What's

in

a

name?

Robbie

was

rightly

and

loyally

devoted

to

his

family

name.

When

he

accepted

a

knighthood

at

the

second

time

of

its

being

offered

to

him

I

asked

him

what

he

was

to

be

called-Robbie,

Robin,

Robert,

or

Theodore?

"Well,"

he

said,

"what

was

inappropriate

as

a

name

for

me

at

my

prep

school

might

now

come

into

use."

So

Sir

Theodore

he

became.

"Your

father

would

have

been

pleased,"

I

said.

"Did

you

know

my

father?"

he

asked.

I

did

not.

But

I

knew

that

as

Dr

Fortescue

Fox

of

Strathpeffer

spa

he

had

been

a

lifelong

hero

of

my

95

year

old

grandmother

for

long

after

she

had

been

able

to

pay

her

yearly

visit

to

him

for

treatment

of

her

arthritis.

Just

as

Dr

Fortescue

Fox

was

a

hero

of

my

grandmother,

so

his

son

Theodore

is

a

hero

of

mine.

Sir

Theodore

Fox

died

in

1989;

obituaries

were

published

in

the

BMJ

(1

July,

p

47)

and

Lancet

(1

July,

p

56).

Medical

imagery

in

the

art

of

Frida

Kahlo

David

Lomas,

Rosemary

Howell

Frida

Kahlo

held

her

first

solo

exhibition

in

New

York

in

1938.

Included

were

paintings

that

narrate

her

experience

of

a

miscarriage

six

years

earlier

in

Detroit,

where

she

had

accompanied

her

husband,

the

Mexican

mural

painter

Diego

Rivera.

Reviewing

the

exhibition

Howard

Devree,

an

art

critic

for

the

New

York

Times,

dismissed

Kahlo's

work

as

"more

obstetrical

than

aesthetic."'

Underlying

this

reproach

is

an

attitude

that

art

should

not

concern

itself

with

obstetrics,

a

view

that

any

cursory

glance

at

Western

art

would

confirm.

To

describe

artistic

creation

by

using

metaphors

of

gesta-

tion

and

birth

is

commonplace,

yet

to

depict

such

events

is

tacitly

proscribed.

In

Western

art

scenes

of

childbirth

are

rare

and

visual

accounts

of

abortion

or

miscarriage

non-existent.

They

have

remained

the

province

of

medical

texts.

Openly

flouting

this

conven-

tion,

Kahlo

produced

a

unique

body

of

images

such

that

Rivera

could

proclaim

her

"The

only

human

force

since

the

marvellous

Aztec

master

sculpting

in

black

basalt

who

has

given

plastic

expression

to

the

pheno-

menon

of

birth."2

In

the

culture

to

which

Kahlo

belonged

miscarriage

was

a

source

of

shame:

the

abject

failure

of

a

socially

conditioned

expectation

of

motherhood

and

a

travesty

of

creation

in

which

birth

yields

only

death

and

detritus.

No

rituals

exist

to

commemorate

the

loss

associated

with

miscarriage,

which

is

thus

relegated

to

a

private

domain

of

silent

grief.3

By

speaking

out

Kahlo

FIG

I

-HerFrosia,92CletinoDlrsleoMxcoCt

FIG

1

Heniy

Ford

Hospital,

1932.

Collection

of

Dolores

Olmedo,

Mexico

City

articulated

the

unspeakable

in

a

hybrid

language

derived

partly

from

artistic

traditions

but

also

from

textbooks

of

anatomy

and

obstetrics.

Kahlo's

medical

history

is

a

catalogue

of

misfortune.

She

was

born

in

1907

and

was

affected

by

poliomyelitis,

which

left

her

right

leg

withered

and

her

spine

scoliotic.

When

she

was

18

a

tram

accident

caused

devastating

injuries.

She

was

impaled

through

her

pelvis

by

a

steel

bar

and

sustained

multiple

fractures

of

the

spine,

pelvis,

right

leg,

and

foot.

In

subsequent

years

she

underwent

numerous

orthopaedic

operations

in

vain

atttempts

to

alleviate

pains

in

her

back

and

right

leg,

which

was

eventually

amputated.

Her

death

at

age

47

followed

soon

afterwards.

More

than

one

pregnancy

was

terminated

by

therapeutic

abortion,

and

she

had

two

(possibly

three)

first

trimester

miscarriages

of

uncertain

relation

to

the

accident.

Though

the

severe

penetrating

injury

may

have

caused

uterine

deformity,

her

debilitated

physical

state

manifesting

in

chronic

infections

and

anaemia

was

a

more

probable

contribu-

tory

factor.

Her

best

documented

pregnancy

was

proceeded

with

only

after

much

equivocation

and

weighing

of

the

potential

risks

of

a

caesarean

section.

It

ended

abruptly,

however,'in

a

miscarriage

in

1932.

Henry

Ford

Hospital

(fig

1)

was

painted

shortly

afterwards.

Kahlo

lies

naked

on

a

hospital

bed

in

a

pool

of

blood.

The

title

alludes

to

the

medical

setting

yet

her

bed

is

displaced

into

a

desolate

landscape

to

heighten

the

sense

of

isolation

and

vulnerability.

Superimposed

on

this

scene

is

an

array

of

objects

referring

to

the

miscarriage;

some

evoke

it

literally

while

others

allude

more

obliquely

and

subjectively

to

the

event.

These

are

depicted

in

a

larger

scale

and

a

contrasting

diagrammatic

idiom.

In

this

painting

Kahlo

is

the

hapless

victim

of

an

event

over

which

she

exerts

no

control.

The

impression

of

helpless

isolation

is

aggravated

by

the

lack

of

a

visual

language

to

express

her

trauma.

The

awkward

dis-

juncture

between

two

pictorial

modes-schematic

and

naturalistic-seems

to

gesture

towards

a

grief

that

is

representable

only

as

discontinuity.

Where

the

news-

paper

critic

recoiled

in

distaste

before

this

spectacle

one

sees

Kahlo

striving

to

render

visible

a

blindspot

of

high

cultural

vision.

Medical

imagery

helps

her

to

achieve

this;

immediately

after

the

miscarriage

she

began

foraging

in

obstetric

texts

and

evidently

drew

the

fetus

and

pelvis

from

this

source.

Yet

its

incapacity

to

evoke

the

subjective

dimension

of

her

response

is

indicated

by

the

sharp

discrepancy

between

these

prosaic

forms

and

the

snail,

a

private

allusive

reference.

Frida

and

the

Miscarriage,

1932

(fig

2)

has

a

similar

composition.

The

naked

body

is

central

and

once

again

surrounded

by

axially

arranged

forms:

a

fetus

(the

umbilical

cord

wrapped

like

a

bandage

around

her

damaged

right

leg),

dividing

cells,

and

growing

plants.

The

effect

is

harmoniously

balanced,

however,

where

formerly

it

was

disjointed.

Leaves

shaped

like

phalluses

Courtauld

Institute

of

Art,

London

WC2

David

Lomas,

MA,

postgraduate

student

Queen

Charlotte's

and

Chelsea

Hospital,

London

W6

OXG

Rosemary

Howell,

MRCOG,

registrar

Correspondence

to:

Mr

D

Lomas,

119

Swan

Court,

Flood

Street,

London

SW3

5RY.

BrMed3r

1989;299:1584-7

1584

BMJ

VOLUME

299

23-30

DECEMBER

1989

and

hands

echo

equivalent

shapes

of

the

fetus

opposite.

k.

.4_

The

mutually

excluding

worlds

of

female

procreation

and

masculine

artistic

creation

(Kahlo

holds

aloft

an

artist's

palette)

reunite

in

her

body,

which

is

assimilated

to

cyclical

forces

of

nature.

Tears

suspended

like

jewels

from

her

cheeks

become

raindrops

and

the

moon

;

weeps

in

unison

with

Kahlo,

who

no

longer

stands

utterly

alone.

Her

pictures

are

replete

with

wombs

and

lactating

breasts,

symbols

of

maternal

fecundity,

yet

Kahlo

departs

from

a

facile

stereotype

of

womanhood

to

register

a

more

complex

reality.

Pregnancy

was,

on

one

level,

much

desired

by

her

but

was

fraught

with

risk

and

brought

only

pain

and

distress.

Her

ambivalence

can

be

gauged

in

a

third

image

related

more

distantly

to

the

miscarriage,

My

Birth,

1932

(fig

3).

Painted

shortly

after

her

mother's

death,

it

conflates

two

chronologically

separate

events

by

representing

her

both

giving

birth

and

being

born.

A

picture

of

The

Mater

Dolorosa-the

mother

of

Christ

whose

grief

for

her

lost

son

is

shown

by

tears

and

flesh

pierced

by

daggers'-symbolically

substitutes

for

the

mother

4

.~

~

~ ~ ~ ~ ~ ~

~~

x

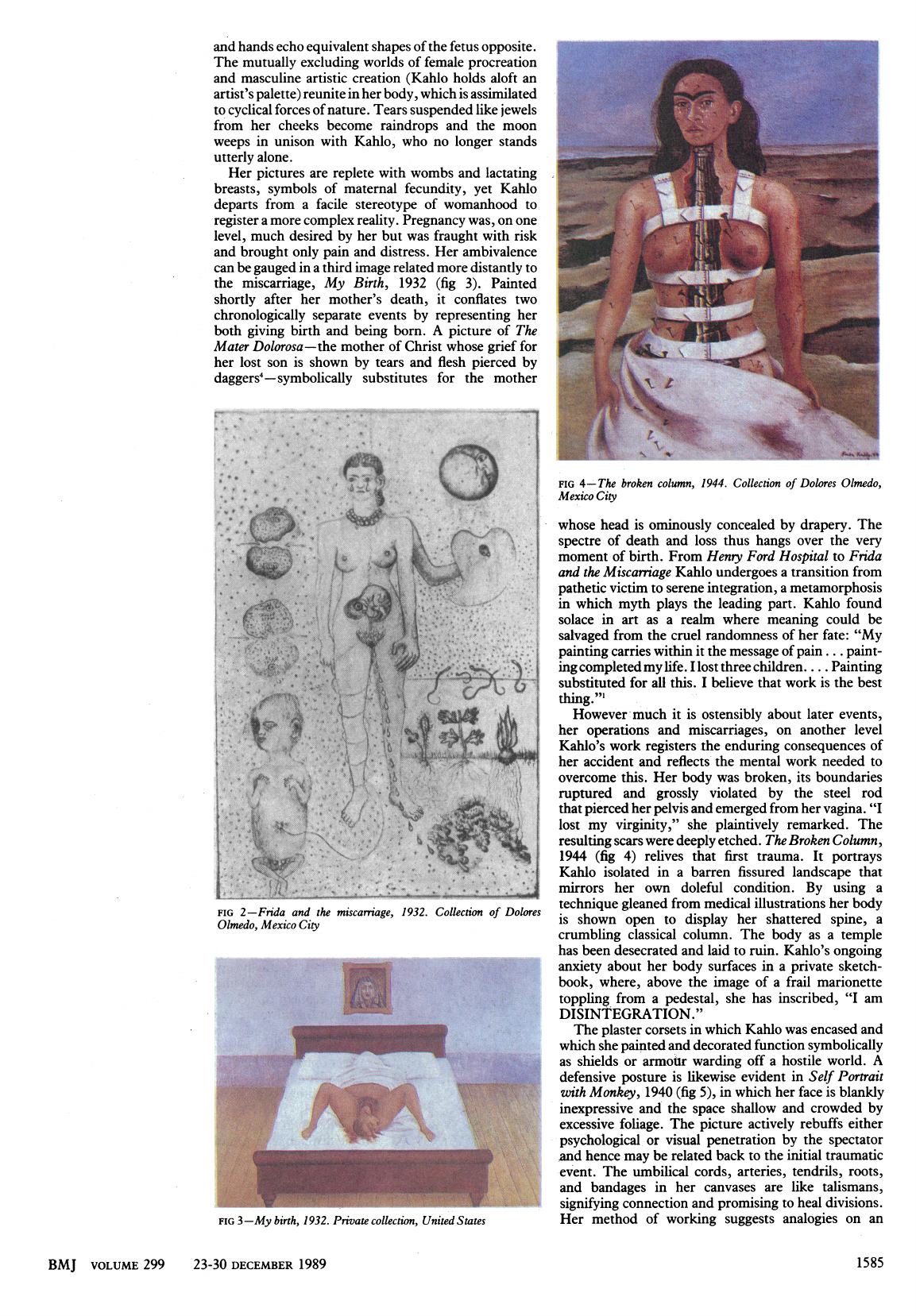

FIG

4-The

broken

column,

1944.

Collection

of

Dolores

Olmedo,

Mexico

City

whs

ead

is

ominously

concealed

by

drapery.

The

spectre

of

death

and

loss

thus

hangs

over

the

very

moment

of

birth.

From

Henry

Ford

Hospital

to

Frida

and

the

Miscarmrage

Kahlo

undergoes

a

transition

from

/

pathetic

victim

to

serene

integration,

a

metamorphosis

in

which

myth

plays

the

leading

part.

Kahlo

found

solace

in

art

as

a

realm

where

meaning

could

be

salvaged

from

the

cruel

randomness

of

her

fate:

"My

painting

carries

within

it

the

message

of

pain

...

paint-

ing

completed

my

life.

I

lost

three

children....

Painting

rizi

i

imi

01

NW.

substituted

for

all

this.

I

believe

that

work

is

the

best

thing."

However

much

it

is

ostensibly

about

later

events,

her

operations

and

miscarriages,

on

another

level

Kahlo's

work

registers

-the

enduring

consequences

of

her

accident

and

reflects

the

mental

work

needed

to

Olmedo

Mexcoovercome

this.

Her

body

was

broken,

its

boundaries

cruptured

and

grossly

violated

by

the

steel

rod

that

pierced

her

pelvis

and

emerged

from

her

vagina.

"I

lost

my

virginity,"

she

plaintively

remarked.

The

resulting

scars

were

deeply

etched.

The

Broken

Column,

1944

(fig

4)

relives

that

first

trauma.

It

portrays

Kahlo

isolated

in

a

barren

fissured

landscape

that

'~~~

~mirrors

her

own

doleful

condition.

By

using

a

FIG

2

Frwda

and

the

micarage1932Colecton

Dolorestechnique

gleaned

from

medical

illustrations

her

body

.lltnof

D

is

shown

open

to

display

her

shattered

spine,

01medo)

Mexico

City

~~~crumbling

classical

column.

The

body

as

a

temple

has

been

desecrated

and

laid

to

ruin.

Kahlo's

ongoing

anxiety

about

her

body

surfaces

in

a

private

sketch-

book,

where,

above

the

image

of

a

frail

marionette

toppling

from

a

pedestal,

she

has

inscribed,

"I

am

DISINTEGRATION."

The

plaster

corsets

in

which

Kahlo

was

encased

and

illih

a

'-

~

~~~~~~which

she

painted

and

decorated

function

symbolically

_

<

Y

=

as

shields

or

armotr

warding

off

a

hostile

world.

A

defensive

posture

is

likewise

evident

in

Self

Portrait

_

with

Monkey,

1940

(fig

5),

in

which

her

face

is

blankly

mV

inexpressive

and

the

space

shallow

and

crowded

by

excessive

foliage.

The

picture

actively

rebuffs

either

psychological

or

visual

penetration

by

the

spectator

and

hence

may

be

related

back

to

the

initial

traumatic

event.

The

umbilical

cords,

arteries,

tendrils,

roots,

d

and

bandages

in

her

canvases

are

like

talismans,

_

signifying

connection

and

promising

to

heal

divisions.

FIG

3-My

birth,

1932.

Private

collection,

United

States

Her

method

of

working

suggests

analogies

on

an

BMJ

VOLUME

299

23-30

DECEMBER

1989

1585

imaginative

plane

with

the

surgery

that

aimed

at

4

restoring

her

disrupted

physical

self.

According

to

an

acquaintance,

"They

had

to

put

her

back

in

sections

as

if

they,were

making

a

photomontage,"'

and

it

is

in

the

form

of

piecemeal

collages

that

her

paintings

are

constructed.

In

Self

Portrait

with

Dr

Farill,

1951

(fig

6)

painted

as

a

thanks

offeri

g,

this

analogy

is

ex,plicit

as

her

brushes,

drippingred

paint,

evoke

surgical

scalpels.

The

incorporation

of

overtly

medical

iconography

into

Kahlo's

painting

has

thus

far

been

treated

as

an

incidental

element

subordinate

to

the

aim

of

articulating

.

her

experience.

Yet

its

importance

far

exceeds

this

.

Kahlo

began

using

medical

imagery

in

1932

just

as

Rivera

was

painting

the

Detroit

murals

that

include

a

panel

devoted

to

modern

science

and

medicine.

A

pamphlet

describes

him

painting

on

a

scaffold

l

"littered

with

specimens

of

the

objects

he

chose

to

represent.

Strewn

about

him

were

fossils,

crystals,

fruits,

vegetables,

books

on

anatomy.5

Kahlo

too

gathered

texts

of

anatomy

and

obstetrics

and

in

her

bedroom

kept

a

fetus

in

a

jar

of

formaldehyde-a

lugubrious

gift

from

her

friend

Dr

Eloesser.

Rivera

FIG

7

-

Letter

to

A

lejandro

Gomez

Arias

IX,

1946.

Private

collection,

Mexico

City

may

have

provided

the

initial

impetus,

but

there-is

a

'

~~~vast

disparity

between

their

use

of

medical

imagery.

In

1943-4

Rivera

painted

two

murals

of

the

history

of

cardiology

for

the

Instituto

Nacional

de

Cardiologia

in

Mexico

City.

His

brief

for

the

project

dictated

that

the

ascent

of

knowledge

be

represented

by

a

pantheon

of

"cmen

striving,

striving

in

an

upward

march."

The

murals

are

dedicated

to

Dr

Chiivez,

who

was

inspired

to

write:

"Science

was

not

born

today,

nor

yesterday;

it

has

been

gestated

painfully

through

the

centuries

in

the

thought

of

man.

The

pain

of

birth

and

the

Faustian

j'oy

of

creation

join

at

each

of

the

stellar

moments

of

scientific

history

when

an

idea,

a

theory

or

a

discovery

-comes

into

being."

The

florid

metaphor

of

gestation

and

birth

has

a

cutting

edge

as

only

a

single

woman

is

included-

a

patient.

FIG

5

-Self

portrait

with

monkey,

1940.

Collection

of

Otto

Atencto

Diego

depicts

the

birth

of

cardiology

while

-Frida

Troconis,

Caracas

paints

scenes

of

actual

childbirth.

Where

the

former

are

hugely

and

heroically

masculine,

the

latter

are

modest

in

scale

and

unheroic

and

speak

of

female

experience.

In

the

murals

artistic

modernism

reinforces

AL

the

theme

of

medical

progress;

art

and

science

are

locked

in

a

mutually

uplifting

embrace.

Kahlo,

by

.mcontrast,

uses

medical

imagery

in

a

disruptive

way

as

a

foreign

element

that

causes

one

to

question

the

boun-

daries

and

exclusions

enforced

by

art.

Ironically,

as

an

adolescent

Kahlo

had

embarked

on

a

course

of

study

leading

to

medical

school,

but

her

accident

prevented

her

from

pursuing

this

career.

Yet

as a

patient

she

later

overcomes

her

dependency

on

medical

authority

by

pastiche

and

appropriation

of

its

-language.

In

a

letter

written

after

her

operation

for

spinal

fusion

in

1946

she

encloses

a

casual

sketch

(fig

7)

in

the

distinctive

style

and

format

of

medical

notation

to

depict

the

wounds

on

her

back.

Furthermore,

it

adopts

the

doctor's

viewpoint

to

scrutinise

her

body

from

a

position

that

was

physically

denied

her

as

a

FIG

6-Selfportrait

with

DrJuan

Farill,

1951.

Collection

of

Gallery

patient.

By

this

inversion

she

negotiates

a

degree

of

Arvil,

Mexico

City

autonomy,

at

least

within

the

field

of

visual

representa-

BMJ

VOLUME

299

23-30

DECEMBER

1989

1586

tion.

A

similar

strategy

can

be

discerned

in

other

images.

In

My

Birth

Herrera

notes

that

the

scene

is

examined

from

the

position

of

a

medical

attendant,'

a

viewpoint

often

used

to

depict

childbirth

in

obstetric

texts.

Here

the

device

also

heightens

the

shocking

candour

of

the

image.

The

knowledge

Kahlo

sought

about

her

body,

"Who

knows

what

the

devil

is

going

on

inside

me,"

was

illicit:

her

biographer

recounts

that

after

her

first

miscarriage

she

begged

staff

to

give

her

textbooks

with

illustrations

of

the

event

but

was

refused.'

A

complement

to

this

knowing

and

ironic

mimicry

to

a

forbidden

medical

genre

is

her

parody

of

gender.

The

Self

Portrait

with

Cropped

Hair,

1940,

best

known

of

her

many

portraits,

was

painted

while

estranged

from

Diego.

In

it

she

mockingly

dons

an

oversized

suit

belonging

to

Rivera

as

if

to

deflate

his

mythical

larger

than

life

bravado.

The

significance

of

Kahlo's

appropriation

of

medical

imagery

is

bound

up

with

the

contradictory

predica-

ment

of

a

female

intellectual

in

the

1930s.7

Because

of

her

association

with

Rivera

she

gained

entrance

to

an

emancipated,

secular

milieu

of

artists

and

intellectuals

where

scandal

was

courted

and

that

afforded

her

considerable

latitude

to

confroflt

and

affront

conven-

tional

mores.

Maybe

she

was

able

to

exploit

the

privileged

status

of

medical

imagery

to

expose

parts

and

functions

of

the

body

that

decorum

normally

hides

and

thus

sidestep

the

strictures

of

a

chauvinist,

Catholic

society.

In

Henry

Ford

Hospital

Kahlo

dared

to

display

not

only

her

naked

body

in

public

but

her

soiled

linen

too.

The

foregoing

images

openly

declare

their

medical

sources

to

underline

the

act

of

appropriation.

In

contrast,

Self

Portrait

with

Monkey

contains

a

more

veiled

reference

to

the

medical

texts

Kahlo

so

assidu-

ously

scoured,

but

which

is

none

the

less

integral

to

the

pictorial

effect.

The

red

ribbon

that

winds

round

her

neck

confers

an

air

of

foreboding

and

surely

refers

to

obstetric

images

of

cord

strangulation,

in

which

the

lifeline

of

a

fetus

becomes

the

instrument

of

its

death.

Beneath

the

lavishly

painted

surface

and

behind

her

seemingly

impassive

mask

lurks

a

sense

of

impending

doom.

Small

wonder

the

surrealist

poet

Andre

Breton

would

describe

her

art

as

a

ribbon

around

a

bomb.8

Thus

one

is

returned

to

Kahlo's

self

portraits.

The

frank

intimacy

of

her

painting

almost

inevitably

dictates

a

biographical

reading.

Against

the

grain

of

allegorical

painting

she

stridently

asserts

the

validity

of

her

concrete

experience

as

a

subject

for

art.

The

presence

of

a

particularised

subject

in

Frida

and

the

Miscarriage,

where

an

anonymous

female

figure

would

usually

appear,

exemplifies

this.

While

the

events

she

depicts

are

intensely

personal

the

language

of

their

expression

is

not.

It

is

a

paradox

that

given

her

avowed

rejection

of

Catholicism

Kahlo

constantly

draws

on

its

rich

visual

traditions;

the

tears,

wounds,

and

broken

hearts

are

those

of

the

Mater

Dolorosa,

whom

she

repeatedly

invokes

to

symbolise

her

plight.

What

seems

at

first

|~~~~~~~~~~~~~r

sm

,

NO

~~~~~~~~~~~~~..

|

l~~~~~~~

~~~~~

~

...1

:..

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~1*S

Frida

Kahlo

and

Dr

Farill

in

1952

sight

a

spontaneous

outpouring

of

raw

emotion

is,

in

fact,

distanced

and

mediated

through

culture.

Rivera,

who

believed

passionately

in

the

political

mission

of

art,

insisted

that

her

painting

was

"individual-collec-

tive."2

Her

body

is

a

site

where

wider

political

concerns

intersect:

the

issue

of

Mexican

nationalism

versus

dependence

on

a

technologically

and

medically

superior

North

America

informs

the

juxtaposition

of

motifs

drawn

from

these

disparate

sources.

In

pictures

such

as

Frida

and

the

Miscamage

medical

anatomy

converses

on

an

equal

plane

with

myth

and

popular

Mexican

beliefs

about

the

body

and

illness;

each

is

affirmed

as

a

legitimate

source

of

meaning.

Kahlo

used

medical

imagery

to

record

her

own

singular

history.

The

paradox

is

that

in

doing

so

she

exploded

preconceptions

of

what

is

permissible

in

high

art

and

proclaimed

a

message

"individual-collective"

in

its

many

resonances.

1

Herrera

H.

Frida.

A

biography

of

Frida

Kahlo.

New

York:

Harper

and

Row,

1983:50;142;148;157;231.

2

Rivera

D.

Textos

de

arte.

Mexico

City,

1986:

282-93.

3

Hall

RC,

Beresford

TP,

Quinones

JE.

Grief

following

spontaneous

abortion.

Psychiatr

Clin

N

Am

1987;3:405-20.

4

Warner

M.

Alone

of

all

her

sex.

The

myth

and

the

cult

of

the

Virgin

Mary.

London:

Weidenfeld

and

Nicolson,

1976:206-23.

5

Anonymous.

The

Diego

Rivera

Frescoes.

A

guide

to

the

murals

of

the

garden

court.

Detroit:

Detroit

Institute

of

Arts,

1933.

6

Chavez

I.

Diego

Rivera:

sus

frescoes

en

el

instituto

nacional

de

cardiologia.

Mexico

City:

Sociedad

Mexicana

de

Cardiologia,

1946.

7

Franco

J.

Plotting

woman.

Gender

and

representation

in

Mexico.

London:

Verso,

1989.

8

Breton

A.

Surrealism

and

painting.

London:

Macdonald,

1972:141-4.

Meuse

nr

Dinat

by

John

Horder

BMJ

VOLUME

299

23-30

DECEMBER

1989

1587