving climate resilience involves assessing how

climate change will create new, or alter current, climate-related risks, and taking steps to

better cope with these risks.

Local Handbook Update

6

Mitigation Planning is Risk-Informed Decision Making

Mitigation works best when it is based on a long-term plan that is developed before a disaster. By

assessing risk and vulnerability to hazards, mitigation planning identifies long-term local policies and

actions that communities can take to increase resilience. Effective planning also weighs input from a

wide range of stakeholders and the public. Mitigation planning:

Encourages community leaders to choose actions to reduce risk that stakeholders and the public

will support.

Focuses resources on the greatest risks and vulnerabilities, including where they are needed the

most, i.e. areas and populations disproportionately affected by disasters.

Builds partnerships with diverse stakeholders. This deepens the pool of data and resources,

which can help reduce workloads and achieve shared community objectives.

Boosts awareness of threats and hazards, including their risks and the community’s vulnerability

to those risks.

Aligns risk reduction with other community goals and programs like

capital improvements.

Supports socially vulnerable populations and underserved communities in achieving resilience.

Legislative and Strategic Basis for Mitigation Planning

The legislative authority that provides the legal authority for mitigation is derived from the

Stafford Act, as amended by the Disaster Mitigation Act of 2000. Section 322 of the Stafford

Act specifically addresses mitigation planning. This establishes the requirement that state and

local governments prepare hazard mitigation plans as a precondition for receiving FEMA

mitigation project grants.

FEMA’s 2022-26 Strategic Plan identifies empowering risk-informed decision making as a key

objective for building a climate resilient nation. The mitigation planning process involves all of

the critical components of understanding current and future risks, forming partnerships and

identifying the most appropriate actions to build climate resilience.

Planning is the Foundation for Mitigation Investments

Local mitigation plans are investment strategies that communities create through the planning

process. Plans are used to identify hazards, assess risks and vulnerabilities, and develop strategies.

The planning process is community-based and risk-informed. It closely aligns with the principles laid

out by the Comprehensive Preparedness Guide 101. The process shows the whole community why it

Local Handbook Update

7

should mitigate. It also helps communities develop actions based on their current and future risks

and capabilities.

Guiding Principles

The mitigation plan belongs to the local community. While FEMA has the authority to approve plans

so local governments can apply for mitigation project funding, there is no required format for the

plans. FEMA reviews what is in the plan, not how it is organized. When developing the mitigation

plan, keep the following principles from the Guide in mind.

Figure 3: Guiding principles for local mitigation plans.

Local Handbook Update

8

Task 1. Determine the Planning

Area, Process and Resources

1.1. Initial Considerations

1.1.1. New Plan or Plan Update

Once you decide to create a hazard mitigation plan, it’s time to set up the planning process. The

foundation of all mitigation plans is an inclusive, well-documented planning process with community

buy-in. A successful process brings diverse partners together. They will discuss your community’s

experience with natural hazards and how to meet your risk reduction needs.

The first question that needs to be answered when developing a mitigation plan is: Are you updating

a plan or creating a new one? There are instances where participants in a multi-jurisdictional plan

decide to create their own plan, resulting in a “new” plan. Additionally, single jurisdictions may see

the value of participating in an existing regional plan that is being updated. All local situations are

unique and deciding on the type of plan to develop will depend on the needs of the local community.

1.1.2. Confirm Participant(s) and Planning Area

Plans can be single- or multi-jurisdictional. Multi-jurisdictional plans require all participants to meet

certain requirements to adopt. Multi-jurisdictional plans may include local and tribal governments,

and special districts.

Communities may choose to develop their own plan or work with other communities. No matter the

configuration, all participants must meet the mitigation planning requirements.

Figure 4: Single-jurisdictional plans have only one governing body. Multi-jurisdictional plans

cover many local governments in one plan.

Local Handbook Update

9

Both single- and multi-jurisdictional plans have benefits and challenges. Single-jurisdiction plans

offer independence in how the community will design and conduct its planning process. This type of

plan can be suitable for any community, large or small.

Jurisdiction, Community and Participants

The Guide and the Handbook use the terms “jurisdiction,” “community” and “participant”

interchangeably. These terms refer to any local government developing or updating a local

mitigation plan. 44 CFR § 201.2 defines "local government" as “any county, municipality, city,

town, township, public authority, school district, special district, intrastate district, council of

governments (regardless of whether the council of governments is incorporated as a nonprofit

corporation under state law), regional or interstate government entity, or agency or

instrumentality of a local government; any Indian tribe or authorized tribal organization, or

Alaska Native village or organization; and any rural community, unincorporated town or village,

or other public entity.”

In some cases, a participant’s service area or footprint may cross political boundaries.

Examples of this include a fire protection district or a utility district.

Multi-jurisdictional plans have certain requirements that help to make sure each community goes

through its own local planning process, in addition to the overall group effort. The group planning

process will be led by the coordinating entity, referred to as the plan owner, and will include

representatives from each jurisdiction. The plan owner takes the lead for coordinating across all

participants and with the state and FEMA. Each jurisdiction will take the information shared at group

meetings, pass the information on, and collect information through their own local planning process.

Each participant must assess their unique risk to identified hazards and identify their own

capabilities to reduce those risks. Each must develop their own actions to reduce the risks specific to

their community.

Table 1: Benefits and Challenges of Multi-Jurisdictional Plans

Benefits of a Multi-Jurisdictional Plan

Challenges of a Multi-Jurisdictional Plan

Improves communication and

coordination.

Enables comprehensive and regional

mitigation approaches.

Maximizes economies of scale by sharing

costs and capabilities.

Avoids duplication of effort.

Provides organizational structure.

Broader chances for participation.

Reduces individual control over the process.

Involves coordination and administration to

track multiple independent local governments,

especially when it comes time for each local

government to adopt the plan.

Requires organizing large amounts of

information, including individualized mitigation

strategies, into a single document.

Local Handbook Update

10

If you find that a multi-jurisdictional planning effort is the best option for your community, then

decide if it is best to join an existing planning effort or take the lead on initiating a multi-jurisdictional

plan. Plan owners for multi-jurisdictional plans typically include counties, rural or metropolitan

planning organizations and planning districts. Multi-jurisdictional planning works best when

jurisdictions:

Share boundaries and have economic ties (workplaces and workforce housing, transportation,

critical infrastructure, etc.).

Face similar threats or hazards.

Work under the same authorities.

Have similar needs and capabilities.

Have worked well together in the past.

You will need to partner with neighboring jurisdictions that could be Tribal governments and/or

quasi-governmental agencies. These may include special districts that own and operate critical

infrastructure or that would like to apply for FEMA mitigation project grants. Special districts have an

interest in reducing threats and hazard impacts as many serve customers across multiple

jurisdictions. This is especially true if they provide services that are vital to recovery efforts.

Tribal Governments in Multi-Jurisdictional Plans

A federally recognized tribal government may also choose to participate in a multi-jurisdictional

plan. However, the Tribe must meet the requirements specified in 44 CFR §201.7, Tribal

Mitigation Planning, which are slightly different from the local planning requirements. Tribal

and local governments that are not federally recognized must meet the local mitigation

planning requirements specified in 44 CFR §201.6.

Indian Tribal government means any federally recognized governing body of an Indian or

Alaska Native Tribe, band, nation, pueblo, village or community that the Secretary of the

Interior acknowledges to exist as an Indian Tribe under the Federally Recognized Indian Tribe

List Act of 1994, 25 U.S.C. 479a. This does not include Alaska Native corporations, the

ownership of which is vested in private individuals.

The planning area refers to the geographic area the plan covers. Generally, the planning area follows

jurisdictional boundaries. These can include cities, townships, counties and planning districts.

However, watersheds or other natural features may also define planning areas. Communities may

choose this approach when hazards create similar risks across jurisdictional boundaries.

The State Hazard Mitigation Officer (SHMO) or state emergency management agency can help

communities determine the appropriate planning area, too. State planning goals and funding

Local Handbook Update

11

priorities may guide this decision. Keep in mind that the scale of the planning area should be

meaningful to participants to form an enduring resilience framework. For example, consider aligning

with established regional planning or economic development districts to leverage their planning

expertise.

After identifying the planning area and participating jurisdictions, it helps to get a written

commitment from all participants. Ask the jurisdictions to sign a Voluntary Participation Agreement

(VPA) at the start of the planning process. The VPA should outline requirements for each participating

jurisdiction. You can find a sample VPA for a multi-jurisdictional planning team in Annex B

.

1.1.3. Review Previous Plan and Scope Update

If you are updating your mitigation plan, read your community’s previously approved plan and the

Plan Review Tool (PRT). The plan is a baseline for understanding and updating hazards, risks and

community profiles. It can help you identify opportunities for improvement. Reading the previously

approved plan can also aid in identifying areas that may need more time and resources.

If you have a previously approved plan, FEMA completed Section 2 of the PRT during their review

process. It notes plan strengths and identifies opportunities for improvement. Let this guide your

priority areas for the plan update. Incorporating FEMA’s feedback can help you improve each

subsequent version of a plan.

Considerations for Plan Updates

Element E of the Guide lists specific requirements for plan updates. These requirements ask

communities to think about how circumstances have changed since their previous plan was

adopted. You can use these questions and considerations throughout your plan maintenance

cycle. However, they are especially crucial for the formal 5-year update.

1.2. Right-Sizing the Scope of the Planning Process

When developing a plan, it is crucial to make some key decisions about the plan’s focus and what it

will achieve, given the time and resources available. Not every planning process needs the same

level of effort to get to an approved plan. This is called right-sizing the plan. Develop a scope of work

(SOW) to outline what your planning process needs to accomplish to get to an approved mitigation

plan. An SOW is part of a FEMA mitigation planning grant application, but it can also be useful even if

you develop the plan without FEMA funding.

1.2.1. Preliminary Questions

When developing your SOW, use the questions in Table 2 to determine your needs. These questions

can help you match the plan development’s complexity to the cost and overall level of effort.

Local Handbook Update

12

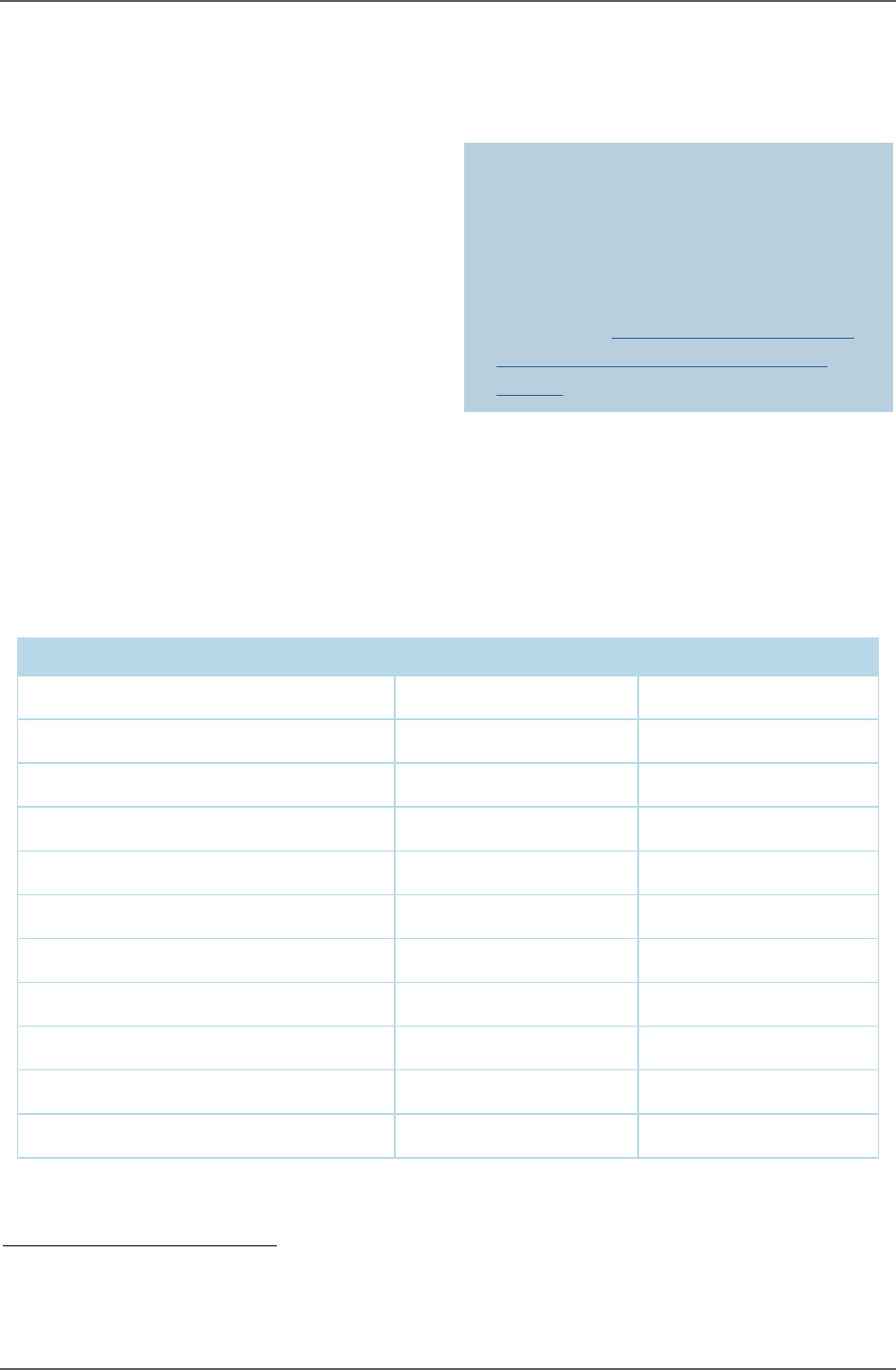

Table 2: Preliminary Considerations

Consideration Type Key Questions

Plan Configuration Is this a new plan or a plan update?

o What can be updated simply with information from the last

5 years? What requires significant rewriting?

o Are there additional data that you need to gather and

include?

How many communities will participate and are there sufficient

resources for coordination?

How many agencies and partners need to participate to bring

resources and ideas to the table? Are there sufficient resources for

coordination?

Participant Priorities What do participants want to address?

o What hazards are of most concern?

o

What are the problem areas in the community or region?

Overall Timeline Is there a tight turnaround for having an approved mitigation plan,

such as an upcoming grant deadline, or is there some additional

time?

Needed Support Can this be done in-house with existing personnel?

Can a

local college or university assist with the planning process or

data analysis?

Is t

he level of expertise needed outside of the community’s

skillset?

Will you need contractor support?

Cost

How much will the process (plan development or update) cost,

considering costs all the way through plan adoption and approval

by FEMA?

o Do you need to apply for funding?

o What federal and state programs exist that can help pay

for the plan’s development?

1.2.2. Schedule Considerations

Preparing a mitigation plan takes time. Consider a timeline of at least 18 months for taking a plan

from initiation through approval. With an 18-month timeline, it is important to be clear about the

overall level of effort up front with all participants. Start with forming an SOW that is right-sized for

the needed planning effort and can accommodate all participants, including underserved

communities and socially vulnerable populations. Get signed VPAs from all participating jurisdictions

who plan to engage with and adopt the final plan.

Local Handbook Update

13

It is also important to account for the parts of the process that add time, such as:

Findin

g and pursuing funding and/or in-kind support for the planning process and resulting

documents.

Find

ing and hiring a contractor, if needed, and following all applicable procurement rules and

processes.

Stat

e and FEMA review. Budget at least 6 months for this. Your review may not take this long, but

it is better to plan for a longer review period to avoid your plan expiring.

Ado

ption and FEMA approval. Coordination and correspondence around adoption and approval

can also add time to your schedule.

Mitigation plans are approved for a period of 5 years. To keep grant eligibility, the plan must be

updated and approved every five years. When scoping a plan update, develop the SOW and pursue

funding no later than the third year of the plan’s approval period. It can take up to 12 months to

secure funding. This means that pursuing funding in the third year will allow plenty of time to get to

an approved plan. These general timelines also apply to new plans. Pursue grant funding 3 years

before you want to have an approved plan. Remember it may take at least 18 months to develop a

plan.

Mitigation plans can be developed in a multitude of ways. Whether funding a contractor to help

complete the work, or a commitment of time and resources, there is a cost to mitigation planning.

Communities may choose to develop plans themselves, relying on local funds, time, and effort. Other

communities may lack the necessary skillsets to develop a plan themselves. In those cases, FEMA

HMA programs can provide funding to develop a mitigation plan. Coordinating with the SHMO can

help clarify which path might work best for a particular participant.

For more information on scoping considerations, watch FEMA’s Starting Your Mitigation Story with

Scoping your Mitigation Plan training and review the

Considerations for Local Mitigation Planning

Grant Subapplications Job Aid.

1.3. Organizing Resources

After you have determined your planning area, outlined the SOW, and made crucial planning process

decisions, it is time to organize your resources to support the planning process. Resources can be

your partners, data resources, plans and studies, and technical assistance.

1.3.1. People and Partnerships

The planning process is powered by staff, stakeholders and volunteers from across the private,

public and non-governmental sectors. Many partnership options can exist within a planning area.

These options can be based on current planning projects, relationships and partnerships. Think

Local Handbook Update

14

about whether your community works with regional organizations, councils of government, or other

established multi-jurisdictional partnerships for planning activities.

Creating a mitigation plan does not require formal training in community planning, engineering or

science. However, you should include subject matter experts in the planning process. Consider how

personnel or contractors can help with:

Identifying hazards, assessing vulnerabilities, and understanding significant risks.

Facilitating meetings, involving partners and the public, and decision-making activities.

Forming an organized and functional plan with maps or other graphics.

You have many options when considering outside help for plan development. You could contract with

a regional planning agency, local college or state university. You may also want to reach out to

another community that has already finished the planning process for advice. Before getting outside

help from any of these sources, consider:

The SOW, including administration, coordination and engagement.

The expertise, type and extent of help needed.

The level of interaction between support services, other members of the planning team, partners

and the public.

Private consultants are another resource. They can help you coordinate, manage and carry out the

mitigation planning process. Consultants can support facilitation, administration and documentation

of the planning process. All information should be provided by and approved by each participant. If

your community decides to hire a consultant, consider looking for a professional planning firm. Any

support services for the planning process should:

Recognize the unique demographic, geographic, technical and political considerations of each

participating community.

Show knowledge or experience with land use and community development.

Know all the policies and regulations that apply to the mitigation plan. This should include

federal law, FEMA regulations and policies, state laws and local ordinances.

Know that community input and public participation are key to any successful mitigation plan.

Have demonstrable mitigation planning experience working with underserved communities and

socially vulnerable populations.

Show familiarity with emergency management and multi-hazard mitigation, climate adaptation

and resilience concepts.

Local Handbook Update

15

Share past performance information and references

For more information on engaging the right people and partners in the planning process, see Task 2:

Build the Planning Team.

1.3.2. Plans, Studies and Data

Plans, studies and data are important inputs for the planning process. The plan must document the

current technical information, plans, reports and studies used in the plan. Incorporating these

resources makes sure you build off of the latest research and data, which leads to a stronger, more

comprehensive mitigation plan. Carefully review related documents and data. If something can help

you assess your risks, vulnerabilities and capabilities or set a strategy, include it in the plan.

Policy Connection: Element A4

Does the plan describe the review and incorporation of existing plans, studies, reports and

technical information?

1.3.2.1 INCORPORATING OTHER PLANNING MECHANISMS

Hazard mitigation planning, and community planning in general, does not happen in a vacuum. The

mitigation plan should support and be supported by other local plans and policies. This can ensure

the success of mitigation actions. It can also bolster the effectiveness of other planning mechanisms

in working toward resilience. Take the time to gather these plans and policies and see how they may

tie in to risk reduction.

Table 3: Planning Mechanisms that Support the Mitigation Plan

Planning

Mechanism

What it Supports What to Look For

Climate Action or

Adaptation Plan

Risk Assessment

Mitigation Strategy

Detailed climate projections; descriptions

of climate risks; existing climate-related

goals and actions

Comprehensive,

General, or Master

Plan

Risk Assessment

Capability Assessment

Information on hazards, development

trends, goals and policies, land use plans,

and other ordinances that support risk

reduction

Emergency

Operations Plan

Risk Assessment

Capability Assessment

Data on hazards or events of concern and

vulnerabilities

Local Handbook Update

16

Planning

Mechanism

What it Supports What to Look For

Economic

Development

Strategy or Plan

Planning Process

Risk Assessment

Mitigation Strategy

Existing partners; prioritized economic

growth areas, growth industries and their

relative risks

Emergency Action

Plan (EAP) for

Dams

Risk Assessment

High-Hazard Potential Dam

Requirements

Location and characteristics of dams;

inundation maps

Land Use

Ordinances

Risk Assessment

Capability Assessment

Hazard-specific provisions and overall

development rules

Pre-Disaster

Recovery Plan

Planning Process

Risk Assessment

Mitigation Strategy

Information on potential partners; risk

reduction plans and strategies

Before you start the planning process, find out if other planning efforts could be aligned or integrated

with the mitigation plan. This can save time and money and can also lead to better outcomes for

your community. For instance, you could fold mitigation plan development into the community’s

process for updating their comprehensive plan, economic development plan, or community wildfire

protection plan. However, keep in mind that not every planning mechanism can coordinate with your

mitigation plan.

Community Rating System (CRS) Alignment

Be sure to identify and document CRS communities (or those that plan to join in the next 5

years) early in the planning process. Many CRS communities rely on their local mitigation plan

updates for critical Activity 510 credit. While there are many overlaps between mitigation

planning and CRS requirements, there are some differences. Knowing those differences and

addressing them from the beginning will allow a community to maximize the CRS credits

earned from the mitigation plan. If the mitigation plan does not meet the CRS planning

requirements, you will need to develop a separate plan. Refer to FEMA’s Mitigation Planning

and the Community Rating System Key Topics Bulletin for more information.

More information on aligning the mitigation planning process to CRS credits can be found in

the CRS crosswalk.

1.3.2.2 FEMA RISK MAPPING, ASSESSMENT AND PLANNING (RISK MAP) PRODUCTS

The Risk MAP program supports community resilience by providing data, building partnerships, and

supporting long-term hazard mitigation planning. FEMA provides flood hazard and risk data products

Local Handbook Update

17

to help guide mitigation actions. These products fall into two categories: regulatory and non-

regulatory.

Communities use regulatory products as the basis for official actions required by the NFIP.

Traditionally, FEMA flood studies produce regulatory products for a community. These include a

Flood Insurance Study (FIS) Report and Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs) that communities use

for floodplain management purposes. The FIRMs are the official community maps that show special

flood hazard areas and flood risk premium zones. When the NFIP completes a flood study, the data

and maps are assembled into an FIS report. This report has detailed flood elevation data in flood

profiles and data tables. These maps and products can be primary sources of flood data for your

local plan. It is key to understand that flood hazards are dynamic and change over time because of

development, land use changes, climate change and other variables.

Non-regulatory products go beyond the basic flood hazard information found in the regulatory

products. These products provide a more user-friendly analysis of flood risks within a Risk MAP Flood

Risk Project. They include:

Changes Since Last FIRM. This shows changes made to the regulatory floodplain and floodway

during a map update.

Water Surface Elevation Grids. This dataset allows the user to find flood elevations for the entire

floodplain.

Flood Depth Grids. These illustrate the varying flood depths in flood prone areas.

Percent Annual Chance Grids. These display the likelihood that a given location will flood in any

single year.

Not every community receives both regulatory and non-regulatory products. The FEMA Map Service

Center is the best place to find these materials. Communities should review the products available

for their area when beginning or updating a mitigation plan.

1.3.3. Technical Assistance

Some parts of the planning process or plan preparation can benefit from technical assistance. If you

need outside technical assistance to help form the plan, think about how to use that aid to build

long-term community capabilities. Creating a mitigation plan does not require formal training in

community planning, engineering or science. However, subject matter experts should be included in

the planning process. Consider how personnel or contractors can help with:

Identifying hazards, assessing vulnerabilities and understanding significant risks.

Facilitating meetings, partner and public involvement, and decision-making activities.

Forming an organized and functional plan with maps or other graphics.

Local Handbook Update

18

Both states and FEMA provide training and technical assistance to local governments as a part of

their mission. The state is responsible for providing training and technical assistance in applying for

HMA grants and developing mitigation plans. To better understand what kind of technical assistance

may be available to your local community, reach out to your SHMO

.

Different grant programs may also provide some level of technical assistance based on the grant

type and potential project. The Building Resilient Infrastructure and Communities (BRIC) grant

program offers non-financial direct technical assistance. This can provide mitigation planning help.

Local Handbook Update

19

Task 2. Build the Planning Team

2.1. Building the Planning Team

The second key task at the start of the planning process is to bring together a diverse and inclusive

planning team. These representatives should come from each participating jurisdiction and partner

organization, especially those with data, funding sources or comprehensive local knowledge. As

discussed in Task 1

, these planning partners have the necessary expertise to inform the plan.

Additionally, partner organizations may have the authority to carry out the mitigation strategy

developed through the planning process. The planning team is the core group of people responsible

for:

Developing and reviewing drafts of the plan.

Informing the risk assessment.

Developing the mitigation goals and strategy.

Submitting the plan for local adoption by each participant.

Many local agencies have an interest in, and tasks related to, mitigation. The planning process

should include these agencies. For example, emergency management and community planning staff

in local government have unique knowledge and skills. These skillsets make them potential leaders

for the planning process. Local emergency management staff know area-specific threats, hazards,

risks, vulnerabilities and past occurrences. They may also have more experience working with state

and federal agencies on mitigation projects and activities. Community planning staff are familiar with

zoning and subdivision regulations, land use plans, economic development initiatives, climate

adaptation and resilience plans and projects, and long-term funding and planning mechanisms to

carry out mitigation strategies. They may be trained to do public outreach, lead and facilitate

meetings and develop a plan.

Community development and emergency management staff can lead the development of a local

mitigation plan. Other departments may be able to do the same. When determining leadership, think

about who has the time and resources to commit to the whole planning process. It can be helpful to

designate a lead jurisdiction who is handling all the coordination for the plan. Each jurisdiction in a

multi-jurisdictional plan should have a lead representative to coordinate its planning process, engage

partners and conduct public outreach.

2.1.1. Multi-Jurisdictional Planning Team

If you are developing a multi-jurisdictional plan, creating a group planning team structure that allows

for coordination and accountability between jurisdictions is key. If using this approach, each

jurisdiction should have at least one representative on the planning team. This representative will

Local Handbook Update

20

coordinate and delegate any tasks within their part of the planning area. They should also manage

the inputs and content (including public outreach and engagement) they contribute to the plan. Each

participating jurisdiction, including special districts, will need to meet the requirements to be able to

adopt the plan. This means being an active participant in the planning process. It also means

providing local context and detail, as well as reviewing the draft plan and providing comments.

Not every planning team will be the same. The structure of the planning team depends on the needs

of local participants. Think about different types of organizational structures when you form your

planning team. This could include a planning committee divided into one steering committee and

one separate planning team for each participating jurisdiction. The core planning group can manage

the overall plan activities. It can also directly help with the decision-making process.

Some planning teams may have a single point of contact (POC) or representative for each

jurisdiction. Others may have more than one. Even if the planning team has more than one

representative from a particular jurisdiction, it is a good idea to designate one lead POC for each

jurisdiction. This person will report back to their departments, partners and the public on a regular

basis. They will also gather feedback and input for the plan from stakeholders.

Requirements for Multi-Jurisdictional Plans

Any jurisdiction or organization may join in the planning process. However, to request FEMA’s

approval of the plan and thus be eligible for HMA grants, each local jurisdiction must meet all

of the requirements of 44 CFR §201.6. In addition to the requirement for participation in the

process, each jurisdiction in a multi-jurisdictional plan must show that they have done the

following:

Identified hazards specific to their jurisdiction and addressed specific vulnerabilities (each

jurisdiction’s risk likely differs from those of the entire multi-jurisdictional planning area).

Discussed their participation in the NFIP and identified repetitive loss properties.

Developed mitigation action items that addressed each identified hazard.

Identified opportunities for integrating the completed plan into other planning

mechanisms.

Addressed changes in development since the last plan and how this affected vulnerability

(plan updates only).

Provided the status of all previous mitigation actions (plan updates only).

Formally adopted the plan.

Any participating jurisdiction that develops mitigation actions in the plan must identify what

its capabilities are to support the mitigation strategy.

Local Handbook Update

21

The mitigation plan must clearly list the jurisdictions that participated in the plan and are

seeking plan approval. It also helps to include a map of the planning area with jurisdictional

boundaries marked.

2.1.2. Identify Planning Team Members

When building the mitigation planning team, start with existing community organizations or

committees. For mitigation plan updates, bring together as many members of the team from the last

planning process as possible. Add in any new individuals or organizations. A committee that

oversees the comprehensive plan or addresses issues related to land use, transportation or public

facilities can be a strong foundation for your team.

Adding in a diverse array of planning team members can create a comprehensive view of how

threats and hazards affect:

Economic development.

Housing, health and social services.

Infrastructure.

Natural and cultural resources.

Underserved communities and socially vulnerable populations.

You can also build on your community’s Local Emergency Planning Committee

(LEPC). This group

deals with hazardous materials safety and may also address other threats and natural hazard

issues. In small communities, LEPCs may comprise the same people and organizations that the

mitigation planning team needs.

2.1.2.1 REQUIRED STAKEHOLDERS

Stakeholders are individuals or groups that a mitigation action or policy affects. Stakeholders may

include businesses, private organizations and residents. Involving them in the planning process

helps to gain support for the plan and identify barriers to carrying it out.

It is crucial to distinguish between those who should serve as members of the planning team and

other stakeholders. Planning team members work in all stages of the planning process; stakeholders

may not. However, they can advise the planning team on a specific topic. They can also give input

from varied points of view in the community.

Some stakeholders must have the chance to be on the planning team or otherwise involved in the

planning process:

Local Handbook Update

22

Local and regional agencies involved in hazard mitigation activities. Examples include public

works, emergency management, local floodplain administration and Geographic Information

Systems (GIS) departments.

Agencies that have the authority to regulate development. Examples include zoning, planning,

community and economic development departments, building officials, planning, commissions

and other elected officials.

Neighboring communities. Examples include adjacent local governments, including special

districts and tribes, that are affected by similar hazard events. They also may share a mitigation

action or project that crosses jurisdictional boundaries.

Businesses, academia and other private interests. Examples include private utilities, chambers

of commerce, dam owners, local or regional educational centers within the jurisdiction, or major

employers that sustain community lifelines.

Nonprofit organizations, including community-based organizations, that work directly with and/or

provide support to underserved communities and socially vulnerable populations. It is key to

bring partners to the table who can speak to the unique needs of these groups. They can make

sure the planning process supports these populations and includes their voices in the plan.

These groups may include:

o Faith-based organizations.

o Disability services agencies or non-governmental organizations (NGOs).

o Rural support agencies.

o Health and social services departments.

o Housing agencies and housing advocacy groups.

An opportunity to be involved in the planning process means that these stakeholders are invited to

participate. It could also mean they are asked to share information or input to inform the plan’s

content. Some communities may need more targeted outreach and engagement. This is especially

true of underserved communities. Outreach and engagement efforts should respond to the

communities’ specific needs. For instance, some community members may lack access to high-

speed internet. As such, they may not be able to access websites, social media campaigns, email

newsletters or virtual meetings.

Spotlight on High Hazard Potential Dams

The Water Infrastructure Improvements for the Nation Act added the Rehabilitation of High

Hazard Potential Dams (HHPD) grant program that includes all dam risks.

Local Handbook Update

23

To be eligible for HHPD grants, local governments must have:

Jurisdiction over the area of an eligible dam.

An approved local mitigation plan that includes all dam risks and complies with the

Stafford Act, as amended.

When designing the planning process, localities must engage the state dam safety agency

and/or dam owners. These partners will have data to support addressing and reducing risks to

and from dams in the planning area. The plan must describe how these partners participated

and what data they provided. To be eligible for HHPD funding, bring these partners into the

planning process early and engage them often.

The Guide outlines the full HHPD requirements to have an approved local mitigation plan that

includes all dam risks. Those elements include the planning process, risk assessment, etc. The

full list is in Section 4.7 of the Guide. The HHPD requirements do not need to be addressed in

a separate section of the plan. They can be woven into the appropriate section. For multi-

jurisdictional plans, consider meeting the requirements for all participating jurisdictions,

including special districts.

To meet requirement HHPD1, the local mitigation plan must:

Describe how the local government coordinated with local dam owners and/or the state

dam safety agency.

Document the information shared by the state and/or local dam owners. Examples may

include:

- Location and size of the population at risk, as well as potential impacts to institutions

and critical infrastructure/facilities/lifelines.

- Inundation maps, EAPs, floodplain management plans and/or data, or summaries

provided by dam breach modeling software, such as HEC-RAS, DSS-WISE HCOM, DSS-

WISE Lite, FLO-2D, as well as more detailed studies.

2.1.2.2 COMMUNITY LIFELINE STAKEHOLDERS

Stakeholders should also include people who represent community lifelines. Community lifelines are

the vital services in a community. When stabilized, they enable all other aspects of society to

function. Think about the agencies or companies that represent your community’s lifelines and invite

them to be a stakeholder for your mitigation plan.

Local Handbook Update

24

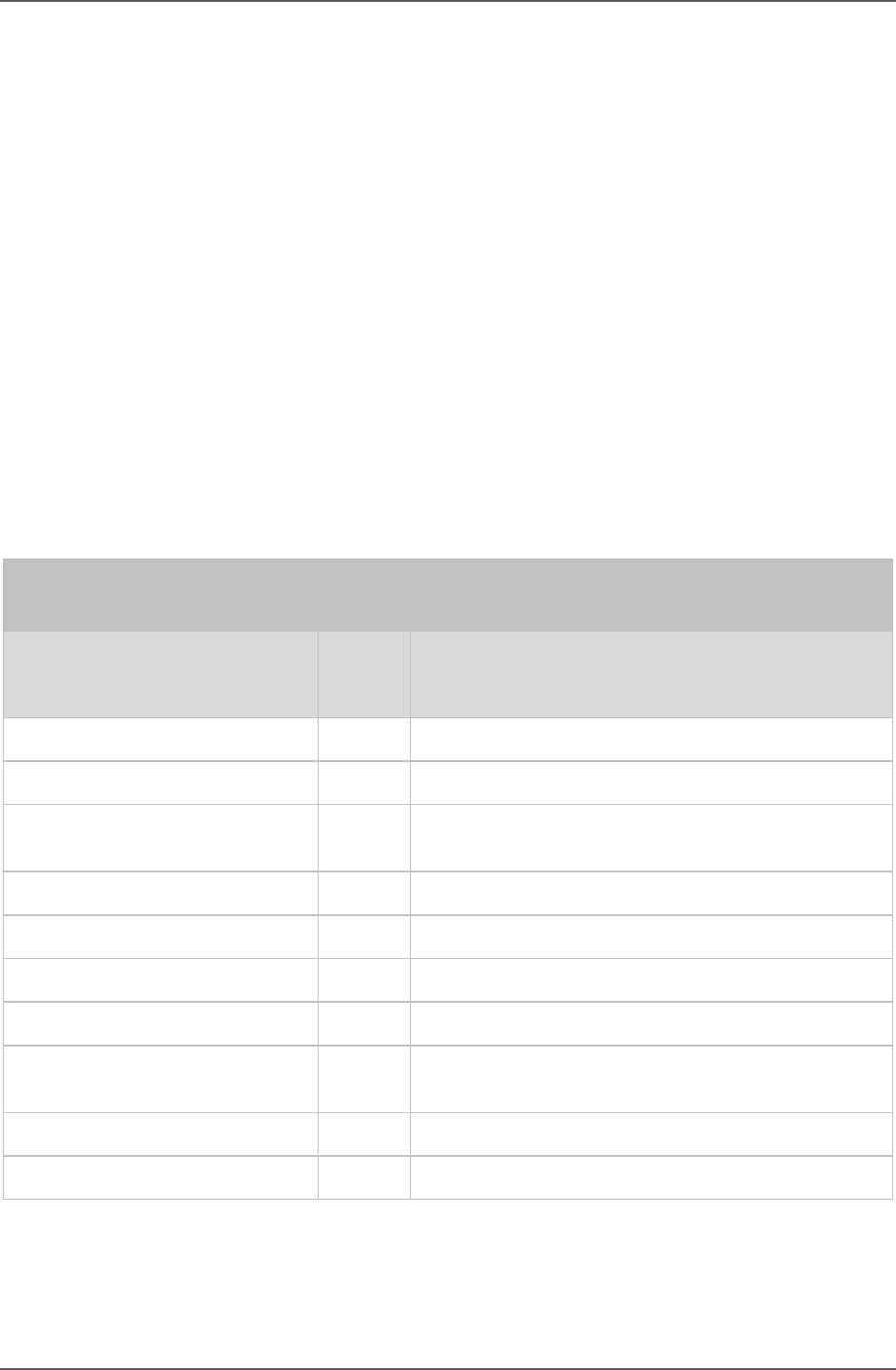

Table 4: Community Lifeline Stakeholder Contributions to the Plan

Lifeline Example(s)

Safety and Security

Law enforcement, police

stations, site security, fire

service, search and rescue,

government service

(emergency operations

centers, government offices,

schools, historic/cultural

resources), community

safety.

Provide first-hand

knowledge of past hazard

events and response

systems.

Connect the mitigation plan

to the Threat and Hazard

Identification Risk

Assessment (THIRA)

planning process and vice

versa.

Share data on lifeline

locations, protection

measures and capabilities

that support local resilience.

Hazardous Materials Oil and HAZMAT facilities.

Food, Water, Shelter

Food distribution programs,

commercial food supply

chain, drinking water utilities,

wastewater systems, housing

and commercial facilities,

animals and agriculture.

Coordinate housing issues

to identify risk and

vulnerabilities to this sector

and lifeline.

Ensure the mitigation

strategy directs new and

redeveloped housing away

from hazard areas and uses

the latest building codes to

maintain safe housing.

Use the planning process to:

o Understand high-risk

areas and at-risk

populations.

o Increase awareness of

potential funding to

support housing

development and

maintaining Food,

Water, and Shelter

lifelines.

Share data on lifeline

locations, protection

measures, and capabilities

that support local resilience.

Local Handbook Update

25

Lifeline Example(s)

Health and Medical

Medical care, hospitals,

pharmacies, home care,

public health services,

emergency medical services,

medical supply chain, fatality

management services.

Help the planning team

understand social

vulnerability in the

community, including

underlying stressors.

Help identify actions and

projects that reduce risk

exposure for underserved

communities and socially

vulnerable populations.

Link socially vulnerable

populations or the

organizations that serve

them to grants and other

assistance, before and after

a disaster.

Connect traditional health,

medical and social services

and mitigation funds.

Integrate mitigation into the

disaster recovery process.

Share data on lifeline

locations, protection

measures, and capabilities

that support local resilience.

Energy

Power grid generation,

transmission, and distribution

systems, fuel processing,

storage, pipelines, and

distribution.

Identify at-risk infrastructure

assets, including

transportation, energy,

communications, water

conveyance and supply

chains.

Develop and prioritize

mitigation actions for at-risk

assets.

Transportation

Highways, roads, bridges,

mass transit, railway,

aviation, maritime.

Local Handbook Update

26

Lifeline Example(s)

Communications

Infrastructure (wireless,

cable, broadcast, satellite,

internet), responder

communications, alerts,

warnings, and messages,

financial banking services,

911 and dispatch.

Integrate resilience into

infrastructure investment

decisions.

Share data on lifeline

locations, protection

measures, and capabilities

that support local resilience

of infrastructure (highways,

roads, bridges, mass transit,

railway, aviation, maritime).

Develop and prioritize

mitigation actions for at-risk

assets.

Integrate resilience into

infrastructure investment

decisions.

Share data on lifeline

locations, protection

measures, and capabilities

that support local resilience

(cable, broadcast, satellite,

internet)

Develop and prioritize

mitigation actions for at-risk

assets.