U

.

S

.

GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE

WASHINGTON

:

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office

Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800

Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001

85–600 PDF

2014

RISE OF INNOVATIVE BUSINESS MODELS:

CONTENT DELIVERY METHODS

IN THE DIGITAL AGE

HEARING

BEFORE THE

SUBCOMMITTEE ON

COURTS, INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY,

AND THE INTERNET

OF THE

COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY

HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES

ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS

FIRST SESSION

NOVEMBER 19, 2013

Serial No. 113–74

Printed for the use of the Committee on the Judiciary

(

Available via the World Wide Web: http://judiciary.house.gov

(II)

COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY

BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia, Chairman

F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, J

R

.,

Wisconsin

HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina

LAMAR SMITH, Texas

STEVE CHABOT, Ohio

SPENCER BACHUS, Alabama

DARRELL E. ISSA, California

J. RANDY FORBES, Virginia

STEVE KING, Iowa

TRENT FRANKS, Arizona

LOUIE GOHMERT, Texas

JIM JORDAN, Ohio

TED POE, Texas

JASON CHAFFETZ, Utah

TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania

TREY GOWDY, South Carolina

MARK AMODEI, Nevada

RAU

´

L LABRADOR, Idaho

BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas

GEORGE HOLDING, North Carolina

DOUG COLLINS, Georgia

RON DeSANTIS, Florida

JASON T. SMITH, Missouri

JOHN CONYERS, J

R

., Michigan

JERROLD NADLER, New York

ROBERT C. ‘‘BOBBY’’ SCOTT, Virginia

MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina

ZOE LOFGREN, California

SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas

STEVE COHEN, Tennessee

HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, J

R

.,

Georgia

PEDRO R. PIERLUISI, Puerto Rico

JUDY CHU, California

TED DEUTCH, Florida

LUIS V. GUTIERREZ, Illinois

KAREN BASS, California

CEDRIC RICHMOND, Louisiana

SUZAN DelBENE, Washington

JOE GARCIA, Florida

HAKEEM JEFFRIES, New York

S

HELLEY

H

USBAND

, Chief of Staff & General Counsel

P

ERRY

A

PELBAUM

, Minority Staff Director & Chief Counsel

S

UBCOMMITTEE ON

C

OURTS

, I

NTELLECTUAL

P

ROPERTY

,

AND THE

I

NTERNET

HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina, Chairman

TOM MARINO, Pennsylvania, Vice-Chairman

F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, J

R

.,

Wisconsin

LAMAR SMITH, Texas

STEVE CHABOT, Ohio

DARRELL E. ISSA, California

TED POE, Texas

JASON CHAFFETZ, Utah

MARK AMODEI, Nevada

BLAKE FARENTHOLD, Texas

GEORGE HOLDING, North Carolina

DOUG COLLINS, Georgia

RON DeSANTIS, Florida

JASON T. SMITH, Missouri

MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina

JOHN CONYERS, J

R

., Michigan

HENRY C. ‘‘HANK’’ JOHNSON, J

R

.,

Georgia

JUDY CHU, California

TED DEUTCH, Florida

KAREN BASS, California

CEDRIC RICHMOND, Louisiana

SUZAN DelBENE, Washington

HAKEEM JEFFRIES, New York

JERROLD NADLER, New York

ZOE LOFGREN, California

SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas

J

OE

K

EELEY

, Chief Counsel

S

TEPHANIE

M

OORE

, Minority Counsel

(III)

C O N T E N T S

NOVEMBER 19, 2013

Page

OPENING STATEMENT

The Honorable Howard Coble, a Representative in Congress from the State

of North Carolina, and Chairman, Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual

Property, and the Internet .................................................................................. 1

WITNESSES

Paul Misener, Vice President, Global Public Policy, Amazon.com

Oral Testimony ..................................................................................................... 3

Prepared Statement ............................................................................................. 6

John McCoskey, Executive Vice President and Chief Technology Officer, Mo-

tion Picture Association of America

Oral Testimony ..................................................................................................... 13

Prepared Statement ............................................................................................. 15

Sebastian Holst, Executive Vice President and Chief Strategy Officer, Pre-

Emptive Solutions

Oral Testimony ..................................................................................................... 21

Prepared Statement ............................................................................................. 23

David Sohn, General Counsel and Director, Project on Copyright and Tech-

nology, Center for Democracy and Technology

Oral Testimony ..................................................................................................... 33

Prepared Statement ............................................................................................. 35

LETTERS, STATEMENTS, ETC., SUBMITTED FOR THE HEARING

Material submitted by the Honorable Judy Chu, a Representative in Congress

from the State of California, and Member, Subcommittee on Courts, Intel-

lectual Property, and the Internet ...................................................................... 45

(1)

RISE OF INNOVATIVE BUSINESS MODELS:

CONTENT DELIVERY METHODS

IN THE DIGITAL AGE

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 19, 2013

H

OUSE OF

R

EPRESENTATIVES

S

UBCOMMITTEE ON

C

OURTS

, I

NTELLECTUAL

P

ROPERTY

,

AND THE

I

NTERNET

C

OMMITTEE ON THE

J

UDICIARY

Washington, DC.

The Subcommittee met, pursuant to call, at 1:31 p.m., in room

2141, Rayburn Office Building, the Honorable Howard Coble

(Chairman of the Subcommittee) presiding.

Present: Representatives Coble, Goodlatte, Conyers, Watt,

Marino, Smith of Texas, Chabot, Issa, Poe, Chaffetz, Farenthold,

Holding, Collins, DeSantis, Smith of Missouri, Chu, Deutch, Bass,

Richmond, DelBene, Jeffries, and Lofgren.

Staff present: (Majority) Joe Keeley, Chief Counsel; Olivia, Lee,

Clerk; and (Minority) Stephanie Moore, Minority Counsel.

Mr. C

OBLE

. Good afternoon ladies and gentlemen. Welcome to

the hearing.

The Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property, and the

Internet will come to order.

Without objection the Chair is authorized to declare recesses of

the Subcommittee at any time.

We welcome all our witnesses today and those in the audience

as well.

This afternoon we will hear from a group of a—from a panel of

distinguished representatives, who are involved with some of the

leading copyright policy in technology issues of our time. The bene-

fits to America’s economy, brought about by our Nation’s copyright

laws are the envy of the world. Our economy is stronger and gen-

erates more original creativity than in any other country.

Although probably true that the way I listened to music way

back yonder, when I was growing up, is certainly not the way

young people listen today. I can say with certainty that America’s

a better place when the creativity of our Nation’s artists can be en-

joyed by our society. And now that everyone seems to own a collec-

tion of handheld electronic devices, Americans have even more ac-

cess to more content than any time in history.

2

*The information referred to was not available at the time this hearing record was printed.

One reason why this creativity exists is that our Nation’s intel-

lectual property laws are designed to reward those who invest their

time and resources into the developing of original works of intellec-

tual property. This intellectual property is not just embodied in a

song, a book or a movie, but in the very device used to enjoy it.

Our Nation is also not hesitant when it comes to embracing new

ways of doing business. For example it is safe to say that the Inter-

net has simultaneously destroyed old business models while devel-

oping new ones.

One of our witnesses works for a company that has demonstrated

how the Internet has created new business models. Built originally

around the old-line distribution of books, Amazon has grown in less

than two decades into a diversified company that recently an-

nounced a partnership with the U.S. Postal Service to expand home

deliveries into Sunday in some cities. In this case, innovation is

changing business models and driving government policy to help

meet consumers’ demand.

I look forward from all the witnesses this afternoon about the

rise of innovative business models in the digital age and how con-

sumer expectations are changing as a result.

Good to have you all with us.

I now recognize the Ranking Member, the gentleman from North

Carolina, Mr. Watt, for his statement.

Mr. W

ATT

. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

And I am going to pass on the opportunity to make an opening

statement because I really want to give the witnesses to testify.

And I understand we are going to have a vote and I have got to

be somewhere.

So, I—in the interest of time to get to the witnesses and hear

their testimony, I think I will submit my statement for the record

and yield back.*

Mr. C

OBLE

. I thank the gentleman. And, as you have—Mr. Watt

pointed out, there will be a vote, I am told, forthcoming. So, we will

proceed accordingly.

If you all will bear with me just for a minute.

Let me, first of all, just ask you—each of you to stand, if you will,

and we will. I will swear you in.

[Witnesses sworn.]

Mr. C

OBLE

. Our first witness today is Mr. Paul Misener, Vice

President for Global Policy, Public Policy at Amazon.com. For the

past 14 years Mr. Misener has been responsible for formulating

and representing the company’s public policy position worldwide.

Mr. Misener received his J.D. from the George Mason University

School of Law and a B.S. in electrical engineering from Princeton

University.

Our second witness today, Mr. John McCoskey, Executive Vice

President and Chief Technology Officer at the Motion Picture Asso-

ciation of America. Prior to the MPAA, Mr. McCoskey was a—has

served as Chief Technology Officer at PBS and Vice President of

Product Development of Comcast Corporation. He earned his M.S.

degree in computer science and technology management from

3

Johns Hopkins University and his B.S. in electrical engineering

from the Bucknell University.

Our third witness today, Mr. Sebastian Holst, Executive Vice

President and Chief Strategy Officer at PreEmptive Solutions. In

his position, Mr. Holst is responsible for product strategy and man-

agement aiming to protect software against reverse engineering

and piracy. Mr. Holst is also a cofounder of The Mobile Yogi mobile

app focusing on yoga. He received his degree from Vassar College

and Harvard Business School.

Our fourth and final witness is Mr. David Sohn, General Counsel

and Director for the Center on Democracy and Technology Project

on Copyright and Technology. This project seeks to promote reason-

able pro-consumer approaches to copyright and related policy

issues. Prior to joining CDT in 2005, Mr. Sohn worked as Com-

merce Counsel for Senator Rob Wadden and practiced law at Wil-

bur, Cutler & Pickering. Mr. Sohn received his J.D. from the Stan-

ford School of Law and his B.S. from Albers College.

And I think I heard a bell, so I think it might——

Why don’t we start with our first witness and get the—and then

with the bell I will go vote and we will return imminently.

If you gentlemen—we would like for you to confine your state-

ments, if possible, within the 5-minute time range. And there is a

model on your desk. When that red light appears, your time is run-

ning out. You won’t be severely punished, however, but if you could

stay within that time limit I would appreciate it.

TESTIMONY OF PAUL MISENER, VICE PRESIDENT,

GLOBAL PUBLIC POLICY, AMAZON.COM

Mr. M

ISENER

. I appreciate that, Mr. Chairman.

Mr. C

OBLE

. Yes, sir.

Mr. M

ISENER

. Thank you.

My name is Paul Misener and I am Amazon’s Vice President for

Global Public Policy.

Thank you and Mr. Watt for inviting me to testify here today

about the digital content delivery.

Mr. Chairman, Amazon’s mission is to be earth’s most customer-

centric company where people can find and discover anything they

may want to buy online. In furtherance of that mission, we sell mil-

lions of different products in a wide variety of categories. But,

Amazon was born as a media content delivery country—company

with the provision of content to our customers and it remains a

very important part of our business today.

When Amazon began selling online, in 1995, the content we sold

was limited to the text, pictures and other graphics contained in

physical books. Three years later, in 1998, we began to sell music

and video content, also delivered on physical media, primarily

audio compact disks and VHS videotapes.

When I began working for Amazon 14 years ago, our Web site

had a customer support help page entitled, ‘‘Just what is a DVD?’’

That described the then new digital video disk technology. It in-

cluded observations like, quote, ‘‘VHS video tapes are far too en-

trenched in the market to disappear any time soon,’’ and, quote,

‘‘don’t worry you won’t have to trash your VCR, if you don’t want

to.’’ Now, as antiquated as these observations seem to us today, the

4

reality then and the reality now is that Amazon seeks to provide

our customers the greatest selection of content using the best, most

convenient technologies.

By the end of 2007, however, we had introduced digital download

services for books, music and video. And now, when we speak of

digital delivery, we speak primarily of digital content delivered

electronically via the Internet. And so, our digital delivery business

today is a natural continuation of origins as a place where cus-

tomers can find and discover what they want to buy online.

Amazon Instant Video is a digital video streaming and download

service that offers more than 150,000 titles. For digital music, the

Amazon MP3 store currently has a growing catalog of more than

24 million songs in the United States. The Kindle digital bookstore

opened 6 years ago this month and has grown to millions of books,

newspapers and magazines. We now sell more kindle books than

print books. And, remarkably, Kindle owners read four times as

many books as they do prior to owning a Kindle.

Mr. Chairman, in addition to digital content obtained from tradi-

tional publishers, Amazon makes it easy for creators to self-publish

their work. For example, the Amazon subsidiary CreateSpace pro-

vides digital content delivery of video via Amazon Instant Video.

Similarly, authors may use Kindle Direct Publishing to publish

books independently on the Kindle store. Amazon Studios is a new

way to encourage the development and distribution of digital video

content. As you may have seen in Friday’s Washington Post, Ama-

zon Studios has introduced its first comedy series, Alpha House.

Of course, Mr. Chairman, digital delivery of content to consumers

requires some physical infrastructure and electronic devices. You

probably have heard of cloud computing. And, as you may know,

Amazon has a cloud computing business called the Amazon Web

Services or AWS. Amazon Cloud Drive, which is built on AWS, lets

customers manage and store music, videos, documents, and pic-

tures through the Internet. In addition, the Amazon Cloud Player

enables customers to securely store their personal music in the

cloud and play it on a wide variety of devices including Kindle Fire.

AWS helps enterprise customers with various data storage and

computation needs. It also has partnered with Netflix for the deliv-

ery of digital content.

Digital content can be accessed and played through a wide vari-

ety of devices including a fabulous little box from Roku and avail-

able at Amazon that allows me to watch and hear Amazon instant

video, as well as Netflix, Hulu and Pandora, directly on my family

room TV. And you can read you Kindle books on a large number

of devices and platforms. Importantly, customer expectations today

are not only that an individual customer should be able to enjoy

digital content on a single device of her choice, but also that she

should be able to enjoy the same content across multiple devices.

One other, newly available place and time for enjoying digital

content deserves mention. After working for years with the airline

industry and others, Amazon is proud to have played a key role in

the Federal Aviation Administration’s decision just a few weeks

ago to allow consumers to use their electronics, like Kindle, during

airplane takeoff and landing.

5

In conclusion, Mr. Chairman, consumers are enjoying the benefit

of innovative digital content delivery. And Amazon looks forward to

working with the Committee to preserve those benefits in that in-

novation.

Thank you again for the opportunity to testify. And I look for-

ward to your questions.

[The prepared statement of Mr. Misener follows:]

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

Mr. C

OBLE

. Thank you, Mr. Misener.

Mr. McCoskey, we are going to try to get you in before we go

vote. So, if you would proceed for 5 minutes.

TESTIMONY OF JOHN McCOSKEY, EXECUTIVE VICE PRESI-

DENT AND CHIEF TECHNOLOGY OFFICER, MOTION PICTURE

ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA

Mr. M

C

C

OSKEY

. All right. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

Chairman Coble, Ranking Member Watt and Members of the

Subcommittee, my name is John McCoskey and I am Executive

Vice President and Chief Technology Officer for the Motion Picture

Association of America. Thank you for the opportunity to testify on

behalf of the MPAA and its member companies. You have my writ-

ten testimony, I would like to go through some of the highlights of

that in my spoken words.

So, in the United States and throughout the world, an explosion

of innovation is occurring, irrevocably changing much of our daily

lives. The majority of consumers will experience this revolution in

the way they consume the content that they love: the films, tele-

vision series, and other video content they watch; the music they

listen to; and, the books they read.

In the media and entertainment industry, digital technology ad-

vances are affecting everything from glass to glass, that is, every

element between the camera lens and the screen where consumers

experience our content. This is also a time of unprecedented change

in consumer behavior. There are now more mobile devices than

people in the United States, and smartphones and tablets have out-

paced sales of desktop and laptop computers combined.

As the primary advocate throughout the world for American film,

television and home video industries, MPAA and our member com-

panies are committed to promoting a climate that provides audi-

ences with as many options as possible for experiencing the great

video entertainment our country produces.

Nearly 42 million homes in the United States now have Internet-

connected media devices including game consoles, smart TVs and

online set-top boxes. And more than 90 legitimate online services

are already enabling those homes to download or stream movies

and TV shows, and that number continues to grow. MPAA’s

wheretowatch.org Web site offers a one-stop shop for finding legal

content to Americans.

And Americans are visiting these services at an incredible and

growing rate. Last year alone, U.S. audiences consumed nearly 3.5

billion hours of movies online. Our member companies have em-

braced this movement of portability, flexibility and ease of access

for viewers.

And one way they have done so is through UltraViolet, a free

digital storage locker that allows a consumer, after purchasing Ul-

traViolet media such as BlueRay, DVD or electronic purchase over

the Internet, to then access that content on any UltraViolet-com-

patible device registered to them. Consumers have the option to ei-

ther seamlessly stream the content or download it for later viewing

without a broadband connection. Consumers can choose from a

wide number of UltraViolet-enabled services like Flixster, Wal-

mart’s Vudu, Best Buy’s Cinema Now, and so forth.

14

Our member companies, along with other in the Digital Enter-

tainment Content Ecosystem consortium of more than 60 studios,

retail stores, and technology firms, created UltraViolet to further

enable consumers to watch what they want, when they want,

where they want. And because UltraViolet is powered by such a di-

verse consortium of innovative companies, consumers are not

locked to one portal and shift from one service to another as each

continues to innovate. UltraViolet also enables sharing of content

among up to five connected accounts and 12 devices. And more

than 13 million accounts have registered for UltraViolet to date.

The overwhelming success of these legal services and distribution

models in the bridging digital marketplace is a testament to the

success of the U.S. copyright regime, which promotes investment in

both creativity and delivery of content. Recognizing creators’ prop-

erty interest in their creations encourages them to create even

more innovative content. And this in turn spurns investment in ap-

plications, services, devices, and other technologies for viewing that

content.

The Copyright Act enables and encourages entrepreneurs to in-

novate and creates a competitive marketplace for these products

and services. This is reflected in companies like Netflix, Hulu and

Amazon, whose online streaming services began as distribution

outlets for content created by others, but now also drive develop-

ment of new original programming.

This is a transformative time for content creators and distribu-

tors of types, but especially for those working in the American film

and television industry. Our industry supports nearly 2 million jobs

in the United States. It is responsible for 108,000 businesses across

all 50 States, and 85 percent of those employ fewer than 10 people.

In 2011, the industry supported $104 billion in wages, $16.7 billion

in taxes, and a $12.2 billion trade surplus.

And, as the marketplace continues to evolve in the digital age,

we will continue embracing these innovations and the plethora of

legitimate services for delivering content to consumers when they

want, how they want, and on the platforms they want.

Mr. Chairman, Ranking Member, Members of the Subcommittee,

I thank you again on behalf of the MPAA and our member compa-

nies for the opportunity to testify today. And we look forward to

working with you, in the days, months and years ahead, to ensure

that this revolution in content creation and delivery continues to

be embraced by all members of the digital economy, and that cre-

ators and makers continue to be encouraged to experiment and in-

novative.

And I am happy to answer any questions you may have.

[The prepared statement of Mr. McCoskey follows:]

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

Mr. C

OBLE

. Thank you, Mr. McCoskey.

You all stand easy and we will return imminently.

[Recess.]

Mr. C

OBLE

. We will resume the hearing.

I owe you an apology, I told you I would be back imminently, but

our return is not so imminent. But, I had no control over that.

Good to have you, Mr. Holst. If you will be—if you will kick us

off on the second event.

TESTIMONY OF SEBASTIAN HOLST, EXECUTIVE VICE PRESI-

DENT AND CHIEF STRATEGY OFFICER, PREEMPTIVE SOLU-

TIONS

Mr. H

OLST

. Okay.

Chairman Coble, Member Watt, distinguished Members of the

Committee, my name is Sebastian Holst and I appear today wear-

ing many hats.

I am the Chief Strategy Officer at PreEmptive Solutions. Our

software products are used by tens of thousands of developers to

secure and to monitor their apps, increasing app quality, improving

user experience and securing intellectual property. I am an app

creator who, along with my wife Dawn, have published a family of

yoga apps for consumers and small businesses. I am the founder

of a cyber-security and brand-monitoring service that provides

threat analysis for public and private institutions. And I am also

here representing the Association of Competitive Technology, ACT,

the world’s leading app association representing over 5,000 small

and medium-sized tech companies.

Today I am pleased to have the opportunity to share a software

developer’s perspective as the Committee considers the trans-

formative impact of emerging content delivery methods in the dig-

ital age.

To truly appreciate the magnitude of innovation occurring

around us it helps to consider this one fact: no technology has been

adopted faster by consumers than the smartphone ever; not the

car, the microwave, not electricity, or even the Internet. And just

what makes these smartphones so smart? Quite simply it is the

apps they run. In just 6 years, smartphone apps have grown into

a $68 billion industry and are expected to top $140 billion by 2016.

The industry’s growth is also a job creation machine. Over

750,000 jobs in the U.S., and over 800,000 in Europe have been cre-

ated through this new app economy. And with the median salary

for a software developer topping $92,000, these are great jobs to

have.

The rise of the mobile app economy has also significantly

changed how apps are developed and marketed. Before the

smartphone paradigm shift, developers faced enormous obstacles

reaching consumers. We either sold packaged software in a store

involving huge overhead or over the Internet where getting noticed

was hard and managing payments and financial data could be ex-

ceptionally burdensome and even risky. Taken together these chal-

lenges posed significant barriers to entry and stunted growth.

And then came the smartphone app store: a simple, centralized

one-stop shop for the consumer. In an app store a developer sells

software directly to consumers. And, for a reasonable percentage of

22

the topline, app stores handle financial transactions, product place-

ment and ensure a safe, standardized shopping experience. With

the app stores, consumers find that what—with app stores con-

sumers find the apps they are looking for and developers can do

what they do best—build great apps.

Of course app stores are not all created equal. How are stores

curated? Meaning how apps are vetted for quality, truth in adver-

tising, and even for how they use underlying hardware and net-

work services can make the difference between a safe and satis-

fying shopping experience or one where malware, piracy and pri-

vacy risks cannot be safely ignored. Some of the most widely

used—surprisingly, non-curated stores are popular. Some of the

more widely used smartphones cater to this category. Yet, iron-

ically, while usage is high in many of these ‘‘wild west’’ market-

places, curated stores still deliver more than 75 percent of the reve-

nues earned by app makers.

Another byproduct of app store popularity is that they are start-

ing to exhibit some of the old problems. Specifically, with over a

million apps available in app stores, discoverability, the ability to

stand out in a crowd, is once again becoming difficult. But now de-

velopers have a better answer to this problem. Reputation, quality

and a focus on users, experiences and their preferences are critical

to standing out in a crowded marketplace.

One key innovation here has been the rise of application ana-

lytics. Application analytics provide visibility into user trends, end

user behaviors and all manner of quality. Application analytics

technology, like PreEmptive’s, has emerged as one of the key com-

petitive weapons successful developers are using to separate them-

selves from the rest of the pack.

Now some people will tell you that technology changes every-

thing. But, when it comes to basic notions of right and wrong, fair-

ness and innovation, nothing could be further from the truth.

Thanks to technology, the potential for growth and innovation has

never been higher. But that is why the need to stay grounded in

our basic beliefs has never been greater. I am confident that a re-

view of the copyright system will be successful, as long as we re-

main true to these principles that have guided our judgment on the

universal themes of intellectual property, fostering innovation and

fairness.

Thank you for the opportunity to speak here today. And I look

forward to answering any questions you may have.

[The prepared statement of Mr. Holst follows:]

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

Mr. C

OBLE

. Thank you, Mr. Holst, I appreciate it.

Mr. Shaw—Sohn? Sir, am I pronouncing your name correctly?

Mr. S

OHN

. Sohn, yes.

Mr. C

OBLE

. Sohn.

TESTIMONY OF DAVID SOHN, GENERAL COUNSEL AND DIREC-

TOR, PROJECT ON COPYRIGHT AND TECHNOLOGY, CENTER

FOR DEMOCRACY AND TECHNOLOGY

Mr. S

OHN

. Chairman Coble, Ranking Member Watt, Members of

the Subcommittee, on behalf of the Center for Democracy and

Technology, thank you very much for the opportunity to participate

in today’s hearing.

My statement today will focus on how consumer expectations and

behaviors are evolving in today’s marketplace for copyrighted

works. What I would like to do is highlight a few trends and then

offer some thoughts on what those trends mean for congressional

action on copyright.

So first, consumers increasingly expect the ability to get what

they want when they want it. The Internet—Internet delivery—

gives them convenience and immediacy. It also frees them from the

limits of what is on TV at a particular time or what physical inven-

tory will fit on the shelves at their local store. So, increasingly con-

sumers expect to have comprehensive selection, to be able to pick

precise content to suit their individual tastes, and to enjoy that

content at times of their own choosing. In short, it is becoming

more of an ‘‘on demand’’ world.

The second trend I would point to is the rising importance of mo-

bility and portability. Rather than being tethered to a particular

place or a particular device, consumers increasingly want seamless

access to their content on a mobile basis and across multiple de-

vices.

Third, and in some ways most significant, there has been a mas-

sive increase in creative activity by the public. Consumers today

are not just passive recipients of creative material. They create and

interact with copyrighted works as never before. They blog, they

distribute photos and videos on social networks, they use excerpts

of other works to create their own remixes or commentary. In sum,

digital technology really blurs the lines between creators and con-

sumers, enabling greater public involvement and interaction with

creative works than ever before.

The good news is that distribution models and technologies are

rapidly evolving in ways that both cater to and fuel these trends.

There are new business models, such as streaming services based

on subscriptions or advertising. Social networks play prominent

new roles in empowering individual creators and artists to dis-

tribute works either with a commercial purpose or without a com-

mercial purpose. Creative Commons offers a more diverse set of li-

censing strategies. New classes of devices, like tablets and e-read-

ers, create new options for consumers.

In lots and lots of ways, the market is working. But, inevitably,

it is also a work in progress. Responding to these kind of evolving

demands is not a onetime challenge. It requires ongoing experimen-

tation and innovation.

34

So, with these trends in mind, I would like to offer several

thoughts for Congress’s review of copyright law.

First, Congress should focus on ensuring that the legal regime

encourages continued innovation to give consumers what they

want. Now, to be clear, consumers are not legally entitled to on-

demand access to everything they want any more than they are en-

titled to get everything they want for free. But, everyone is better

off if the market can develop new offerings that recognize what

consumers want and find ways to provide it lawfully. Because

whenever legal services don’t do a good job of catering to market

demands, unlawful sources are out there waiting to fill the gaps.

In the end, the best and most effective defense against widespread

infringement is a robust and evolving content marketplace.

To promote that goal, Congress should start by taking care not

to undermine those elements of the current regime that encourage

marketplace and technology innovation. My written statement

highlights three in particular: the safe harbor, set forth in section

512 of the DMCA; the ‘‘Sony doctrine’’ concerning products capable

of substantial non-infringing use; and the flexible and hugely im-

portant doctrine of fair use.

Congress should also consider reforming the Copyright Act’s stat-

utory damages provisions. The current regime acts as a massive

risk multiplier for any company or individual trying to navigate

any unsettled area of copyright law. It therefore discourages inno-

vation. And it undermines the trend toward public creativity and

interaction by threatening individuals with disproportionate sanc-

tions for any mistake they might make.

Another step Congress should consider is providing greater legal

certainty for personal noncommercial uses, such as moving content

among devices for one’s own personal use.

And finally, Congress should make simplifying the Copyright Act

one of the goals of any reform effort. As more and more of the pub-

lic creates, remixes and otherwise interacts with copyrighted mate-

rial, copyright needs to be easier for the public to navigate.

Once again, thanks for the opportunity to participate today. We

look forward to working with the Subcommittee as its work on

copyright continues.

[The prepared statement of Mr. Sohn follows:]

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

Mr. C

OBLE

. Thank you, Mr. Sohn.

I appreciate the testimony from each of the witness. And I appre-

ciate those in the audience. Obviously, your presence here rep-

resents more than a casual interest in the subject at hand.

Gentlemen, we try to comply with the 5-minute rule as well. So,

if you all could keep your responses terse, we would appreciate

that.

Mr. Misener, as your company has grown, what challenges, from

a copyright perspective, have you faced?

Mr. M

ISENER

. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

There are three that I have outlined in my written statement

and I can briefly summarize them here.

One is with respect to music licensing. The process is very dif-

ficult and cumbersome. If the policy goal is to get as much copy-

righted works available out to paying consumers, this—the current

process for licensing is in need of reform.

Second, as Mr. Sohn has just described, the statutory damages

provisions currently in law are—can produce some exorbitant pen-

alties and create high risks for—especially for large libraries of

copyrighted works. And it seems to me that those damages might

be limited in some way that recognizes good-faith efforts to not in-

fringe or to use fair use or when a defendant faces a novel question

of law.

And lastly, all of this innovation depends heavily on maintaining

an open and nondiscriminatory Internet.

Mr. C

OBLE

. Thank you, Sir.

Mr. Holst, with extremely low or even no-cost price points for

apps, what justifications do you hear from pirates who cannot

claim that prices are too high as a justification for their theft?

Mr. H

OLST

. The fact that an application is either free or low-cost

doesn’t really represent either the work that has gone into it or the

strategy—the total market strategy. From a risk point of view,

pirating and counterfeiting of these free apps essentially is equiva-

lent of being able to deliver counterfeit car parts or pharma-

ceuticals. So, very often, branded, recognized software is remar-

keted and redistributed with certainly nefarious motivations.

Mr. C

OBLE

. I thank you, sir.

Mr. McCoskey, for you and Mr. Sohn. What are the most effec-

tive ways, in your view, to convince consumers to use legitimate al-

ternatives to online piracy?

Mr. M

C

C

OSKEY

. One of the things we try to do is actually make

sure that consumers know that there are legitimate sources of con-

tent. And that is one of our challenges in this ecosystem, we got

all these different players, actually being able to get those legal ac-

cess to content in front of consumers, when there is a mix of access

to illegal content. So, a big part for us is, not only creating paths

and distribution mechanisms where we do distribute this content

legally, but also getting consumers ways where they can find that

content.

Mr. C

OBLE

. Thank you, sir.

Mr. Sohn?

Mr. S

OHN

. I think it is largely a question of having lots of choice

and lots of innovation in the marketplace. It is going to require ex-

perimentation to see what forms of services consumers are most in-

44

terested in. But, I think the early success of iTunes, which was

kind of a pioneer in digital music, showed that when services give

consumers a broad selection at an attractive price point and a serv-

ice that works well, consumers are interested in using the lawful

marketplace.

Mr. C

OBLE

. Thank you, sir.

The Chair is recognizing the Ranking Member for the full Com-

mittee, the distinguished gentleman from Michigan, Mr. Conyers.

Mr. C

ONYERS

. I would yield to the gentlelady, Ms. Chu, if it is

all right with her and you.

Mr. C

OBLE

. It is fine with me, if it is okay with her.

The gentlelady from California, Ms. Chu?

Ms. C

HU

. Thank you so much, Mr. Chair.

Well, first I would like to submit for the record three items. First

is testimony from Sandra Aistars, Executive Director of the Copy-

right Alliance. Ms. Aistars testimony illustrates that it is not just

major motion picture studios and TV show creators who are invent-

ing—investing and supporting new distribution models, but an en-

tire alliance of creators, from church music publishers to remixers

to medical illustrators to illustrators, who are engaging in expand-

ing in all kinds of digital delivery models. Which demonstrates that

copyright owners of all mediums and backgrounds work actively to

ensure that their work is easily accessible and can be enjoyed as

widely as possible.

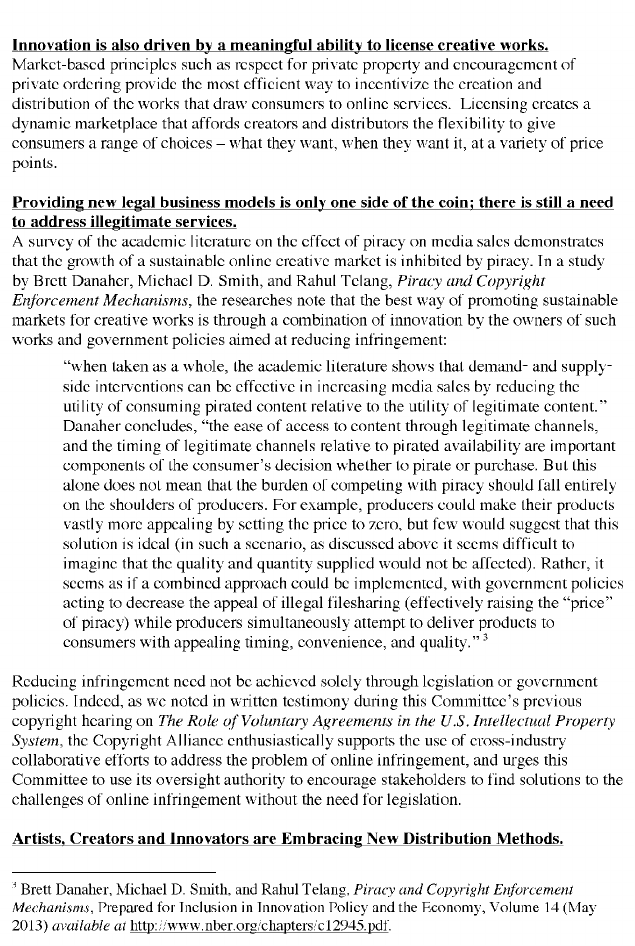

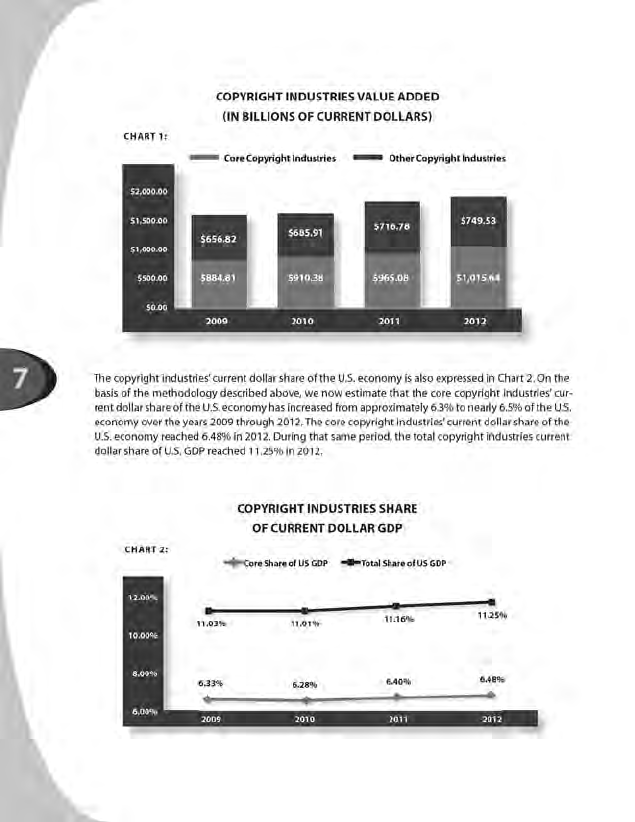

And then the second is a study that was released today from the

Intellectual Property Alliance, which solidifies the fact that U.S.

copyright industries, for the first time, contributed over $1 trillion

to the U.S. economy accounting for nearly 6.5 percent of GDP. I

mean, obviously, with this report, we know that creative rights are

driving economic growth and innovation.

And thirdly, I am submitting a Copyright Alliance article about

this intellectual property report.

Mr. C

OBLE

. Without objection, they will be received——

Ms. C

HU

. Thank you.

Mr. C

OBLE

[continuing]. And made a part of the record.

[The information referred to follows:]

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

ATTACHMENT

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

Ms. C

HU

. Thank you so much.

Well, my first question is for Mr. McCoskey. One of the consumer

complaints out there is that content creators do not do enough to

make their works available and accessible. But, now we have more

than 90 legitimate streaming services offering movies and TV

shows in the U.S., such as Amazon, Netflix and UltraViolet, just

to name a few. There is truly a service for every type of content

consumer out there, whether it is for your smartphone or tablet so

that you can watch whatever, whenever you want.

And although Americans legally consumed about 3.5 billion

hours of movies online in 2012, a recent study by NetNames

showed that 24 percent of total Internet bandwidth worldwide in-

volves traffic on infringing sites and services. Why do you think

that is the case, considering the rise of all these innovative ways

for consumers to watch content legally in their digital space? And

what more can the key players in the Internet ecosystem do about

this?

Mr. M

C

C

OSKEY

. Well, as you have pointed out, this is a problem

that continues to evolve. And so, the fact that now there are 90

places that you can find legitimate in the—content in the country

is important. And that number is growing. But the reality is that

piracy still is a big issue for the industry. This is a multi-stake-

holder ecosystem. And we think that voluntary measures of getting

all the players together in the ecosystem are working toward solv-

ing that issue. So, for example, we have a thing we call the Copy-

right Alerting System that helps identify when consumers are ac-

cessing infringed content. And we use that as a mechanism along

with other players in the ecosystem. But, it is a constant issue and

it is evolving and we think the best way to deal with that is to con-

tinue talking and working with every player in the ecosystem.

Ms. C

HU

. Okay.

Mr. Misener, I want to thank you for testifying on behalf of Ama-

zon today. Not only am I a longtime Amazon Prime member, but

a fan—I am also a fan of Prime Instant Video. So, I certainly enjoy

what you’re doing. And it is great to see that your company is now

contributing to the Internet ecosystem with creative works, with

your Alpha House in which you have invested $11 million. But, you

now would be facing unauthorized streaming. And so, I was a bit

curious about your role or your stance on statutory damage, be-

cause now you could be the victim of this piracy. What is—how do

you reconcile that?

Mr. M

ISENER

. Yeah. Thanks, Ms. Chu, very much.

Amazon abhors piracy. We have from our very beginning. Our

very first day was selling legitimate copyrighted works. And so,

every time some pirated material is used or made available a sale

is lost. So we are in a position of always trying to work with con-

tent creators and now with original content creators, like with

Amazon Studios, we want to be in a position to ensure that legiti-

mate copyrighted works are available conveniently at competitive

prices for our customers. And that is going to dissuade piracy in

the first instance.

As far as the statutory damages go, the limitations that we are

suggesting are ones that go to legitimate mistakes, perhaps. When

someone has—makes a good faith effort and perhaps comes up

88

against—they believe they are not infringing or they believe that

they are engaged in fair use in a legitimate way. Or for example,

if they are at a point where there is a novel question of law that

is raised and reached by a court. At that point, that is where the

statutory damages ought to be limited.

Ms. C

HU

. Okay.

Well, I think my time is out so——

Mr. C

OBLE

. The gentlelady’s time is expired.

The distinguished gentleman from Pennsylvania, Mr. Marino?

Mr. M

ARINO

. Thank you, Chairman.

Good afternoon, gentlemen, thank you for being here.

I have been studying search engines for some time now, several

weeks now. I have been studying the types of search engines and

the big search engines that are out there. And one thing that

seems to be a common thread running through the search engines

are: even though we are aware of a pirate Web site, whether it is

telling us that we can give this—send this music free or they

charge us 10 cents for it or movies or any other technology that you

want to get into—they are appearing at the top of Web—of the

search engines as an entity, which one can get into immediately.

Do you understand my question so far?

Okay. No response. You must understand it.

What do we do, what does industry do, what do the search en-

gines do about having these pirate sites pop up at the top of a

search, compared to the legitimate entities that are out there that

are several pages down? Anyone care to venture into this first?

It is like school, I will call on you.

Mr. Misener?

Mr. M

ISENER

. I can defer to my colleagues. [Laughter.]

So, naturally we like it when Amazon shows up first. But, when

it doesn’t——

Mr. M

ARINO

. Very legitimate.

Mr. M

ISENER

[continuing]. There should be a good reason for it.

And so, I—we don’t have a search engine business, per se. We have

a site that is searchable, obviously. But it is a question—it is a dif-

ficult question. We think that the DMCA is out there for address-

ing infringement on particular Web sites, right? There is this notice

and takedown provision for platforms. And we think that is what

strikes the right balance between the interests of the creative com-

munity and the platform operators.

But, as far as Web site searches themselves go, I think maybe

Mr. McCoskey has a stronger view.

Mr. M

ARINO

. Mr. McCoskey? Because I have—last weekend I vis-

ited New York and had the opportunity to visit businesses. And

one of their biggest complaints, in the technology end of things,

was piracy. And I actually took down a couple of rogue sites. But

we know that as soon as that site is taken down, ten others go up.

So, again, to reiterate my question so it is clear I probably didn’t

present it clearly. What do we do about preventing those rogue

sites popping up at the top of the list?

Because how many of us go through page after page to find a le-

gitimate entity? No, we look at the first three or four. And rou-

tinely I am coming up with the first two or three, at least, are

rogue sites. And the reason I know this is because my kids, 18 and

89

14, and I—you saw me come in with my music. And I download

music and listen to it all the time, but they tell me, ‘‘Dad, stay

away from this one and stay away from that one, because a guy

in your position can’t afford to have headlines saying that I am

downloading music and not paying for it.’’ And I have to agree with

them.

So, how do we address this issue? How does—from a technical

standpoint, how does the industry address this? Because I am

not—you notice I am not mentioning any names, and I do not want

to, because I have been in rooms where we have taken down things

by all the big companies.

Mr. M

C

C

OSKEY

. So, I think the—you know, it is a big problem

and it is a dynamic problem, so it does change. I think it is a com-

bination of approaches to this. The most important one, we believe,

is actually having a dialogue between the players and the eco-

system, who are generally not bad actors. The bad actors are the

infringing sites. And working together on algorithm changes.

And an example we have is we did work with one of the big

search players several months ago. They did an algorithm change,

targeted at reducing the problem that you have identified. And, un-

fortunately, the results of—after several months of that change,

where that did not really change the problem much. So, we are

going to go back to the table and work with them on tying to mod-

ify algorithms to the point that we can change that equation. But

it is a problem.

Mr. M

ARINO

. Is—as we were talking and doing this right here on

an iPad and I know that the three that came up are rogue Web

sites. They are at the top. So, I would prefer that the industry take

care of this, we not legislative, but seriously take care of this be-

cause this is one of the biggest complaints I am hearing.

And then I also want to address——

Mr. H

OLST

. Yeah, I——

Mr. M

ARINO

. Go ahead, John.

Mr. H

OLST

. I would say, first, that it—algorithms can address, at

a moment in time, the kinds of issues that you are raising. But,

it is a cat-and-mouse game. So, as soon—you know, people—the

game of trying to gain the search algorithms for both good, you

know, good actors and bad actors, started on the first day of the

search engine. One of the differences though is that, if you are a

bad actor, you will say and do anything because why not, right? So

it is very similar to making false claims, you know, on a product

you might sell in an infomercial. And so, they will play with

metadata. They will play with false endorsements. They will make

up phantom accounts. So they do cheat, you know. So, by—so on

the technical, it is a cat-and-mouse game. It will be—I do not think

you can ever stamp it out——

Mr. M

ARINO

. I see that my time has run out. So, if you could—

if you would like to respond in writing to me. And I would love to

hear from anyone on how we resolve this.

I yield back. Thank you, Chair.

Mr. C

OBLE

. The gentleman’s time is expired.

The distinguished gentleman from Michigan, Mr. Conyers is rec-

ognized.

Mr. C

ONYERS

. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

90

This is a very interesting and very important hearing. But, what

are your opinions about voluntary solutions? Are we relying too

heavily on this? Or is this just a, you know, polite discussion here

that nobody really sees as a serious way to reduce piracy? What

are any of your thoughts about that?

Mr. S

OHN

. Sure, I will weigh in on that. I think voluntary solu-

tions can be a very productive way to try to reduce infringement.

I think there are opportunities. The Copyright Alert System is a

system that is launched between the major ISPs and some of the

major rights holders. And I think that is an example of an effort

that is voluntary. It is aimed primarily at education to make sure

that users understand the difference between infringing behavior

and lawful behavior.

So, I think there is a role for discussion on voluntary measures.

I think there is also—it is important that we be somewhat cautious

in approaching those as well in that the more voluntary measures

aim at punishing or sanctioning particular entities, the more it

starts getting into a role that we normally do through government

or with some kind of due process. And so the balance for voluntary

measures is to figure out where they can be productive without

causing risks of overreaching or abuse or short-circuiting the due

process that we would normally expect.

Mr. C

ONYERS

. Mr. Misener?

Mr. M

ISENER

. Yes, Mr. Conyers. I think it is a great question.

The way we have tried to approach it at Amazon is to make the

legitimate content as easily available and as inexpensively avail-

able as possible. In books, in particular, we have seen a willingness

on customers’ behalf to pay for books. They will pay for them. We

have over a million that are priced at $4.99 or less, 1.7 million

priced at $9.99 or less. And people are happy to pay that if there

is an easy way to do it. And so, from an industry player, like Ama-

zon, our goal is to make it easy to obtain that legitimate content

for pay.

Mr. C

ONYERS

. Mr. McCoskey.

Mr. M

C

C

OSKEY

. So, I think as long as we have a strong support

of the property right of the content, the industry is really working

together on these kinds of issues and it is a very dynamic situation.

You have got all kinds of new distribution paths, new devices for

consumption. But, at this point, I think that voluntary approach

is—letting the industry try to work this out is really what we

would like to see happen.

Mr. H

OLST

. I would say that detecting bad behavior, preventing

it, you know, helping people do the right thing through discovery

and ease of use that is a fluid activity that really has to be able

to be agile and to move quickly. On the other hand, there needs

to be clear guidelines when someone is a bad actor, and that should

not be by consensus. That needs support.

Mr. C

ONYERS

. Well, thanks for the variety of views on that sub-

ject.

Let us turn to app piracy. Do our current legal tools allow us to

effectively address the subject of that piracy at all?

Mr. H

OLST

. I will go first. I will say, I have actually been the

subject of app piracy myself. I have found my content in someone

else’s app actually beating me in the marketplace because they

91

took my paid version and made it free. And, in fact, the response

was quick once I found it, right? So, I think we don’t need more

legislation. We need—I think we have clear recourse. Again, I

think the slippery slope is finding those bad guys quickly and pre-

venting them from reintroducing themselves with a slightly dif-

ferent name, right? But that is—but it is a technical and a commu-

nity issue. I am not sure I need tougher laws.

Mr. C

ONYERS

. Anyone else want to weigh in on this?

Then I yield back the balance of my time.

Mr. C

OBLE

. Thanks. I thank the gentleman.

In order of arrival time, I recognize the gentleman from North

Carolina for the next questioner.

Mr. H

OLDING

. Thank you, Mr. Chairman. I thank the gentleman

from North Carolina.

Mr. McCoskey, the technology obviously changes incredibly

quickly today and is something this Committee grapples with and

has grappled with throughout history. So, some say recent techno-

logical changes demand changes in the copyright law. But, is there

really a problem today that needs fixing? I mean, hasn’t techno-

logical change made it easier to get existing content to viewers?

And, in fact, hasn’t it also made it easier to get new content to

viewers? Isn’t it—the video marketplace thriving, you know, under

the legal regime that we have right now?

Mr. M

C

C

OSKEY

. I think it is doing exactly that. We have this

strong property right and because we have that it is encouraging

companies to innovate, try new things and work with consumers on

what they want. So, I think it is absolutely a good, good program

now.

Mr. H

OLDING

. Mr. Misener, one of your recommendations is for

a streamlined statutory licensing process for music. Would an ac-

cessible and robust ownership database solve most of the problem

of connecting music copyright owners and licenses, without the

need for any statutory license?

Mr. M

ISENER

. Thank you for the question.

I think that there is a need for some sort of centralized informa-

tion source. And I agree that if it were legislated I think it would

be obviously taken more seriously perhaps. But, you are right to

say that the problem is trying to find information on rights holders

and to find the authors and the artists, in order to obtain the li-

cense permission to make that content available to our customers.

And so, it may go a ways to doing that. I also could see just some

reform within the statutory licensing scheme that exists today.

Mr. H

OLDING

. Lastly, do you, Mr. Sohn—what are the ways that

you see, you know, right now that Congress can ensure a robust

competition in the marketplace for digital goods?

Mr. S

OHN

. Well, I think the first things that it can do are take

care to preserve those elements of the legal regime that are suc-

cessfully enabling innovation right now. So, the ones I highlighted

in testimony are fair use, which has been the subject of some im-

portant court decisions recently. Also section 512 in the DMCA,

which provides important safe harbor for innovators. And then,

some of the court-made doctrine, particularly the Sony doctrine

from the 1984 case involving the VCR, where they said that if a

product has a substantial non-infringing use, it is lawful to dis-

92

tribute it even if some users might end up using it for infringe-

ment. So, those are some core principles that have enabled

innovators to develop innovative technologies, innovative services.

And those need to be preserved. I think that is first and foremost.

The second one that I highlight in my testimony is statutory

damages reform, because I think that is one that creates very high

risk for any company that is trying to navigate an uncertain or un-

settled area of the law. And, in this digital age with Internet tech-

nologies, we find that happening in copyright law all the time. You

have new devices with storage capability that are connected to the

Internet, so they can be used to send data. There are lots of ways

that copyright creates questions for new technologies. And so, we

need a statutory damages regime that doesn’t make it too risky to

experiment with that.

Mr. H

OLDING

. Well, you also recognized in your testimony—ei-

ther written or oral, I didn’t hear your oral, but I read your writ-

ten—that streaming has grown in popularity as a primary means

to distribute copyrighted content online and as an alternative to

downloading. So, would you therefore agree that criminal penalties

for illegal streaming should be on par with penalties for illegal dis-

tribution and copyrighting?

Mr. S

OHN

. I think where the streaming activity is of a scale

where it is comparable to a criminal downloader, then yes, there

is no particular reason the law should distinguish between the par-

ticular mode of infringement. I think what it should focus on is the

culpability and the scale of the activity.

Mr. H

OLDING

. Thank you.

Mr. Chairman, I yield back.

Mr. C

OBLE

. I thank the gentleman from North Carolina.

The distinguished lady from California is recognized.

Ms. B

ASS

. Thank you very much, Mr. Chairman.

I want to thank the witnesses for their testimony today.

I think it is great what companies are doing to promote access

to legitimate content, by making it available on so many different

devices, platforms and services. And it is particularly mind bog-

gling to think of how much access consumers have to content.

I have also been impressed with what Internet companies are

doing to promote content partnerships. And the motion picture and

recording industry associations have done great work to help con-

nect content producers with consumers. And I am especially grate-

ful for the ongoing partnerships, since I represent both. In my dis-

trict there is Sony, Fox Studios, Culver Studios, Google is right

next door. There is many other entertainment companies in my dis-

trict.

The one thing I am concerned about is the BitTorrent sites and

I wanted—I know the MPAA won a major copyright victory in its

settlement with IsoHunt. But, just a couple of weeks after the set-

tlement, it is my understanding, that fans of the sites created a du-

plicate site loaded with millions of infringing files. And, I know we

all agree we have to stop this. So, I just had a couple of quick ques-

tions.

I wanted to know what else do you think the industry could do,

besides providing access to content, to help fight BitTorrent sites,

is my question.

93

Mr. M

C

C

OSKEY

. So, as I said earlier, this is a dynamic problem.

And it is a problem that is still significant for the industry. We

think that techniques such as the copyright alerting system, that

basically helps consumers understand when they are accessing in-

fringed content, is a good mechanism for battling this. We think—

again, back to the multi-stakeholder model of finding the good ac-

tors and working together on solving these problems across the

whole Internet ecosystem, is a way to address these. But it is—it

will be a continuing issue and continuing work and it will adapt

and change, you know, as we change our tactics.

Ms. B

ASS

. And do you think that there is a perception that con-

tent owners have been slow to get their products out and that that

is one of the contributing factors?

Mr. M

C

C

OSKEY

. I don’t think so. I mean, when you look at how

many outlets there are for content now and consumers are finding

it in places that they have never been able to find it before legally,

I think the industry has done a really good job of actually recog-

nizing the desires of consumers and trying to meet them.

Ms. B

ASS

. Thank you.

And we are still working on getting Amazon to L.A.

Mr. M

ISENER

. I am sorry. Ms. Bass?

Ms. B

ASS

. I said we are still working on trying to get Amazon

to L.A.—to move to L.A. Well I know, but, you know, they can ex-

pand and they told me about their expansion.

I yield back the balance of my time.

Mr. M

ISENER

. Thank you, Ms. Bass.

Mr. C

OBLE

. I thank the gentlelady.

The gentleman from Utah.

Mr. C

HAFFETZ

. Thank the Chairman.

And I thank you all for being here. It is an interesting world

where—I remember when my son, who is now 20, I remember

when he came running around the corner and he said, ‘‘Dad! Dad!’’

And, you know, ‘‘Mom, look at this great big CD.’’ It was a record.

I was kind of feeling like, ‘‘Wow, okay. Things have changed.’’ Now

he is 20 and the world is changing ever so fastly.

Mr. Misener, I want to ask you about your perspective where—

in the digital age, as we move forward and things become perhaps

all digital and move that direction, what happens when you die?

What happens when you want to pass that along? Should you own

that content? Are—should you have some certain privileges?

Should the government just stay out of this? Should every person

just make this—every organization make it up and have different

rules?

And then, I want to follow up and allow the MPAA to answer

this as well.

Mr. M

ISENER

. Thanks, Mr. Chaffetz.

You are talking, in part, about the First Sale doctrine and what

happens. And, as you know, for the most part digital downloads

and streaming are licenses that are granted to the users. At Ama-

zon, if you do die and your family has access to your account, yes,

you get access to that digital content as well. But that seems like

kind of an extreme way to circumvent the licensing rule.

So, hopefully this can be resolved in a way that is clear. And I

think we are happy to work with the Committee and also——

94

Mr. C

HAFFETZ

. But what do you think should happen?

Let me have the MPAA answer and then I will come back to you

for a second.

What should happen? Somebody gets an extensive library of mov-

ies, you know when they purchase a DVD it is pretty simple, right?

But, when they go out and they license all this, do they own it?

Do they not own it? Is it a combination? What is the right answer?

Mr. M

C

C

OSKEY

. I think it is a grey area today. And I will say

that with a flag that says I am an engineer not a lawyer. And—

but I do think, when you look at a product like the motion picture

industries put together like UltraViolet, one of the things that an-

ticipated is the need to share content across accounts. So that is

one way to deal with that is to allow multiple people actually to

have access to that content, you know, as long as they are——

Mr. C

HAFFETZ

. So, let us say I go out and I purchase a thousand

movies over the course of time, which seems like we have done in

our family. And I wanted to sell that. Are you okay if I sell that?

Mr. M

C

C

OSKEY

. Again, I am going to claim to be an engineer

here and not go down the legal path on that.

Mr. C

HAFFETZ

. And I guess for my colleagues on the Committee,

this is one of the questions is who owns that? And you are right

this is First Sale doctrine and how does that work in an electronic

age? So, does——

Mr. Sohn, did you—I see you nodding your head. Please, jump

on in here.

Mr. S

OHN

. Sure. No, I think you have put your finger on a really

important issue. The First Sale doctrine, as it currently exists in

law, seems to be mostly focused on tangible products. But certainly

consumers have some expectation that when they have engaged in

a transaction that looks like a purchase, that they ought to have

some rights to then dispose of that content down the line or share

it and so forth. And I think it is an important issue for the Sub-

committee to consider as it is reviewing copyright law is how can

we structure some approach to these issues that works for the dig-

ital age that recognizes both that, when people purchase things,

they do want to be able to pass them along. But, at the same time,

to recognize that there are a lot of new business models out there,

often people get things on a subscription basis, and it is less clear

that that is really an appropriate context in which First Sale

should apply. So——

Mr. C

HAFFETZ

. All right, so——

Mr. S

OHN

[continuing]. An appropriately cabined First Sale doc-

trine that applies to the digital age is, I think, something Congress

should work on.

Mr. C

HAFFETZ

. And I guess it is—and we will allow you, Mr.

Holst, to jump on in here—but that is one of the core questions.

We got the question somewhat surrounded. But I need help for you

all and others in the audience, what is the answer to these ques-

tions, not just restating the question.

But—Mr. Holst, please jump in here. I think my time is expiring.

So——

Mr. H

OLST

. I would just say that however you land on that—the

always to that question, transparency and consistency, is the most

95

important thing. If people know what is expected, most will comply.

So confusion is way worse than a slightly imperfect——

Mr. C

HAFFETZ

. So, if I said that you—when you buy it you own

it, you should be able to do what you want with it. Is that—would

everybody agree or disagree with that?

Mr. H

OLST

. I would say—briefly, I would say, if that was the

term at the point of sale, I would reflect that in my price and in

my model and I could be fine with it.

Mr. C

HAFFETZ

. And I actually like the way a lot of movies you

can get right now, you can rent it or you can buy it and purchase

it. But I think one of the questions for this Committee is how do

we deal with this in a broader context.

I will let you each quickly—but my time is expired, Chairman.

Mr. M

ISENER

. Well, we will work with you, obviously, Mr.

Chaffetz, and try to figure this out. It is not an easy question, it

goes to the core of copyrights. And it is—you know, we are—I think

you are seeing four people who understand the issue and don’t

have all the answers. But hopefully we will be able to work with

the Committee to come up with answers.

Mr. C

OBLE

. The gentleman’s time is expired.

Mr. C

HAFFETZ

. Thank you, Chairman.

Mr. C

OBLE

. And the—gentlemen you will have 5 days to respond

to whoever so we are okay time wise.

The distinguished gentleman from Louisiana?

Mr. R

ICHMOND

. Thank you, Mr. Chairman.

Let me just say, as I have been studying these issues, it has be-

come clear and I think that Mr. Chaffetz’s questions highlight the

complexity of what we are dealing with here. But also, I think that,

you know, as you all have testified, the importance of intellectual

property and copyright in the country is critically important that

we understand and that we get it right. Part of my fear is that we

will move so slow, as a deliberative body, that technology will pass

us by as we do that.

And sometimes, even as you all in your complex world negotiate,

we miss things. And the example I gave today at lunchtime was

ringtones. Friends in the music industry came and they said,

‘‘Cedric, I realize that I sold a million ringtones and I don’t have

any money from it.’’ It wasn’t covered in the contract because no-

body knew you would have ringtones that you could sell. And the

question became: who owned it and all of those. So, we have to

make sure we get it right. We have to make sure we understand

it.

But here is a question that I will pose to anybody out there is

that, what are the international implications of any changes we

consider to licensing models for digital delivery of content to the

consumer? And what are some of the things that we should con-

sider, as we talk about that, to make sure that the global consumer

has access to innovative U.S. products via efficient digital delivery

and so forth?

Anyone?

Mr. M

ISENER

. Mr. Richmond, I will take a stab at it. I think it

is probably a question best addressed by the rights holders, the

publishers, and maybe Mr. McCoskey will take a shot at it. But,

a lot of the content itself is geographically limited. That is to say

96

that distribution rights are cordoned off by the rights holders. And

so, from a technology platform that is global, we would love to see

much more trade in this area. But much of it is limited, again, by

the rights holders themselves.

Mr. M

C

C

OSKEY

. So, I think for our member companies, it is a big

part of their business. It is a huge amount of growth in the emerg-

ing worlds. And it is a place there—where there is a lot of interest

and consumption of American content.

I think, you know, we would certainly like to see, you know, a

few barriers to that and a few barriers to the movement of content

into those international markets. Now that it is all digital it is

pretty ubiquitous, from a distribution standpoint. So, it really

comes down to, you know, open markets and, you know, free mar-

kets with—around the world.

Mr. H

OLST

. I would say that the basic constructs of right and

wrong in ownership and fairness don’t know any international

boundaries. So, as a developer and as a vendor who works with lots

of developers, we care very much about these issues. But, in terms

of implementing and expressing those consistent perspectives that

is, I am afraid, beyond the scope—that is an international issue,

which I am no expert in. But, the rules should be—the basic rules

are the same.

Mr. S

OHN

. And I would just add, there is—there are trade trea-

ties around these topics that provide for some basic principles of in-

tellectual property internationally. I do think that the basic dy-

namic is true on a global level the same as it is on a domestic one,

which is: it is crucially important that we find ways to license con-

tent and distribute content in attractive lawful ways around the

world. Because certainly, if content isn’t available in those other

markets, it is going to fuel piracy in those markets and it is going

to fuel sort of the dark side of the market. And we want the lawful

market growing.

Mr. R

ICHMOND

. And in—as I close, and you all can submit this

in writing or just any ideas that you have that we should keep in

mind as we ensure or at least I try to ensure that we look at this

from a very balanced approach when we start talking about new

content delivery. We are talking about a new consumption econ-

omy. But, we also have to make sure that we are still driving inno-

vation and making sure we continue the economic growth. So, any-

thing you have and any thoughts I would certainly appreciate. And

my office is always open for you all to drop by and have these con-

versations.

With that, Mr. Chairman, I yield back.

Mr. C

OBLE

. I thank the gentleman.

The gentleman from Texas.

Mr. F

ARENTHOLD

. Thank you very much, Mr. Chairman.

And I want to revisit the digital First Sale doctrine for a second.

You know, back in the old days, when you had a book and you

bought it, the copyright holder got paid and then it was your book

to sell. And, of course, when you sold it you didn’t have it anymore.

And that is kind of the problem now in the digital age. You can

make a near perfect or perfect copy of something and then sell your

original. There is no real technological way to deal with that. Any

sort of DRM, digital rights management, you put in get taken

97

away. Do you all see a solution? Or are we really—are looking at

something that is dead, from a—digital First Sale is dead, from a

practical standpoint.

I will start with Mr. Misener?

Mr. M

ISENER

. Thanks, Mr. Farenthold. I think that we have